-

Solving Vietnam’s Mangrove Mystery: Mekong Delta Living Lab

October 10, 2024 By Lindsey SchwidderIn spring 2024, I travelled in the Mekong Delta with Vietnamese researchers to investigate the country’s dwindling mangroves.

One day while hiking along the coastline of Bac Liu Province in southern Vietnam, we came across the remains of a once-flourishing mangrove forest now littered by countless concrete blocks. My colleagues noted that the decades-long trend of disappearing mangroves here seemed to be unstoppable.

This sobering experience brought to mind the words of one of my professors back in the Netherlands, who often spoke about the unique ability of mangrove ecosystems to thrive in harsh conditions—from salty and waterlogged soils to frequent floods from hurricanes. Mangroves are powerful symbols of resilience and adaptability and we can learn from them.

In face of climate change, however, a resilient and new “ecosystem” of humans must help these mangroves survive and thrive. Professional and citizen scientists will play a specific role in collecting data and designing scientifically sound solutions to advance mangrove protection efforts.

Coastal Climate Warriors

The disappearance of many mangrove forests in the Mekong Delta, and particularly in Vietnam, has triggered severe coastal erosion. Mangroves occupy less than 1% of the world’s surface, but as nature’s “climate warriors” they protect coastal ecosystems and ensure the well-being of local communities.

Young mangrove trees behind a concrete revetment in the Mekong Delta

Young mangrove trees behind a concrete revetment in the Mekong DeltaMangroves are an integral element in boosting Vietnam’s resilience in the face of sea-level rise emerging from climate change. They possess the potential to store up to four times more carbon than tropical forests. And the fact that well-managed mangrove forests are a bountifully biodiverse ecosystem harboring birds, fish turtles and crustaceans is equally important.

What drives the accelerating loss of mangrove forests along the Vietnamese coastline is not always clear. Many coastal protection projects have deployed concrete breakwaters and sea dikes to combat erosion. Ironically, such hard structures often thin mangrove forests. And many other efforts to protect them also are failing. The Vietnamese government invests heavily into planting new forests, but often without a sound knowledge of the science required to do so successfully.

Closing this knowledge gap has motivated Vietnamese academics to partner with my institution—the Netherland-based Delft University of Technology (TU Delft)—to launch a living lab in the Mekong Delta. This “no-walls” lab enables scientists to create hands-on citizen science experiences to increase understanding and awareness among policymakers and the public on how to better protect the mangrove ecosystems in Vietnam.

Failing concrete structures and declining mangrove forests in Bac Lieu province in the southern tip of Vietnam.

Knowledge Flowing Between Deltas

Like Vietnam, the Netherlands is a country highly susceptible to both sea-level rise and river flooding. After the disastrous 1953 floods, the Dutch government established a legal framework for flood protection, and realized a series of impressive delta works.

This so-called Dutch Delta approach had made the Netherlands one of the best-protected delta areas of the world, and an international repository for expertise in delta management, TU Delft is at the center of partnerships with universities around the globe to share the nation’s extensive water management knowhow.

As part of these efforts, TU Delft has created strong partnerships with two Vietnamese institutions in recent years: Thuy Loi University (1998) and Hanoi University of Natural Resources and Environment (2018). The exchange of students and academic staff and the joint development of facilities and programs for education and research are central to this cooperation, and also the driving force of the Mekong Learning Lab.

More than fifteen students from Vietnam have obtained their doctorate at TU Delft, exploring research on water and coastal management (mainly focused on the Mekong Delta). They have returned to Vietnam to help shape its national agenda and challenge policymakers to take action to help deltas and coastlines become more resilient to climate change. They are also nurturing a new generation of Vietnamese researchers universities, and are a homegrown resource to replace the use of foreign consultants.

Hands-on Lab Solutions

Coastline development and climate changes pressures pose dual threats to the mangrove population. So the Mekong Living Lab extends its work past technical research to spark social innovations to help solve this crisis.

Researchers in the lab are filling in the data gaps in research and monitoring various locations throughout the delta. Field measurements help them gain valuable insight into what’s happening. The joint Vietnamese and TU Delft team also explores tricky questions: Under what conditions do young trees thrive or struggle? How does sediment transport or pollution by plastic disrupt mangrove ecosystems? Why does one kind of sea wall function well in one area, but fail just 5-kilometers upstream?

Field measurements by Vietnamese researchers and students.

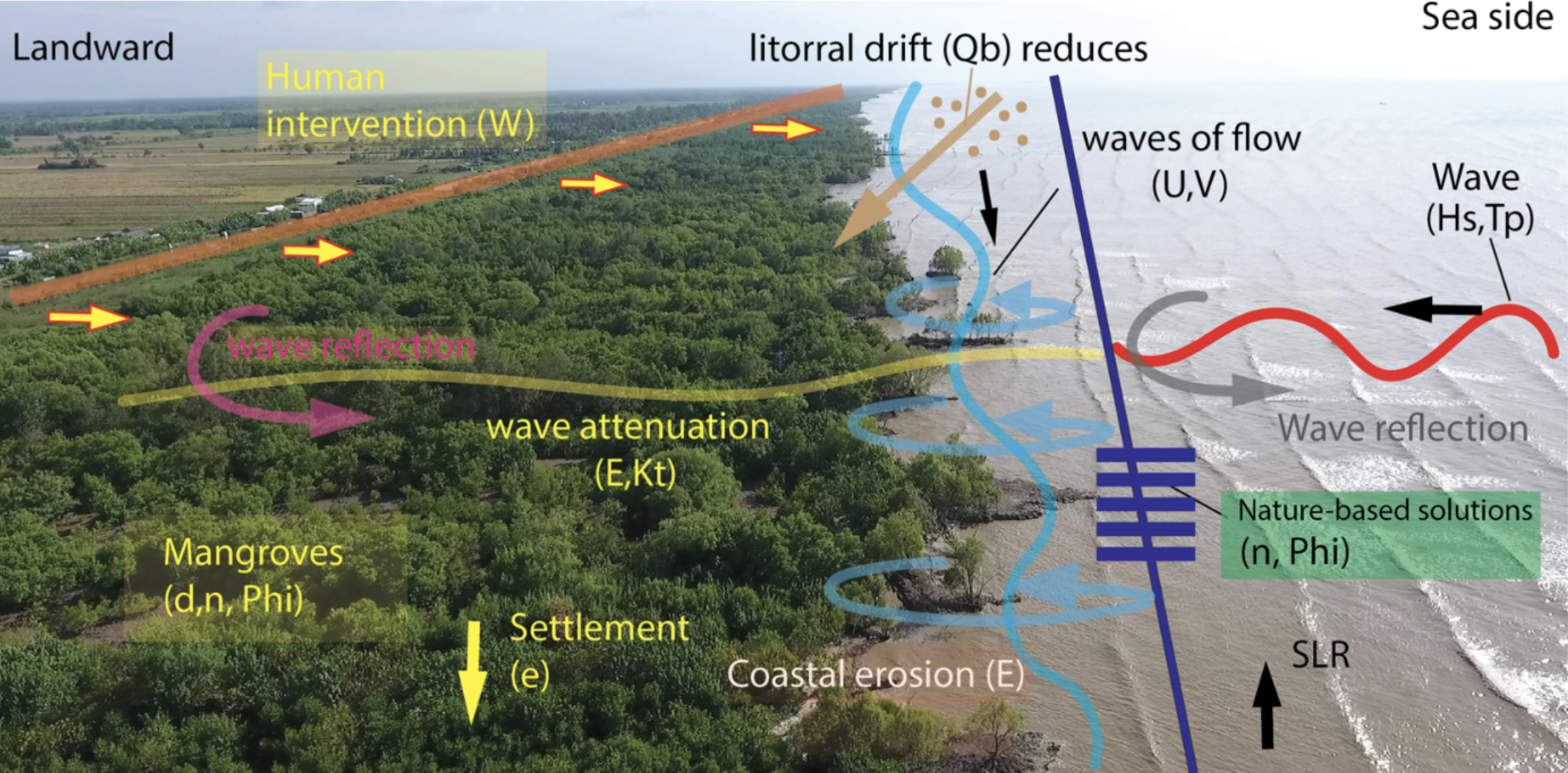

One important observation that has emerged is that each stretch of coastline is unique in terms of ecological processes. Moreover, each coastal mangrove system possesses numerous complex and interrelated processes. (See arrow-rich illustration below) These nuanced interactions pose a challenge for policymakers since there are no one-size-fits-all solutions on offer.

Several physical processes are involved in and around a fringe of coastal mangrove forest to determine its health or potential destruction. The challenge the Mekong Learning Lab faces is how to communicate this complexity to policymakers and communities.

Authorities and local residents use the lab as an information center and demonstration space to gain insight into appropriate nature-based planting and management solutions for their coastal areas. We bring local schools and communities to visit mangroves and understand the importance of protecting these ecosystems, and hold regular discussions and field visits for local authorities in Vietnam to foster collaboration and understanding.

At present, contradictory policies that encourage tree planting and expanding coastal aquaculture in the same mangrove systems exist in Vietnam. The latter efforts can undermine mangrove restoration efforts. So the Living Lab’s educational and networking efforts not only clarify science, but improve coordination among government agencies as they set and implement mangrove conservation policies.

Obtaining clear scientific data and developing management insights can help stakeholders understand that finding potential solutions can be very difficult. In the end, however, our goal is to ensure that our data sharing will translate into better policymaking and more sustained financing to protect these valuable ecosystems.

This blog is part of the Wilson Center-East-West Center Vulnerable Deltas project that is diving into climate, plastic waste and development threats to three SE Asian and two Chinese deltas. The project is supported by the Luce Foundation.

Lindsey Schwidder works on water and climate issues at the Innovation & Impact Centre of the Delft University of Technology’s Green Village—a campus-based living lab for sustainable innovation. She is the project manager of the Mekong Delta Living Lab project in Vietnam.

Acknowledgement: The Mekong Delta Living Lab is funded from the Partners for Water program of the Dutch government

Lead photo credit: Mangrove forest in Ca Mau province, Mekong delta, south of Vietnam, Photo courtesy of Vietnam Stock Images / Shutterstock.com

All other photo credits: Photos courtesy of TU Delft

Sources: Frontiers, International Association of Dredging Companies, Mongabay

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.