-

Development From the Bottom Up and the Top Down

›From Poverty to Power: How Active Citizens and Effective States Can Change the World, by Oxfam’s Duncan Green, is a very important book—one that should be read by everyone at the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and bilateral aid agencies. It combines a critique of current development policies and institutions with insights from community organizing and grassroots empowerment. Furthermore, it is comprehensive, covering not only aid but also politics, inequality, vulnerability, and reform of global governance structures. Finally, the book links the two critical components of the development equation: citizen participation and competent governance. The dichotomy between these two has always been a false one.

Green’s central message is that “development, and in particular efforts to tackle inequality, is best achieved through a combination of active citizens and effective states.” This should become part of the operational code of every development institution.

Green points out that “shocks and changes” can be important catalysts for reform. The current financial crisis is one of these shocks, and for our political leaders, it has made global governance a problem to be dealt with—as opposed to an issue too easily ignored. Just look at the recent G20 meeting. My colleagues and I spent a fair amount of time a decade ago designing and trying to sell leaders on an expanded summit to deal with the challenges of globalization. There were no takers. Yet this month we had a heads-of-state meeting that included leaders previously excluded from the G7.

No one really knows how long this crisis will last. But if leaders and their governments do not respond wisely and creatively, the human costs in both rich and poor countries will be immense. Leaders must understand that market forces left unregulated can ultimately prove destructive. This is the lesson of the struggle to regulate the U.S. national economy during the 19th century and of the period after World War I.

The financial crisis also provides an opportunity to raise fundamental questions about long-standing development policies. I strongly believe that the world, and particularly the United States, needs to adopt a new type of realpolitik—call it global realpolitik if you wish. For the United States, a global agenda should include:- An energy strategy that transitions to a less oil-dependent energy supply;

- A climate policy that recognizes one of the greatest threats to our well-being;

- A renewed emphasis on agriculture so that food production increases, particularly in poor countries;

- A health policy that deals with major health threats, old and new, and equips the world to deal with the next pandemic;

- An international effort to deal with failing states and internal conflicts; and

- A major emphasis on ending poverty.

In all of these areas, development promotion provides an important set of tools. No matter how good our intentions, we cannot accomplish these goals without competent partners: states with the capacity to manage their own affairs and cooperate on global problems—states in which rights and freedoms are guaranteed, and in which people feel they have a voice in the policies that affect them. International development is critical to helping foster such states.

I have two additional comments on From Poverty to Power. First, I think the section on aid could have been stronger. The aid “business” is in considerable disrepair, with simply too many donors trying to do too many things in too many places with too little coordination. There are many ways to make aid more effective, but they will not be easy to implement, and Green could have delved into the complexities a bit more.

Second, the book’s strength is also its weakness. It is nearly 500 pages long and has 792 endnotes! Fortunately, there are summaries in English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese available online—but there needs to be a version aimed specifically at policymakers. Imagine you had 10 minutes to brief President-Elect Obama on the key findings of the book. What would you tell him? For better or worse, in this town, your insights are only as good as your elevator speech.

John W. Sewell is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the former president of the Overseas Development Council. -

Population-Health-Environment Effort Launched in American Samoa

› The government of American Samoa has decided to boldly address the issue of rapid population growth, due to its potentially severe environmental impacts on the territory. Governor Togiola Tulafono’s Coral Reef Advisory Group, for which I work, has identified population pressure as the single largest threat to American Samoa’s coastal resources. This is an important finding because all of American Samoa’s population lives along the coast, and the entire territory is considered a coastal zone.

The government of American Samoa has decided to boldly address the issue of rapid population growth, due to its potentially severe environmental impacts on the territory. Governor Togiola Tulafono’s Coral Reef Advisory Group, for which I work, has identified population pressure as the single largest threat to American Samoa’s coastal resources. This is an important finding because all of American Samoa’s population lives along the coast, and the entire territory is considered a coastal zone.

The government recently hosted a Population Summit with more than 130 key stakeholders to discuss the problems and to devise collaborative solutions. Governor Tulafono opened the summit by stating that “resources are not finite—there are limits—and in an island setting as ours, the primary threat comes from people and how they behave responsibly in their use of land, water and air.” Participants developed a Population Declaration containing numerous policy initiatives, project proposals, and a recommendation to create a Population Commission. This declaration was presented to the legislature and Governor Tulafono for their consideration. American Samoa recently held elections, and the new government will be sworn in come January, at which point the working team I coordinate will be pressing the government to implement this important call to action.

Population-health-environment (PHE) activities are still in their infancy in American Samoa. However, we do have some projects underway. The most progress so far has been with local education and outreach efforts. I am working with one of our local environmental educators to develop PHE lesson plans and activities for local schools. We will be advertising these lesson plans in the local newspaper and informing teachers that our staff are available to come to their schools to introduce these issues. In addition, we are developing a number of PHE educational resources to distribute at schools we visit.

Family planning clinic staff and environmental educators have begun collaborating on a weekly radio series on the issue of rapid population growth. These discussions are raising the awareness of listeners and encouraging them to be good stewards of their health and their environment. In addition, a team of educators is planning the first annual World Population Day event here next year.

On the policy side, we are collaborating with the various agencies, planning departments, and staff from the Secretariat of the Pacific Community to develop a Territorial Population Policy. Once this is developed, American Samoa will be one of only three island states in the South Pacific with such a policy. This policy is still in the early stages of being written, but I am confident that a draft will be developed over the coming year.

Finally, American Samoa is ramping up its marine-protected-area efforts, especially the Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources’ community-based fisheries management program, which is an ideal venue for integrating population and environmental efforts. One of my main focus areas over the coming year will be looking at how I can connect the ongoing Department of Health activities with these programs. Although we are still in the early stages of addressing PHE issues in American Samoa, I am hoping to use the momentum from the recent summit to get us up to speed as quickly as possible.

Alyssa Edwards, a former ECSP intern, is the population pressure local action strategy coordinator with the Coral Reef Advisory Group in American Samoa.

Photo: Samoan schoolchildren play on a truck. Courtesy of Alyssa Edwards. -

Probing Population Growth Near Protected Areas

›Justin Brashares and George Wittemyer’s recent article in Science, “Accelerated Human Population Growth at Protected Area Edges,” presents data showing that average population growth at the edges of protected areas in Africa and Latin America is nearly double average rural population growth in the same countries. The authors argue that this phenomenon is due to migration, as people from surrounding areas are drawn to the health-care and livelihoods programs made available to people expelled from the parks.

It’s not news that high population growth rates have implications for conservation, both in terms of land-cover change and biodiversity loss. Yet at last month’s World Conservation Congress, I heard scarcely a mention of population growth or other demographic factors. So I appreciate that the authors are urging us to look at this aspect of conservation. In addition, by studying a large number of countries and protected areas, their work helps move our thinking beyond the inherent limitations of case studies focused on a single protected area.

I feel obligated to take issue with a few of the authors’ assumptions, methods, and conclusions, however. For instance, the authors compare growth rates for individual protected areas with national rural rates, and find the former are significantly higher in the vast majority of cases. I wonder why they don’t make the comparisons with the rural population growth rates for the region in which the protected area is located, since that seems as if it would make for an even more compelling argument.

My second issue is a note of caution regarding gridded population data. The creation of a gridded population layer depends both on the size of the population data units and the way in which the population is distributed. Given the inherent inaccuracies in this process at detailed levels of analysis, how can we be sure that the populations for the 10 km “buffer areas” surrounding the protected areas are accurate? Is there any way to validate these data, and how would errors impact the authors’ analysis? This issue is particularly important because rural areas tend to have large administrative units and sparse populations.

My third issue is with the authors’ examination of infant mortality rates as a proxy for poverty. The authors analyzed poverty in an attempt to determine whether poverty-driven population growth was informing their result; they concluded it was not. Measures of infant mortality are notoriously poor at the local level, and the authors need to go further in assessing what portion of growth is due to migration and what portion due to natural increase. While such an analysis would take time, it is necessary, given higher fertility in remote rural areas.

Despite my reservations about how the authors came to their conclusion, I tend to agree that migration is driving higher population growth in areas of high biodiversity and around protected areas. The reasons for migration, however, are diverse, and my fourth issue is that I don’t think the authors provide adequate evidence to demonstrate that conservation investments are driving migration to these areas. My three main reasons for taking issue with this finding:- The number of protected areas in the world has grown rapidly over the last 40 years, and they are generally located in sparsely populated areas. During this same period, the populations of most African and Latin American countries have doubled at least once. Thus, people have migrated to new frontiers—often near protected areas—seeking available agricultural land.

- Extractive industries—including timber, mining, oil and gas, and industrial agriculture—often provide lucrative jobs near protected areas. These jobs offer migrants far greater economic benefits than the meager amounts spent on conservation. Tourism is likely the only industry than can compete with these industries in attracting migrants, and only in areas with high numbers of visitors.

- The correlations the authors found between population growth and Global Environment Facility spending and population growth and protected area staff could, as the authors note, simply mean that conservationists are wisely spending their limited dollars on the protected areas facing the greatest threats.

Jason Bremner is program director of the Population Reference Bureau’s Population, Health, and Environment Program. -

Protecting the Soldier From the Environment and the Environment From the Soldier

›The end of the Cold War coincided with a decline in the total number of armed conflicts around the world; moreover, according to the UN Peacekeeping Capstone Doctrine, civil conflicts now outnumber interstate wars. These shifts have given rise to a new generation of peace support operations in which environmental issues are playing a growing role. The number of peace support operations launched by non-UN actors—including the EU and NATO—has doubled in the past decade.

The environment can harm deployed personnel through exposure to infectious diseases or environmental contaminants, so preventive measures are typically taken to protect the health of deployed forces. However, because environmental stress caused by climate change might act as a threat multiplier—increasing the need for peace support operations—it is ever more necessary for the international community to conduct crisis management operations in an environmentally sustainable fashion. But can the deployed soldier, police officer, or search-and-rescue worker really act as an environmental steward?

I believe important steps are being taken to ensure the answer to this question is “yes.” The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations recently drafted environmental protection policies and guidelines for UN field missions and started to implement them through the UN Department of Field Services and the UN Mission in Sudan. Various pilot projects are underway, including an environmental awareness and training program and sustainable base camp activities, such as alternative energy use. These projects are coordinated by the Swedish Defence Research Agency and funded by the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

Within NATO, Environmental Protection Standardization Agreements increase troop-contributing nations’ ability to work together on environmental protection. The NATO Science for Peace and Security Committee is also funding a set of workshops on the “Environmental Aspects of Military Compounds.”

Furthermore, defense organizations in Finland, Sweden, and the United States have cooperated to produce an Environmental Guidebook for Military Operations. The guidebook, which may be used by any nation, reflects a shared commitment to proactively reduce the environmental impacts of military operations and to protect the health and safety of deployed forces.

While the United Nations, NATO, and individual contributing nations are trying to reduce the environmental impact of their peacekeeping operations, the EU is lagging behind. In theory, the EU should find it easy to incorporate environmental considerations into its deployments. Most EU members are also NATO members, so if they can comply with NATO environmental regulations in NATO-led operations, they should be able to do the same with similar EU regulations in EU-led operations. Yet comparable regulations do not exist, even though the EU is often considered environmentally proactive—for instance, in its regulation of chemicals. Therefore, for the EU, it is indeed time to walk the walk—especially in light of its growing contribution to peace support operations, with recent operations conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Chad, and an upcoming intervention slated for Somalia.

Clearly, no single organization can conduct all of the multifaceted tasks required to support and consolidate the processes leading to a sustainable peace; partnerships between military and civilian actors are indispensable to achieving global stability. We must do a better job mainstreaming environmental considerations into foreign policy and into the operations of all stakeholders in post-conflict settings, with the understanding that the fallout from a fragile environment obeys no organizational boundaries. One small step in this direction is an upcoming NATO workshop, “Environmental Security Concerns prior to and during Peace Support and/or Crisis Management Operations.” If militaries continue to contribute to climate change and other forms of environmental degradation, they will be partially to blame when they are called in to defuse or clean up future conflicts over scarce, degraded, or rapidly changing resources.

Annica Waleij is a senior analyst and project manager at the Swedish Defence Research Agency’s Division of Chemical, Biological, Radioactive, and Nuclear Defence and Security. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Swedish Ministry of Defence. -

The Security Implications of Societies’ Demographic Growing Pains

› In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “The Battle of the (Youth) Bulge” (subscription required), Neil Howe and Richard Jackson take a critical look at the limits of the “youth bulge hypothesis,” which posits that a large and growing proportion of young adults puts societies at greater risk for political instability and civil conflict. The authors’ bigger target in this article is an assumption they perceive as widespread in the security community: that ongoing decline in youth bulges will necessarily produce what the authors dub a “demographic peace.” Howe and Jackson argue that such an expectation is overblown, and that’s clearly the case: Researchers, including myself, describe the effects of a declining youth bulge in terms of lowered risk of instability or conflict (see articles in ECSP Report 10 and ECSP Report 12). Its effects have never been proven absolute or inalterable.

In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “The Battle of the (Youth) Bulge” (subscription required), Neil Howe and Richard Jackson take a critical look at the limits of the “youth bulge hypothesis,” which posits that a large and growing proportion of young adults puts societies at greater risk for political instability and civil conflict. The authors’ bigger target in this article is an assumption they perceive as widespread in the security community: that ongoing decline in youth bulges will necessarily produce what the authors dub a “demographic peace.” Howe and Jackson argue that such an expectation is overblown, and that’s clearly the case: Researchers, including myself, describe the effects of a declining youth bulge in terms of lowered risk of instability or conflict (see articles in ECSP Report 10 and ECSP Report 12). Its effects have never been proven absolute or inalterable.

For me, Howe and Jackson’s strongest points lie in their identification of four complications that can arise at various points during the demographic transition:- Unsynchronized fertility decline among politically competitive ethnic groups, leading to shifts in ethnic composition;

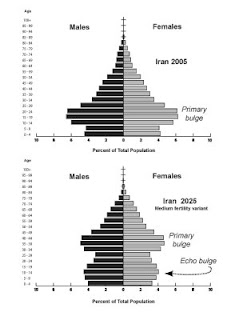

- Possible instabilities arising from a secondary youth bulge (an echo bulge), created as the previous generation’s bulge passes through its prime childbearing years (see figure);

- Questions about whether fertility can decline “too fast”; and

- The implications of continuous flows of foreign migrants into low-fertility countries—in particular, European countries today.

Some of Howe and Jackson’s other points seem muddled and inconsistent with quantitative studies, however. They cite researchers who argue that the mid-stages of economic development are the most threatening to security, and then link this to the demographic transition by declaring that “economic development…tend[s] to closely track demographic transition in each country.” This is mistaken: An extensive body of research informs demographers that economic development and fertility decline have been only weakly linked, even during the European fertility decline. While in several countries (including Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa) fertility declined abreast of rising per capita income, none of the East Asian “tigers” escaped the World Bank’s low-income country status until fertility dropped to near 3 children per woman, even though this measure had been declining steadily for years.

Nor can Howe and Jackson validate their assertion that having one of the middle structures is riskier than having one of the younger structures. Studies using the Uppsala Conflict Database’s record of minor and major conflicts show that, from 1970-1999, the very youngest countries (median age less than 18) and the middle group (median age 18-25) both experienced elevated risks of the emergence of a civil conflict —and both have large youth bulges. As Leahy and colleagues have shown, the youngest group was at greatest risk.

However, there is a way to salvage Howe and Jackson’s point. When infant mortality declines rapidly in the absence of fertility decline, age structures actually grow younger—in other words, some aspects of development push countries back into the youngest, most vulnerable category. If this is what the authors mean, they could have been clearer.

The authors go on to contend that neo-authoritarian regimes are likely to crop up among late-transition age structures. Here Howe and Jackson cede demography too much power over a state’s destiny. If one considers Deng Xiaoping the architect of China’s neo-authoritarian state, Lee Kwan Yew Singapore’s, Ali Khamenei Iran’s, and Hugo Chávez Venezuela’s, then this thesis has little empirical support. None of these regimes were established during the latter part of the demographic transition. Deng, Lee, and Ali Khamenei actually hastened fertility decline from high levels. I will, however, grant that Deng and Lee grew powerful as their countries’ age structures matured, and as that maturity promoted economic growth and reduced political tensions.

Overall, I’m much more positive than Howe and Jackson. I believe that parts of the world will, indeed, be left more politically stable and more democratic when very young age structures mature. Look at much of East Asia. Few veterans of conflicts in that region would have expected that, in 2008, most of its countries would be listed as vacation spots. I find it hard to believe, as Howe and Jackson do, that the most advanced phases of the demographic transition—a period yet to come—pose the greatest global security threats. Of course, I’m guessing…and so are they.

Richard Cincotta is the consulting demographer for the Long-Range Analysis Unit of the National Intelligence Council.

Figure: Iran’s 2005 youth bulge could give rise to an echo bulge in 2025. Courtesy of Richard Cincotta. -

Environment, Population in the 2008 National Defense Strategy

›The 2008 National Defense Strategy (NDS), released by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) earlier this summer, delivers the expected, but also throws in a few surprises. The NDS reflects traditional concerns over terrorism, rogue states, and the rise of China, but also gives a more prominent role to the connections among people, their environment, and national security. Both natural disasters and growing competition for resources are listed alongside terrorism as some of the main challenges facing the United States.

This NDS is groundbreaking in that it recognizes the security risks posed by both population growth and deficit—due to aging, shrinking, or disease—the role of climate pressures, and the connections between population and the environment. In the wake of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports on climate change and the CNA study on climate change and security, Congress mandated that the NDS include language on climate change. The document is required to include guidance for military planners to assess the risks of projected climate change on the armed forces (see Section 931 of the FY08 National Defense Authorization Act). The document also recognizes the need to address the “root causes of turmoil”—which could be interpreted as underlying population-environment connections, although the authors provide no specifics. One missed opportunity in the NDS is the chance to explicitly connect ungoverned areas in failed or weak states with population-environment issues.

What really stands out about this NDS is how the authors characterize the future security environment: “Over the next twenty years physical pressures—population, resource, energy, climatic and environmental—could combine with rapid social, cultural, technological and geopolitical change to create greater uncertainty,” they write. The challenge, according to DoD, is the uncertainty of how these trends and the interactions among them will play out. DoD is concerned with environmental security issues insofar as they shift the power of states and pose risks, but it is unclear from the NDS what precisely those risks are, as the authors never explicitly identify them. Instead, they emphasize flexibility in preparing to meet a range of possible challenges.

The environmental security language in this NDS grew out of several years of work within the Department, primarily in the Office of Policy Planning under the Office of the Under Secretary for Defense. The “Shocks and Trends” project carried out by Policy Planning involved several years of study on individual trends, such as population, energy, and environment, as well as a series of workshops and exercises outlining possible “shocks.” The impact of this work on the NDS is clear. For example, the NDS says “we must take account of the implications of demographic trends, particularly population growth in much of the developing world and the population deficit in much of the developed world.”

Finally, although the NDS mentions the goal of reducing fuel demand and the need to “assist wider U.S. Government energy security and environmental objectives,” its main energy concern seems to be securing access to energy resources, perhaps with military involvement. Is this another missed opportunity to bring in environmental concerns, or is it more appropriate for DoD to stick to straight energy security? The NDS seems to have taken a politically safe route: recognizing energy security as a problem and suggesting both the need for the Department to actively protect energy resources (especially petroleum) while also being open to broader ways to achieve energy independence.

According to the NDS, DoD should continue studying how the trends outlined above affect national security and should use trend considerations in decisions about equipment and capabilities; alliances and partnerships; and relationships with other nations. As the foundational document from which almost all other DoD guidance documents and programs are derived, the NDS is highly significant. If the new administration continues to build off of the current NDS instead of starting anew, we can expect environmental security to play a more central role in national defense planning. If not, environmental security could again take a back seat to other national defense issues, as it has done so often in the past.

Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba is the Mellon Environmental Fellow in the Department of International Studies at Rhodes College. She worked in the Office of Policy Planning as a demography consultant during the preparations for the 2008 NDS and continues to be affiliated with the office. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

For more information, see Sciubba’s article “Population in Defense Policy Planning” in ECSP Report 13. -

A Roadmap for Future U.S. International Water Policy

› When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have more than 15 government agencies with capacities to address water and sanitation issues abroad. And yes, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development published a joint strategic framework this year for action on water issues in the developing world.

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have more than 15 government agencies with capacities to address water and sanitation issues abroad. And yes, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development published a joint strategic framework this year for action on water issues in the developing world.

However, the U.S. government (USG) does not yet have an overarching strategy to guide our water programs abroad and maximize synergies among (and within) agencies. Furthermore, the 2005 Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act—which calls for increased water and sanitation assistance to developing countries—has yet to be funded and implemented in a fashion that satisfies lawmakers. In fact, just last week, legislation was introduced in both the House and the Senate to enhance the capacity of the USG to fully implement the Water for the Poor Act.

Why has implementation been so slow? An underlying problem is that water still has no institutional home in the USG, unlike other resources like agriculture and energy, which have entire departments devoted to them. In the current system, interagency water coordination falls on a small, under-resourced (yet incredibly talented and dedicated) team in the State Department comprised of individuals who must juggle competing priorities under the broad portfolio of Oceans, Environment, and Science. In part, it is water’s institutional homelessness that hinders interagency collaboration, as mandates and funding for addressing water issues are not always clearly delineated.

So, what should be done? For the last year and a half, the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Global Strategy Institute has consulted with policy experts, advocates, scientists, and practitioners to answer this million-dollar question. In our report, Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy, we conclude that if we are serious about achieving a range of our strategic national interests, water must be elevated as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. Water is paramount to human health, agricultural and energy production, education, economic development, post-conflict stabilization, and more—therefore, our government’s organizational structure and the resources it commits to water should reflect the strategic importance of this resource.

Studies’ (CSIS) Global Strategy Institute has consulted with policy experts, advocates, scientists, and practitioners to answer this million-dollar question. In our report, Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy, we conclude that if we are serious about achieving a range of our strategic national interests, water must be elevated as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. Water is paramount to human health, agricultural and energy production, education, economic development, post-conflict stabilization, and more—therefore, our government’s organizational structure and the resources it commits to water should reflect the strategic importance of this resource.

We propose the creation of a new bureau or “one-stop shop” for water policy in the State Department to lead in strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation of international water programs; mobilize resources in support of water programming overseas; provide outreach to Congress and important stakeholders; and serve as a research and information clearinghouse. This would require significant support from the highest levels of government, increased funding, and greater collaboration with the private and independent sectors.

The current economic crisis means we are likely to face even greater competition for scarce foreign aid resources. But I would argue—paraphrasing Congressman Earl Blumenauer at our report rollout—that relatively little funding toward water and sanitation can have a significant impact around the world. As we tighten our belts during this period of financial instability, it is even more important that we invest in cross-cutting issues that yield the highest returns across defense, development, and diplomacy. Water is an excellent place to start.

Rachel Posner is a research associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Global Strategy Institute.

Photo: Environmental Change and Security Program Director Geoff Dabelko and Congressman Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) at the launch of Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy. Courtesy of CSIS. -

Climate Change and Security

› Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”

Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”

From July 27-30, 2008, my organization, the Center for a New American Security, led a consortium of 10 scientific, private, and public policy organizations in an experiment to answer this particular “what if.” The experiment, a climate change “war game,” tested what a change in U.S. position might mean in 2015, when the effects of climate change will likely be more apparent and the global need to act will be more urgent. The participants were scientists, national security strategists, scholars, and members of the business community from China, Europe, India, and the Americas. The variety was intentional: We hoped to leverage a range of expertise and see how these different communities would interact to solve problems.

Climate change may seem a strange subject for a war game, but one of our primary goals was to highlight the ways in which global climate change is, in fact, a national security issue. In our view, climate change is highly likely to provoke conflict—within states, along borders as populations move, and, down the line, possibly between states. Also, the way the military calculates risk and engages in long-term planning lends itself to planning for the climate change that is already locked in (and gives strategic urgency to cutting emissions and preventing future climate change).

The players were asked to confront a near-term future in 2015, in which greenhouse gas emissions have continued to grow and the pattern of volatile and severe weather events has continued. The context of the game was an emergency ad-hoc meeting of the world’s top greenhouse gas emitters in 2015—China, the European Union, India, and the United States—to consider future projections (unlike most war games, the projections were real; Oak Ridge National Laboratory analyzed regional-level Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change data from the A1FI series specifically for the game). The “UN Secretary-General” challenged the top emitters to come up with an agreement to deal with increased migration resulting from climate change; resource scarcity; disaster relief; and drastic emissions cuts.

Although the players did reach an agreement, which is an interesting artifact in itself, that was not really the point. The primary objective was to see how the teams interacted and whether we gained any insight into our current situation. While we’re still processing all of our findings, I certainly came away with an interesting answer to that “what if” question. If the United States had been forward-leaning on climate change these past eight years, taking action at home and proposing change internationally, it would have made a difference, but only to a point. As important as American leadership will be on this issue, it is Chinese leadership—or followership—that will be decisive. And it is going to be very, very difficult—perhaps impossible—for China to lead, at least under current circumstances. The tremendous growth of China’s economy has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but there are hundreds of millions more still to be lifted. The stark reality is that China will be fueling that economic growth with coal, oil, and natural gas—just as the United States did in the 20th century—unless and until there is a viable alternative.

If the next administration hopes to head off the worst effects of global climate change, it will not only have to find a way to cut greenhouse gas emissions at home, it may well have to make it possible for China to do so, too.

Sharon Burke is a national security expert at the Center for a New American Security, where she focuses on energy, climate change, and the Middle East.

Photo: The U.S., EU, and Chinese simulation teams in negotiations. Courtesy of Sharon Burke.

Showing posts from category Guest Contributor.

The government of American Samoa has decided to boldly address the issue of rapid population growth, due to its potentially severe environmental impacts on the territory. Governor Togiola Tulafono’s

The government of American Samoa has decided to boldly address the issue of rapid population growth, due to its potentially severe environmental impacts on the territory. Governor Togiola Tulafono’s

In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “

In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “ When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have  Studies’ (CSIS)

Studies’ (CSIS)  Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”

Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”