-

Ten Billion: UN Updates Population Projections, Assumptions on Peak Growth Shattered

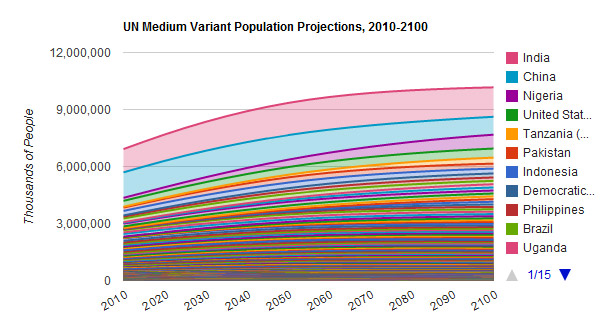

May 12, 2011 // By Schuyler NullMOREThe numbers are up: The latest projections from the UN Population Division estimate that world population will reach 9.3 billion by 2050 – a slight bump up from the previous estimate of 9.1 billion. The most interesting change however is that the UN has extended its projection timeline to 2100, and the picture at the end of the century is of a very different world. As opposed to previous estimates, the world’s population is not expected to stabilize in the 2050s, instead rising past 10.1 billion by the end of the century, using the UN’s medium variant model.

Topics: Afghanistan, Africa, China, demography, development, family planning, India, Iraq, Japan, Korea, Nigeria, population, security, UN, Yemen -

Family Planning as a Strategic Focus of U.S. Foreign Policy

May 11, 2011 // By Wilson Center Staff“Family Planning as a Strategic Focus of U.S. Foreign Policy,” by Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, was an input paper for the Council on Foreign Relations report, The Role of U.S. Family Planning Assistance in U.S. Foreign Policy. Excerpted from the introduction:MORE

Comprehensive policies that incorporate demography, family planning, and reproductive health can promote higher levels of stability and development, thereby improving the health and livelihood of people around the world while also benefiting overarching U.S. interests. U.S. foreign aid will be more effective if increased investments are made in high population-growth countries for reproductive health and family planning programs. These programs are cost-effective because they help reduce the stress that rapid population growth places on a country’s economic, environmental, and social resources.

Family Planning and Reproductive Health Programs

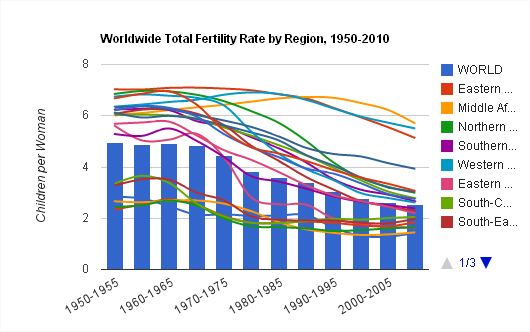

Family planning and reproductive health programs have successfully reduced the world’s population growth rate, propelled economic development, and improved women’s lives across the world. When people, and especially women, are given the opportunity and technology to limit their family size, they often choose to do so.

Population trends are motivated by three demographic forces: fertility, mortality, and migration. Although they can have dramatic effects on national and local populations, mortality and migration in particular have relatively little influence globally. Across the world, mortality rates have declined to a point where most children born today live to reach their own reproductive years, though much work remains to reduce the effect of communicable diseases and improve nutrition among the young. Meanwhile, three percent of the world’s population currently lives outside of their birth-countries. Therefore, while migration is increasing and an important demographic force, it does not occur at a scale large enough to significantly affect global-level demography.

Fertility rates currently are – and in the short-term will remain – the most important driver of global demographic trends. The total fertility rate, or average number of children born to each woman, has been estimated at 2.7 for the period between 2000 and 2005, a decline from 3.6 children per woman in the early 1980s. Given this decline, population projections generally assume future declines in fertility rates. For example, the widely cited “medium-fertility variant,” which is the United Nations’ projection of a world population growing from 6.9 billion in 2010 to 9.1 billion by 2050, relies upon an assumption that the global fertility rate will decline by 24 percent to two children per woman. However, if fertility rates remain constant at current levels, the world’s population would reach 11 billion by 2050. Fertility rates, whether they decline or remain at current levels, are not distributed evenly among countries and regions.

Continue reading or download the full report, “Family Planning as a Strategic Focus of U.S. Foreign Policy,” from the Council on Foreign Relations. -

Population and Environment Connections: The Role of Family Planning in U.S. Foreign Policy

May 11, 2011 // By Geoffrey D. Dabelko“Population and Environment Connections,” was an input paper for the Council on Foreign Relations report, Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ensuring U.S. Leadership for Healthy Families and Communities and Prosperous, Stable Societies.MORE

Current global population growth rates are not environmentally sustainable and the increasing demands of a growing global population are increasingly straining supplies of food, energy, and water. The expected consequences of climate change will stress resources further. Population growth dynamics compound challenges presented by increased resource consumption from a rising global middle class, making the world’s population, and the quality and quantity of natural resources, top priorities for governments and the public alike.

Governments and multilateral organizations must recognize the relationship between resource demand, resource supply, and resource degradation across disparate economic and environmental sectors. Formulating appropriate and effective responses to growth-induced resource complications requires both a nuanced understanding of the problem and the use of innovative approaches to decrease finite resource consumption.

Family planning and integrated population, health, and environment (PHE) approaches offer opportunities to address such concerns. These efforts recognize the importance of population-environment linkages at the macro-level. They also operate at the household, community, and state levels, empowering individuals and decreasing community vulnerability by building resilience in a wider sustainable development context. PHE approaches embrace the complex interactions of population, consumption, and resource use patterns. To paraphrase Brian O’Neill, a leading scholar on population-climate connections, PHE approaches offer a way forward that is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring. Addressing population-environment links is an essential step to tackling global sustainability crises.

Download “Population and Environment Connections” from the Council on Foreign Relations. -

Report: Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy

May 10, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffMOREThe original version of this brief, by Isobel Coleman of the Council on Foreign Relations, is based on the report, Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ensuring U.S. Leadership for Healthy Families and Communities and Prosperous, Stable Societies, by Isobel Coleman and Gayle Lemmon.

Click here for the interactive version (non-Internet Explorer users only).

U.S. support for international family planning has long been a controversial issue in domestic politics. Conservatives tend to view family planning as code for abortion, even though U.S. law, dating to the 1973 Helms Amendment, prohibits U.S. foreign assistance funds from being used to pay for abortion. Indeed, increased access to international family planning is one of the most effective ways to reduce abortion in developing countries. Investments in international family planning can also significantly improve maternal, infant, and child health. Support for international voluntary family planning advances a wide range of vital U.S. foreign policy interests – including the desire to promote healthier, more prosperous, and secure societies – in a cost-effective manner.

Saving Lives of Mothers and Children

More than half of all women of reproductive age in the developing world, some 600 million women, use a form of modern contraception today, up from only 10 percent of women in 1960. This has contributed to a global decline in the average number of children born to each woman from more than six to just over three. Despite these gains, an estimated 215 million women globally – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia – are sexually active but are not using any contraception, even though they want to avoid pregnancy or delay the birth of their next child. With the world’s population poised to cross the seven billion mark later in 2011, and expected to grow by nearly 80 million people annually for several more decades, global unmet need for family planning is likely to increase.

Studies have shown that contraception could reduce maternal deaths by a third, from approximately 360,000 to 240,000; reduce abortions in developing countries by 70 percent, from 35 million to 11 million; and reduce infant mortality by 16 percent, from 4 million to around 3.4 million.

For a woman in the developing world, the lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy is still one of the greatest threats she will face. In developed countries, 1 out of 4,300 women will lose her life as a consequence of pregnancy, compared to sub-Saharan Africa, where that figure soars to 1 in 31, and Afghanistan, where the lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy is 1 out of 7.

Unsafe abortions are one factor contributing to high maternal death rates. As of 2008, 47,000 abortion-related maternal deaths occur annually, accounting for 13 percent of all maternal deaths. Filling the unmet need for modern family planning would lead to a reduction in mistimed pregnancies and a significant decline in abortions and abortion-related health complications. In 2000 alone, if women who wished to postpone or avoid childbearing had access to contraception, approximately 90 percent of global abortion-related and 20 percent of obstetric-related maternal deaths could have been averted.

Maternal mortality has a devastating and irreversible effect on children and families. Indeed, countries with the highest maternal mortality rates also experience the highest rates of neonatal and childhood mortality. When a mother dies, her surviving newborn’s risk of death increases to 70 percent.

Family planning presents an opportunity to curb maternal and under-five deaths not simply by giving women of all ages the ability to determine their family size, but by enabling women to delay pregnancy until at least age 18 and to space and plan their births. In this way, modern contraceptive methods help women avoid high-risk pregnancies. Studies suggest that short pregnancy intervals (when the pregnancy occurs less than twenty-four months after a live birth) are associated with an increased risk of maternal and under-five mortality. In fact, if all mothers were to wait at least 36 months to conceive again, it is estimated that 1.8 million deaths of children under five could be prevented annually.

Enhancing International Security

While much of the developed world is experiencing population stability or even decline, many countries in the developing world continue to see rapid population growth. Population imbalances have emerged as a serious issue affecting economic opportunity, global security, and environmental stability. Ongoing civil conflicts, radicalism, weak governance, and corruption are endemic problems for many fragile states. While high fertility rates are not the cause of their problems, they do complicate the challenges these countries face in trying to reduce poverty, achieve per capita income growth, provide education and productive opportunities for youth, and address increasing shortages of natural resources.With the world’s population poised to cross the 7 billion mark later in 2011, and expected to grow by nearly 80 million people annually for several more decades, global unmet need for family planning is likely to increase.

Yemen, for example, has the highest rate of unmet need for family planning of any country. Its population has doubled in less than 20 years, and it has the world’s second-youngest population. High fertility – around six children per woman – taxes Yemen’s infrastructure, education and health systems, and environment. In addition, its labor force is growing at a pace much faster than the growth of available jobs, resulting in high youth unemployment. Increasing access to family planning would help improve Yemen’s long-term prospects for achieving per capita growth and stability. Conversely, continued high fertility rates will only deepen Yemen’s current crises.

Many countries experiencing fast population growth – like Yemen – do not have the capacity to harness the potential of their young populations. In these cases, high fertility rates can lead to a vicious cycle of poverty at the community, regional, and national levels. Rapidly growing populations are also more prone to outbreaks of civil conflict and undemocratic governance. Eighty percent of all outbreaks of civil conflict between 1970 and 2007 occurred in countries with very young populations. Demographers have shown that the statistical likelihood of civil conflict consistently decreases as countries’ birth rates decline.

Countries with the highest population growth rates face real resource constraints, particularly arable land and clean water. As of 2010, 40 percent of populations in more than 35 countries have insufficient access to food, with the largest concentration in central and eastern sub-Saharan Africa. Given that many of these food-insecure countries will continue to experience significant population growth in decades ahead, malnutrition will remain a challenge.

Continue reading at the Council on Foreign Relations or download the full report, Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ensuring U.S. Leadership for Healthy Families and Communities and Prosperous, Stable Societies.

Isobel Coleman is a senior fellow for U.S. foreign policy; director of the Civil Society, Markets, and Democracy Initiative; and director of the Women and Foreign Policy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Sources: Council on Foreign Relations, Population Action International, Population Reference Bureau, UNFPA, World Health Organization.

Chart Credit: Arranged by Schuyler Null, data from UN Population Division, World Population Prospects, 2010 Revision. -

From the Wilson Center

A New Security Narrative: What’s America’s Story for the 21st Century?

MOREWe rarely had to question our place in the world during World War II or the Cold War when good guys and bad guys were easier to identify. A clear narrative, whether in the form of opposing Hitler or containing the spread of “The Evil Empire,” fueled our sense of global mission. Sure there were disagreements, but the big picture (and the big enemy) loomed large.

Our sense of realities, large and small, begins with the stories that frame our understanding of the events around us. The fall of the USSR took the wind out of the sails of our mythic sense of purpose. We were still “us,” but we now lacked a “them.”

A security narrative often emerges from our collective sense of threat assessment. It’s not only about what we stand for, but also what we stand against. On that fateful day of September 11, 2001, many believed that we had found the enemy that would provide the story lacking from our national security narrative since the fall of the Soviet empire. But an ill-defined foe lacking a nation-state home has only contributed to our post-Cold War drift. When we ask ourselves why we are committing military might in Libya (or Afghanistan, or Iraq), we’re really asking bigger questions. What is our purpose in the world? What is the story that defines our friends and our foes? And what does that story tell us about when to sit back or step up? When to watch or when to act?

The lack of a storyline also gives those who hate us the opportunity to define us as evil. So it becomes ever more urgent to start the conversation and to provide a non-partisan forum for what is bound to be a difficult deliberation. When Jane Harman left Congress to accept the leadership post at the Wilson Center, she brought her sense that toxic partisanship prevents Congress from addressing the biggest questions facing the nation in a productive and nonpartisan manner. Under her leadership, the Wilson Center has begun the “National Conversation” series to tackle the toughest issues.

The recently held inaugural event showed great promise. Two active military officers, Captain Wayne Porter (USN) and Colonel Mark Mykleby (USMC), writing under the pseudonym, “Mr. Y,” provided the framework for the discussion. Their vision for a new U.S. security story was presented in a white paper titled, “A National Strategic Narrative.” Their stated purpose is to provide a framework through which to view policy decisions well into the 21st century.

The encounter was lively and challenging, sometimes provocative, but always civil. I can summarize the immediate outcome by reporting a consensus that a narrative is missing and needed. It was a good start, but the discussion needs to continue until we reach a national consensus and not just one among five panelists and a moderator. I will not go into great detail in recapping the arguments and ideas presented, but will instead offer a contribution from each participant to whet your appetite.

Anne-Marie Slaughter, Princeton professor and former Director of Policy Planning for the U.S. Department of State began the session with a summary of the white paper, describing the changing nature of power and influence:We were never able to control international events but we had a much better possibility during the Cold War when you essentially had a bipolar world with two principal actors than we do in a world of countless state and non-state actors. Nobody controls anything in the 21st century, indeed it’s just not a very good century to be – it’s not a good time to be a control freak. [Laughter] Whether it’s your e-mail or global events it’s sort of the same problems. What you can do is influence outcomes. So we have to start by saying it’s an open system; you can’t control it but you can build up your credible influence.

Brent Scowcroft, National Security Advisor to two U.S. presidents, provided an historical framework for the discussion:I think we’re facing a historical discontinuity. The Treaty of Westphalia recognized the existence of the nation-state system codified it and so on. That was a replacement for the feudal system where our sovereignty was vague, divided between kings and princes and landowners and religious leaders. It created a new system and I think the epitome of the nation-state system was the 20th century. I think that globalization writ large is changing that system and globalization is eroding national borders. The financial crisis of 2008 showed us we’ve got a global economic system, what happened in one country spread immediately around. It also showed we don’t have a global way to deal with a global economic situation. Now, this force of globalization to me the best way to look at it is akin to the force of industrialization 250 years ago. Industrialization really created the modern nation state with a lot more power over its citizens to deal with issues than the earlier Westphalia state system had. And it brought the state together. It made it more powerful. Globalization is reacting the same way but in the opposite direction. It is diluting the power of the nation state to deal with the important things.

Thomas Friedman, Pulitzer-prize winning columnist for The New York Times, described the difference between virtual and real action:Exxon Mobil, they’re not on Facebook, they’re just in your face. [Laughter] Peabody Coal, they don’t have a chatroom. They’re in the cloakroom of the U.S. Congress with bags of money. So if you want to change the world, you gotta get out of Facebook and into somebody’s face whether that’s in the U.S. Congress or Tahrir Square. You’ll say, why I blogged on it. I blogged on it, really? That’s like firing a mortar into the Milky Way Galaxy, okay. [Laughter] There is a faux sense of activism out there that is really dangerous. The world, your world, may be digital but politics is still analog and we’ve kind of gotten away from that. Egypt changed. Yes, Facebook was hugely important in organizing people, but the fundamental change happened because a million people showed up in Tahrir Square.

Steve Clemons, founder of the American Strategy Program at the New America Foundation, added this thought on the essence of globalization:What globalization really is, is the disruption of cartels. What blogging is, individual blogging is saying is, I’m not gonna wait for The New York Times editor to tell me no any more or [laughter] to say yes three weeks from now. You know, it is the disruption of cartels and that is happening in every sector of society.

Robert Kagan, senior fellow with The Brookings Institution and a former State Department Policy Planning Officer, cautioned against rushing to utopian conclusions about the impact of our new levels of interconnectedness:Let me just give you an example of how even something new doesn’t necessarily change things the way we want them to or the way we expect them to. I’m positive by the way that human nature is not new. So you’re kind of dealing with the same beast, and I use the term advisably, as you’ve been dealing with for millennia. Let’s talk about the fact that everyone can communicate with each other on the internet. You know, when people communicate with each other especially across national boundaries sometimes it makes them grow closer. Sometimes it makes them hate each other more. If you read the Internet in China now it’s hyper nationalistic. Now, you can argue that because that’s where the government channel said and because they don’t let anybody else or anything else or you could say the Internet is a great vehicle for the Chinese people to express their hatred of the Japanese people. It certainly is doing that now. So does that mean the Internet is going to bring nations closer and solve problems? Not necessarily.

Representative Keith Ellison (D-MN), talked about the expectations of youth and how demographics will be a key consideration when defining a narrative:The Middle East is on my mind a lot these days, what it means if you have all these societies where 50 percent of the population is under 18 years old? You know this is – this has big implications. I mean, this is a demographic reality that is going to have vast implications for the United States. So one thing is it’s not going away because lots of these people who are 18 years old, their cohort just moves through. You know, they’re going to be there a long time and they have demands, they’re going to have needs, they’re going to have expectations. You mentioned justice. They expect us to act justly. And I, when people talk about anti-Americanism, for me part of what’s going on is unmet expectations not just ‘we don’t like it.’

For this abbreviated summary of the discussion, I give the final cautionary word to Steve Clemons, who had this to say in response to an audience question about how to begin the process of constructing a new narrative:This is a town of risk-averse institutions, a town of inertia, a town of vested interests. It’s not a town that really embraces the notion of how do you pivot very quickly and rapidly in a different direction. So, fundamentally you need to begin putting out narratives like this.

A transcript and video of the event is available from the Wilson Center and additional coverage can also be found right here on The New Security Beat.

John Milewski is the host of Dialogue Radio and Television at the Woodrow Wilson Center and can also be followed on The Huffington Post or Twitter.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “1989 – Berlin, Germany,” courtesy of flickr user MojoBaer.Topics: Afghanistan, demography, foreign policy, From the Wilson Center, Iraq, Libya, Middle East, military, security -

Population Growth and Climate Change Threaten Urban Freshwater Provision

May 6, 2011 // By Emanuel FeldMOREBy 2050, more than one billion urban dwellers could face perennial freshwater shortages if major improvements are not made to water management practices and infrastructure, according to a recent study published in the journal PNAS, “Urban Growth, Climate change, and Freshwater Availability.” These challenges will arise as hydrologic changes due to climate change compound “an unprecedented wave of urban growth,” with nearly three billion additional urban residents forecast by 2050. “It is a solvable problem,” the study argues, “but one that will take money, time, political will, and effective governance.”

Using demographic data from the Earth Institute at Columbia University, as well as a variety of climate and city-level demographic scenarios, the researchers estimate per-capita water availability for cities in the developing world, where urban growth will be most rapid. They advise, however, that their findings should be taken as conservative estimates, since the study assumes cities can use all nearby water and does not account for key challenges relating to water quality and delivery to urban centers.

In 2000, 150 million people in developing countries lived in urban areas that could not support their own water requirements (i.e. less than 100 liters available per person per day). By 2050, according to the study, urban population growth alone could bring this figure to 993 million and more than three billion could face intermittent shortages at least one month out of the year. When the researchers expanded the area on which cities can draw upon to include a 100 km buffer zone, these values drop to 145 million and 1.3 billion, respectively.

However, once climate and land use change are included in the models, the aggregate number of people facing perennial shortages rises a further 100 million, if only water stores within the urban area are considered, or 22 million, for the 100 km buffer zone model.

Remarkably, these aggregate figures differ very little among the various demographic and climate scenarios. The particularities of the challenge do however vary at the regional level. Perennial water shortage will generally be limited to cities in the Middle East and North Africa. Seasonal water shortages, on the other hand, will be geographically widespread, although rapidly urbanizing India and China will be especially hard hit.

The study acknowledges the temptation to view water shortage “as an engineering challenge.” Still, the lead author, Rob McDonald of The Nature Conservancy, cautions against exclusive reliance on grey infrastructure solutions (e.g. canals and dams) in an article for Nature Conservancy, saying:Some new infrastructure will be needed, of course – that’s the classic way cities have solved water shortages. But especially in parts of the world where there’s lots of cities, just going out farther or digging deeper to get water can’t be the only solution.

Instead, McDonald and co-authors Pamela Green, Deborah Balk, Balazs M. Fekete, Carmen Revenga, Megan Todd, and Mark Montgomery, emphasize the need for cities to encourage more efficient water use by their industrial and residential sectors, as well as the potential to engage the water-intensive agriculture sector in surrounding rural areas.

“Bottom line,” McDonald said in an interview with Robert Lalasz of The Nature Conservancy’s Cool Green Science blog, “don’t think of those high numbers as a forecast of doom. They are a call to action.”

Emanuel Feld is a student at Yale University studying economics and the environment.

Sources: Cool Green Science, PNAS, The Nature Conservancy.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Chennai prayed too hard…. Part I,” courtesy of flickr user Pandiyan.Topics: Africa, climate change, development, environment, Middle East, population, urbanization, water -

From the Wilson Center

Watch ‘Dialogue’ TV on Integrating Development, Population, Health, and the Environment

MORELast week on the Wilson Center’s Dialogue radio and television program, host John Milewski spoke with Geoff Dabelko, director of ECSP, Roger-Mark De Souza, vice president for research and director of the Climate Program for Population Action International, and George Strunden, vice president of Africa programs for the Jane Goodall Institute. They discussed the challenge of integrating population, health, and environmental programs (PHE) to address a broad range of livelihood, development, and stability issues. [Video Below]

“Many times that we tackle development or poverty and human well-being challenges…we do it in an individual sector – the health sector, or agriculture sector, or looking at issues of water scarcity – and it makes sense in many respects to take those individual focuses,” said Dabelko. “But of course people living in these challenges, they’re living in them together…so both in terms of understanding the challenges…and then in responding to those challenges, we have to find ways to meet those challenges together.”

De Souza noted that the drive for integrated development stems from the communities being served, not necessarily from outside aid groups. “We’ve seen that there’s a greater impact because there’s longer sustainability for those efforts that have an integrated approach,” he said. “There’s a greater understanding and a greater appreciation of the value that [PHE] projects bring.”

Strunden said that the Goodall Institute has found similar success in tying health efforts with the environment in places where previously conservation work alone had been unsuccessful.

The panelists also discussed the role of population in broader global challenges, including energy, water, and food scarcities, and women’s rights.

Dialogue is a co-production of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and MHz Networks. The show is also available throughout the United States on MHz Networks, via broadcast and cable affiliates, as well as via DirecTV and WorldTV (G19) satellite.

Find out where to watch Dialogue where you live via MHz Networks. You can send questions or comments on the program to dialogue@wilsoncenter.org. -

Watch: Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba on Population and National Security

April 28, 2011 // By Schuyler Null“Long-term trends really are what shape the environment in the future,” said Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba in this interview with ECSP. “As we’ve seen recently with…revolution in North Africa, it’s the long-term trends that act together for these things to happen – I like to say demography is not usually the spark for a conflict but it’s the fodder.”MORE

Sciubba is the Mellon Environmental Fellow in the Department of International Studies at Rhodes College. In her new book, The Future Faces of War: Population and National Security, she discusses the importance of demographic trends in relation to security and stability, including age structure, migration, youth bulges, population growth, and urbanization.

One of the most important things to emerge from the book, said Sciubba, is that countries that are growing at very high rates that are overwhelming the capacities of the state (like many in sub-Saharan Africa) really will benefit from family planning efforts that target unmet need.

Afghanistan, for example, “has an extremely young age structure,” Sciubba pointed out. “So if you’re trying to move into a post-conflict reconstruction atmosphere…you absolutely have to take into account population and the fact that it will continue to grow.”

“Even if there are major moves now in terms of reducing fertility, they have decades ahead of this challenge of youth entering the job market,” Sciubba said. “Thousands and thousands more jobs will need to be created every year, so if you have a dollar to spend, that’s a really good place to do it.”

For more on Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba and The Future Faces of War, see her book launch at the Wilson Center with Deputy Under Secretary Kathleen Hicks of the Department of Defense (video) and some of her previous posts on The New Security Beat.Topics: Afghanistan, Africa, demography, family planning, Middle East, military, population, security, video, youth

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.