-

From the Wilson Center

Africa on the Move: The Role of Political Will and Commitment in Improving Access to Family Planning

Excerpted below is the adapted abstract, by lead authors Eliya Msiyaphazi Zulu and Violet Murunga. The full report is available for download from the Wilson Center’s Africa Program.MORE

Despite commitments to the program of action for the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development and Millennium Development Goal 5 (focused on maternal and reproductive health), little progress has been made in improving access to family planning and slowing rapid population growth in Africa. Lack of political will has been highlighted among the key factors behind the lackluster performance in addressing these sensitive development issues. However, the situation is changing with some African governments embracing family planning as a key tool for improving child and maternal health, slowing population growth, preserving the environment, and enhancing broader efforts to alleviate poverty.

This study examines factors that have propelled the change in attitudes of some political leaders to champion family planning, assesses how such political will has manifested in different contexts, and explores how political will affects the policy and program environment. Mixed policy analysis methods were employed, including desk review of policy and program documents and stakeholder interviews conducted in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda – three countries that have made phenomenal progress in increasing contraceptive use in the recent past.

Lessons from this study will help galvanize efforts to improve access to reproductive health services in countries where little progress is being made. The results provide useful insights on the dawn of a new Africa where strategic political leadership is playing an increasingly valuable role in overcoming the continent’s longstanding development shackles. The study shows that political will is mainly changing due to increased availability of evidence showing that high population growth undermines efforts to alleviate poverty and hunger as well as investments in the quality human capital that least development countries desperately need in order to transform their economies.

The high sensitivity about childbearing and suspicions regarding the intentions of western development partners in promoting family planning in order to slow population growth are dissipating as more Africans are opting to have fewer children and demanding family planning. This study points to the need for global development partners to be much more cognizant of the drivers of Africa’s emerging success and focus their development assistance on enhancing, nurturing, and highlighting local leadership traits, capacities, and systems that are producing positive results, as well as support governments that have embraced family planning to ensure that no woman has an unwanted pregnancy due to lack of family planning.

Download the full report from the Wilson Center. -

Beat on the Ground

PHE and Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change: Stronger Together

MOREOver the past several years, community-based adaptation has emerged alongside national and regional climate change initiatives as a strategic, localized approach to building resilience and adaptive capacity in areas vulnerable to climate change.

-

For Yemen’s Future, Global Humanitarian Response Is Vital

June 12, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffMOREThe original version of this article, by Nancy Lindborg, appeared on The Huffington Post.

This weekend in Sana’a, I had dinner with a group of young men and women activists who are on the forefront of Yemen’s historic struggle for a better future. They turned out for change with great courage last year, and at dinner, with great eloquence they outlined for me the many challenges facing Yemen during this critical transition period: conflict in the north and south, weak government institutions, cultural barriers to greater women’s participation, an upended economy, and one of the world’s highest birthrates. And, as one man noted, it is difficult to engage the 70 percent of Yemeni people who live in rural areas in dialogue about the future when they are struggling just to find the basics of life: food, health, water.

His comment makes plain the rising, complex humanitarian crisis facing Yemen. At a time of historic political transition, nearly half of Yemen’s population is without enough to eat, and nearly one million children under the age of five are malnourished, putting them at greater risk of illness and disease. One in 10 Yemeni children do not live to the age of five. One in 10. This is a staggering and often untold part of the Yemen story: a story of chronic nationwide poverty that has deepened into crisis under the strain of continuing conflict and instability.

Unfortunately, in communities used to living on the edge, serious malnutrition is often not even recognized in children until they are so acutely ill that they need hospitalization.

Continue reading on The Huffington Post.

Nancy Lindborg is the assistant administrator of the Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance at the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Sources: U.S. Department of State.

Photo Credit: Informal settlements near the Haddjah governorate, courtesy of E.U. Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection.Topics: demography, environmental health, food security, foreign policy, gender, global health, humanitarian, nutrition, population, poverty, sanitation, security, USAID, water, Yemen, youth -

The Year Ahead in Political Demography: Top Issues to Watch

June 8, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy MadsenMORE2011 and the first half of 2012 have been a remarkable period for political demography, with theories about the relationships between age structure and governance validated in real time by the events of the Arab Spring. Although such game-changers are rarely predictable, the year ahead promises to be eventful as well, with new demographic research and major policy initiatives on the horizon. Below are brief assessments of some of the top issues to watch between now and next summer.

1. The Evolving Story of the Arab Spring

The Arab Spring was anticipated by few observers, but for a handful of political demographers it was a watershed of sorts. As readers of this blog know, political demography research shows that countries with very young age structures are prone both to higher incidence of civil conflict and – most relevant to the outcomes of the Arab Spring – to undemocratic governance. This nuance escaped many observers of the region’s drama. Violence and conflict erupted not from raging citizens in the streets but from military and militia forces unleashed by autocrats unwilling to cede their grip on power. Young people, and their fellow protestors of all ages, were acting as a force for positive change in their demonstrations against corrupt and unrepresentative leadership. The difference in outcomes across the region, according to Richard Cincotta, can be attributed to the fact that as age structures mature, elites become less willing to trade their political freedoms to autocratic leaders in exchange for the promise of security and stability.

When considered with this important distinction in mind, the initial events following the uprising in Tunisia that quickly spread across the region played out in a neatly linear fashion. Among the five countries where revolt took root, those with the earliest success in ousting autocratic leaders also had the most mature age structures and the least youthful populations.

In Tunisia, with a median population age of 29, one month passed between a fruit seller’s self-immolation and Zine El Abedine Ben Ali’s flight to exile. In Egypt and Libya, where median age is close to 25 years (identified by Cincotta as a threshold when countries are at least 50 percent likely to be democratic), Hosni Mubarak and Moammar Gaddafi took three weeks and eight months, respectively, to lose their titles. Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen (median age 17), took one year to be convinced to formally resign, while in Syria (median age 21), the 15-month uprising continues to be brutally repressed by Bashar Assad’s forces.

Of course, overthrowing a dictator, while inspiring and liberating to those whose rights have been repressed, is only the first step in achieving democracy. In the coming year, the countries that have already taken steps toward solidifying regime change will face continued tests as internal tensions surface. Even in Tunisia, recent clashes signal that political divisions and economic uncertainty have not been resolved. With potentially divisive elections ahead in Egypt and Libya, a holdover from the Saleh regime leading Yemen, and Syria’s fate unknown, the coming year should offer political demographers further evidence of the soundness of the age structure and democracy thesis.

2. New Commitments to Family Planning

Reproductive health and demography go hand-in-hand, and two milestones for family planning advocates are fast approaching: the 20th anniversary of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, and the 2015 endpoint of the Millennium Development Goals.

These historic commitments by governments will be joined by a major initiative to generate new funding and political will this summer at an international family planning summit in London on July 11. The summit will be co-hosted by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Melinda made an impassioned TEDxChange speech in support of the issue in April), and the UK’s Department for International Development, for whom family planning is a priority in efforts to reduce maternal and child mortality.

Details of the summit have yet to be finalized and publicly released, but financial commitments from donors and developing countries are anticipated toward meeting a new and ambitious goal of generating $4 billion to fund contraceptives for 120 million women in developing countries by 2020. Assuming these are new users, rather than those who would be expected by projecting recent growth in contraceptive use forward, this would represent more than half of the estimated 215 million women with an unmet need for family planning.

Why does new family planning funding matter for political demography? Rates of contraceptive use are lowest and fertility highest in countries with youthful age structures. Such population dynamics exacerbate the challenges governments face in providing education, health, and basic infrastructure services, as well as supporting an economic climate conducive to industry diversification and job creation. In turn, the likelihood of civil conflict and undemocratic governance is higher in such countries.

While policies that recognize the benefits of family planning may be solid, funding and implementation often fall woefully short. In the least developed countries, less than one-third of reproductive-age women are using any contraception, and the rate has grown by just 0.4 percentage points annually over the past decade. Meanwhile, funding from all sources is less than half the amount required to meet unmet need. If the July summit motivates a new groundswell of financial support, 2012 could incite major strides toward improvements in individual health and well-being as well as demographic momentum in the remaining high-fertility countries.

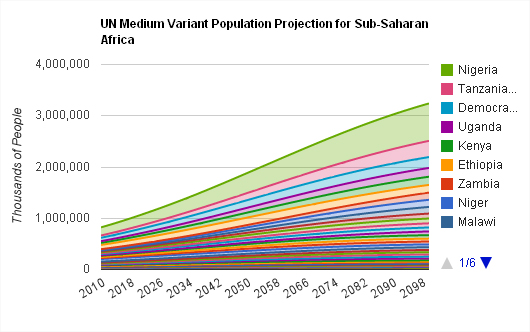

3. Demographic Diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa

The current era of global demographic diversity has been distinguished by both record-low fertility rates in parts of Europe and eastern Asia and persistently high fertility across most of western, central, and eastern Africa. More than one-quarter of women in sub-Saharan Africa would like to postpone or avoid pregnancy, but are not using contraception, demonstrating a large unmet need for family planning.

The U.S. government-funded Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program is the largest single source for detailed data on health status and behavior in high-fertility developing countries, and in turn informs estimates and projections of demographic trends. Recently, DHS reports have been released showing that contraceptive use over the past five years is growing much faster than the regional average in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda. In turn, fertility rates have dropped, ranging from a relatively modest 0.3 children per woman in Malawi and an unprecedented 1.5 children per woman in Rwanda.

These findings suggest that the pattern of demographic stagnation in sub-Saharan Africa may be shifting, perhaps due to governments’ and donors’ investments in family planning. However, newer survey results for Mozambique, Uganda, and Zimbabwe present a more mixed picture, with modest gains in contraceptive use in Uganda, offset by declines in the other two countries.

Click here for the interactive version (non-Internet Explorer users only).

Additional recent survey results show that use of modern contraceptive methods has barely increased in Senegal (from 10 percent in 2005 to 12 percent in 2010-11). And while modern contraceptive use increased in the Republic of Congo from 13 percent in 2005 to 20 percent currently, fertility also rose slightly, from 4.8 to 5.1 children per woman.

Approximately 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa are slated for DHS fieldwork this year, including one of the continent’s giants, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and several of the highest-fertility countries in the region. (Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, the demographic heavyweights in this year’s group of DHS reports are Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Pakistan.)

The upcoming surveys will provide greater clarity about whether the promising signs of family planning adoption and the potential for progress through the demographic transition in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda are initiating widespread change across the continent, or whether the need for commitments such as those generated by the London summit is even stronger.

4. New Population Projections

DHS reports are critical inputs for the world’s most comprehensive and readily accessible set of demographic data, the UN Population Division’s World Population Prospects. This database is fully updated and revised biannually, in large part due to the steady stream of newly available estimates from the DHS and related sources, such as national censuses. The next revision of World Population Prospects, based on estimates for mid-year 2012, is expected to be published in spring 2013.

The previous revision of World Population Prospects was notable for its methodological overhaul. In addition to extending the projections until 2100, the Population Division shifted to a probabilistic technique (as opposed to assuming convergence at a single fertility rate of 1.85 children per woman) that generates 100,000 possible fertility trajectories for each country and selects the median as the medium fertility variant, commonly cited as the most likely projection. Still, the basic parameters remain the same: With fertility rates the strongest driver of population projections, low, medium, and high fertility variants are constructed around the assumption that countries will converge towards replacement level fertility, around 2.1 children per woman.

In some cases, this results in projections that are vastly at odds with recent trends. For example, in Japan, fertility has fallen by 38 percent, from replacement level in the early 1970s to 1.3 children per woman in 2010, but the UN projects it to immediately reverse course and begin rising to 1.8 by mid-century. If the projection holds, Japan’s population will decline relatively modestly, from 127 million to 109 million. But if fertility stays constant at current levels, the population will fall below 100 million. For low-fertility countries like Japan, all UN scenarios assume constant or rebounding fertility rates, even though continued decline may be a plausible outcome in some cases.

When next year’s projections are released, a cluster of media articles will report the projected world population for 2050. In last year’s revision, the medium fertility variant resulted in a projection of 9.3 billion, an increase from the 9.1 billion projected two years earlier based on higher projected fertility in the future. Such reports often overlook the range of population totals possible depending on fertility paths: If the global fertility rate varies by 0.5 children per woman in either direction, the total population could be more than one billion higher or lower in 2050, with an even wider range possible by 2100.

Most of the projected growth in world population, and its potential range, will be driven by the high-fertility countries concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. Population projections for these countries vary tremendously based on fertility scenarios informed by the recent DHS results described above.

In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, fertility has fallen over the past 40 years, but by a gradual 15 percent. The UN projects it to drop more than twice as fast, by more than two children per woman (39 percent), in the next four decades. In any scenario, Nigeria is on track for rapid population growth, but the potential range based on fertility outcomes is wide. If fertility declines as projected in the medium variant, the country would grow from 158 million to 390 million. And although unlikely, the constant fertility projection of 504 million Nigerians in 2050 should be kept in mind given the slow pace of fertility decline to date.

Population projections are highly wonky, but their careful production and regular revision are essential for accurate planning of economic and social needs in countries around the world. While governments with dedicated census agencies, such as those in the U.S., Japan, or India, rely on internally-generated estimates, the UN projections serve as the primary indication of population trends in countries with spottier data coverage and have tremendous utility in gauging future needs for infrastructure, housing, health care across the life cycle, education, jobs, and other investments.

By no means is this an exhaustive list of factors that will affect political demography research and policy over the coming year. Other events to watch for include the Rio+20 conference on sustainable development in June, where the priority issues of jobs, energy, infrastructure, and resources will be shaped by demographic trends, and continued attention to prospects for the demographic dividend in Africa. Political demography is inherently cross-disciplinary, and the field’s researchers and practitioners will be engaged on multiple fronts in the year ahead.

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and senior technical advisor at Futures Group.

Sources: Al Jazeera, Bongaarts (2008), Cincotta (2008), Cincotta (2012), Cincotta and Leahy (2006), Grist, Guttmacher Institute, MEASURE DHS, The New York Times, NPR, Population Reference Bureau, UN Population Division, The Washington Post.

Image Credit: “The Face of a Tyrant,” courtesy of flickr user freestylee (Michael Thompson); video courtesy of TED; chart created by Schuyler Null, data from UN Population Division.Topics: Africa, democracy and governance, demography, development, Egypt, family planning, foreign policy, global health, Japan, Libya, Middle East, population, security, Syria, Tunisia, UN, video, Yemen, youth -

Bringing Environment and Climate to the 2012 Population Association of America Annual Meeting

June 5, 2012 // By Sandeep BathalaMOREOver 2,100 participants attended the 2012 Population Association of America (PAA) annual meeting in San Francisco this May. PAA was established in 1930 to research issues related to human population. This year, for the first time, the meeting featured a notable contingent of demographers, sociologists, and public health professionals working on environmental connections.

I followed as many of the environment-population discussions on newly published or prospective research papers as possible (about 20 in total). I found four papers particularly noteworthy for the connections made to women, family planning, and climate change adaptation.

Samuel Codjoe of the University of Ghana spoke about adaptation to climate extremes in the Afram Plains during one of the population, health, and environment (PHE) panels organized by Population Action International. Although developed nations are historically the major contributors of greenhouse gases due to comparatively high levels of consumptions, developing countries are the most vulnerable to the consequences of climate change – in part because of continued population growth. As a result, adaptation strategies in countries like Ghana are particularly important; and given women’s often-outsized role in water and natural resource issues, a focus on gender-specific adaptation even more so.

Codjoe presented an analysis of preferred adaptation strategies to flood and drought, broken down by gender and three common occupations – farming, fishing, and charcoal production). He said he hopes his assessment – part of a collaborative research effort with Lucy K.A. Adzoyi-Atidoh of Lincoln University – will aid in the selection and implementation of successful adaptation options for communities and households in the future.

“Understanding differences in the priorities that women place on adaptation may prove to be important in the effectiveness of climate change adaptation – and the sustainability of communities,” he said.

David López-Carr of the University of California, Santa Barbara, speaking on behalf of a group of researchers with World Wildlife Fund, teased out the gender dynamic further when he presented on ways to help the conservation sector determine next steps for existing PHE projects. Practitioners from seven of the eight PHE projects currently implemented by conservation organizations (defined by having been involved for at least three years in bringing family planning to local communities) recently said the links to women’s empowerment were among the most important aspects of successful projects.

López-Carr therefore emphasized the need for additional research on how PHE projects can support and empower women, both economically and socially. He also noted, like Codjoe, the potential impact women often have on the management of their community’s natural resources, saying this was another area where research on the empowering effect of PHE programs can provide further backing for integrated programs.

Karen Hardee of Futures Group spoke about how the experiences of integrated PHE projects, despite most not being designed to respond to climate change specifically, have lessons to offer climate change efforts. Her work was done in partnership with the Population Reference Bureau, Population Action International, and U.S. Agency for International Development. She concluded that community-based adaptation approaches should consider population dynamics in vulnerability assessments. Meeting unmet need for family planning, she said, can assist communities adapting to climate change by building resilience. And as result, “PHE approaches should be able to qualify for funding under community-based adaptation programs.”

Shah Md. Atiqul Haq of the City University of Hong Kong presented research he conducted in Bangladesh that found that women tended to feel that a large family size was not advantageous during floods. This, he said, was indicative of their increased understanding of vulnerability and an endorsement of providing knowledge and access to family planning services as part of climate change adaptation strategies.

The inclusion of more environment, and particularly PHE, related presentations at this year’s conference was good to see – perhaps a sign that demography is becoming a more complex and comprehensive field, with a focus more on population structure and its interactions with other issues, rather than a singular fascination with growth.

In particular, panelists showed that the nexus between demography, gender equity, and climate change continues to grow in importance, both in the research and practitioner communities.

Photo Credit: Tribal women and children in Kerala state, India, courtesy of flickr user Eileen Delhi. -

Guest Contributor

Philippines’ Bohol Island Demonstrates Benefits of Integrated Conservation and Health Development

MORE

In March 2012, I participated in a study tour to the island of Bohol, near the unique Danajon double barrier reef ecosystem – the only one of its kind in the Philippines and one of only three in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Nowhere is the connection between population dynamics and biodiversity more evident than in the Philippines, one of the most densely-populated countries on the planet, with more than 300 people per square kilometer. Nearly every major species of fish in the region shows signs of overfishing, according to the World Bank.

-

Dot-Mom

Adenike Esiet: Building Support for Improving Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Nigeria

MORE“In Nigeria, young people under the age of 25 are driving the HIV epidemic…and that’s been the opening place for people to begin to say, ‘let’s address the issues of young people’s sexual and reproductive health,’” said Adenike Esiet, executive director of Action Health Incorporated in Lagos, during an interview with ECSP.

On any number of health indicators, girls suffer disproportionately. “For every one boy in the age bracket of 10 to 24 who is HIV positive, there are three girls who are HIV positive,” Esiet said. “Over 60 percent of cases of complications from unsafe abortion reported in Nigerian hospitals are amongst adolescent girls. In fact in literature, 10-15 years ago, this was described as ‘a schoolgirl’s problem’…and it’s still an ongoing problem.” She added: “And for girls too, the issue of sexual violence is huge. It goes largely unreported but it’s occurring at epidemic levels.”

Esiet spoke on an adolescent health panel during the April 25 “Nigeria Beyond the Headlines” event at the Wilson Center. Progress is slow on these issues, in large part because “there’s a whole lot of silence about acknowledging young people’s sexuality,” she said.

Adults “want to believe [adolescents] shouldn’t be sexually active.” But turning a blind eye to adolescent sexuality can mean that efforts “to provide access to education or services is hugely resisted by practitioners who should be doing this.”

Action Health works to fill the gap that emerges. “Our work covers advocacy, community outreach, and service provision for young people,” said Esiet.

“Our primary entry road in to work with young people is creating access to sexuality education and youth friendly services. And in the course of trying to do that, we have to do a whole lot of advocacy with government and also with ministries or education and ministries of health and youth development.”

The group has worked with government officials and agencies to establish a nationwide HIV education curriculum and paired with local healthcare providers to increase access to “youth-friendly” sexual and reproductive health services. Funding shortages and insufficient resources have hampered the curriculum’s success, though, and the pervasive attitude against youth sexuality has limited the reach of services, she said. Ultimately, “there are a whole range of issues that truly need to be addressed” for outreach efforts to be successful.

-

Population-Climate Dynamics: From Planet Under Pressure to Rio

May 11, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Roger-Mark De Souza, appeared on the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN).MORE

In late May, I presented research on population and climate dynamics in hotspots at the Planet Under Pressure conference in London, in a session organized by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network. As we prepare for the Rio+20 Earth Summit in June, I reflect on the roles of population dynamics and climate-compatible development for ensuring a future where we can increase the resilience of the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.- Improving our well-being and the future we can have is within our reach: We can take action to improve well-being through specific actions that can produce short term results. This is a key message encapsulated in the concept of climate-compatible development, reflected in many presentations and discussions that I heard at Planet Under Pressure. Even though others were not calling it “climate-compatible development,” the essence and the meaning behind the research was the same – small concrete discrete steps are possible, and taking action on population dynamics is one of them.

- Population is on the agenda: Population issues – growth, density, distribution, aging, gender – were a constant at Planet Under Pressure – and in more ways than just looking at population as a driver. It is clear that there is interest, and a need, to address population as a key component of climate-compatible development.

- But those concerns and issues must be location specific, and must be contextualized for the policy and programmatic environment: Population issues must be framed in the appropriate context – and must move beyond academic exploration. I attended one session where a paper presented an academic supposition of whether we should invest in consumption versus fertility reduction to produce short-term returns for climate, but the analysis was completely devoid of any political, policy, or programmatic truth-testing. We must factor in those considerations when making recommendations, if ultimately we are really looking to make the difference that we can.

Photo Credit: “Urbanization in Asia,” courtesy of United Nations Photo.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.