-

Michael Kugelman, AfPak Channel

Pakistan’s Climate Change Challenge

›May 11, 2012 // By Wilson Center Staff

Last month, an avalanche on the Siachen glacier in Kashmir killed 124 Pakistani soldiers and 11 civilians. The tragedy has intensified debate about the logic of stationing Pakistani and Indian troops on such inhospitable terrain. And it has also brought attention to Pakistan’s environmental insecurity.

Siachen is rife with glacial melt; one study concludes the icy peak has retreated nearly two kilometers in less than 20 years. It has also been described as “the world’s highest waste dump.” Much of this waste-generated from soldiers’ food, fuel, and equipment-eventually finds its way to the Indus River Basin, Pakistan’s chief water source.

Siachen, in fact, serves as a microcosm of Pakistan’s environmental troubles. The nation experiences record-breaking temperatures, torrential rains (nearly 60 percent of Pakistan’s annual rainfall comes from monsoons), drought, and glacial melt (Pakistan’s United Nations representative, Hussain Haroon, contends that glacial recession on Pakistani mountains has increased by 23 percent over the past decade). Experts estimate that about a quarter of Pakistan’s land area and half of its population are vulnerable to climate change-related disasters, and several weeks ago Sindh’s environment minister said that millions of people across the province face “acute environmental threats.”

Continue reading on the AfPak Channel.

Sources: Daily Times, Dawn.com, Environment News Service, The Express Tribune, The New York Times, Remote Sensing Technology Center of Japan.

Photo Credit: “Surveying damage in Pakistan,” courtesy of the U.S. Army.

-

A Northern View: Canada’s Climate Claims and Obligations

›Reneging on Kyoto, Keystone pipeline drama, pain at the pump, re-aligned Arctic sovereignty, melting outdoor hockey rinks – all these aspects of climate change are being discussed in Canada.

However, Canadians, as potential citizens of the next energy superpower, need a more comprehensive and enriching debate. Climate change adaptation measures, at home and abroad, are inevitable, but the issue has largely been ignored by the federal government thus far.

To many Americans, it may seem that Canada has equated energy production with national prosperity, but Canadians are increasingly concerned about the human security and eco-justice implications of ongoing climate change as well. Lack of leadership at the federal level on Kyoto-related energy efficiency and emissions mitigation has been partially offset by actions at the provincial and municipal levels, but climate change is occurring now and it demands a coordinated response from the federal government, the only political apparatus capable of channeling the resources necessary for making a solid contribution to global climate change adaptation.

A moderate predictive scenario suggests that the regional impacts of climate change will be very expensive: the UN projects the global Green Climate Fund will require up to $100 billion a year by 2020. Water stress – too little, too much, or the perception of either – may be the most common theme. Coastal flooding, shoreline erosion, glacier retreat, chronic water shortages, loss of biodiversity and habitat, increased spread of invasive species, extreme weather events; taking preventive action against these (beyond the obvious call for reduced emissions) will be prohibitively expensive for most communities around the globe, including the coastal and northern regions of Canada.

The UN Convention to Combat Desertification has become a conduit for the argument that drought and land degradation related to climate change justifies southern demands for northern investment in initiatives in Africa and elsewhere. As a high emissions per capita nation, Canada has an obligation to contribute to such international efforts.

But I also don’t see why the indigenous peoples of the circumpolar north should be denied claims as permafrost thaws and ice-cover vital for subsistence hunting disappears. Citizens of small island states, to whom adaptation may well mean the abandonment of their homeland, have charged willful ignorance or purposeful negligence of their plight; so too might riparian communities along Canada’s many ocean shorelines, lakes, and rivers. Farmers, fishers, First Nations communities: all will need to adapt. We need to start seriously planning ahead to meet climate change scenarios, instead of burying the issue under the tar sands.

Of course, people will adapt to shifting conditions; such is the imperative of survival. And there are many ingenious ways this will materialize. Indeed many mitigation and adaptation strategies blend together as hybrids today. Building more effective alternative energy systems can be seen as much as responses to climate change as preventive measures and involve both public and private sector funding, for example.

However, paying for adaptation is another matter, and here it is vital in my view to stress the potential role of infrastructure spending by the federal government. Much of Canada’s current fiscal restraint is indeed a welcome development if the government cuts back on waste and redundancy, but not if it serves as a veil for sacrificing principles of eco-justice – the idea that those who made the least contributions to and benefit the least from environmental problems should not bear disproportionately higher risks.

Of course there will be nasty disputes ahead about the accounting, accountability, legitimacy, and purpose of climate change adaptation funding for Canada, in or out of the UNFCCC process, but let me draw just a few general conclusions at this stage:- There is an ethical imperative to contribute to international adaptation funding, perhaps just as great an imperative as traditional efforts to help former colonized countries. It’s not just about money, at least not directly: Canadian technical, policy, and financial expertise should be harnessed for this purpose as well.

- Unlike in other policy areas, there is no way to unload or pass the buck on climate change adaptation efforts: they demand the utilization of centralized resources redistributed throughout the country and through multilateral funding mechanisms.

- Adaptation funding should not, however, supplant more traditional emergency, humanitarian, or environmental funding. It should be seen as a supplement, albeit one with increasing importance, but not as a new form of dependency or gold-rush of aid-with-obligations opportunities. The current government is right to worry about accountability issues.

- But accountability goes both ways: we need at least to get the accounting and communications right on this, thus the need for open dialogue and ongoing consultation. Killing the well-respected National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy, which consulted various Canadian stakeholders on key environmental questions, was not a good start.

Peter Stoett is the Fulbright Research Chair in Canada-U.S. Relations at the Wilson Center’s Canada Institute and professor in the Department of Political Science at Concordia University, Montreal.

Sources: CBC, The Catholic Register, The Huffington Post, International Institute for Sustainable Development, UNFCCC.

Photo Credit: “City, Suburb, Ocean, Mountain,” courtesy of flickr user ecstaticist (Evan Leeson). -

Taming Hunger in Ethiopia: The Role of Population Dynamics

›May 4, 2012 // By Laurie Mazur

Ethiopia has been deemed a population-climate “hotspot” – a place where rapid growth and a changing climate pose grave threats to food security and human well-being.

-

Avoiding Adding Insult to Injury in Climate Adaptation Efforts

› Climate change is expected to produce winners and losers – for example, melting ice-caps may open up new economic opportunities for Greenland at the same time as sea-level rise threatens Asia’s bourgeoning coastal mega-cities. The same can be said about plans to address climate change, from both the mitigation and adaptation perspectives. A special issue of Global Environmental Change, “Adding Insult to Injury: Climate Change, Social Stratification, and the Inequalities of Intervention,” takes on this topic, with two case studies providing particularly compelling evidence.

Climate change is expected to produce winners and losers – for example, melting ice-caps may open up new economic opportunities for Greenland at the same time as sea-level rise threatens Asia’s bourgeoning coastal mega-cities. The same can be said about plans to address climate change, from both the mitigation and adaptation perspectives. A special issue of Global Environmental Change, “Adding Insult to Injury: Climate Change, Social Stratification, and the Inequalities of Intervention,” takes on this topic, with two case studies providing particularly compelling evidence.

Betsy Beymer-Farris and Thomas Bassett argue in their contribution, “The REDD Menace: Resurgent Protectionism in Tanzania’s Mangrove Forests,” that efforts to ensure REDD readiness in Tanzania have placed local communities at risk of forced evictions, shattered livelihoods, and persecution by both the state and conservation community. Contrary to dominant narratives that “portray local resources users, the Warufiji, in negative terms as recent migrants who are destroying the mangrove forests,” the authors say that they in fact depend upon “allow[ing] the mangroves to regenerate naturally while preparing new rice fields.” “To carbon traders, however, an uninhabited forest greatly simplifies the logistical tasks of monitoring and paying for ecosystem services,” assert the authors. This has resulted in declaration of local communities as squatters, illegally invading the forest. Government officials have repeatedly voiced threats of eviction. As well as increasing the potential for social tension, the study concludes that, “it is difficult to reconcile Tanzania REDD’s participatory and benefit sharing goals with the rhetoric, practices, and plans of the Tanzanian state.”

In “Accessing Adaptation: Multiple Stressors on Livelihoods in the Bolivian Highlands Under a Changing Climate,” Julia McDowell and Jeremy Hess present evidence about how specifically-tailored adaptations to climate change risk increasing vulnerability to a complex web of other, less obvious stressors. The study draws evidence from the livelihoods of historically marginalized indigenous farmers in highland Bolivia. The authors, who see “adaptation as part of ongoing livelihoods strategies,” use the case to “explore the tradeoffs that households make when adjustments to one stressor compromise the ability to adjust to another.” For instance, socio-economic stressors have forced many farmers to more closely couple their livelihoods with the market economy by growing more cash crops, intensifying land use, participating in off-farm laboring, and relying on irrigated agriculture. However, the shift to more market-orientated livelihoods has also increased their sensitivity to climatic stress. “As stressors compounded, the ability to mobilize assets became constrained, making adaptation choices highly interdependent, and sometimes contradictory,” the authors write. Avoiding these sorts of lose-lose situations, requires “ensuring sustained access to assets, rather than designing interventions solely to protect against a specific stressor.” -

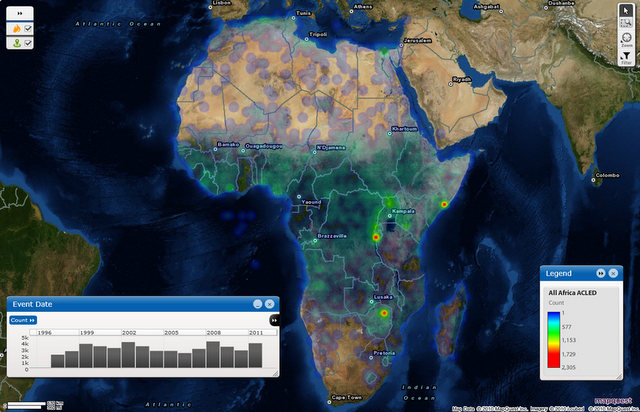

Updates to African Conflict Database Give Researchers Access to Comprehensive, Near Real-Time Information

›Despite the end of Cold War-era civil wars, political violence rates in Africa remain remarkably high. However, this broad statement hides an important qualification: the types of violence that have persisted in recent years have changed significantly, shifting from rebel and government activity towards violence against civilians, riots, protests, and battles by armed groups other than rebels.

The only way researchers can track this activity is through political violence data disaggregated by type, location, and time. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED) project aims to provide that service. We recently released updated information on political violence across Africa from January 1997 to December 2011 (see above for a hotspot map and timeline of violence over this period).

New to the ACLED project are real time data and trend reports on monthly conflict patterns throughout the continent. It is now perhaps the comprehensive and representative depiction of political violence as it occurs throughout Africa.

The data captures an array of actions including battles, looting, rioting, protesting, violence against civilians, and non-violent activity (such as arrests, recruitment drives, troop movements) by a variety of actors such as governments, rebels, militias, rioters and protestors.

Each event is geo-referenced by location and time-stamped by day. In our recently released version, we also included fatalities by event; distinguished conflict groups by their type (government, rebel, political militia, communal militia, rioters, protesters, civilians etc.); and specified the type of interaction between actors (e.g. government-rebel battle; rebel-civilian attack). These changes make ACLED data flexible for multiple uses.

Several new findings on conflict patterns are found using ACLED data:- Violence against civilians accounts for approximately half of all conflict events.

- Generally, where they occur, civil wars intensely affect 19 percent of a state’s territory, yet rebel actions have drastically decreased since 2005.

- Militia activity has significantly increased since 2005 and is especially high during election periods in new democracies.

- Communal violence patterns are more widespread but affect fewer people than civil war violence.

- Civil war patterns are not strongly affected by climate changes, but communal conflict decreases during periods of local scarcity and increases on the cusp of rainy seasons.

- Political violence increases in the period from peace talk announcements to negotiations. This violence is directed towards overtaking territory and civilians are frequently the main victims.

Fine-grained data on the range of political violence in the developing world is important as it provides the opportunity to ask and potentially answer certain questions about a range of issues related to governance, economic development, and conflict dynamics themselves.

For example, ACLED data shows that violence is increasingly occurring in villages, towns, and cities across Africa. In other words, political violence may be “urbanizing.” This has important implications for how we understand the practice of politics, the geography of marginalization, and the role of trigger patterns in explaining conflict. But there are many competing theories that could explain this trend.

Using data that disaggregates by violence type allows us to probe deeper: If the environmental security framework is correct, political violence in towns may be a response to high in-migration from rural areas to cities. Violence therefore is due to competition between urban people and migrant populations.

An alternative explanation is that the poor conditions of African urban life, high rates of informal employment, and under-representation of urban communities in government might explain an increase in violence. In this case, violence is a populist response, in that civilians riot and protest in favor of government reform.

Finally, the advantages of densely populated urban areas – easier access to resources, recruits, infrastructure, and power – may attract more organized groups to contest these spaces. If this explanation were correct, we would expect higher rates of rebel activity against government forces in cities, with a clear drive to overtaking the capital.

We have not been able to address these questions before with credible and comprehensive data, but now we can. Indeed, such data is crucial for interrogating the climate-security debate.

For example, Clionadh recently co-authored an article in the Journal of Peace Research’s special issue on climate and conflict, which used ACLED data for East Africa. In that piece, she and her co-author argued that different conflict groups use their environment in accordance with their overall goals. While much of the conflict activity studied had an environmental signal, the climate signal was much weaker.

We hope that these studies and other work with disaggregated data spur more theories and explanations of conflict patterns in developing states, and that the breadth and form of the data allows for new directions within conflict research.

Clionadh Raleigh is an assistant professor in the Department of Geography at Trinity College, Dublin, external researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), and director of the ACLED project. Caitriona Dowd of Trinity College and Andrew Linke of the University of Colorado are senior researchers for ACLED.

Image Credit: ACLED. -

Women’s Rights and Voices Belong at Rio+20

›This summer, world leaders will gather in Rio de Janeiro for the 20th anniversary of the first UN Earth Summit to hammer out a new set of agreements on what sustainable development means and, more importantly, how both rich and developing nations can get there before it’s too late. However, for the scores of women who will be attending (and just importantly for those who aren’t), there are glaring omissions: reproductive health, gender equality, and girls education are nowhere to be found on the Rio+20 agenda.

Women offer many of the most promising levers for the transformation to sustainable development. My experience with the Global Fund for Women tells me that women are full of creative and strategic solutions to the problems facing their communities around the world. Their voices must be included in critical decisions affecting our world. And the fact is, sustainable development isn’t sustainable if it doesn’t include empowering women to plan their families, educate themselves, and their children, and have a voice in government at all levels. Rio+20 must have human rights – and women’s rights – at its core. Earth summit planners haven’t yet done that, but women can make it happen.

Women are 51 percent of the world’s population, yet own only one percent of its assets, are two-thirds of the world’s workers but earn a mere 10 percent of wages. Rio+20 must not become another forum in which women’s issues are not heard. Instead, the summit must demonstrate that women’s voices are integral to all development. Environmental sustainability simply can’t happen without women’s inclusion.

For example, in West Africa, women make up 70 percent of workers in agriculture. In Burkina Faso, deforestation, water scarcity, and soil erosion show us that climate change is already impacting women farmers. Women tend to “sacrifice themselves” in order to care for their families – feeding themselves last. And women are most likely to suffer and die in environmental disasters – particularly in the Asian countries most at risk from climate change.

So how do we support women while supporting the environment that sustains us all?

Simply meeting women’s needs for family planning is one inexpensive and powerful development strategy with a host of environmental benefits. Over 200 million women around the world want the ability to choose the spacing and number of children but don’t have access to, or accurate information about, basic contraceptives like condoms, pills, and IUDs. One-hundred and seventy-nine nations already agree that meeting this need is a top priority, and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) reflect a goal of universal access to family planning as well.

Satisfying this demand would dramatically reduce maternal and child mortality and enhance human rights. What’s more, two recent studies show that a reduction of 8 to 15 percent of essential carbon emissions can be obtained by meeting women’s needs for family planning. This reduction would be equivalent to stopping all deforestation or increasing the world’s use of wind power fortyfold.

The Earth Summit presents a major opportunity to ensure that women’s needs and rights are given top priority in plans for sustainable development. In a time of multiple, interlinked human and environmental crises and a very tight funding environment, investing in women is a clear winner.

A greater understanding of the impact of environmental degradation, pollution, and climate change on women, coupled with solid public policy that respects and protects women’s reproductive rights, is essential to the “Sustainable Development Goals” that many believe will emerge from Rio+20 to replace the MDGs, which expire in 2015.

As the summit approaches, it’s time to reflect on why women’s full participation and inclusion is so important and call for world leaders to harness the power of women as we launch the era of sustainable development.

Musimbi Kanyoro is president and CEO of the Global Fund for Women, which advances women’s human rights by investing in women-led organizations worldwide.

Sources: Food and Agriculture Organization, Guttmacher Institute, Moreland et al. (2010), O’Neill et al. (2010), Princeton Environmental Institute, UN, UNEP, World Bank, World Health Organization.

Photo Credit: “Reokadia Nakaweesa Nalongo,” courtesy of Jason Taylor/Friends of Earth International. -

Loaded Dice and Human Health: Measuring the Impacts of Climate Change

›In a new article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), “Insights From Past Millennia Into Climatic Impacts on Human Health and Survival,” Anthony McMichael compares scientific literature that reconstructs past climates with epidemiological research and comes away with more than a dozen examples of the influence of climate on human health and survival. “Risks to health [as a result of climatic change] are neither widely nor fully recognized,” McMichael writes, but “weather extremes and climatic impacts on food yields, fresh water, infectious diseases, conflict, and displacement” have led to human suffering across the centuries. Some of the literature reviewed, for instance, links the Younger Dryas (a several centuries long period of cooling) to hunger in the Nile Valley between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago, climatic shifts that expanded the range of disease carrying rats and fleas to the “Black Death” during the mid-1400s, and unusually strong El Niño events to a series of late Victorian-era droughts during the late-1800s.

“Climate Variability and Climate Change: The New Climate Dice,” a working paper from James Hansen, Makiko Sato, and Reto Ruedy recently submitted to PNAS, uses surface air temperature analysis from the Goddard Institute for Space Studies to examine the impact of global warming on the frequency of extreme weather events. Using measurements from 1951 to 1980 as a baseline, the study finds, first, that the planet has warmed by around half of a degree Celsius since the reference period, and second, that the global area affected by “extreme anomalies” (exceeding three standard deviations from the mean climate) has increased by a factor greater than 10. Affecting approximately 10 percent of global land surface in the last several years, these anomalies, such as the droughts and heat waves observed in Texas in 2011, Moscow in 2010, and France in 2003, “almost certainly would not have occurred in the absence of the global warming,” according to the authors.

The study uses this new evidence about the impact of climate change to update the concept of climate change as a “loading of the climate dice.” Where, the “climate of 1951-1980 [is represented] by colored dice with two sides red for ‘hot,’ two side blue for ‘cold,’ and two sides white for near average temperature,” and the dice themselves represent the chance of observing variations on mean temperature. Under this metaphor, today’s climate is best approximated by a dice with four sides red, one blue, and one white, according to the study.

As for the future, the data suggest that with just one full degree of warming, anomalies three deviations beyond the mean will be the norm, and five deviations beyond the mean will become more likely (the latest IPCC projections suggest between 1.8 and 4.0 degrees Celsius are likely). In essence, the red side of the die are not only multiplying, but becoming much more extreme. To put this into scale, the Moscow 2010 heat wave, an event that exceeded the three deviations mark, coincided with a doubling of the death rate in the Russian capital. -

Karen Newman: Population and Sustainable Development Links Are Complex, Controversial, and Critical

›April 23, 2012 // By Kate Diamond“The one child family norm in China has fixed the global imagination around population to be around doing something which constricts people’s and women’s choices, rather than expands women’s possibilities to take control of their lives,” said Karen Newman, the coordinator for the UK-based Population and Sustainability Network. But contemporary population programs are about educating people on and providing access to voluntary reproductive, sexual, and maternal health services.

Newman spoke to ECSP, during the Planet Under Pressure conference this year, about family planning efforts and the connection between population dynamics and the environment.

“You have what I would describe as a sort of kaleidoscope of complexity” between climate change and population dynamics – not just growth, said Newman, but urbanization and migration.

For example, China recently overtook the United States as the world’s largest emitter of carbon, and although China has 1.3 billion people compared to the United States’ 310 million, population can hardly be credited as the most important driver for the country’s emissions. “How fair is it [to credit population growth] without in the same nanosecond saying, ‘but most of the carbon that was emitted in China was to manufacture the goods that will of course be consumed in the West?” said Newman.

“It makes it more difficult to say in a sound bite that ‘OK, population and sustainable development, it’s the same conversation,’ which I believe it to be.”

The Population and Sustainability Network, working through the Population and Climate Change Alliance, collaborates with international organizations from North America, Europe, Ethiopia, and Madagascar to support on-the-ground groups working on integrated population, health, and environment programming. These programs address environmental issues, like marine conservation and deforestation, while also providing reproductive health services, including different methods of contraception, diagnosis and treatment of sexually-transmitted diseases, antenatal and postnatal care, and emergency obstetric care.

“As a result of people wanting to place a distance between those coercive family planning programs in the ‘60s and the way that we do reproductive health now…because it’s such a large package, there is a sense that…this reproductive health thing is too much, we can’t really get ahold of this,” said Newman.

“What I think we need to do is keep people focused on the fact that these are women’s rights,” she said. “But we at the same time have to say ‘this is relevant if you care about sustainable development and the world’s non-renewable resources.’”

Sources: United Nations Population Division.

Showing posts from category climate change.