Showing posts from category *Blog Columns.

-

Weekly Reading

›Military leaders and climate experts gathered in Paris for a November 3-5 conference on the role of the military in combating climate change. A conference report will include “proven strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while improving military effectiveness.”

The 2008 Africa Population Data Sheet, a joint project of the Population Reference Bureau and the African Population and Health Research Center, reveals significant differences between northern and sub-Saharan Africa. Also from PRB, “Reproductive Health in Sub-Saharan Africa” examines family planning use, family size, maternal mortality, and HIV/AIDS in major subregions of sub-Saharan Africa.

In the October 2008 issue of Humanitarian Exchange Magazine, Alexander Tyler of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees for Somalia argues that longer-term livelihoods projects must be incorporated into emergency humanitarian relief efforts. The authors of the Center for American Progress report The Cost of Reaction: The Long-Term Costs of Short-Term Cures (reviewed on the New Security Beat) would likely agree; they argue that although emergency aid is necessary, “what is true in our own lives is true on the international stage—an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The Dining & Wine section of the New York Times profiles a Quichua community in the Ecuadorian Amazon that has formed a successful chocolate cooperative with the help of a volunteer for a biodiversity foundation. “They wanted to find a way to survive and thrive as they faced pressure from companies that sought to log their hardwood trees, drill on their land for oil and mine for gold,” reports the Times. -

Probing Population Growth Near Protected Areas

›Justin Brashares and George Wittemyer’s recent article in Science, “Accelerated Human Population Growth at Protected Area Edges,” presents data showing that average population growth at the edges of protected areas in Africa and Latin America is nearly double average rural population growth in the same countries. The authors argue that this phenomenon is due to migration, as people from surrounding areas are drawn to the health-care and livelihoods programs made available to people expelled from the parks.

It’s not news that high population growth rates have implications for conservation, both in terms of land-cover change and biodiversity loss. Yet at last month’s World Conservation Congress, I heard scarcely a mention of population growth or other demographic factors. So I appreciate that the authors are urging us to look at this aspect of conservation. In addition, by studying a large number of countries and protected areas, their work helps move our thinking beyond the inherent limitations of case studies focused on a single protected area.

I feel obligated to take issue with a few of the authors’ assumptions, methods, and conclusions, however. For instance, the authors compare growth rates for individual protected areas with national rural rates, and find the former are significantly higher in the vast majority of cases. I wonder why they don’t make the comparisons with the rural population growth rates for the region in which the protected area is located, since that seems as if it would make for an even more compelling argument.

My second issue is a note of caution regarding gridded population data. The creation of a gridded population layer depends both on the size of the population data units and the way in which the population is distributed. Given the inherent inaccuracies in this process at detailed levels of analysis, how can we be sure that the populations for the 10 km “buffer areas” surrounding the protected areas are accurate? Is there any way to validate these data, and how would errors impact the authors’ analysis? This issue is particularly important because rural areas tend to have large administrative units and sparse populations.

My third issue is with the authors’ examination of infant mortality rates as a proxy for poverty. The authors analyzed poverty in an attempt to determine whether poverty-driven population growth was informing their result; they concluded it was not. Measures of infant mortality are notoriously poor at the local level, and the authors need to go further in assessing what portion of growth is due to migration and what portion due to natural increase. While such an analysis would take time, it is necessary, given higher fertility in remote rural areas.

Despite my reservations about how the authors came to their conclusion, I tend to agree that migration is driving higher population growth in areas of high biodiversity and around protected areas. The reasons for migration, however, are diverse, and my fourth issue is that I don’t think the authors provide adequate evidence to demonstrate that conservation investments are driving migration to these areas. My three main reasons for taking issue with this finding:- The number of protected areas in the world has grown rapidly over the last 40 years, and they are generally located in sparsely populated areas. During this same period, the populations of most African and Latin American countries have doubled at least once. Thus, people have migrated to new frontiers—often near protected areas—seeking available agricultural land.

- Extractive industries—including timber, mining, oil and gas, and industrial agriculture—often provide lucrative jobs near protected areas. These jobs offer migrants far greater economic benefits than the meager amounts spent on conservation. Tourism is likely the only industry than can compete with these industries in attracting migrants, and only in areas with high numbers of visitors.

- The correlations the authors found between population growth and Global Environment Facility spending and population growth and protected area staff could, as the authors note, simply mean that conservationists are wisely spending their limited dollars on the protected areas facing the greatest threats.

Jason Bremner is program director of the Population Reference Bureau’s Population, Health, and Environment Program. -

Weekly Reading

›In “Who Cares About the Weather?: Climate Change and U.S. National Security” (subscription required), Joshua Busby argues that although advocates have overstated some of climate change’s impacts, it nevertheless poses direct threats to conventional U.S. national security interests, and therefore deserves serious consideration by both academics and policymakers.

An article in the Economist examines the melting Kolahoi glacier, which could soon threaten water supply and livelihoods in the Kashmir valley.

“Marauding elephants in northern Uganda have added to the challenges faced by civilians trying to rebuild their lives in the wake of 20 years of civil war, destroying their crops and prompting some to return to displaced people’s (IDP) camps they had only recently left,” says an article from IRIN News.

In an EarthSky podcast interview, Lori Hunter of the University of Colorado, Boulder, discusses her work researching how HIV/AIDS affects families’ use of natural resources.

Payson Schwin of the World Resources Institute recently interviewed Crispino Lobo of the Watershed Organization Trust about his work helping rural Indian villages escape poverty by managing their natural resources sustainably.

A research commentary from Population Action International explores family planning trends in Pakistan, as well as the relationships between demography and security in this critically important country.

Despite—or perhaps because of—its extremely high population density, Rwanda has launched a series of initiatives to protect its environment and reduce poverty, reports the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

The Population Reference Bureau has released two new policy briefs examining population, health, and environment issues in Calabarzon Region and the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao.

Stalled Youth Transitions in the Middle East: A Framework for Policy Reform proposes changes to education, employment, and housing that would offer Middle Eastern youth additional opportunities. “Young people in the Middle East (15-29 years old) constitute about one-third of the region’s population, and growth rates for this age group are the second highest after sub-Saharan Africa,” say the authors. “Today, as the Middle East experiences a demographic boom along with an oil boom, the region faces a historic opportunity to capitalize on these twin dividends for lasting economic development.”

An October 2008 brief from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs uses examples from Africa and Latin America to explore ways to ensure that non-renewable resource revenues contribute to sustainable development.

Video is now available for “Breaking Barriers: Family Planning, Human Health and Conservation,” a session at this month’s Conservation Learning Exchange conference in Vancouver. -

Weekly Reading

›“[T]he careful management that helped make Alaskan pollock a billion-dollar industry could unravel as the planet warms,” warns Kenneth Weiss of the Los Angeles Times. “Pollock and other fish in the Bering Sea are moving to higher latitudes as winter ice retreats and water temperatures rise. Alaskan pollock are becoming Russian pollock, swimming across an international boundary in search of food and setting off what could become a geopolitical dispute.”

Poor rains, lack of infrastructure, and a shortage of skilled technicians have contributed to water-related disease and local-level water conflicts in Zimbabwe, reports IPS News.

If the Tripa peat forests in Sumatra continue to be cleared to make way for palm oil plantations, not only will the habitat of the critically endangered Sumatran orangutan shrink further, but millions of tons of CO2 will be released into the atmosphere, accelerating global climate change, reports the Telegraph.

A report on Somalia by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization says that one in six Somali children under the age of five is acutely malnourished and estimates that 43 percent of the country’s population will need humanitarian assistance through the end of the year. According to the report, poor rains, in addition to the worst levels of violence since 1990, have contributed to the humanitarian crisis.

“The number of tiger attacks on people is growing in India’s Sundarban islands as habitat loss and dwindling prey caused by climate change drives them to prowl into villages for food,” says an article from Reuters.

The current issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (some abstracts available) focuses on the links between climate change and public health.

“Can Conservation Succeed with 9 Billion People?,” a panel at the recent Conservation Learning Exchange, was described as a “bang-up session” by Margaret Francis, who blogged about it. -

Weekly Reading

›In an open letter on water policy to the next U.S. president, Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute urges the next presidential administration to develop a national water policy; highlight national security issues related to water; expand the United States’ role in addressing global water problems; and integrate climate change into all federal planning and activity on water.

A recent survey conducted by Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that land disputes are a key threat to peace in Liberia, reports BBC News.

Mikhail Gorbachev, former president of the former Soviet Union, called for a global glasnost, or openness, on environmental problems. “This financial turmoil, which will heavily affect the real economy, was absolutely predictable, and it is only one aspect of the wider crisis of all the current development systems,” said Gorbachev. “In fact, there are connected simultaneous crises that are rapidly emerging. These relate to energy, water, food, demography, climate change and the ecosystem devastation.”

The World Health Organization has developed a plan for research on the health impacts of climate change, reports the Science and Development Network. -

Protecting the Soldier From the Environment and the Environment From the Soldier

›The end of the Cold War coincided with a decline in the total number of armed conflicts around the world; moreover, according to the UN Peacekeeping Capstone Doctrine, civil conflicts now outnumber interstate wars. These shifts have given rise to a new generation of peace support operations in which environmental issues are playing a growing role. The number of peace support operations launched by non-UN actors—including the EU and NATO—has doubled in the past decade.

The environment can harm deployed personnel through exposure to infectious diseases or environmental contaminants, so preventive measures are typically taken to protect the health of deployed forces. However, because environmental stress caused by climate change might act as a threat multiplier—increasing the need for peace support operations—it is ever more necessary for the international community to conduct crisis management operations in an environmentally sustainable fashion. But can the deployed soldier, police officer, or search-and-rescue worker really act as an environmental steward?

I believe important steps are being taken to ensure the answer to this question is “yes.” The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations recently drafted environmental protection policies and guidelines for UN field missions and started to implement them through the UN Department of Field Services and the UN Mission in Sudan. Various pilot projects are underway, including an environmental awareness and training program and sustainable base camp activities, such as alternative energy use. These projects are coordinated by the Swedish Defence Research Agency and funded by the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

Within NATO, Environmental Protection Standardization Agreements increase troop-contributing nations’ ability to work together on environmental protection. The NATO Science for Peace and Security Committee is also funding a set of workshops on the “Environmental Aspects of Military Compounds.”

Furthermore, defense organizations in Finland, Sweden, and the United States have cooperated to produce an Environmental Guidebook for Military Operations. The guidebook, which may be used by any nation, reflects a shared commitment to proactively reduce the environmental impacts of military operations and to protect the health and safety of deployed forces.

While the United Nations, NATO, and individual contributing nations are trying to reduce the environmental impact of their peacekeeping operations, the EU is lagging behind. In theory, the EU should find it easy to incorporate environmental considerations into its deployments. Most EU members are also NATO members, so if they can comply with NATO environmental regulations in NATO-led operations, they should be able to do the same with similar EU regulations in EU-led operations. Yet comparable regulations do not exist, even though the EU is often considered environmentally proactive—for instance, in its regulation of chemicals. Therefore, for the EU, it is indeed time to walk the walk—especially in light of its growing contribution to peace support operations, with recent operations conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Chad, and an upcoming intervention slated for Somalia.

Clearly, no single organization can conduct all of the multifaceted tasks required to support and consolidate the processes leading to a sustainable peace; partnerships between military and civilian actors are indispensable to achieving global stability. We must do a better job mainstreaming environmental considerations into foreign policy and into the operations of all stakeholders in post-conflict settings, with the understanding that the fallout from a fragile environment obeys no organizational boundaries. One small step in this direction is an upcoming NATO workshop, “Environmental Security Concerns prior to and during Peace Support and/or Crisis Management Operations.” If militaries continue to contribute to climate change and other forms of environmental degradation, they will be partially to blame when they are called in to defuse or clean up future conflicts over scarce, degraded, or rapidly changing resources.

Annica Waleij is a senior analyst and project manager at the Swedish Defence Research Agency’s Division of Chemical, Biological, Radioactive, and Nuclear Defence and Security. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Swedish Ministry of Defence. -

The Security Implications of Societies’ Demographic Growing Pains

› In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “The Battle of the (Youth) Bulge” (subscription required), Neil Howe and Richard Jackson take a critical look at the limits of the “youth bulge hypothesis,” which posits that a large and growing proportion of young adults puts societies at greater risk for political instability and civil conflict. The authors’ bigger target in this article is an assumption they perceive as widespread in the security community: that ongoing decline in youth bulges will necessarily produce what the authors dub a “demographic peace.” Howe and Jackson argue that such an expectation is overblown, and that’s clearly the case: Researchers, including myself, describe the effects of a declining youth bulge in terms of lowered risk of instability or conflict (see articles in ECSP Report 10 and ECSP Report 12). Its effects have never been proven absolute or inalterable.

In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “The Battle of the (Youth) Bulge” (subscription required), Neil Howe and Richard Jackson take a critical look at the limits of the “youth bulge hypothesis,” which posits that a large and growing proportion of young adults puts societies at greater risk for political instability and civil conflict. The authors’ bigger target in this article is an assumption they perceive as widespread in the security community: that ongoing decline in youth bulges will necessarily produce what the authors dub a “demographic peace.” Howe and Jackson argue that such an expectation is overblown, and that’s clearly the case: Researchers, including myself, describe the effects of a declining youth bulge in terms of lowered risk of instability or conflict (see articles in ECSP Report 10 and ECSP Report 12). Its effects have never been proven absolute or inalterable.

For me, Howe and Jackson’s strongest points lie in their identification of four complications that can arise at various points during the demographic transition:- Unsynchronized fertility decline among politically competitive ethnic groups, leading to shifts in ethnic composition;

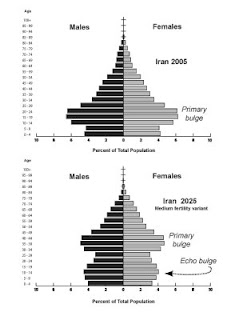

- Possible instabilities arising from a secondary youth bulge (an echo bulge), created as the previous generation’s bulge passes through its prime childbearing years (see figure);

- Questions about whether fertility can decline “too fast”; and

- The implications of continuous flows of foreign migrants into low-fertility countries—in particular, European countries today.

Some of Howe and Jackson’s other points seem muddled and inconsistent with quantitative studies, however. They cite researchers who argue that the mid-stages of economic development are the most threatening to security, and then link this to the demographic transition by declaring that “economic development…tend[s] to closely track demographic transition in each country.” This is mistaken: An extensive body of research informs demographers that economic development and fertility decline have been only weakly linked, even during the European fertility decline. While in several countries (including Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa) fertility declined abreast of rising per capita income, none of the East Asian “tigers” escaped the World Bank’s low-income country status until fertility dropped to near 3 children per woman, even though this measure had been declining steadily for years.

Nor can Howe and Jackson validate their assertion that having one of the middle structures is riskier than having one of the younger structures. Studies using the Uppsala Conflict Database’s record of minor and major conflicts show that, from 1970-1999, the very youngest countries (median age less than 18) and the middle group (median age 18-25) both experienced elevated risks of the emergence of a civil conflict —and both have large youth bulges. As Leahy and colleagues have shown, the youngest group was at greatest risk.

However, there is a way to salvage Howe and Jackson’s point. When infant mortality declines rapidly in the absence of fertility decline, age structures actually grow younger—in other words, some aspects of development push countries back into the youngest, most vulnerable category. If this is what the authors mean, they could have been clearer.

The authors go on to contend that neo-authoritarian regimes are likely to crop up among late-transition age structures. Here Howe and Jackson cede demography too much power over a state’s destiny. If one considers Deng Xiaoping the architect of China’s neo-authoritarian state, Lee Kwan Yew Singapore’s, Ali Khamenei Iran’s, and Hugo Chávez Venezuela’s, then this thesis has little empirical support. None of these regimes were established during the latter part of the demographic transition. Deng, Lee, and Ali Khamenei actually hastened fertility decline from high levels. I will, however, grant that Deng and Lee grew powerful as their countries’ age structures matured, and as that maturity promoted economic growth and reduced political tensions.

Overall, I’m much more positive than Howe and Jackson. I believe that parts of the world will, indeed, be left more politically stable and more democratic when very young age structures mature. Look at much of East Asia. Few veterans of conflicts in that region would have expected that, in 2008, most of its countries would be listed as vacation spots. I find it hard to believe, as Howe and Jackson do, that the most advanced phases of the demographic transition—a period yet to come—pose the greatest global security threats. Of course, I’m guessing…and so are they.

Richard Cincotta is the consulting demographer for the Long-Range Analysis Unit of the National Intelligence Council.

Figure: Iran’s 2005 youth bulge could give rise to an echo bulge in 2025. Courtesy of Richard Cincotta. -

Environment, Population in the 2008 National Defense Strategy

›The 2008 National Defense Strategy (NDS), released by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) earlier this summer, delivers the expected, but also throws in a few surprises. The NDS reflects traditional concerns over terrorism, rogue states, and the rise of China, but also gives a more prominent role to the connections among people, their environment, and national security. Both natural disasters and growing competition for resources are listed alongside terrorism as some of the main challenges facing the United States.

This NDS is groundbreaking in that it recognizes the security risks posed by both population growth and deficit—due to aging, shrinking, or disease—the role of climate pressures, and the connections between population and the environment. In the wake of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports on climate change and the CNA study on climate change and security, Congress mandated that the NDS include language on climate change. The document is required to include guidance for military planners to assess the risks of projected climate change on the armed forces (see Section 931 of the FY08 National Defense Authorization Act). The document also recognizes the need to address the “root causes of turmoil”—which could be interpreted as underlying population-environment connections, although the authors provide no specifics. One missed opportunity in the NDS is the chance to explicitly connect ungoverned areas in failed or weak states with population-environment issues.

What really stands out about this NDS is how the authors characterize the future security environment: “Over the next twenty years physical pressures—population, resource, energy, climatic and environmental—could combine with rapid social, cultural, technological and geopolitical change to create greater uncertainty,” they write. The challenge, according to DoD, is the uncertainty of how these trends and the interactions among them will play out. DoD is concerned with environmental security issues insofar as they shift the power of states and pose risks, but it is unclear from the NDS what precisely those risks are, as the authors never explicitly identify them. Instead, they emphasize flexibility in preparing to meet a range of possible challenges.

The environmental security language in this NDS grew out of several years of work within the Department, primarily in the Office of Policy Planning under the Office of the Under Secretary for Defense. The “Shocks and Trends” project carried out by Policy Planning involved several years of study on individual trends, such as population, energy, and environment, as well as a series of workshops and exercises outlining possible “shocks.” The impact of this work on the NDS is clear. For example, the NDS says “we must take account of the implications of demographic trends, particularly population growth in much of the developing world and the population deficit in much of the developed world.”

Finally, although the NDS mentions the goal of reducing fuel demand and the need to “assist wider U.S. Government energy security and environmental objectives,” its main energy concern seems to be securing access to energy resources, perhaps with military involvement. Is this another missed opportunity to bring in environmental concerns, or is it more appropriate for DoD to stick to straight energy security? The NDS seems to have taken a politically safe route: recognizing energy security as a problem and suggesting both the need for the Department to actively protect energy resources (especially petroleum) while also being open to broader ways to achieve energy independence.

According to the NDS, DoD should continue studying how the trends outlined above affect national security and should use trend considerations in decisions about equipment and capabilities; alliances and partnerships; and relationships with other nations. As the foundational document from which almost all other DoD guidance documents and programs are derived, the NDS is highly significant. If the new administration continues to build off of the current NDS instead of starting anew, we can expect environmental security to play a more central role in national defense planning. If not, environmental security could again take a back seat to other national defense issues, as it has done so often in the past.

Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba is the Mellon Environmental Fellow in the Department of International Studies at Rhodes College. She worked in the Office of Policy Planning as a demography consultant during the preparations for the 2008 NDS and continues to be affiliated with the office. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

For more information, see Sciubba’s article “Population in Defense Policy Planning” in ECSP Report 13.

In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “

In their provocative article in The National Interest entitled “