Showing posts from category *Blog Columns.

-

UN Security Council Debates Climate Change

› Today the UN Security Council is debating climate change and its links to peace and international security. In this short video, ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko outlines his hopes for today’s session and its follow-on activities. He suggests it is time to move from problem identification to problem solving by developing practical steps to respond to climate-security links.

Today the UN Security Council is debating climate change and its links to peace and international security. In this short video, ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko outlines his hopes for today’s session and its follow-on activities. He suggests it is time to move from problem identification to problem solving by developing practical steps to respond to climate-security links.

This Security Council debate was held at the instigation of the German government, chair of the Security Council this month. But it is not the first time this body has debated climate and security. In 2007, the United Kingdom used its prerogative as chair to introduce the topic in the security forum. Opinions from member states diverged on whether the Security Council was the appropriate venue for climate change.

Largely at the instigation of the Alliance of Small Island States, the UN General Assembly tackled climate and security links in 2009. The resulting resolution also spurred the UN Secretary-General to produce a summary report on the range of climate and security links.

Sources: Reuters, UN. -

Failed States Index 2011

›“The reasons for state weakness and failure are complex, but not unpredictable,” said J.J. Messner, one of the founders of the Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index, at the launch of the 2011 version of report in Washington last month. The Index is an analytical tool that could aid policymakers and governments seeking to prevent and mitigate state collapse by identifying patterns of underlying drivers of state instability.

The Index ranks 177 countries according to 12 primary social, economic, and political indicators based on analysis of “thousands of news and information sources and millions of documents” and distilled into a form that is meant to be “relevant as well as easily digestible and informative,” according to the creators. “By highlighting pertinent issues in weak and failing states,” they write, the Index “makes political risk assessment and early warning of conflict accessible to policymakers and the public at large.”

Common Threats: Demographic and Natural Resource Pressures

The Index reveals that half of the 10-most fragile states are acutely demographically challenged. The composite “Demographic Pressures” category takes into account population density, growth, and distribution; land and resource competition; water scarcity; food security; the impact of natural disasters; and public health prevention and control. Additional population indices are found in “Massive Movement of Refugees or Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs),” and health indicators, including infant mortality, water, and sanitation, are spread across several categories.

Not surprisingly, some of the most conflict-ridden countries show up at the top of the list. The Index highlights some of the lesser known issues that contribute to their misery: demographic and natural resource stresses in Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen (a list that would include Palestine, if inclusion in the Index were not contingent on UN membership); the DRC’s conflict minerals; and Somalia and Sudan’s myriad of environmental and migration problems, which play major roles in their continued instability.

Haiti, with its poor health and lack of infrastructure and disaster resilience, was deemed the Index’s “most-worsened” state of 2011. The January 2010 earthquake and its ensuing “chaos and humanitarian catastrophe” demonstrated that a single event can trigger the collapse of virtually every other sector of society, causing what Messner termed the “Humpty Dumpty effect” – while a state can deteriorate quickly, it is much harder to put it back together again.

The inclusion of natural resource governance within the social and economic indicators would render the Index a more complete analytical tool. In a 2009 report, the UN Environment Program (UNEP) found that “since 1990, at least eighteen violent conflicts have been fueled by the exploitation of natural resources,” and that effective natural resource management is a necessary component of conflict prevention and peacebuilding operations.

The Elephant in the Room: Predicting the Arab Spring

Why did the Index fail to predict the Arab Spring sweeping the Middle East and North Africa? Many critics assert that the inconsistent ranking of the states, ranging from Yemen (ranked 13th) to Bahrain (ranked 129th), demonstrates that the Index is a poor indicator of state instability. Particularly, critics argue that many of the countries experiencing revolutions were ranked artificially low.

“Of course, the Failed States Index did not predict the Arab Spring, and nor is it intended to predict such upheavals,” said Messner at the launch event. “But by digging down deeper into the specific indicator analysis, it was possible to observe the growing tensions in those countries.” The Index has consistently highlighted specific troubling indicators for the region, such as severe demographic pressures, migration, group grievance, human rights, state legitimacy, and political elitism.

Blake Hounshell, a correspondent with Foreign Policy (long-time collaborators with the Fund for Peace on the Index), wrote that the Index was never meant to be a “crystal ball” – even the best statistical data cannot truly encapsulate the complex realities that lead to inherently unpredictable events, such as revolutions. “It’s thousands of individual decisions, not rows of statistics, that add up to political upheaval,” Hounshell continued.

Demographer Richard Cincotta’s work on Tunisia’s revolution illuminates how the Index’s linear indicators can mask a complex reality. Whereas the Failed States Index simply measures “demographic pressure” as a linear function of how youthful a population is, Cincotta pointed out at a Wilson Center event that it was actually Tunisia’s relative demographic maturity that paved the way for its revolution and gives it a good chance of achieving a liberal democracy. Other countries in the region are much younger than Tunisia (Yemen being the youngest). The Arab Spring demonstrates that static indicators alone often do not have the capacity to predict complex social and political revolutions.

Sources: Foreign Policy, The Fund for Peace, UNEP.

Image Credit: Failed States Index 2011, Foreign Policy. -

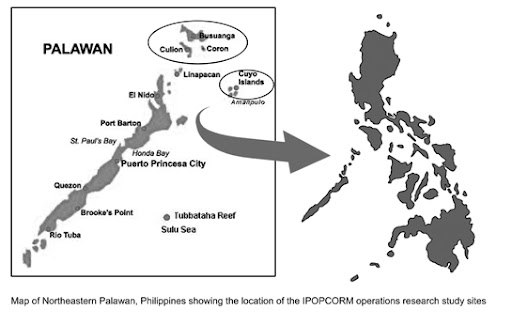

Leona D’Agnes on Evaluating PHE Service Delivery in the Philippines

›“By reducing population growth, we are going to have a better chance of sustaining the gains of an environmental conservation project,” said Leona D’Agnes in this interview with ECSP. D’Agnes, a technical advisor to PATH Foundation Philippines, served as lead author on a research article published late last year in Environmental Conservation titled, “Integrated Management of Coastal Resources and Human Health Yields Added Value: A Comparative Study in Palawan (Philippines).” The study provided concrete statistical evidence that integrated development programming incorporating population, health, and the environment (PHE) can be more effective in lowering population growth rates and preserving critical coastal ecosystems than single-sector development interventions.

“What set this research apart from earlier work on integrated programming was the rigorous evaluation design that was applied,” said D’Agnes. “What this design aimed to do is to evaluate the integrated approach itself. Most of the previous evaluations that have been done on integrated programming were impact evaluations — they set out to evaluate the impact of the project.” This most recent research project, on the other hand, sought to evaluate the effectiveness of cross-sectoral interventions based on “whether or not synergies were produced,” said D’Agnes.

Although it took her team six years to generate statistically significant findings in Palawan, D’Agnes reports that the synergies of PATH Foundation Philippines’ PHE intervention took the form of reduced income poverty, a decreased average number of children born to women of reproductive age, and the preservation of coastal resources, which helped bolster the region’s food security.

Going forward, D’Agnes said, an integrated approach to environmental conservation should also prove appealing because of its cost effectiveness. “This has huge implications for local governments in the Philippines, where they are struggling to meet the basic needs of their constituents in the face of very small internal revenue allotments that they get from the central government,” she said. “They can really pick up on this example to see that at the local level, if somehow they can do this integrated service delivery that was done in the Integrated Population and Coastal Resource Management (IPOPCORM) model, that they’ll be able to achieve the objectives of both their conservation and their health programs in a much more cost-effective way, and, in the process, generate some other [positive] outcomes that perhaps they didn’t anticipate.”

D’Agnes expects the study’s results will prompt a fresh look at cross-sectoral PHE programming. “I hope that this evidence from this study will help to change the thinking in the conservation community about integrated approaches to conservation and development,” she said.

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

Watch: Michael Renner on Creating Peacebuilding Opportunities From Disasters

›Michael Renner is a senior researcher at the Worldwatch Institute working on the intersection between environmental degradation, natural resource issues, and peace and conflict. Recently, Renner has focused on water use and its effects on the Himalayan region. In particular he’s working to find positive opportunities that can turn “what is a tremendous problem, into perhaps an opportunity for collaboration among different communities, among different regions, and perhaps…ultimately across the borders of the region,” he said during this interview with ECSP.

-

Preparing for the Impact of a Changing Climate on U.S. Humanitarian and Disaster Response

›Climate-related disasters could significantly impact military and civilian humanitarian response systems, so “an ounce of prevention now is worth a pound of cure in the future,” said CNA analyst E.D. McGrady at the Wilson Center launch of An Ounce of Preparation: Preparing for the Impact of a Changing Climate on U.S. Humanitarian and Disaster Response. The report, jointly published by CNA and Oxfam America, examines how climate change could affect the risk of natural disasters and U.S. government’s response to humanitarian emergencies. [Video Below]

Connecting the Dots Between Climate Change, Disaster Relief, and Security

The frequency of – and costs associated with – natural disasters are rising in part due to climate change, said McGrady, particularly for complex emergencies with underlying social, economic, or political problems, an overwhelming percentage of which occur in the developing world. In addition to the prospect of more intense storms and changing weather patterns, “economic and social stresses from agricultural disruption and [human] migration” will place an additional burden on already marginalized communities, he said.

Paul O’Brien, vice president for policy and campaigns at Oxfam America said the humanitarian assistance community needs to galvanize the American public and help them “connect the dots” between climate change, disaster relief, and security.

As a “threat multiplier,” climate change will likely exacerbate existing threats to natural and human systems, such as water scarcity, food insecurity, and global health deterioration, said Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, USN (ret.), president of CNA’s Institute for Public Research. Major General Richard Engel, USAF (ret.), of the National Intelligence Council identified shifting disease patterns and infrastructural damage as other potential security threats that could be exacerbated by climate change.

“We must fight disease, fight hunger, and help people overcome the environments which they face,” said Gunn. “Desperation and hopelessness are…the breeding ground for fanaticism.”

U.S. Response: Civilian and Military Efforts

The United States plays a very significant role in global humanitarian assistance, “typically providing 40 to 50 percent of resources in a given year,” said Marc Cohen, senior researcher on humanitarian policy and climate change at Oxfam America.

The civilian sector provides the majority of U.S. humanitarian assistance, said Cohen, including the USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. These organizations provide leadership, funding, and food aid to developing countries in times of crisis, but also beforehand: “The internal rationale [of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance] is to reduce risk and increase the resilience of people to reduce the need for humanitarian assistance in the future,” said Edward Carr, climate change coordinator at USAID’s Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance.

The U.S. military complements and strengthens civilian humanitarian assistance efforts by accessing areas that civilian teams cannot reach. The military can utilize its heavy lift capability, in-theater logistics, and command and control functions when transportation and communications infrastructures are impaired, said McGrady, and if the situation calls for it, they can also provide security. In addition, the military could share lessons learned from its considerable experience planning for complex, unanticipated contingencies with civilian agencies preparing for natural disasters.

“Forgotten Emergencies”

Already under enormous stress, humanitarian assistance and disaster response systems have persistent weaknesses, such as shortfalls in the amount and structure of funding, poor coordination, and lack of political gravitas, said Cohen.

Food-related aid is over-emphasized, said Cohen: “If we break down the shortfalls, we see that appeals for food aid get a better response than the type of response that would build assets and resilience…such as agricultural bolstering and public health measures.” Food aid often does not draw on local resources in developing countries, he said, which does little to improve long-term resilience.

“Assistance is not always based on need…but on short-term political considerations,” said Cohen, asserting that too much aid is supplied to areas such as Afghanistan and Iraq, while “forgotten emergencies,” such as the Niger food crisis, receive far too little. Furthermore, aid distribution needs to be carried out more carefully at the local scale as well: During complex emergencies in fragile states, any perception of unequal assistance has the potential to create “blowback” if the United States is identified with only one side of a conflict.

Engel added that many of the problems associated with humanitarian assistance will be further compounded by increasing urbanization, which concentrates people in areas that do not have adequate or resilient infrastructure for agriculture, water, or energy.

Preparing for Unknown Unknowns

A “whole of government approach” that utilizes the strengths of both the military and civilian humanitarian sectors is necessary to ensure that the United States is prepared for the future effects of climate change on complex emergencies in developing countries, said Engel.

In order to “cut long-term costs and avoid some of the worst outcomes,” the report recommends that the United States:

Cohen singled out “structural budget issues” that pit appropriations for protracted emergencies in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Darfur against unanticipated emergencies, like the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Disaster-risk reduction investments are not a “budgetary trick” to repackage disaster appropriations but a practical way to make more efficient use of current resources, he said: “Studies show that the return on disaster-risk reduction is about seven to one – a pretty good cost-benefit ratio.”- Increase the efficiency of aid delivery by changing the budgetary process;

- Reduce the demand by increasing the resilience of marginal (or close-to-marginal) societies now;

- Be given the legal authority to purchase food aid from local producers in developing countries to bolster delivery efficiency, support economic development, and build agricultural resilience;

- Establish OFDA as the single lead federal agency for disaster preparedness and response, in practice as well as theory;

- Hold an OFDA-led biannual humanitarian planning exercise that is focused in addressing key drivers of climate-related emergencies; and,

- Develop a policy framework on military involvement in humanitarian response.

Edward Carr said that OFDA is already integrating disaster-risk reduction into its other strengths, such as early warning systems, conflict management and mitigation, democracy and governance, and food aid. However, to build truly effective resilience, these efforts must be tied to larger issues, such as economic development and general climate adaptation, he said.

“What worries me most are not actually the things I do know, but the things we cannot predict right now,” said Carr. “These are the biggest challenges we face.”

“Pakistan Floods: thousands of houses destroyed, roads are submerged,” courtesy of flickr user Oxfam International. -

Watch ‘Dialogue’ TV on Severe Weather and Climate Change: Is There a Connection?

›This week on Dialogue, host John Milewski is joined by Heidi Cullen and Edward Maibach for a discussion on whether recent severe weather outbreaks in the United States and around the world are directly tied to the latest data on climate change. [Video Below] Dialogue is an award-winning co-production of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and MHz Networks that explores the world of ideas through conversations with renowned public figures, scholars, journalists, and authors. The show is also available throughout the United States on MHz Networks, via broadcast and cable affiliates, as well as via DirecTV and WorldTV (G19) satellite.

Dialogue is an award-winning co-production of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and MHz Networks that explores the world of ideas through conversations with renowned public figures, scholars, journalists, and authors. The show is also available throughout the United States on MHz Networks, via broadcast and cable affiliates, as well as via DirecTV and WorldTV (G19) satellite.

Heidi Cullen is a research scientist and correspondent for Climate Central where she also served as director of communications. Previously, she served as the Weather Channel’s first on air climate expert and is also a member of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Science Advisory Board. Edward Maibach joined the George Mason University faculty in 2007 to create the Center for Climate Change Communication. He is also a principal investigator of several climate change education grants funded by the National Science Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Find out where to watch Dialogue where you live via MHz Networks. You can send questions or comments on the program to dialogue@wilsoncenter.org.

Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

Double Choke Point: Demand for Energy Tests Water Supply and Economic Stability in China and the U.S.

›

The original version of this article, by Keith Schneider, appeared on Circle of Blue.

The coal mines of Inner Mongolia, China, and the oil and gas fields of the northern Great Plains in the United States are separated by 11,200 kilometers (7,000 miles) of ocean and 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) of land.

But, in form and function, the two fossil fuel development zones – the newest and largest in both nations – are illustrations of the escalating clash between energy demand and freshwater supplies that confront the stability of the world’s two biggest economies. How each nation responds will profoundly influence energy prices, food production, and economic security not only in their domestic markets, but also across the globe.

Both energy zones require enormous quantities of water – to mine, process, and use coal; to drill, fracture, and release oil and natural gas from deep layers of shale. Both zones also occur in some of the driest regions in China and the United States. And both zones reflect national priorities on fossil fuel production that are causing prodigious damage to the environment and putting enormous upward pressure on energy prices and inflation in China and the United States, say economists and scholars.

“To what degree is China taking into account the rising cost of energy as a factor in rising overall prices in their economy?” David Fridley said in an interview with Circle of Blue. Fridley is a staff scientist in the China Energy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “What level of aggregate energy cost increases can China sustain before they tip over?”

“That’s where China’s next decade is heading – accommodating rising energy costs,” he added. “We’re already there in the United States. In 13 months, we’ll be fully in recession in this country; 9 percent of our GDP is energy costs. That’s higher than it’s been. When energy costs reach eight to nine percent of GDP, as they have in 2011, the economy is pushed into recession within a year.”

Continue reading on Circle of Blue.

Photo Credit: Used with permission, courtesy of J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue. In Ningxia Province, one of China’s largest coal producers, supplies of water to farmers have been cut 30 percent since 2008.

The coal mines of Inner Mongolia, China, and the oil and gas fields of the northern Great Plains in the United States are separated by 11,200 kilometers (7,000 miles) of ocean and 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) of land.

But, in form and function, the two fossil fuel development zones – the newest and largest in both nations – are illustrations of the escalating clash between energy demand and freshwater supplies that confront the stability of the world’s two biggest economies. How each nation responds will profoundly influence energy prices, food production, and economic security not only in their domestic markets, but also across the globe.

Both energy zones require enormous quantities of water – to mine, process, and use coal; to drill, fracture, and release oil and natural gas from deep layers of shale. Both zones also occur in some of the driest regions in China and the United States. And both zones reflect national priorities on fossil fuel production that are causing prodigious damage to the environment and putting enormous upward pressure on energy prices and inflation in China and the United States, say economists and scholars.

“To what degree is China taking into account the rising cost of energy as a factor in rising overall prices in their economy?” David Fridley said in an interview with Circle of Blue. Fridley is a staff scientist in the China Energy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “What level of aggregate energy cost increases can China sustain before they tip over?”

“That’s where China’s next decade is heading – accommodating rising energy costs,” he added. “We’re already there in the United States. In 13 months, we’ll be fully in recession in this country; 9 percent of our GDP is energy costs. That’s higher than it’s been. When energy costs reach eight to nine percent of GDP, as they have in 2011, the economy is pushed into recession within a year.”

Continue reading on Circle of Blue.

Photo Credit: Used with permission, courtesy of J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue. In Ningxia Province, one of China’s largest coal producers, supplies of water to farmers have been cut 30 percent since 2008.

Top 10 Posts for June 2011

›

Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen joined his former staffers (see “In Search of a New Security Narrative“) on the New Security Beat top 10 list last month after speaking at the Wilson Center in the inaugural Lee Hamilton lecture. Richard Cincotta’s look at Tunisia’s demographics also remained popular, joined by several posts on climate, security, and development, including ECSP’s “Yemen Beyond the Headlines” event.

1. In Search of a New Security Narrative: The National Conversation at the Wilson Center

2. Tunisia’s Shot at Democracy: What Demographics and Recent History Tell Us

3. Connections Between Climate and Stability: Lessons From Asia and Africa

4. Admiral Mullen: “Security Means More Than Defense,” Inaugural Lee Hamilton Lecture at the Wilson Center

5. Climate Adaptation, Development, and Peacebuilding in Fragile States: Finding the Triple-Bottom Line

6. One in Three People Will Live in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2100, Says UN

7. India’s Maoists: South Asia’s “Other” Insurgency

8. Eye on Environmental Security: Where Does It Hurt? Climate Vulnerability Index, Momentum Magazine

9. Helping Hands: An Integrated Approach to Development

10. Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Losing the Battle to Balance Water Supply and Population Growth

1. In Search of a New Security Narrative: The National Conversation at the Wilson Center

2. Tunisia’s Shot at Democracy: What Demographics and Recent History Tell Us

3. Connections Between Climate and Stability: Lessons From Asia and Africa

4. Admiral Mullen: “Security Means More Than Defense,” Inaugural Lee Hamilton Lecture at the Wilson Center

5. Climate Adaptation, Development, and Peacebuilding in Fragile States: Finding the Triple-Bottom Line

6. One in Three People Will Live in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2100, Says UN

7. India’s Maoists: South Asia’s “Other” Insurgency

8. Eye on Environmental Security: Where Does It Hurt? Climate Vulnerability Index, Momentum Magazine

9. Helping Hands: An Integrated Approach to Development

10. Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Losing the Battle to Balance Water Supply and Population Growth