-

Elizabeth Malone on Climate Change and Glacial Melt in High Asia

› “There’s nothing more iconic, I think, about the climate change issue than glaciers,” says Elizabeth Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Malone served as the technical lead on “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerability to Glacier Melt Impacts,” a USAID report released in late 2010 that explores the linkages between climate change, demographic change, and glacier melt in the Himalayas and other nearby mountain systems.

“There’s nothing more iconic, I think, about the climate change issue than glaciers,” says Elizabeth Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Malone served as the technical lead on “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerability to Glacier Melt Impacts,” a USAID report released in late 2010 that explores the linkages between climate change, demographic change, and glacier melt in the Himalayas and other nearby mountain systems.

Describing glaciers as “transboundary in the largest sense,” Malone points out that meltwater from High Asian glaciers feeds many of the region’s largest rivers, including the Indus, Ganges, Tsangpo-Brahmaputra, and Mekong. While glacial melt does not necessarily constitute a large percentage of those rivers’ downstream flow volume, concern persists that continued rapid glacial melt induced by climate change could eventually impact water availability and food security in densely populated areas of South and East Asia.

Rapid demographic change has potentially factored into accelerated glacial melt, even though the connection may not be a direct one, Malone adds.

Atmospheric pollution generated by growing populations contributes to global warming, while black carbon emissions from cooking and home heating can eventually settle on glacial ice fields, accelerating melt rates. Given such cause-and-effect relationships, Malone says that rapid population growth and the continued retreat of High Asian glaciers are “two problems that seem distant,” yet “are indeed very related.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

Developing a Blueprint for Addressing Glacier Melt in the Region

Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia

›“Glacier melt is part of larger hydrologic and climate systems, so effective programs will be cross-sectoral and yield co-benefits,” said Elizabeth L. Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, speaking at the Wilson Center on November 16. “Looking more closely at glacier melt, we come to understand that upstream actions and choices have a potentially huge effect on downstream communities,” added Kristina Yarrow, health advisor at the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Asia and Middle East Bureaus.

Malone and Yarrow were joined by Mary Melnyk, senior advisor for natural resource management at USAID’s Asia and Middle East Bureaus, to discuss the agency’s new report, “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerabilities to Glacier Melt Impacts,” prepared by Malone in collaboration with CDM International and TRG. “This report is a move towards mainstreaming climate change across the development portfolio to ensure enduring success of our investments,” Melnyk said.

Mainstreaming Climate Change

Providing information about the science, vulnerabilities, and current efforts to respond to environmental change and glacier melt in Asia, the new report also features a number of practical, cross-sectoral approaches to addressing glacial retreat in Asia that, if implemented well, could produce multiple benefits. The report highlights the complexity of the issues surrounding glacier melt in the region, and the critical need to prepare today for future environmental changes.

“Climate change in general, and glacier melt specifically, can potentially impact all sectors: economic growth, governance, and health,” Melnyk said. Because there is a lack of scientific knowledge on glacial retreat in Asia and limited financial and human resources to address these issues, it is critical to maximize results through programs that will provide environmental, health, and development co-benefits.

“The challenge is that, in practice, addressing issues of climate change and other environmental security issues still are not a part of the day-to-day business across sectors,” Melnyk said. This report is a first step in the right direction to raise awareness and action on these issues and “although there is uncertainty, we need to move forward – the time to act is now,” she concluded.

Multiple Sectors, Multiple Benefits

“Cross-sector collaboration and programs, when done correctly, can have a much greater impact than when doing a vertical program within a specific sector,” Yarrow said, stressing the importance of multidisciplinary approaches to address environment, health, and development issues. Understanding the health impacts of climate-related environmental change now can help prepare us to address these specific impacts in the future.

“On a global scale, there is indeed a relationship between population growth, environmental change, and development,” Yarrow said. In Asia, stress on water resources due to climate change and rapid population growth will likely exacerbate health problems caused by lack of clean water. Proactively expanding and improving programs that address the causes and effects of diarrheal disease and under-nutrition can help address these vulnerabilities and make communities more resilient.

“Finding innovative ways to improve access to and integrate family planning messages and services into climate adaptation programs will also yield some important co-benefits,” Yarrow said. Family planning can slow population growth, which could help reduce projected demand for water supplies, as well as potentially reduce the amount of water pollution.

Yarrow also added that “population growth affects glacier melt indirectly through the consumption of resources that exacerbate black carbon.” Black carbon, which is produced by cooking and heating with biomass fuels, contributes to regional climate change and severe health problems, including respiratory illness and pneumonia. Accompanied by efforts to promote alternative fuels, family planning could reduce black-carbon emissions, significantly improve health, and strengthen community resilience to climate change.

“Though challenging, integrating across sectors is absolutely essential – we’re not experts yet, but we’re definitely getting better,” Yarrow said. “Understanding and addressing the multiple issues like climate change, poor health, poverty, dependence on natural resources, and governance challenges that these communities are dealing with in a comprehensive and holistic fashion will improve results.”

Responding to Glacier Melt

“We simply do not have the kind of broad-scale knowledge that we would like to have,” Malone said. Current data on glacier melt is scarce and very few direct measurements of glacier volume exist, making calculations of glacier retreat difficult. Moving forward, it is critical to respond to this lack of information by improving regional scientific cooperation on glaciers, snowpack, and water resources in High Asia, and strengthening climate and water monitoring capacity.

“Even the smallest amounts of glacier-melt contribution correspond to the regions of the highest population, so any change in water supply has large implications,” Malone said. Glaciers may not be disappearing as fast as had been previously thought, but “climate change is happening in the Himalayas and is having an effect.”

“If systems – both human and ecological – are already stressed, they are less able to be resilient in the face of changes. But the good news is that we can take actions now that will be crucially important to how societies can respond in the future,” Malone said.

Implementing cross-sector projects can help to target places where environmental, economic, health, and even security issues overlap. Focusing on water resource management, ecosystems, and the needs of high-mountain communities, as well as mitigating climate change by reducing emissions of black carbon, can help reduce both direct and indirect vulnerabilities and improve resilience to future changes.

“The results of this report allow USAID and others to grasp the complexity of these issues, understand the critical gaps, and to respond to the changes in the glaciers to come,” Melnyk said. The next step is applying the knowledge gathered in the report to practitioners in the field and in policy discussions.

“A crucial role USAID can play is to link partners in the government and private sectors to build capacity and spark synergies among new initiatives to really integrate new initiatives with concerns about glacier melt,” Malone concluded.

Photo Credit: “Nepal Sagamartha Trek,” courtesy of flickr user mckaysavage. -

Food and Environmental Insecurity a Factor in North Korean Shelling?

›November 24, 2010 // By Schuyler NullJust two days before dozens of North Korean artillery shells fell on the island of Yeonpyeong off the west coast of Korea, a UN study reported that the DPRK was facing acute food shortages heading into the winter.

In a New York Times report, Choi Jin-wook, of the Korea Institute for National Unification in Seoul, called food “the number one issue.” While Choi just last month praised the resumption of food aid from the South to the North as a “starting point of a new chapter in inter-Korean relations,” she told the Times Wednesday that the North is “in a desperate situation, and they want food immediately, not next year.”

North Korea’s motives are notoriously indecipherable and this latest incident is no exception, but the regime has in the past sought to distract from domestic problems by inciting the international community (the sinking of the Cheonan being the other latest prominent example).

Infrastructure has always been primitive in the North under the DPRK regime, but the country’s tenuous food security situation was made worse this last year by an unusually long and severe winter followed by heavy flooding in the summer. Flooding was so bad during August and September, that the normally silent regime publically announced details of rescue operations around the northern city of Sinuiju. The joint FAO/WFP report put out by the UN does not predicate production will significantly recover in the next year and estimates an uncovered food deficit of 542,000 tons for 2010/11.

“A small shock in the future could trigger a severe negative impact and will be difficult to contain if these chronic deficits are not effectively managed,” Joyce Luma of the World Food Program told The New York Times.

For more on the severe weather events of this summer, including the flooding that impacted the DPRK and pushed the Three Gorge Dam to its stress limits in China, the impact of scarcity and climate change on the potential for conflict, and the intersection of food security and conflict elsewhere, see our previous coverage on The New Security Beat.

Sources: Christian Science Monitor, Food and Agriculture Organization, Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, UN, Washington Post, World Food Program.

Image Credit: Google Maps. -

Jon Barnett on Climate Change, Small Island States, and Migration

›

Contrary to the iconic image of lapping waves submerging low-lying countries, few Pacific islanders are emigrating from their homes due to climate change, according to Australian geographer Jon Barnett of the University of Melbourne.

-

Pakistan After the Floods: A Continuing Disaster

›September 29, 2010 // By Hannah Marqusee

A month after Pakistan’s worst flood in 80 years, millions remain without access to food, clean water, or health care.

-

Historic Floods Plague Pakistan

›August 19, 2010 // By Shawna Cuan“Staggered by the scale of destruction from this summer’s catastrophic floods, Pakistani officials have begun to acknowledge that the country’s security could be gravely affected,” reports the Washington Post. The Pakistani government – already cash-strapped between fighting “the war on terror” and trying to prevent an economic collapse – now faces recovering from the worst flooding in over 80 years.

-

Floods, Fire, Landslides, and Drought: The Guardian’s “Weather Crisis 2010”

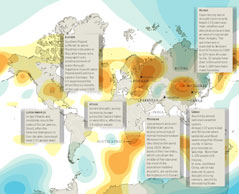

› From the Guardian’s DataBlog comes an excellent overview of some of the extreme weather affecting the globe this summer, from the devastating floods in Pakistan which have inflicted “huge losses” to crops and exacerbated an already tenuous security situation, to the wildfires in Russia which have smothered the capital in dangerous smog and crippled domestic wheat supplies.

From the Guardian’s DataBlog comes an excellent overview of some of the extreme weather affecting the globe this summer, from the devastating floods in Pakistan which have inflicted “huge losses” to crops and exacerbated an already tenuous security situation, to the wildfires in Russia which have smothered the capital in dangerous smog and crippled domestic wheat supplies.

“Global temperatures in the first half of the year were the hottest since records began more than a century ago,” writes author and graphic artist Mark McCormick.

The orange areas of the map represent high pressure systems and the blue, low pressure systems, which as explained by Peter Stott of the Met Office, are important indicators of the rare climatic conditions that caused this summer’s abnormal conditions across Eurasia.

The flooding in Pakistan has garnered the most international attention, having now affected more people than the 2004 tsunami, 2010 Haiti earthquake, and 2005 Kashmir earthquake combined. Other highlighted areas of the map include flooding in Poland and Germany, drought in England, mudslides in Latin and South America, record-breaking drought and hunger in West Africa, and flooding and landslides in China, which recently pushed the world’s largest hydroelectric dam to its limit and have now been blamed for more than 1,000 deaths.

Although it does a good job highlighting the frequency and severity of extreme weather events this summer, it’s important to note that the map only covers events in July and August. That leaves out the “1000-year” floods in Tennessee this May as well as the heavy snowfall seen in the Northeast United States and the winter of “white death” in Mongolia earlier this year, which also severely disrupted local and national infrastructure as well as a great many people’s livelihoods.

Sources: Agence France-Presse, BBC, Guardian, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, New York Times, Telegraph, UN Dispatch.

Image Credit: “Weather Crisis 2010” by Mark McCormick, courtesy of Scribd user smfrogers and The Guardian. -

Flooded With Food Insecurity in Pakistan

›The floods sweeping across Pakistan have caused widespread destruction, ruined livelihoods, displaced millions, and sparked a food crisis. Food prices have skyrocketed across the country as miles of farmland succumb to the deluge, including 1.5 million hectares in Punjab province, Pakistan’s breadbasket and agricultural heartland.

Food insecurity is now rife across the country — yet even before the floods, millions of Pakistanis struggled to access food. Back in 2008, the UN estimated that 77 million Pakistanis were hungry and 45 million malnourished. And while many developing nations have begun to recover from the global food crisis of 2007-08, Pakistan’s food fortunes have remained miserable. Throughout 2010, Pakistan’s two chief food staples, rice and wheat, have cost 30 to 50 percent times more than they did before the global food crisis. Drought, rampant water shortages, and conflict have intensified food insecurity in Pakistan in recent months.

A new edited book volume published by the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, Hunger Pains: Pakistan’s Food Insecurity, examines the country’s food insecurity. The book has already been the subject of a news story and an editorial in the Pakistani newspaper Dawn. The book, edited by Michael Kugelman and Robert M. Hathaway, is based on the 2009 Wilson Center conference of the same name. It assesses food supply challenges, access issues, governance constraints, social and structural dimensions, gender and regional disparities, and international responses.

The book makes a range of recommendations. These include:- Declare hunger a national security issue. Since some of Pakistan’s most food-insecure regions lie in militant hotbeds, hunger should be linked to defense, and food provision projects should be given ample public funding.

- Diversify the crop mix so that Pakistan’s agricultural economy revolves around more than wheat and rice. The country should accord more resources to crops that are less water-intensive and more nutritious.

- Give schools a central focus in food aid and food distribution. Using schools as a venue for food distribution gives parents powerful incentives to send their children to school.

- Tackle the structural dimensions. Strengthening agricultural institutions, improving infrastructure and storage facilities, and injecting capital into a stagnant farming sector are all key to making Pakistan more food-secure. Yet unless Pakistan deals with poverty, landlessness, and entrenched political interests in agriculture, food insecurity will remain.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Photo Credit: “Chitarl, Pakistan” where floods damaged the way over Lawari pass and killed five in August 2006. Courtesy of flickr user groundreporter

Showing posts from category flooding.