-

Reform Aid to Pakistan’s Health Sector, Says Former Wilson Center Scholar

›August 5, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffExcerpt from op-ed by Samia Altaf and Anjum Altaf in Dawn:

WE must state at the outset that we have been wary of, if not actually opposed to, the prospect of further economic assistance to Pakistan because of the callous misuse and abuse of aid that has marked the past across all elected and non-elected regimes.

We are convinced that such aid, driven by political imperatives and deliberately blind to the well-recognised holes in the system, has been a disservice to the Pakistani people by destroying all incentives for self-reliance, good governance and accountability to either the ultimate donors or recipients.

Even without the holes in the system the kind of aid flows being proposed are likely to prove problematic. Over half a century ago, Jane Jacobs, in a brilliant chapter (Gradual and Cataclysmic Money) in a brilliant book (The Death and Life of Great American Cities), showed convincingly how ‘cataclysmic’ money (money that arrives in huge amounts in short periods of time) is a surefire way of destroying all possibilities of improvement. What is needed, she argued, is ‘gradual’ money in the control of the residents themselves. While Jacobs was writing in the context of aid to impoverished communities within the US, she concluded with a remarkably prescient concern: “I hope we disburse foreign aid abroad more intelligently than we disburse it at home.”

Continue reading on Dawn.

For more on U.S. aid to Pakistan, see New Security Beat‘s coverage of the recent U.S.-Pakistani Strategic Dialogue.

Photo Credit: A U.S. Army Soldier with 32nd Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division, hands out medical supplies to Pakistani refugees outside an International Committee of the Red Crescent aid station in Afghanistan’s Kunar province, October 23, 2009. Courtesy of flickr user isafmedia. -

A Return to Rural Unrest in Nepal?

›July 27, 2010 // By Russell SticklorIn the four years since the end of Nepal’s civil war, political progress in creating a multi-party unity government in Kathmandu has moved in fits and starts. While the effort to bring the Maoists into the fold has made some headway since 2006, continuing environmental and economic troubles in the Nepalese countryside threaten to undermine these tentative steps.

In recent months, a new threat to political stability has emerged: the Sapta Kosi Multipurpose Project, a massive, India-backed hydropower scheme in eastern Nepal currently in the early stages of development. Once operational, the controversial dam—slated to reach a height of nearly 270 meters, making it one of the tallest dams in the world—is projected to generate 3,300 megawatts of electricity.

A proposed barrage and series of canals round out the project, enabling new irrigation and flood-control infrastructure in both eastern Nepal and the Indian state of Bihar, immediately to the south. But the potential environmental impacts of the mega-project have already sparked significant backlash among some Maoist-linked ethnic groups in the region, where the reach and influence of Nepal’s fledgling unity government is tenuous at best.

“Strong” Protests Threatened Over India-Backed Mega-Dam

In June, a network of 15 groups sympathetic to the Nepalese government’s Maoist wing warned of “strong” protests if survey work on the dam continued and “the voice of the indigenous people was not heard.” A memo released by the group dismissed the Sapta Kosi project as “anti-people.”

Specific criticisms of the project have ranged from safety concerns (the dam would be built in a seismically active region) to population displacement. Maoist leaders in the region have alleged that many villages—as well as important local religious sites and valuable agricultural land—could be flooded if the project goes forward. Other Maoists say the project should be delayed until Nepal is reorganized as a federal republic, at which point the states directly impacted by Sapta Kosi could be given greater control over the project.

Meanwhile, some objections to the project have targeted Nepal’s partnership with India. According to ShanghaiNews.net, members of the Maoist opposition have insinuated that hydropower from Sapta Kosi will not be consumed domestically, but rather exported to meet the needs of energy-hungry India.

A number of prominent Nepalese and Indian environmental activists have also spoken against the project, including Medha Patkar, a well-known activist who has played a major role in many past Indian anti-dam protests. Patkar warns the project will not mitigate but instead worsen seasonal flooding, calling plans for the joint India-Nepalese dam project “inauspicious from [an] environmental, cultural and religious point of view,” according to the Water & Energy Users’ Federation-Nepal.

As Nepal Pledges Security for Dam Project, India Pushes Forward

In the past, threats against the Sapta Kosi project have caused surveillance work in the area to be suspended repeatedly. But after the latest round of warnings, the Nepalese government adopted a different tactic, pledging heightened security in the region to ensure the safety of Indian officials doing fieldwork.

In doing so, Nepal’s coalition government is throwing its limited weight around, and—to a degree—staking its reputation on its ability to prevent an outbreak of violence. Historically, Nepal’s government has been largely bypassed or ignored in matters of hydroelectric development. As Nepal Water Conservation Foundation Director Dipak Gyawali told International Rivers in a June 2010 interview:The main players are private investors, with state entities and civil society unable to stand up to them….In Nepal, we just saw local politicians burn down the office of an international hydropower company even after the project was sanctioned by their leaders in the central government.

Gyawali added that during the Nepalese civil war (1996-2006), private developers were able to build “small hydropower projects even while a Maoist insurgency was raging because they did not ride roughshod over local concerns.” Regarding Sapta Kosi, Gyawali said the government should adopt a similar approach, and “start listening to the marginalized voices.” Otherwise, he warned, the Indian-Nepalese team spearheading the project “will be faced with delays, impasse, and intractable political problems,” including the potential for Maoist violence in the region. (As noted earlier this month in New Security Beat, the Indian government has also struggled with Maoist-linked violence in recent years, as New Delhi struggles to pacify a Naxalite insurgency in eastern and central India.)

Rural Nepal’s Troubles Far Bigger Than Sapta Kosi

Maoists may be wielding Sapta Kosi as a weapon to gain political leverage both in the countryside and Kathmandu, but the proposed dam is far from the only environmental issue impacting rural lives and threatening to undermine support for the central government.

In a country where firewood still accounts for 87 percent of annual domestic energy production, deforestation has been hugely problematic across rural Nepal. As of 2010, less than 30 percent of the country’s original forest-cover now remains. The rapid removal of forest cover has reduced soil quality, exacerbated seasonal flooding, and caused degraded water quality due to high sedimentation levels.

Further, as the country’s population grows at an annual rate of 2 percent, low soil productivity and unsustainable farming practices have turned Nepal’s effort to feed itself into a constant uphill struggle. According to the World Bank, the country sports one of the world’s highest ratios of population to available arable land, paving the way for potential further food shortages.

Sustainable energy development in Nepal perhaps represents one way of slowly restoring environmental health to the country. By investing in a more reliable national power grid, the central government could reduce rural dependence on firewood for fuel, allowing the country’s forests, soil, and waters to recover even as population increases. Further, hydroelectric projects like Sapta Kosi—implemented with greater involvement from local communities—could play an important role in moving the country forward. With an estimated untapped hydroelectric potential of 43,000 megawatts, Nepal could not only meet its own energy needs by developing its waterways, but profit from hydroelectric energy exports as well.

On the other hand, the Nepalese government could—at its own peril—continue to overlook rural populations’ grievances, and the environmental degradation unfolding outside Kathmandu. If left unchecked, however, these conditions could once again make the Maoist insurgency an appealing movement, potentially reviving grassroots support for anti-government extremism.

Sources: CIA, eKantipur.com (Nepal), International Rivers, Kathmandu Post, NepalNews.com, New York Times, ShanghaiNews.net, South Asia News Agency, Taragana.com, Thaindian News, Times of India, U.S. Energy Information Administration, WaterAid, Water & Energy Users Federation-Nepal, World Bank, World Wildlife Fund.

Photo Credit: “Neither in Nepal Nor India,” courtesy of Flickr user bodhithaj. -

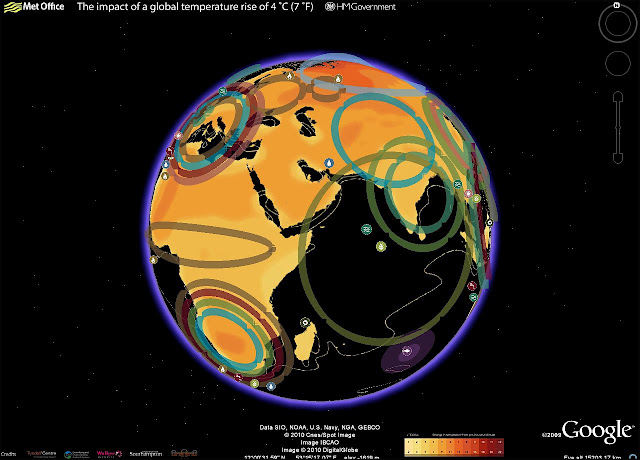

Rear Admiral Morisetti Launches the UK’s “4 Degree Map” on Google Earth

›Having had such success with the original “4 Degree Map” that the United Kingdom launched last October, my colleagues in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office have been working on a Google Earth version, which users can now download from the Foreign Office website.

This interactive map shows some of the possible impacts of a global temperature rise of 4 degrees Celsius (7° F). It underlines why the UK government and other countries believe we must keep global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial times; beyond that, the impacts will be increasingly disruptive to our global prosperity and security.

In my role as the UK’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy I have spoken to many colleagues in the international defense and security community about the threat climate change poses to our security. We need to understand how the impacts, as described in this map, will interact with other drivers of instability and global trends. Once we have this understanding we can then plan what needs to be done to mitigate the risks.

The map includes videos from the contributing scientists, who are led by the Met Office Hadley Centre. For example, if you click on the impact icon showing an increase in extreme weather events in the Gulf of Mexico region, up pops a video clip of the contributing scientist Dr Joanne Camp, talking about her research. It also includes examples of what the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and British Council are doing to increase people’s awareness of the risks climate change poses to our national security and prosperity, thus illustrating the FCO’s ongoing work on climate change and the low-carbon transition.

Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti is the United Kingdom’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy. -

Is the Third Pole the Next Site for Water Crisis?

›July 1, 2010 // By Tara InnesThe Hindu-Kush Himalaya area may host future water crises as glaciers melt, population rapidly increases, and competition over scarce water resources intensifies, says a recent report from the Humanitarian Futures Programme at King’s College.

Himalayan glaciers – often called the “third pole” because they house the greatest volume of frozen water outside the polar regions – provide the headwaters for 10 major river systems in Asia. Despite clear evidence that the HKH glaciers are receding, recent controversy over the 2007 IPCC report has sidetracked the discussion from the degree of glacial melt and its impacts on the surrounding environment.

Glacial melt sends more water into the rivers in the rainy season, and less water in the dry season. This variability will increase both floods and droughts, which in turn can damage agriculture and create food shortages. Melting glaciers can also create “glacial lakes” that are prone to sudden bursting, causing disastrous flooding downstream (ppt).

According to The Waters of the Third Pole: Sources of Threat, Sources of Survival, climate change is already having significant impacts in the Himalayan region, intensifying natural disasters and the variability of the summer monsoon rains, and increasing the number of displaced people and government attempts to secure water supplies from its neighbors.

Rivers of People: Environmental Migrants

One of the major consequences, the report argues, could be “growing numbers of environmental migrants,” which the authors define as “people moving away from drying or degraded farmland or fisheries, and the millions displaced by ever-larger dams and river-diversion projects”—and including the Chinese government’s forced “‘re-location of people from ecologically fragile regions.”

Today, about 30 million (15 percent) of the world’s migrants are from the Himalayan region, the report says, warning that “in the next decade, should river flows reduce significantly, migration out of irrigated areas could be massive.” But the authors acknowledge that reliable estimates are rare – a problem pointed out in The New Security Beat.

However, it is clear that the region’s population is growing and urbanizing rapidly: By 2025, one-half of all Asians will live in cities, whereas one generation ago, the figure was one in 10. This incredible shift, says the report, places “some of the greatest pressures on water through increased demand and pollution.”

Water War or Water Peace?

The Waters of the Third Pole warns that growing scarcity could “raise the risk of conflict in a region already fraught with cross-border tensions.” While interstate tensions over water have been minimal to date, they could potentially increase in areas where significant percentages of river flow originate outside of a country’s borders – in 2005 Bangladesh relied on trans-boundary water supplies for 91 percent of its river flow, Pakistan for 76 percent, and India for 34 percent. Intra-state conflict is also expected to increase. The report notes, “In China alone, it has been reported that domestic uprisings have continued to increase in protest about water management or water-quality issues.”

However, the water-conflict link remains shaky within the scholarly community. As Dabelko recently told Diane Rehm about the region, “There are prospects for tensions, but quite frankly, water is difficult to [obtain] through war. It’s hard to pick it up and take it home.”

The report points out some areas in which water may actually pose an opportunity for regional cooperation rather than conflict, such as developing knowledge-sharing networks like the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development. The presence of such networks may help establish channels of communication and aid in diffusing other cross-border tensions. But the authors caution that “environmental cooperation generally lags far behind economic cooperation in the HKH region.”

The report concludes that policymakers must move the region higher on the humanitarian agenda; construct a framework for action that includes non-intrusive international support; and more thoroughly address knowledge and communication gaps.

Photo Credit: “Annapurna ways, Nepal,” courtesy of flickr user rakustow. -

Deepwater Horizon Prompts DOD Relief Efforts, Questions About Energy Security

›May 6, 2010 // By Schuyler NullAs the crippled Deepwater Horizon oil rig continues to spew an estimated 210,000 gallons of crude oil a day into the Gulf of Mexico, the Department of Defense has been asked to bring its considerable resources to bear on what has become an increasingly more common mission – disaster relief.

British Petroleum has requested specialized military imaging software and remote operating systems that are unavailable on the commercial market in order to help track and contain the spill.

In addition, the Coast Guard has been coordinating efforts to burn off oil collecting on the ocean’s surface and thousands of National Guard units have been ordered to the Gulf coast to help erect barriers in a bid to halt what President Obama called “a massive and potentially unprecedented environmental disaster,” as the oil slick creeps towards the coast.

As shown by these calls and the ongoing earthquake relief effort in Haiti, the military’s ability to respond to large-scale, catastrophic natural (and manmade) disasters is currently considered unmatched. The first Air National Guard aircraft was on the ground in Haiti 23 hours after the earthquake first struck, and DOD’s Transportation Command was able to begin supporting USAID relief efforts almost immediately. The Department of Defense also spearheaded American relief efforts after the 2004 tsunami and played a critical role in providing aid and security in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

The Pentagon’s four-year strategic doctrine, the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), released earlier this year, predicts that such humanitarian missions will become a more common occurrence for America’s military, as the world grapples with the destabilizing effects of climate change, population growth, and competition over finite energy resources. Some experts see this expansion of the military’s portfolio as an essential part of a “hearts and minds” strategy, while others are critical of the military’s ability to navigate the difficulties of long-term reconstruction.

The QDR also highlights DOD’s efforts to reduce the need for oil – and thus deepwater oil rigs – in the first place.

The DOD as a whole is the largest consumer of energy in the United States, consuming a million gallons of petroleum every three days. In accordance with the QDR, Pentagon leaders have set an ambitious goal of procuring at least 25 percent of the military’s non-tactical energy requirement from renewable sources by 2025. The Air Force – by far the Pentagon’s largest consumer of petroleum – would like to acquire half of its domestic jet fuel requirement from alternative fuels by 2016 and successfully flight-tested a F/A-18 “Green Hornet” on Earth Day, using a blend of camelina oil and jet fuel.

At a speech at Andrews Air Force Base in March, President Obama lauded these efforts as key steps to moving beyond a petroleum-dependant economy. However, at the same event, he announced the expansion of off-shore drilling, in what some saw as a political bone thrown to conservatives. Since the Deepwater Horizon incident, the administration announced a temporary moratorium until the causes of the rig explosion and wellhead collapse have been investigated.

Cleo Paskal, associate fellow for the Energy, Environment, and Development Programme at Chatham House, warns that without paying adequate attention to the potential effects of a changing environment on energy infrastructure projects of the future – like the kind of off-shore drilling proposed for the Gulf and Eastern seaboard – such disasters may occur more frequently.

In an interview with ECSP last fall, Paskal pointed out that off-shore oil and gas platforms in the Gulf of Mexico were a prime example of how a changing environment – such as increased storm frequency and strength – can impact existing infrastructure. “Katrina and Rita destroyed over 400 platforms, as well as refining capacity onshore. That creates a global spike in energy prices apart from having to rebuild the infrastructure.”

The Department of Defense has demonstrated – in policy, with the QDR, and in action – that it can marshal its considerable resources in the service of renewable energy and disaster relief. But given the scope of today’s climate and energy challenges, it will take much more to solve these problems.

Photo Credit: “Deepwater Horizon,” courtesy of flickr user U.S. Coast Guard. U.S. Air Force Tech. Sgt. Joe Torba of the 910th Aircraft Maintenance Squadron, which specializes in aerial spray, prepares to dispatch aircraft to a Gulf staging area. -

Visualizing Natural Resources, Population, and Conflict

›Environmental problems that amplify regional security issues are often multifaceted, especially across national boundaries. Obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the natural resource, energy, and security issues facing a region is not fast or easy.

Fortunately, the Environment and Security Initiative (ENVSEC) has created highly informative, easy-to-understand maps depicting environmental, health, population, and security issues in critical regions.

Published with assistance from the United Nations GRID-Arendal, these maps offer policymakers and the public a snapshot of the complex topography of environmental security hotspots in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and the Southern Caucasus.

Some that caught our eye:

• Environmental Issues in the Northern Caspian Sea: Overlaying environmental areas and energy production zones, this map finds hydrocarbon pollution in sturgeon spawning grounds, seal habitats in oil and gas fields, and energy production centers and waste disposal sites in flood zones.

• Water Withdrawal and Availability in the Aral Sea Basin: Simple and direct, this combination map and graph contrasts water usage with availability in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan—which stand in stark comparison to the excess water resources of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

• Environment and Security Issues in Belarus: In addition to noting the parts of the country with poor water quality and potassium mining, the map also delineates wildfires that occurred in areas contaminated by the Chernobyl explosion, thus threatening downwind populations.

Maps: Illustrations courtesy of the Environment & Security Initiative. -

Too Much or Too Little? A Changing Climate in the Mekong and Ganges River Basins

›November 24, 2009 // By Dan Asin “I’m an optimist,” said Peter McCornick, director for water policy at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute, about the future of food and water security in the Ganges and Mekong river basins at the World Wildlife Fund’s recent two-day symposium on water and climate change (video). Although the basins are under threat not only from climate change, but also urbanization, industrialization, development, and population growth, he maintained there are solutions, “as long as we understand what is going on.”

“I’m an optimist,” said Peter McCornick, director for water policy at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute, about the future of food and water security in the Ganges and Mekong river basins at the World Wildlife Fund’s recent two-day symposium on water and climate change (video). Although the basins are under threat not only from climate change, but also urbanization, industrialization, development, and population growth, he maintained there are solutions, “as long as we understand what is going on.”

Whereas big-picture discussions of Asia’s glaciers and rivers often start and end with “fewer glaciers = less water,” McCornick argued that the connection is not so simple. Glacial melt “is particularly important in the Indus,” he said, but not so for the Ganges or Mekong.

“The Ganges is basically a monsoon-driven river,” said McCornick, and only 6.6 percent of the Mekong’s waters have glacial origins. Predicting the effects of climate change on monsoons is “extremely difficult.” Periods of heavy and light rains will be more pronounced in the Mekong, and how and when upstream dams will release water—a possibly more serious issue (video)—is unknown.

Food security will be impacted by shifting water supplies in the Ganges and Mekong. Within the Ganges basin, India’s population—already the region’s most water-stressed—could see its yearly water supplies drop by a third, from 1,506 m3 per person today to 1,060 m3 per person by 2025. “This is still a lot of water,” McCornick said, but water efficiency must undergo dramatic improvements if food supplies are to keep up with population growth.

In contrast, the Mekong could have too much water. Eighty-five percent of the Mekong delta, located in Vietnam, is under cultivation and its staple crop and principal food export, rice, is highly susceptible to flooding, which could increase due to extreme rain events, rising sea levels, or dam releases.

The Mekong basin is also the world’s largest freshwater fishery, but the effect of dams on the migratory pattern of the basin’s 1200-1700 fish species is still unknown. The industry is valued at $2-3 billion each year, said McCornick, and declining fish populations will not only harm local food security, but local livelihoods as well.

Adaptation strategies to cope with shifts in water supply brought about by climate change must be implemented by individuals at the local level, said McCornick, who urged that future adaptation research concentrate on sub-basins. Specific adaptation strategies to be explored include:- Flexible water management institutions

- Intelligent use of groundwater resources during times of stress

- Management of the entire water storage continuum—not just that stored in dams, but also water stored in soil moisture and miniature artificial ponds.

Photo: Top, Mekong River Delta; Bottom, Mekong River Delta post-floods from heavy rains. Courtesy NASA. -

Sustaining the Environment After Crisis and Conflict

›December 4, 2008 // By Rachel Weisshaar “Unfortunately, disasters are a growth industry,” said Anita Van Breda of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) at “Sustaining Natural Resources and Environmental Integrity During Response to Crisis and Conflict,” a November 12 meeting sponsored by the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program. But the impact of increased disasters on the environment is not a priority for first responders: According to Charles Kelly, an affiliate of the Benfield Hazard Research Centre at University College London, their perspective is, “How many lives is it going to save, and how much time is it going to take?” Environmentalists, who tend to think in terms of decades and generations, can find it difficult to communicate effectively with aid workers. “You give a 30-page report and it’s not going to be read, and there’s going to be no action,” said Kelly.

“Unfortunately, disasters are a growth industry,” said Anita Van Breda of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) at “Sustaining Natural Resources and Environmental Integrity During Response to Crisis and Conflict,” a November 12 meeting sponsored by the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program. But the impact of increased disasters on the environment is not a priority for first responders: According to Charles Kelly, an affiliate of the Benfield Hazard Research Centre at University College London, their perspective is, “How many lives is it going to save, and how much time is it going to take?” Environmentalists, who tend to think in terms of decades and generations, can find it difficult to communicate effectively with aid workers. “You give a 30-page report and it’s not going to be read, and there’s going to be no action,” said Kelly.

Showing posts from category flooding.

“Unfortunately, disasters are a growth industry,” said Anita Van Breda of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) at “

“Unfortunately, disasters are a growth industry,” said Anita Van Breda of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) at “