Showing posts from category *Blog Columns.

-

Gwen Hopkins, Aspen Institute Global Health and Development

Aspen Ideas Festival Takes on “The Population Challenge”

›The original version of this article, by Gwen Hopkins, appeared on the Aspen Ideas Festival blog.

The pictures flash quickly: lush sea vegetation replaced by empty grey-blue seabed as carbon bubbles out of undersea vents. Reservoirs depleted too quickly, never to refill. Forests and mountains leveled for coal, deep sea oil rigs ablaze, the arctic ice cap visibly retreating. Dennis Dimick is answering the question posed to him with a litany of evidence collected by National Geographic: Does population matter?

Yes, he says – a lot.

Kicking off the Our Planet: The World at Seven Billion track, on a panel called “The Population Challenge,” Washington Post staff writer Joel Achenbach moderated a conversation between Dimick and Helene Gayle, president and CEO of CARE USA, following Dimick’s presentation about how the earth’s human population has made its presence known.

Dimick explains that this new geologic era has been dubbed Anthropocene, the age of man, as we “transform the planet to perpetuate our lifestyle.” That’s a lifestyle powered first and foremost by what he calls “the new sun” – coal, oil, and gas, or in Dimick’s words, “ancient plant goo.” These transformations are deep and widespread – and according to Dimick, growing worrisome in their magnitude. While there is searing inequity – “few have a lot, and a lot have few” – those that lead the consumption have, for example, caught 90 percent of the big fish in the sea already, and burn in one year a quantity of fuel that took a million years to coalesce underground. “If everyone in the world lived like Americans do, we’d need four planets.”

Continue reading on the Aspen Ideas Festival blog.

Photo Credit: Aspen Institute. -

What Are the Most Important Factors in the Failed States Index?

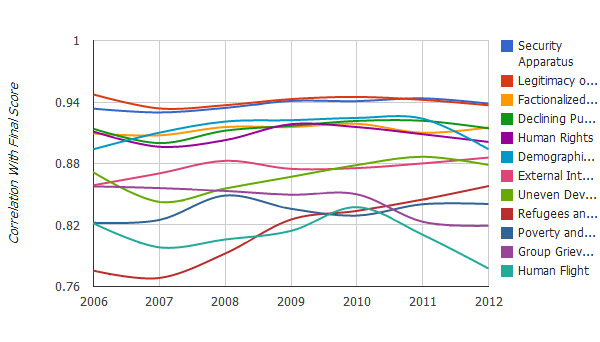

›Last week, the Fund for Peace issued its eighth annual Failed States Index (FSI). The index gives 177 countries a score between 1.0 and 10.0 for 12 indicators, ranging from the legitimacy of the state and the security apparatus to demographic pressure and uneven development (high being bad, low being good – see full descriptions of the indicators here). But which of these indicators has the biggest impact? We did a quick analysis of the Failed States Indexes published from 2006 to 2012 to show which of the indicators correlate most with a high score. (We skipped 2005 since the roster of analyzed countries was significantly smaller.)

-

IPPF and Partners Connect Reproductive Rights With the Environment and Development

›A new framework for sexual and reproductive health is needed, argued panelists in a recent event at the Wilson Center, and the Rio+20 conference on sustainable development would have been the place to start. An international consensus around women’s human rights was developed at the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994, but Carmen Barroso, director of the International Planned Parenthood Federation’s Western Hemisphere Region, said there has been slow implementation, little funding, and furthermore the world has changed significantly since then.

Barroso was joined by Latanya Mapp Frett, vice president of Planned Parenthood Global, as well as two representatives of Planned Parenthood partner organizations, Marco Cerezo of FUNDAECO and Ben Haggai of Carolina for Kibera.

New challenges to the reproduce rights landscape include the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS and decreased funding for international programs. But new opportunities include rapid dissemination provided by the internet and globalization and a subsequent mobilization of youth. “Young people are the largest cohort in history,” Barroso said in an interview with ECSP, both in absolute numbers and in percent of the population. “We have a historical opportunity [to incorporate] them in these decision-making processes.” Additionally, gender and health issues are incresaingly seen by many as linked with the environment and development.

Intersection of Health and the Environment

Marco Cerezo’s FUNDAECO (Foundation for Ecodevelopment and Conservation) is an example of Planned Parenthood’s partnership with other organizations. Based, in rural Guatemala, they shifted from primarily focusing on conservation and sustainable development to incorporating women’s health after finding a vicious cycle of poverty, high fertility, and environmental degradation in the places they worked.

Women’s health was so dire it was holding development back, Cerezo said. “Sustainable community development will not be possible without the education, empowerment, and support to rural women,” they write in their mission statement.

FUNDAECO now acts as a model for the intersection between reproductive health and the environment. Cerezo reported that once women are healthy and empowered through clinics established by FUNDAECO, they become more active in all aspects of the community, including ecological preservation.

Building Healthy Communities

Ben Haggai, who works in Nairobi’s biggest slum, Kibera, further reiterated the need for integrated programs. Carolina for Kibera has a number of programs to improve the quality of life for residents, he said, and has a particular focus on youth with sports associations and education programs.

Youth are the best reproductive health educators, Haggai said, as they are able to talk frankly with their peers. The NGO trains peer youth educators to reach out to community members about reproductive health and other issues like substance abuse. Since the young people work as volunteers, Haggai said, they are motivated only by a desire to improve their communities.

A Natural Intersection

Latanya Mapp Frett agreed that sexual and reproductive health aligns quite naturally with issues of sustainability. “We try to work in the countries overseas in Latin America and Africa where we focus particularly on non-traditional health sectors,” she said in an interview with ECSP following the panel. “One of those sectors is the environment.”

While emphasizing that contraceptive use is a cost-effective way to ensure sustainable development, Mapp Frett cautioned against framing sexual and reproductive health only in the context of reducing fertility. While this may have been common in the past, she noted, it’s important to ensure that women have the right to make childbearing choices for themselves.

Mapp Frett also urged policymakers in the United States to look to developing countries for intersections between development, the environment, and reproductive health. She said that Planned Parenthood’s partner organizations, including FUNDAECO and Carolina for Kibera, have found these connections and successfully partnered with already existing networks like churches to more effectively reach the community.

Translating Into Effective Action

Each member of the panel spoke about the challenge of articulating the need for sexual and reproductive health programs to people outside the field. Barroso mentioned research conducted by Brian O’Neill which found that meeting the current unmet need for contraception would slow population growth enough to reduce emissions by 17 percent.

Cerezo emphasized the importance of consensus among the staff of a given organization, saying it is difficult to make a case to agronomists and farmers if a culture clash exists within the institution. Haggai agreed, adding that focusing on reproductive issues is an important measure of prevention which helps protect both the environment and the health of women in a community.

For Mapp Frett, women’s reproductive and sexual health is indivisible from other aspects of development. “As you talk about sustainable development, you talk about ensuring that women are empowered to make sure that our earth is sustainable,” she said.

Assessing Rio+20

The panel took place before the UN Conference on Sustainable Development got underway in Rio. Participants had high hopes for a renewed focus on gender and reproductive rights at the conference. Unfortunately, language on reproductive rights was first weakened and then omitted entirely from the final outcome document (see the account written by ECSP’s Sandeep Bathala at Rio for more on the conference).

While pressure from the Vatican and the G-77 kept reproductive health out of the outcome document, it was not entirely forgotten at the conference. A number of side events highlighted the importance of reproductive rights, especially in the context of the environment and development.

Hillary Clinton also re-affirmed U.S. commitment to access to contraception and reproductive health care. “Women must be empowered to make decisions about whether and when to have children,” she said at the conference on Friday. “And the United States will continue to work to ensure that those rights are respected in international agreements.”

Clinton shared the urgency expressed by the panelists at the Wilson Center. “There is just too much at stake, too much still to be done,” she said. “We simply cannot afford to fail.”

Event Resources:Sources: FUNDAECO, UN Conference on Sustainable Development, U.S. Department of State.

Photo Credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center. -

The Economist

Afghanistan’s Demography: A Bit Less Exceptional

›The original version of this article appeared in The Economist, and is based on ECSP Report 14, Issue 1.

This is a story from Afghanistan which is not about fighting, bombs, or the Taliban. It even contains a modicum of good news. It is about demography.

Afghanistan has long been seen as a demographic outlier. In 2005-10, according to the United Nations Population Division, its fertility rate was 6.6 – the second-highest in the world after Niger (the fertility rate is the number of children a woman can expect to have during her lifetime). The contrast with the rest of South Asia is extreme: fertility ranged from four (in Pakistan) to below three (in Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka). Afghanistan’s sky-high fertility seems consistent with a view of the country as trapped in an exceptional and dysfunctional mode of development, marked by war, religious extremism, tribal honor codes, and the subjugation of women.

But this fertility rate was always a bit of a guess. The last census was taken in 1979, the year of the Soviet invasion. A whole generation has grown up since then, amid pervasive violence and uncertainty. It has been extremely hard to know how fertility has been changing.

Hence the significance of the Afghanistan Mortality Survey. Based on interviews with 48,000 women and girls aged 12 to 49, it is the nearest thing the country has had to a national census for 30 years (there were smaller surveys in 2003 and 2007-08, but their coverage was not national).

Continue reading on The Economist.

Read more about the Afghanistan Mortality Survey here on the blog with Elizabeth Leahy Madsen’s original posts here and here.

Photo Credit: “Celebrating International Women’s Day in Afghanistan,” courtesy of the U.K. Department for International Development. -

Alexandra Cousteau on the Global Water Crisis and Choosing Between the Environment and the Economy

›Above is a short discussion filmed after a full dialogue TV episode last week; for the full interview, please visit the Wilson Center.

“We have serious issues that we need to address, yet we’re largely unaware of them because water seems so abundant,” said Alexandra Cousteau in an interview at the Wilson Center. “That myth of abundance is finally reaching an age of limits.”

Cousteau spoke with John Milewski of the Wilson Center’s dialogue TV program, after an event on the recent global water security assessment by the U.S. intelligence community. She discussed the work of her organization, Blue Legacy, which seeks to raise awareness of the ‘global water crisis’ – from degrading quality to growing scarcity and the proliferation of water refugees.

Global Water Crisis

“Traditionally our understanding of the global water crisis has been very narrow,” said Cousteau. “We have talked about it mostly in terms of the very real water and sanitation crisis that is happening in the developing world.” Without minimizing the severity of the situation in developing countries or oversimplifying the tangled nature of their problems, she characterized these water and sanitation struggles as fundamentally “solvable.”

Cousteau argued that there are also substantial water problems in the United States. Pollution due to runoff and over-utilization of major riverways are threats that are much different from those in the past.

“In Nixon’s time, when he signed the Clean Water Act, it was because rivers like the Potomac were in such bad shape, and they could see it from their office windows,” she said. “But the threats to our water are different today…before, it was industrial effluent, and what we were putting in the water that we could see. The Hudson River would change color daily based on the paper mills and what color paper they were printing that day.”

Today, chemicals may impact water quality without changing the appearance of water: “You don’t see it, the water can be perfectly transparent.”

Blue Legacy Expeditions

Cousteau has taken two expeditions with Blue Legacy to highlight water issues around the world. The first in 2009 was global; Cousteau and her team traveled from India to Botswana and beyond. Throughout the voyage, she worked to make her travels accessible to the general public and was surprised at her success.

“It was an experiment, but it worked. And when we came back to the United States, we got a lot of feedback, and one of the things people said was, ‘Gosh, that was an incredible adventure, thanks for taking us along for the ride! Clearly, there is a global water crisis, now I understand that. I’m just so relieved it’s not happening in America.’ And I thought, ‘Oh my Lord, I guess we have an expedition to do in America!’”

Her 2010 North America expedition focused on issues ranging from the over-exploited Colorado River to the polluted Mississippi, and sought to make water problems personal “at a time when our demand on water is at a tipping point.”

The Environment and the Economy

Cousteau’s interview was particularly timely in light of global economic troubles which have led some to say the environment should take a backseat. Cousteau said this doesn’t have to be the case. She emphasized the interconnected nature of the environment and the economy, saying that policymakers don’t have to choose to focus on one or the other.

“We feel like we have to make a choice between the economy and the environment, and that’s a false dilemma. A healthier environment is a more prosperous economy. And when we fail to realize that we don’t have to sacrifice one to have the other, then I think we wind up sacrificing a lot of the quality of life and the opportunity that we take for granted.”

Video Credit: Dialogue/Wilson Center and Alexandra Cousteau. -

Population Projections: Breaking Down the Assumptions

›“The seventh billion [person] was added in 12 years, and that could be the story for the eighth billion – and that gets people who think that growth has stopped,” said Carl Haub, senior demographer at the Population Reference Bureau. Haub was joined by Hania Zlotnik, former director of the UN Population Division, and Rachel Nugent of the University of Washington’s Department of Global Health on June 5 to speak about the assumptions behind the UN population projections. While each of the panelists noted the utility of projections, they also cautioned against seeing them as inevitable. [Video Below]

Meeting the Projections

As a former top official in the UN’s Population Division, Zlotnik spoke about how much is riding on the projections. “The experts tell me that to feed nine billion people, living better than the standards of living that we have today, one needs to increase agricultural production or all the production of food by about 70 percent and that is a challenge, but it might be feasible. But if the numbers go higher…I think it’s impossible,” she said.

The medium variant projection by the UN that gets the world to that nine billion figure is not a given – it builds in expected action on and improvement of many demographic indicators. Zlotnik pointed to the global unmet need for family planning, for example, which “is especially high in the high fertility countries,” and suggested that the current rate of increase in contraceptive use is insufficient.

She calculated the number of years it would take many of these countries to meet their unmet need at their current rate of uptake and found “the number of years for a lot of these poorer countries that have high fertility would be very long – 40 years, some of them, 80 years, 100 years – because the increased contraceptive prevalence has been so small.” At that rate, population growth in these countries will far surpass the UN medium variant.

The perception that population growth is no longer an issue contributes to the problem, Zlotnik said. People see that only 18 percent of the world population lives in countries with high population growth and assume “there’s no longer a population problem.” But she emphasized the power of exponential growth, arguing that even a small proportion growing at a rapid rate can have a large impact.

Questioning Assumptions

Haub pointed out several instances where assumptions in the methodology behind the projections create uncertainty.

For example, there is a lack of data in many low-income countries. “A date, let’s say 2000, 2005 – it’s the past, but it may be a projection. It may be based on a census in 1990,” he said. If it’s wrong, that error may not be corrected until another census, but it will still be relied on for country-level projections.

He also noted that certain assumptions about desired family size sometimes do not bear out on the ground. One of the key methods to slowing population growth is to provide women and couples with the means to choose how many children they wish to bear. But in many fast-growing countries, women wish to have large numbers of children. In Niger, for example, women say their ideal family size is over nine children. Such women are less likely to use contraception, no matter how accessible it is, as they value larger families.

“It has been – I guess conventional is a good word – to assume that birth rates are going to come down the way they did in the rich countries,” Haub noted. But there has been a “stall” for many developing countries, which he suggests is caused by fast initial uptake from urban women followed by much slower uptake by rural women. These dynamics, however, are relatively new and therefore are not always well incorporated into current projections.

The Economic Impact of Population Changes

While Haub and Zlotnik looked at the assumptions made before the projections are made and the importance and means to reach these projections, Nugent focused on the economic implications of lower fertility and the demographic transition.

She suggested that increased control over fertility can positively impact a country’s economy. Women are given the opportunity to “invest their time in acquiring skills and investing time in the labor market and that affects their earnings…[and] their ability to control resources and make decisions within the household” as they spend less time caring for children, she said.

The labor market changes as well, as fewer children are born into a given generation. This can reduce “demand on economic resources [and] demand on environmental resources,” and the increased investment in human capital allowed by smaller family sizes can lead to a healthier population.

Nugent concluded by pointing out key areas of intervention most likely to decrease both fertility and mortality and allow countries to reap the positive economic benefits of fertility decline. She suggested a focus on “complementary investments in education and health,” especially with regard to “poor and marginalized populations,” which can in fact impact the country as a whole. Finally, she recommended focusing on proven “evidence-based programs [and] service-delivery programs.”

Educating Policymakers

Each of the panelists cautioned against relying on population projections without taking action to make them come true.

“Maybe the best thing to do if you’re giving a presentation is to show the UN’s constant fertility variant first and scare people half to death and then say, ‘but if 117,000 things go right, [the medium variant projection] is what will happen,” said Haub, addressing the common tendency to view the UN projections as destiny.

Similarly, Nugent warned against viewing the demographic transition as inevitable. “There’s a certain sense…that [the demographic dividend] is kind of an automatic thing that happens, and that really has to be addressed,” she said, adding that “it’d be quite interesting to show some scenarios of what would need to be done…in order to get some benefits from that dividend.” (See also Elizabeth Leahy Madsen’s recent article on achieving the dividend.)

Zlotnik reiterated that the UN does not in fact know what the future will bring. “It’s not that we know what the world is going to do, but we hope that [the projections] will get the message out – if this doesn’t happen, you’re in trouble.”

Event ResourcesPhoto Credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center. -

Climate-Conflict Thresholds and Water as a Casualty of Conflict

›While numerous studies have examined the perils faced by businesses operating in conflict-affected or high-risk locations, Water as a Casualty of Conflict: Threats to Business and Society in High-Risk Areas, written by Kristina Donnelly, Mai-Lan Ha, Heather Cooley, and Jason Morrison, is the first such report to focus specifically on water. The report – a collaborative effort between the UN Global Compact and the Pacific Institute – aims to provide a framework for understanding the conflict-water-business nexus by first tracing the ways in which conflict and high-risk areas can adversely impact local and regional water systems and then illustrating the challenges such impacts can pose to businesses in conflict-affected or high-risk areas. Water as a Casualty of Conflict was published online this week and was introduced at a Rio+20 Corporate Sustainability Forum panel session.

In an article titled “Climate Change and Violent Conflict,” appearing in the May 18th edition of Science, authors Jürgen Scheffran, Michael Brzoska, Jasmin Kominek, Michael Link, and Janpeter Schilling attempt to sort out some of the controversy surrounding the intersection of climate change and violent conflict. They urge greater interdisciplinary research to identify and provide solutions for possible “tipping points” where the impacts of climate change may prove too great for human adaptive capacity. Such research has been scarce due to difficulties in collecting sufficient data. Moreover, the authors note that many of the extant studies on climate change and conflict are flawed because of how they define violent conflict. The commonly-used Uppsala Conflict Data Program and Peace Research Institute Oslo (UCDP-PRIO) Armed Conflict dataset, for instance, excludes by definition many riots, protests, incidences of livestock theft, and other violent or potentially violent behaviors. This is problematic because, as the authors point out, “in recent decades, climate variability may have been more associated with low-level violence and internal civil war – which fall below the UCDP-PRIO definition cutoff – than with armed conflict or war between countries.” -

Royal Society Launches ‘People and the Planet’ Study

›“This is a time of rapid and multifaceted change in both population and the planet,” said Parfait Eloundou-Enyegue, a member of the U.K. Royal Society’s People and the Planet working group and contributing author to the report of the same name launched at the Wilson Center on June 4. “The question that the report is trying to address is whether we can actually envision a world in which we can sustainably and equitably meet the consumption needs of seven billion people, and the more to come.” [Video Below]The Royal Society is a self-governing fellowship of scientists that fosters research to address pressing social issues and better inform policy on a global scale. Eloundou-Enyegue, also an associate professor of development sociology at Cornell University, was joined by fellow working group member and African Institute for Development Policy Director and Founder Eliya Msiyaphazi Zulu to discuss their assessment of growing population and consumption pressures on global wellbeing.

Current Trends Are Unsustainable

“The current trends of global population growth and material consumption and the concomitant changes in the environment are unsustainable,” said Zulu.

On the population side, “you have changes that are affecting not just the size, the growth of the population, but also changes in family structure, in the population distribution, [and] population movement,” said Eloundou-Enyegue.

On the consumption side, “beyond the increase in consumption itself, there’s also a dramatic rise in aspiration,” he continued. “People are in greater contact and this tends to encourage…an increasing aspiration to mimic or to emulate the consumption standard of the more industrialized countries.”

Limits to Equitable Growth

When measuring consumption, which itself tends to be a misplaced barometer of wellbeing, according to Eloundou-Enyegue, there is a “disproportionate focus on GDP.”

Using GDP growth as a measure of consumption and wellbeing both “misses a lot of the economic production that’s not mediated through the market,” and “counts as positive things that are damaging to the planet,” he said.

The People and the Planet report marks a departure from the traditional consumption framework by asking “about the relevance of growth – is growth what we ought to be after?”

“The report tried to make a distinction between two types of consumption – the consumption of material resources and the consumption of goods and services – that are all relevant to wellbeing but have different implications for the environment,” Eloundou-Enyegue said. “So there is a need to think about how to shift or to favor consumption that is less damaging to the environment.”

Not an “Either-Or” Proposition

There is “a tendency to look at population and consumption when you’re addressing the impact of the environment in an either-or format, as if you had to choose either population as being the main culprit or consumption,” said Eloundou-Enyegue. “The reality is that they all have to be integrated and considered jointly.”

At the same time, there is “a tendency to shy away from population issues when you set development goals because they tend to be controversial,” he said. And yet, said Zulu, “there’s no question about it, the global population growth needs to be slowed down and ultimately stabilized for both people and the planet to flourish.”

The vast majority of future population growth is expected to come from Africa. Based on the United Nation’s medium variant projection, 70 percent of global population growth over the rest of the century will come from the continent.

That projection, however, belies a big assumption: “that the high fertility countries now will follow the same pattern in decline in fertility as the countries that have [already] achieved lower fertility had [in the past],” said Zulu, which “may actually not be the case.”

“You might actually find a situation where fertility might stabilize around three to four children in some of the…least developed countries,” he said, “and if that happens, it means that actually we stand a much, much bigger chance of getting to the high variant [of 15.8 billion by 2100] than we often tend to assume.”

In spite of that dire warning, however, Zulu said that “we should recognize that demography is not destiny, that through…appropriate socioeconomic and health policies and investment, we can actually slow down population growth.”

The report concludes that voluntary and non-coercive “reproductive health and family planning programs are urgently required,” said Zulu. “There is also a need for strong political leadership and financial commitment to make sure that these programs and services reach out to all women around the world who need them.”

Have We Missed the Boat Again?

Part of the urgency from the working group is because, so far, commitments to reproductive health appear to be falling short. It is the international community’s responsibility “to make sure that women have the contraceptives that they need in order to achieve their fertility aspirations,” said Zulu, but some of the most important agenda-setting events in global development over the past 20 years have sidelined population, reproductive health, and family planning.

The Millennium Development Goals, for instance, “tried to stay clear of population,” said Eloundou-Enyegue, even though “all the indicators that I see are either intrinsically demographic or have a strong demographic component.”

“If you think about stratification and the reproduction of inequality and poverty across generations and the role that differential fertility and reproduction plays, there’s no way you can sidestep population,” he continued. “If you’re talking about maternal mortality and child mortality…it doesn’t make sense to set population aside.”

Now, as the international community prepares for the upcoming Rio+20 summit, “there’s been a big struggle to get…consideration of population issues” on the agenda, said Zulu.

“Population is at the peripheral of all those discussions,” said Zulu. When in Nairobi for a preparatory conference earlier this year, Zulu said UNFPA Executive Director Babatunde Osotimehin “told me that he was quite alarmed that there was hardly any mention of population in all those discussions. And he asked me the question, ‘have we missed the boat again?’”

That concern reinforces the main argument of People and the Planet, said Zulu: there is an “urgent need to reduce material consumption of the richest, and increase consumption and healthcare for the poorest 1.3 billion people.”

“We’re talking about having the majority of people in the world being able to flourish, being able to lead decent lives.”

Event Resources:Photo Credit: “Market_Kampala, Uganda,” courtesy of the Hewlett Foundation.