-

Book Preview: ‘Environmental Politics: Scale and Power’

February 1, 2011 // By Shannon O’LearThe cover of my book, Environmental Politics: Scale and Power, shows two cows casually rummaging through piles of garbage on the streets of a city somewhere in India. It’s a colorful, but disturbing, image. Why not show cows in their “natural” setting, say, in a Kansas pasture? Who let them into the street? Why are they eating garbage? The image is symbolic of what the book aims to achieve: to get us out of our comfort zones in thinking about environmental issues and challenge us to reconsider how we think about issues like climate change, energy, food security, garbage, toxins, and resource conflicts.MORE

The book draws from my experience teaching environmental policy, environmental geopolitics, international conflict, and human geography. It starts by asking some fundamental questions: What exactly is “the environment” anyway? Is there any part of the world that is completely untouched by human actions? How do different forms of power selectively shape our understanding of particular environmental issues (while obscuring other issues from our view)?

The book draws on the idea of the “Anthropocene” – a new geologic era characterized by irreversible, human-induced changes to the planet. Because these changes (which in large part have already occurred) are irreversible, Anthropocene-subscribers argue we should focus our efforts on mitigation, adaptation, and coming to terms with the realities of the environment as it is, rather than something that must be returned to some previous or “normal” state.

Our understanding of environmental issues is shaped by various types of power – economic, political, ideological, and military – and therefore tends to be limited in terms of spatial scale. Why do we tend to think of climate change as a global phenomenon instead of something we might experience (and contend with) locally? Is food security something we should be mindful of when we make individual choices about food? We tend not to discuss what happens to our garbage, but everyone knows about recycling, right?

Environmental Politics: Scale and Power offers non-geographers an appreciation of how and why geographers think spatially to solve problems. Commonly accepted views of environmental issues tend to get trapped at particular spatial scales, creating a few dominant narratives. When we combine a spatial perspective with an inquiry into the dynamics of power that have influenced our understanding of environmental issues, we can more clearly appreciate the complexity of human-environment relations and come to terms with adapting to and living in the Anthropocene era.

Today’s environmental challenges can sometimes appear distant and immense, but this book aims to show how decisions we make in our day-to-day lives – from buying bottled water and microwave popcorn to diamond jewelry – have already had an effect on a grand scale.

Shannon O’Lear is a professor of geography at the University of Kansas and the author of Environmental Politics: Scale and Power. She has recently completed a research project examining why we do not see widespread or sustained environmental resource-related conflict in Azerbaijan, as literature on resource conflict would suggest.

Image Credit: Environmental Politics: Scale and Power, courtesy of Justin Riley and Cambridge University Press. -

Guest Contributor

Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty?

MOREThe much-anticipated Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review(QDDR) demands to be taken seriously. Its hefty 250 pages present a major rethink of both American development policy and American diplomacy. Much of it is to be commended:

-

Watch: Joan Castro on Resource Management and Family Planning in the Philippines

January 27, 2011 // By Wilson Center Staff“Sixty-percent of Filipinos live in the coastal areas,” said Joan Castro, executive vice president of PATH Foundation Philippines, Inc., in an interview with ECSP, and dwindling fish stocks are an issue across the archipelago. “With increasing population, the food that goes on the table for a lot of families in these coastal communities was an issue, so food security was the theme of the IPOPCORM project.”MORE

IPOPCORM (standing for “integrated population and coastal resource management”) was started in 2000 and ran for six years. It sought to address population, health, and the environment (PHE) issues together in rural, coastal areas of the Philippines.

“When we started IPOPCORM, there was really nothing about integrating population, health, and environment,” Castro said. IPOPCORM provided some of the first evidenced-based results showing there is value added to implementing coastal resource management and family planning in tandem rather than separately.

The PATH Foundation worked with local governments and NGOs to establish a community-based family planning system while also strengthening local resource management. The results showed a decrease in unmet need for family planning and also improved income among youth in the remote areas they worked in.

Today, Castro also serves as the PHE technical assistance lead of the Building Actors and Leaders for Advancing Community Excellence in Development (BALANCED) project – a USAID initiative transferring PHE know-how to regions of East Africa and Asia. -

China’s Biggest Environmental Stories of 2010/11

January 21, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffMORE The original version of this post first appeared on ChinaDialogue’s The Daily Planet blog, December 23, 2010.

The original version of this post first appeared on ChinaDialogue’s The Daily Planet blog, December 23, 2010.

Last month I spent a few days in Washington, DC meeting mostly with people working on U.S.-China environmental relations. Among others, I met with Jennifer Turner, director of the China Environment Forum at the Wilson Center (and my former boss), and we had an exciting conversation about the biggest China environmental stories covered in the United States in 2010, and what we hope to see in 2011. I was inspired to write this post based on our conversation. This is of course neither definitive nor exhaustive, but merely my perspective on how things look from Washington.China Is Winning the Clean Energy Race. Energy was the big story in 2010. Studies show that the United States will need to renovate or retire virtually all of its power plants by 2050, and China must build a modern energy sector to serve a growing population. Both countries emphasized their intentions to build a clean energy economy in 2010 and almost immediately competition was dubbed a “race.” Soon after it was declared a two-party race, it became evident that China was winning.

China’s clean energy investment is two times greater than that of the United States, according to a Pew Charitable Trust report published last year. The news has centered upon China’s ability to make sweeping changes to domestic energy markets, in stark contrast to the United States’ inability to pass climate legislation. Most notably in 2010, China passed a regulation requiring that a percentage of all electric company profits be used for energy efficiency every year.

Energy “Co-op-etion.” Perhaps as a response to fears of “losing” the energy race, public opinion in the United States focused on new and existing energy cooperation and on market fairness. The U.S.-China Clean Energy Research Center, signed in 2009, was officially launched in 2010 and is likely to formalize a great deal of on-going cooperation on energy between the United States and China. In December, Jonathan Silver, Executive Director of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program, spoke at a conference in San Francisco and described the developing energy relationship between China and the United States as “co-op-etition” – the two countries have complementary markets and a lot to learn from each other but will compete in U.S., Chinese, and international markets to sell clean technologies.

Concerns about the fairness of the market – initially because of changes in China’s government procurement laws discriminating against foreign clean technology companies – peaked with the U.S. Steel Workers’ petition in October. Americans are concerned that their technologies will suffer in the international market because of Chinese clean technology subsidies.

China “Ruined” Copenhagen. Perception that China ruined Copenhagen dominated the U.S. news early in the year but was softened by a more positive outlook following Cancun. Anxiety in Washington, DC regarding the accuracy of China’s CO2 data colored many debates on American participation in international climate negotiations all year.

Oil and Rare Earths. The oil spill in Dalian in July made big news in the United States as it came in the wake of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Many comparisons were made, despite the enormous difference in scale between the two incidents. Rare earth elements (the spine of the clean technology industry) were another major concern that arose in 2010 in Washington. Many of America’s rare earth mines were shuttered decades ago when Chinese mines were able to produce more affordably. This year, China began restricting rare earth exports, at least partially for environmental reasons, forcing the United States to consider reopening many of its mines and how to deal domestically with the environmental effects of those mines.

In 2011 I hope that interest in China’s environment will continue in the United States, but I expect that we will see less on renewables, as stimulus money runs thin, and rising concern for more traditional pollutants and basic environmental governance in China (especially regarding water and air pollutants).

The 12th Five-Year Plan. Set to be released early 2011, the 12 Five-Year Plan will initially dominate energy stories as it outlines how China will meet its ambitious energy intensity targets. I expect nuclear energy will replace wind and solar as the big stories in 2011. Nuclear liability should be addressed in China in 2011, as it was in India in 2010. Because of the close energy business ties between China and the United States, liability laws in China are likely to be more sympathetic to the needs of American companies than India’s recent law, which exposes nuclear components suppliers to unlimited liability.

Soil Pollution Prevention and Remediation. China’s soil pollution survey was completed in 2009 and the draft Provisional Rules on Environmental Management of the Soil of Contaminated Sites was released by the Ministry of Environmental Protection for comment in December 2009. The problem is huge and significant in China’s development and construction boom, and little data has been publicly released from the survey. I expect that in 2011, we will start to see active management and enforcement, at least in major cities.

Water Quality and Quantity. Water has and will likely continue to be, the greatest environmental concern in China and abroad, given its transboundary nature. Turner suggests we will see more on control of and attention to nitrogen pollution in China’s waterways in 2011.

To chime in with your comments on what you feel were the biggest stories of 2010 and what you predict will dominate 2011, be sure to let us know below or on ChinaDialogue.

Linden Ellis is the U.S. project director of ChinaDialogue and a former project assistant for the Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum.

Sources: Asia Society, ChinaDialogue, The New York Times, Pew Charitable Trust.

Photo Credit: “Factory in Inner Mongolia,” courtesy of flickr user Bert van Dijk. -

Friday Podcasts

Elizabeth Malone on Climate Change and Glacial Melt in High Asia

MORE “There’s nothing more iconic, I think, about the climate change issue than glaciers,” says Elizabeth Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Malone served as the technical lead on “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerability to Glacier Melt Impacts,” a USAID report released in late 2010 that explores the linkages between climate change, demographic change, and glacier melt in the Himalayas and other nearby mountain systems.

“There’s nothing more iconic, I think, about the climate change issue than glaciers,” says Elizabeth Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Malone served as the technical lead on “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerability to Glacier Melt Impacts,” a USAID report released in late 2010 that explores the linkages between climate change, demographic change, and glacier melt in the Himalayas and other nearby mountain systems.

Describing glaciers as “transboundary in the largest sense,” Malone points out that meltwater from High Asian glaciers feeds many of the region’s largest rivers, including the Indus, Ganges, Tsangpo-Brahmaputra, and Mekong. While glacial melt does not necessarily constitute a large percentage of those rivers’ downstream flow volume, concern persists that continued rapid glacial melt induced by climate change could eventually impact water availability and food security in densely populated areas of South and East Asia.

Rapid demographic change has potentially factored into accelerated glacial melt, even though the connection may not be a direct one, Malone adds.

Atmospheric pollution generated by growing populations contributes to global warming, while black carbon emissions from cooking and home heating can eventually settle on glacial ice fields, accelerating melt rates. Given such cause-and-effect relationships, Malone says that rapid population growth and the continued retreat of High Asian glaciers are “two problems that seem distant,” yet “are indeed very related.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

On the Beat

National Geographic’s Population Seven Billion

The short feature above and accompanying cover article in the January 2011 issue launch National Geographic’s seven-part year-long series examining global population. The world is set to hit seven billion this year, according to current UN projections, and may reach nine billion by 2045.MORE

The authors point out that today, 13 percent of people don’t have access to clean water globally and 38 percent lack adequate sanitation. Nearly one billion people have inadequate nutrition. Natural resources are strained. Is reducing population growth the key to addressing these problems?

Not according to Robert Kuznig, author of National Geographic’s lead article, who writes that “fixating on population numbers is not the best way to confront the future…the problem that needs solving is poverty and lack of infrastructure, not overpopulation.”

“The most aggressive population control program imaginable will not save Bangladesh from sea-level rise, Rwanda from another genocide, or all of us from our enormous environmental problems,” writes Kuznig. Speaking on NPR’s Talk of the Nation last week, he reiterated this message, saying global problems “have to be tackled whether we’re eight billion people on Earth, or seven, or nine, and the scale for them is large in any case.”

Instead, the challenge is simultaneously addressing poverty, health, and education while reducing our environmental impact, says Kuznig.

“You don’t have to impose prescriptive policies for population growth, but basically if you can help people develop a nice, comfortable lifestyle and give them the access to medical care and so on, they can do it themselves,” said Richard Harris, a science correspondent for NPR, speaking with Kuznig on Talk of the Nation.

Kuznig’s article highlights the Indian state of Kerala, where thanks to state investments in health and education, 90 percent of women in the state can read (the highest rate in India) and the fertility rate has dropped to 1.7 births per woman. One reason for this is that educated girls have children later and are more open to and aware of contraceptive options.

Whither Family Planning?

In a post on Kuznig’s piece, Andrew Revkin, of The New York Times’ Dot Earth blog, points to The New Security Beat’s recent interview with Joel E. Cohen about the crucial role of education in reducing the impact of population growth. Cohen asks: “Is it too many people or is it too few people? The truth is, both are real problems, and the fortunate thing is that we have enough information to do much better in addressing both of those problems than we are doing – we may not have silver bullets, but we’re not using the knowledge we have.”

Although the National Geographic article and video emphasize the connections between poverty reduction, health, education, and population growth, both give short shrift to family planning. It’s true that fertility is shrinking in many places, and global average fertility will likely reach replacement levels by 2030, but parts of the world – like essentially all of sub-Saharan Africa for example – still have very high rates of fertility (over five) and a high unmet demand for family planning. Globally, it is estimated that 215 million women in developing countries want to avoid pregnancy but are not using effective contraception.

Development should help reduce these levels in time, but without continued funding for reproductive health services and family planning supplies, the declining trends that Kurznig cites, which are based on some potentially problematic assumptions, are unlikely to continue.

As Kuznig told NPR, “you need birth-control methods to be available, and you need the people to have the mindset that allows them to want to use them.”

At ECSP’s “Dialogue on Managing the Planet” session yesterday at the Wilson Center, National Geographic Executive Editor Dennis Dimick urged the audience to “stay tuned – you can’t comprehensively address an issue as global and as huge as this in one article, and within this series later in the year we will talk about [family planning] very specifically.” Needless to say, I look forward to seeing it, as addressing the unmet need for family planning is a crucial part of any comprehensive effort to reduce population growth and improve environmental, social, and health outcomes.

Sources: Center for Global Development, Dot Earth, NPR, Population Reference Bureau, World Bank.

Video Credit: “7 Billion, National Geographic Magazine,” courtesy of National Geographic.Topics: climate change, demography, development, environment, family planning, On the Beat, population, poverty, video -

Turning Up the Water Pressure [Part One]

January 18, 2011 // By Russell SticklorMOREThis article by Russell Sticklor appeared originally in the Fall 2010 issue of the Izaak Walton League’s Outdoor America magazine.

For many Americans, India — home to more than 1.1 billion people — seems like a world away. Its staggering population growth in recent years might earn an occasional newspaper headline, but otherwise, the massive demographic shift taking place on our planet is out of sight, out of mind. Yet within 20 years, India is expected to eclipse China as the world’s most populous nation; by mid-century, it may be home to 1.6 billion people.

So what?

In a world that is increasingly connected by the forces of cultural, economic, and environmental globalization, the future of the United States is intertwined with that of India. Much of this shared fate stems from global resource scarcity. New population-driven demands for food and energy production will increase pressure on the world’s power-generating and agricultural capabilities. But for a crowded India, domestic scarcity of one key resource could destabilize the country in the decades to come: clean, fresh water.

Stepping Into a Water-Stressed Future

From Africa’s Nile Basin and the deserts of the Middle East to the arid reaches of northern China, water resources are being burdened as never before in human history. There may be more or less the same amount of water held in the earth’s atmosphere, oceans, surface waters, soils, and ice caps as there was 50 — or even 50 million — years ago, but demand on that finite supply is soaring.

Consider that since 1900, the world population has skyrocketed from one billion to the cusp of seven billion today, with mid-range projections placing the global total at roughly 9.5 billion by mid-century. And it only took 12 years to add the last billion.

Unlike the United States — which is a water-abundant country by global standards — India is growing weaker with each passing year in its ability to withstand drought or other water-related climate shocks. India’s water outlook is cause for alarm not just because of population growth but also because of climate change-induced shifts in the region’s water supply. Depletion of groundwater stocks in the country’s key agricultural breadbaskets has raised water worries even further. Water scarcity is not some abstract threat in India. As Ashok Jaitly, director of the water resources division at New Delhi’s Energy and Resources Institute, told me this past spring, “we are already in a crisis.”

How the country manages its water scarcity challenges over the coming decades will have repercussions on food prices, energy supplies, and security the world over — impacts that will be felt here in the United States. And India is not the only country wrestling with the intertwined challenges of population growth and water scarcity.

Transboundary Tensions

Several of the world’s most strategically important aquifers and river systems cross one or more major international boundaries. Disputes over dwindling surface- and groundwater supplies have remained local and have rarely boiled over into physical conflict thus far. But given the challenges faced by countries like India, small-scale water disputes may move beyond national borders before the end of this century.

Looming global water shortages, warns a recent World Economic Forum report, will “tear into various parts of the global economic system” and “start to emerge as a headline geopolitical issue” in the coming decades.

This has become a national security issue for the United States. Any country that cannot meet population-linked water demands runs the risk of becoming a failed state and potentially providing fertile ground for international terrorist networks. For that reason, the United States is keeping close track of how water relations evolve in countries like Yemen, Syria, Somalia, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. It is also one of the reasons water security is a key goal of U.S. development initiatives overseas. For instance, between 2007 and 2008, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) invested nearly $500 million across more than 70 countries to boost water efficiency, improve water treatment, and promote more sustainable water management.

More Mouths to Feed, Limited Land to Farm

Water is a critical component of industrial processes the world over — from manufacturing and mining to generating energy — and shapes the everyday lives of the people who rely on it for drinking, cooking, and cleaning. But the aspect of modern society most affected by decreasing water availability is food production. According to the United Nations, agriculture accounts for roughly 70 percent of total worldwide water usage.

Global population growth translates into tens of millions of new mouths to feed with each passing year, straining the world’s ability to meet basic food needs. Given the finite amount of land on which crops can be productively and reliably grown and the constant pressure on farms to meet the needs of a growing population, the 20th and early 21st centuries have been marked by periodic regional food crises that were often induced by drought, poor stewardship of soil resources, or a combination of the two. As demographic change continues to rapidly unfold throughout much of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the ability of farmers and agribusinesses to keep pace with surging food demands will be continually challenged. Food shortages could very well emerge as a staple of 21st century life, particularly in the developing world.

Mirroring the growing burden on farmland will be a growing demand for water resources for agricultural use — and the outlook is not promising. According to a report from the International Water Management Institute in Sri Lanka, “Current estimates indicate that we will not have enough water to feed ourselves in 25 years’ time.”

As one of the world’s largest agricultural producers, the United States will be affected by this food crisis in multiple ways. Decreased food security abroad will increase demand for food products originating from American breadbaskets in California and the Midwest, possibly resulting in more intensive (and less sustainable) use of U.S. farmland. It may also drive up prices at the grocery store. Booming populations in east and south Asia could affect patterns of global food production, particularly if severe droughts spark downturns in food production in key Chinese or Indian agricultural centers. Such an outcome would push those countries to import huge quantities of grain and other food staples to avert widespread hunger — a move that would drive up food prices on the global market, possibly with little advance warning. Running out of arable land in the developing world could produce a similar outcome, Upmanu Lall, director of the Columbia Water Center at Columbia University, said via email.

Changing Tastes of the Developing World

Economic modernization and population growth in the developing world could affect global food production in other ways. In many developing countries, rising living standards are prompting changes in dietary preferences: More people are moving from traditional rice- and wheat-based diets to diets heavier in meat. Accommodating this shift at the global level results in greater demand on “virtual water” — the amount of water required to bring an agricultural or livestock product to market. According to the World Water Council, 264 gallons of water are needed to produce 2.2 pounds of wheat (370 gallons for 2.2 pounds rice), while producing an equivalent amount of beef requires a whopping 3,434 gallons of water.

In that way, the growing appeal of Western-style, meat-intensive diets for the developing world’s emerging middle classes may further strain global water resources. Frédéric Lasserre, a professor at Quebec’s Laval University who specializes in water issues, said in an interview about his book Eaux et Territories, that at the end of the day, it simply takes far more water to produce the food an average Westerner eats than it does to produce the traditional food staples of much of Africa or Asia.

Continue reading part two of “Turning Up the Water Pressure” here.

Sources: Columbia Water Center, ExploringGeopolitics.org, International Water Management Institute (Sri Lanka), Population Reference Bureau, The Energy and Resources Institute (India), United Nations, USAID, World Economic Forum, World Water Council.

Photo Credits: “Ganges By Nightfall,” courtesy of flickr user brianholsclaw, and “Traditional Harvest,” courtesy of flickr user psychogeographer. -

Guest Contributor

Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts: Quantifying the Integration of Population, Health, and Environment in Development

MOREIt makes intrinsic sense that integrated approaches working across development sectors are a good thing – especially when it comes to the complex issues facing people in developing countries and the environment in which they live. After all, integration avoids overlap and redundancies, and adds value to results on the ground. Yet, quantifying the benefit of integration has been difficult and to date, little on this topic has been published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Not anymore. Our article, “Integrated management of coastal resources and human health yields added value: a comparative study in Palawan (Philippines),” recently published in the journal Environmental Conservation, breaks new ground. Rigorous time-series data and regression analysis document evidence of different disciplines working together to produce synergies not obtainable by any one of the disciplines alone.

The article presents quasi-experimental research recently conducted in the Philippines that tested the hypothesis that a specific model of integration – one in which family planning information, advocacy, and service delivery were integrated with coastal resources management – yields better results than single-sector models that provide only family planning or coastal resources management services.

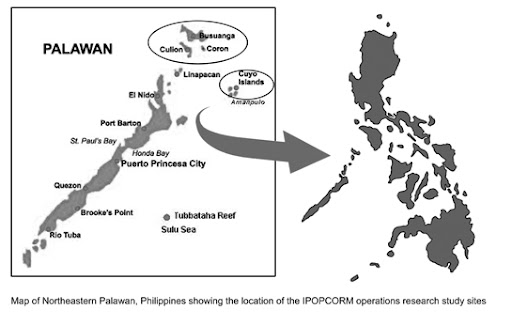

The study collected data from three island municipalities in the Palawan region of the Philippines, where the residents are dependent on coastal resources for their livelihoods. The integrated model was implemented in one municipality, while the single-sector models (one coastal resource management program and one reproductive health management program) were conducted in two separate municipalities.

The results of the study provide strong evidence that the integrated model outperformed the single-sector models in terms of improvements in coral reef and mangrove health; individual family planning and reproductive health practices; and community-level indicators of food security and vulnerability to poverty. Young adults – especially young men – at the integrated site were more likely to use family planning and delay early sex than at the sites where only family planning and reproductive health interventions were provided.

Coral reef health – as measured by a composite condition index – and mangrove health increased significantly at the integrated site, compared to the site where only coastal resource management interventions were provided. Data from the integrated site also showed a significant decline in the number of full-time fishers, as well as fewer people who knew someone that used cyanide or dynamite to fish – both factors that amplify a community’s vulnerability to food insecurity. Finally, the proportion of young people with income below the poverty threshold decreased by a significant margin in areas where the integrated population and coastal resources management (IPOPCORM) model was applied.

Let’s hope this research is just the beginning of a more thoughtful and effective approach to meeting multiple development goals in a lasting mannerEducational activities at the integrated site focused on illuminating the intrinsic relationship between fast-growing coastal communities in the Philippines and the diminishing health of the coral reefs and fisheries that they depend on for food and livelihoods. Community change agents, often fishermen and their families, talked to their neighbors and fellow fishers about the importance of planning and spacing families and establishing and respecting marine reserves to protect the supplies of food from the sea. They referred those interested in family planning to community-based social marketers of contraceptives or the nearest health center for other services.

These same community members also participated in activities to sustainably manage their coastal resources: working with local government officials to establish marine reserves, replant mangroves, serve as community fish wardens to patrol those reserves, test out alternative livelihoods such as seaweed farming, and start small businesses to diversify their income and reduce fishing pressure.

Development professionals should pay close attention to the conclusions of this study. In environmentally significant areas where human population growth is high, it will be difficult to sustain conservation gains without parallel efforts to address demographic factors and inequities in the distribution of health and family planning services. Integrating responses to population, health, and environment (PHE) issues provides an opportunity to address multiple stresses on communities and their environments and, as this study demonstrates, adds value in such a way that significantly improves community resilience and other outcomes.

This research allows those of us who believe strongly in integrating population, health, and environment programming to point to quantitative proof that the approach works. We now need to expand PHE programming to reach more people in other parts of the world where communities face a similar nexus of challenges. New initiatives have started taking the lessons from this research, applying them to new contexts in Africa and Asia, and scaling them up to reach many more in the Philippines.

Let’s hope this research is just the beginning of a more thoughtful and effective approach to meeting multiple development goals in a lasting manner in the places that need it most.Leona D’Agnes is the technical director of IPOPCORM, Joan Castro is the executive vice president of PATH Foundation Philippines Inc, and Heather D’Agnes is the Population, Health, Environment Technical Advisor in the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Office of Population and Reproductive Health.

Sources: BALANCED, Link TV, PATH Foundation Philippines Inc., World Wildlife Foundation.

Image Credit: Philippines village (adapted) and municipalities map courtesy of PATH Foundation Philippines Inc.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.