-

‘Interview:’ Educate Girls, Boys, To Meet the Population Challenge, Say Pakistan’s Leading Demographers

›June 25, 2010 // By Russell SticklorPakistan is at a major demographic crossroads. With a youth-heavy population of some 180 million and an annual population growth rate around 2 percent, the country’s population is projected to swell to roughly 335 million by mid-century. Such explosive growth raises major questions about Pakistan’s future, from looming food and water scarcity, to yawning inequalities in the nation’s educational and economic systems. Some warn that these problems threaten to drive a new generation of disaffected Pakistani youth toward political and religious radicalization.

Recently, I asked a number of leading Pakistani demographers visiting the Wilson Center how their country could best achieve more sustainable population growth rates and effectively harness the economic potential of Pakistani youth.

Educate Girls

Zeba Sathar, Pakistan country director for the Population Council in Islamabad, told me empowering girls through education represents one of the most important means of reducing the total fertility rate, which currently stands at four. “When children are educated—particularly when girls are educated—they take care of their fertility and their family size themselves,” Sathar said.

Yet securing educational opportunity for Pakistani girls has often been an uphill battle, largely due to entrenched social norms. Yasmeen Sabeeh Qazi, Karachi-based senior country adviser for the David and Lucile Packard Foundation’s Population Program in Pakistan, pointed out that a traditional preference for male children in Pakistani society has meant girls do not often receive the same level of family resources as males. This phenomenon has historically fed gender inequality, she said.

“Since boys are preferred, girls are not given the same kind of attention and nutrition, especially in the poorer and less-educated families,” Qazi told me. “But as the education level goes up, you see that this divide starts narrowing.” For Qazi, one of the keys to heightening educational access for girls is to increase both the quantity and quality of schools in rural districts, where two-thirds of Pakistanis live.

Decentralize Family Planning Services

Others I spoke with emphasized improving access to reproductive health and family planning services in rural and urban areas. The federal government’s relatively recent move to delegate operational authority for family planning services to the provincial or district level has encouraged many, such as Dr. Tufail Muhammad with the Pakistan Pediatric Association’s Child Rights & Abuse Committee in Peshawar.

Muhammad said the ongoing decentralization—which he described as “a major paradigm shift”—is meant to increase ownership of population planning policies at the local level, and therefore lead to more effective implementation because “the responsibility will be directly with the provincial government.” Once capacity is established at the local level to design and implement those policies, Muhammad added, “supervisors, administrators, and policymakers will be very close to [family planning] services.”

Manage the “Youth Bulge”

Yet despite the fact that both the public and private sectors are taking steps to address Pakistan’s growth issues, the population crunch will intensify before it potentially eases. Even assuming that greater educational opportunity for girls and increased local control over family planning services help drop Pakistan’s total fertility rate, the sheer size of the current youth bulge—two-thirds of the country’s population is under age 30—means population issues will inform every aspect of Pakistani society for decades to come.

In discussing the current state of Pakistan’s education system, some speakers also asserted that the influence of madrassas, or religious schools, over the student-aged population has often been overstated. Shahid Javed Burki, Pakistan’s former finance member and recent senior scholar at the Wilson Center, said during the panel discussion that inaccurate enrollment estimates created “the impression that the system is now dominated” by those institutions. He noted that more recent figures place madrassa enrollment at just five percent of the total student population.

With a majority of Pakistani students enrolled in regular public schools, he insisted that “public policy in Pakistan has to focus on public education” in order to prevent those students from slipping through the cracks. The problem, he added, was that “the education that they are receiving is pretty bad. It really does not prepare them to be active participants in the workforce and contribute to the economic development of the country.”

Still, most of the experts sounded optimistic about Pakistan’s potential to mitigate some of the adverse effects associated with the near-doubling of the country’s population during the next 40 years. By starting to more openly address an issue that the government and the powerful Pakistani media have long preferred to ignore, they seemed to agree the country is taking a big step in dealing head-on with its looming demographic challenges.

“I don’t look at the Pakistani population as a burden, but rather as an asset,” remarked Burki. “But it has to be managed.”

Photo Credit: “School Girls Talk in Islamabad,” courtesy of flickr user Documentally. -

‘Dialogue Television’ Explores Pakistan’s Population Challenge

›It’s difficult to imagine a scenario for a stable and peaceful world that doesn’t involve a stable and peaceful Pakistan. The country is among the world’s most populous and is also home to the world’s second largest Muslim population, making it the only Muslim majority nuclear state. Its history has been characterized by periods of military rule, political instability, and regional conflicts. This week on dialogue host John Milewski explores the nation’s changing demographics and what they may tell us about near and long term prospects for this vital U.S. ally with guests Michael Kugelman, Zeba Sathar, and Mehtab Karim.

Watch above or on MHz Worldview.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Wilson Center’s Asia Program. Much of his recent research and programming focus has involved demographics in Pakistan. He is a regular contributor to Dawn, one of Pakistan’s major English language newspapers.

Zeba Sathar is Pakistan country director at the Population Council in Islamabad. Prior to joining the council, she was chief of research in demography at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics and a consultant with the World Bank.

Mehtab Karim is a distinguished senior fellow and affiliated professor with the School of Public Policy at George Mason University. Additionally, he is a senior research fellow at the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life, specializing in global Muslim demographics. Previously, he was a professor of demography at Aga Khan University in Karachi.

Note: A QuickTime plug-in may be required to launch the video. -

Defusing the Bomb: Overcoming Pakistan’s Population Challenge

›According to the UN’s latest mid-range demographic projections for Pakistan, the country’s population–currently about 185 million–will rise to 335 million by 2050. This explosive increase, however, represents the best-case scenario: Should fertility rates remain constant, the UN estimates this figure could approach 460 million. Such soaring population growth, coupled with youthful demographics, a dismal education system, high unemployment, and a troubled economy, pose great risks for Pakistan. Predictably, many observers depict Pakistan’s population situation as a ticking time bomb.

At the same time, some demographers contend that the country’s population profile can potentially bring great benefits to the country. If young Pakistanis can be properly educated and successfully absorbed into the labor force, such experts explain, then the country could experience a “demographic dividend” that boosts social well-being and sparks economic growth. On June 9, the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, Environmental Change and Security Program, and Comparative Urban Studies Project, along with the Karachi-based Fellowship Fund for Pakistan, hosted a day-long conference to examine both the challenges and opportunities of Pakistan’s demographics, and to discuss how best to tackle the former and maximize the latter.

Pakistan at a Crossroads

In her opening address, Zeba A. Sathar of the Population Council declared that Pakistan is “at a crossroads.” Demography will play a key role in determining the country’s future trajectory, she said, yet there is presently little discussion about demographics in Pakistan. Sathar’s presentation traced Pakistan’s recent demographic trends. Despite its high population growth, Pakistan’s fertility rates have actually been in decline since the early 1990s–a fact that Sathar attributed to progressively higher ages at marriage (for both men and women), but also to the “reality” of abortion. However, Pakistan’s pace of fertility decline has slowed in the last few years–a consequence, Sathar argued, of Islamabad’s failure to promote social development (particularly education) and of the international donor community’s prioritizing of HIV/AIDS funding over that of family planning since 2000. Sathar concluded that achieving Pakistan’s “demographic dreams” will require more educational and employment opportunities (particularly for women) and better access to family planning in rural areas.

In the following panel, Wilson Center Senior Scholar Shahid Javed Burki noted the long-standing failure of demographers and economists in Pakistan to work together on the country’s population issues. This failure, Burki asserted, has resulted in poor choices and bad policy. He also criticized officials and scholars for being reactive in their population proposals, rather than proactive. Burki emphasized that good policy choices can produce favorable results. If, for instance, the population policies launched in Pakistan’s early decades had been sustained to the present, the country today would have 30 million fewer people. Similarly, had Pakistan followed the Bangladeshi approach and concentrated on the economic empowerment of women, today there would be more than 40 million fewer Pakistanis. Good policies matter, Burki repeatedly asserted, and Pakistan’s large and growing population, if dealt with wisely, can be an asset rather than a burden.

Development Through the Bangladeshi Model and Education

Like Burki, Yasmeen Sabeeh Qazi of the Packard Foundation pointed to Bangladesh as a relative success story. She highlighted Bangladesh’s reproductive health services system, which has served to increase the health of Bangladeshis and reduce their poverty. Indonesia and Iran, whose fertility rates are one-half Pakistan’s, provide other examples in the Muslim world where official policy has made a significant difference. Qazi’s presentation emphasized the linkages between family planning, reproductive health, and development. Noting that one-third of pregnancies in Pakistan are unplanned, she underscored the correlation between smaller family size and higher gross national income. She urged the government to fashion a population policy that expands access to reproductive health services, strengthens the health system generally, promotes education (especially for girls), and creates more jobs.

Moeed Yusuf of the U.S. Institute of Peace examined the prospects for radicalization of Pakistan’s youth. Pakistan’s stratified education system, Yusuf cautioned, is not training productive, employable members of society. Only graduates of elite private schools or of foreign schools are prepared for the economy of the 21st century. Meanwhile, the economy is not producing the quality jobs the young expect, leading to an “expectation-reality disconnect” that fosters not only un- or underemployment, but also anger and alienation. Moreover, the state, by deliberately cultivating the ultra-right elements in Pakistani society who most want to radicalize the country’s youth, is part of the problem. Still, Yusuf added, echoing the hopefulness of other speakers, it is not too late. These disturbing trends can be reversed, with help from outside friends like the United States, which, Yusuf counseled, should focus on assisting Pakistan’s education system, support rural private schools, and allow more Pakistani students to study in the United States.

Plugging Public Sector Holes with Private Initiatives

Saba Gul Khattak focused her luncheon address on the work of the Pakistan government’s Planning Commission, of which she is a member. In recent years, Pakistan’s population programs have been devolved from the federal to the provincial and sub-provincial levels. This decentralization, she averred, has opened the way for a genuine reform agenda. But it has also contributed to a situation where no one at the federal level feels any “ownership” over the country’s population programs. Implementation has always been the most vulnerable point in the policy process–and the lack of “ownership” only accentuates this problem today. Khattak emphasized the linkages between population, health, education, and development. Today, she asserted, children are seen by their parents as a source of old age security. Only when the government fills this void through the establishment of an effective social security structure will Pakistan be able to reduce its fertility rates. Development must accompany a truly effective population program.

In the afternoon panel, Sohail Agha of Population Services International discussed the role of the private sector in family planning in Pakistan. He argued that this sector has made a “substantial contribution” to Pakistan’s increased use of condoms: In 2006-07, a period when condom use spiked by nearly 8 percent, about 80 percent of this increase was covered by contraceptives provided by the private sector. Additionally, he noted that a 2009 survey found that urban Pakistanis exposed to social marketing campaigns about condom utilization increased their use of the contraceptive by 10 percent. Furthermore, he described private-sector-led health financing plans for women’s fertilization–a method of contraception that, like condoms, has increased over the last 30 years in Pakistan.

Engaging Youth and Political and Religious Leaders

Shazia Khawar of the British Council discussed the “Next Generation” report, a 2009 Council study about Pakistan’s youth. The report, based on a survey of 1,500 young people across both rural and urban Pakistan, concludes that young Pakistanis are deeply disillusioned about their country and its institutions, with three-quarters of those surveyed saying they regard themselves as “primarily” Muslims, not Pakistanis. The report’s “critical point,” said Khawar, is that Pakistani youth participation in policy development is nonexistent. To this end, the British Council has spearheaded several initiatives to engage the country’s youth in Pakistani politics and to spark dialogue between young Pakistanis and policymakers. Khawar concluded, however, that success is possible only if Pakistan’s top political leaders “pledge themselves to this agenda.”

Mehtab S. Karim of the Pew Research Center offered a comparative perspective, discussing demographics in the broader Muslim world, with particular emphasis on Bangladesh and Iran. Why, he asked, has Pakistan experienced less fertility decline than most of its fellow Muslim-majority nations? He suggested that the answer lies in the failure of Pakistan’s political and religious leaders to make early and sustained commitments to family planning. In Bangladesh, he explained, the country’s very first government made lower population growth rates a “prime goal.” And in Iran, spiritual leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa in support of contraceptive use soon after the Islamic Revolution. Yet in Pakistan, according to Karim, religious figures have consistently opposed Islamabad’s family planning efforts, and the government has proven unwilling or unable to combat this resistance.

Scott Radloff of USAID discussed his agency’s family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH) projects in Pakistan. FP/RH aid to Pakistan was largely cut off during much of the 1990s due to the Pressler Amendment–a 1985 modification to the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act that banned most U.S. military and economic assistance to Pakistan unless the U.S. president certified that Pakistan had no nuclear weapons. President George W. Bush waived this prohibition in 2001, and since then USAID FP/RH assistance has risen to nearly $45 million. Current interventions focus on strengthening services within Pakistan’s Ministry of Health and Ministry of Population Welfare; improving contraceptive supplies and logistics; expanding community-based services; and increasing awareness and commitment, including among religious leaders.

Participants concurred that Pakistan’s demographic situation is fraught with risk. Yet they also highlighted a series of hopeful signs. Yusuf noted the absence of an “imminent” danger of youth radicalization; Khawar pointed to the testimonies of “many young leaders determined to do their part” that flow from the “Next Generation” report; and both Karim and Qazi cited Bangladesh and Iran as proof that successful family planning programs are possible even in countries marked by deep poverty or conservative Islam. The presenters were also in accord about the necessary policies moving forward: more extensive family planning and reproductive health services, better education, and more job opportunities (particularly for women). At the same time, speakers repeatedly underscored the profound challenges facing the implementation of such policies. Still, for all the talk about major obstacles and challenges, there was recognition that more modest and simple steps can be taken as well–such as promoting more discussion about demographics within Pakistan, and especially among experts from different disciplines.

Michael Kugelman is program associate and Robert M. Hathaway is director of the Wilson Center’s Asia Program.

Photo credit: Traffic in downtown Karachi, courtesy Flickr user Ali Adnan Qazalbash. -

Women Deliver: Real Solutions for Reproductive Health and Maternal Mortality

›The landmark Women Deliver conference, which concluded last week, reinvigorated the global health community’s commitment to improve reproductive health at both the grassroots and global levels. Providing a major boost was the Gates Foundation’s announcement that it will commit an additional $1.5 billion over the next five years to support maternal and child health, family planning, and nutrition programs in developing countries.

“We haven’t tried hard enough,” said Gates Foundation co-founder Melinda Gates. “Most maternal and newborn deaths can be prevented with existing, low-cost solutions.” Examples of these efficient and effective solutions were presented at the three-day conference’s dozens of panels on a wide range of issues, including climate change, contraceptive commodities, fistula, gender inequities, adolescent family planning, communications and technology, and much more.

Empowering Young Girls to Access Family Planning

“When we speak about adolescents we typically think of prevention. However, we must also think about providing access to safe abortions and supporting young women who want to be mothers and empower young women to make choices,” said Katie Chau, a consultant at International Planned Parenthood Federation.

In Nigeria, “there is not much attention on adolescent sexual and reproductive health, even though a majority of rapes occur before the age of 13, and the rate of teenage pregnancy and abortions is high,” said Bene Madunagu, chair of the Girls’ Power Initiative (GPI) in Nigeria. GPI teaches girls about their rights to make decisions, including those regarding sex and reproductive health, as well as improving their critical thinking skills, self-esteem, and body image. “Girls develop critical consciousness and question discriminatory practices, while also learning about the legal instruments to take up their concerns,” he said.

Sadaf Nasim of Rahnuma Family Planning said child marriages are common in his country, Pakistan. “Marriage is an easy solution for poor families. Once a girl is married she is no longer the responsibility of the family,” he explained.

While laws in Pakistan and other parts of the developing world condemn child marriage, the prevalence of child marriage remains high: 49 percent of girls are married by age 18 in South Asia, and 44 percent in West and Central Africa. Nasim said birth registration at the local and national levels should be improved to prevent parents from manipulating their daughter’s age.

In Kyrgyzstan, “community-based efforts worked to galvanize media attention and disseminate information to demonstrate the need for improved adolescent family planning,” said Tatiana Popovitskaya, a project coordinator with Reproductive Health Alliance of Kyrgyzstan. Such community-based approaches use grassroots education to mobilize community leaders, which is a critical step in overcoming child marriage and other harmful traditions.

Cell Phones and Maternal Health

“There is a lot of information being collected, but it is not necessarily going where it needs to because of fragmentation,” said Alison Bloch, program director at mHealth Alliance. In developing countries, the people most in need are often the most isolated, but mobile technology is emerging as a way to bridge the gaps.

According to a recent report by mHealth Alliance, 64 percent of mobile phone users live in developing countries and more than half of people living in remote areas will have mobile phones by 2012. The potential for improving global health with cell phones and PDAs is significant, and can address a wide range of health issues, such as human resource shortages and information sharing problems between clinics and hospitals.

“Mobile technology provides benefits to individuals, institutions, caregivers, and the community. It reduces travel time and costs for the individual, improves efficiency of health service delivery, and streamlines information to health workers to reduce maternal mortality,” said Elaine Weidman, vice president of sustainability and corporate responsibility at Ericsson.

“Mobile technology is the most rapidly adopted technology in history and represents an existing opportunity to reach the un-reached,” said Fabiano Teixeira da Cruz, a program manager for the Inter-American Development Bank, speaking of the benefits of using mobile technology to train field-based healthcare workers in Latin America.

While mobile phones are indeed reaching parts of the world not currently equipped with quality healthcare, the lack of systematic coordination and infrastructure at the district and regional levels must also be addressed, as highlighted during a recent Wilson Center event, Improving Transportation and Referral for Maternal Health.

Read about our first impressions of Women Deliver 2010 here.

Calyn Ostrowski is program associate with the Wilson Center’s Global Health Initiative

Photo credit: Woman and child in South African AIDS clinic, courtesy Flickr user tcd123usa. -

New Security Challenges in Obama’s Grand Strategy

›June 4, 2010 // By Schuyler NullPresident Obama’s National Security Strategy (NSS), released last week, reinforces a commitment to the whole of government approach to defense, and highlights the diffuse challenges facing the United States, including international terrorism, globalization, and economic upheaval.

Following the lead of the Quadrennial Defense Review released earlier this year, the NSS for the first time since the Clinton years prominently features non-traditional security concerns such as climate change, population growth, food security, and resource management:Climate change and pandemic disease threaten the security of regions and the health and safety of the American people. Failing states breed conflict and endanger regional and global security… The convergence of wealth and living standards among developed and emerging economies holds out the promise of more balanced global growth, but dramatic inequality persists within and among nations. Profound cultural and demographic tensions, rising demand for resources, and rapid urbanization could reshape single countries and entire regions.

By acknowledging the myriad causes of instability along with more “hard” security issues such as insurgency and nuclear weapons, Obama’s national security strategy takes into account the “soft” problems facing critical yet troubled states – such as Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and Somalia – which include demographic imbalances, food insecurity, and environmental degradation.

Not surprisingly, Afghanistan in particular is highlighted as an area where soft power could strengthen American security interests. According to the strategy, agricultural development and a commitment to women’s rights “can make an immediate and enduring impact in the lives of the Afghan people” and will help lead to a “strong, stable, and prosperous Afghanistan.”

The unique demographic landscape of the Middle East, which outside of Africa has the fastest growing populations in the world, is also given intentional consideration. “We have a strategic interest in ensuring that the social and economic needs and political rights of people in this region, who represent one of the world’s youngest populations, are met,” the strategy states.

Some critics of that strategy warn that the term “national security” may grow to encompass so much it becomes meaningless. But others argue the administration’s thinking is simply a more nuanced approach that acknowledges the complexity of today’s security challenges.

In a speech on the strategy, Secretary of State Clinton said that one of the administration’s goals was “to begin to make the case that defense, diplomacy, and development were not separate entities either in substance or process, but that indeed they had to be viewed as part of an integrated whole and that the whole of government then had to be enlisted in their pursuit.”

Compare this approach to President Bush’s 2006 National Security Strategy, which began with the simple statement, “America is at war” and focused very directly on terrorism, democracy building, and unilateralism.

Other comparisons are also instructive. The Bush NSS mentions “food” only once (in connection with the administration’s “Initiative to End Hunger in Africa”) and does not mention population, demography, agriculture, or climate change at all. In contrast, the 2010 NSS mentions food nine times, population and demography eight times, agriculture three times, and climate change 23 times – even more than “intelligence,” which is mentioned only 18 times.

For demographers, development specialists, and environmental conflict specialists, the inclusion of “new security” challenges in the National Security Strategy, which had been largely ignored during the Bush era, is a boon – an encouraging sign that soft power may return to prominence in American foreign policy.

The forthcoming first-ever Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review by the State Department will help flesh out the strategic framework laid out by the NSS. It is expected to provide more concrete policy for integrating defense, diplomacy, and development. Current on-the-ground examples like USDA embedding in Afghanistan, stepped-up development aid to Pakistan, and the roll-out of the administration’s food security initiative, “Feed the Future,” are encouraging signs that the NSS may already be more than just rhetoric.

Update: The Bush 91′ and 92’ NSS also included environmental considerations, in part due to the influence of then Director of Central Intelligence, Robert Gates.

Sources: Center for Global Development, CNAS, Los Angeles Times, State Department, USAID, White House, World Politics Review.

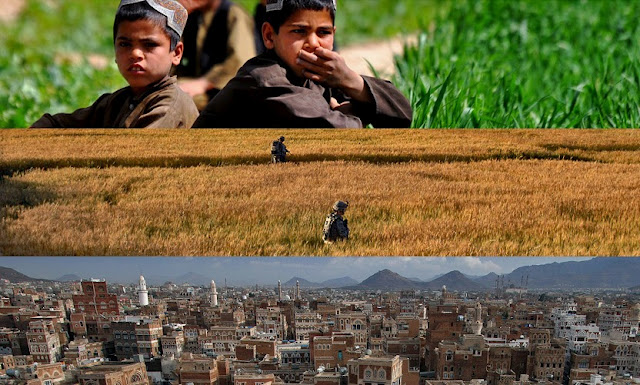

Photo Credit: “Human, Food, and Demographic Security” collage by Schuyler Null from “Children stop tending to the crop to watch the patrol” courtesy of flickr user isafmedia, “Combing Wheat” courtesy of flickr user AfghanistanMatters, and “Old Town Sanaa – Yemen 49” courtesy of flickr user Richard Messenger. -

Can Food Security Stop Terrorism?

›May 28, 2010 // By Schuyler NullUSAID’s “Feed the Future” initiative is being touted for its potential to help stabilize failing states and dampen simmering civil conflicts. Speaking at a packed symposium on food security hosted by the Chicago Council last week, USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah called food security “the foundation for peace and opportunity – and therefore a foundation for our own national security.”

-

Look Beyond Islamabad To Solve Pakistan’s “Other” Threats

›After years of largely being ignored in Washington policy debates, Pakistan’s “other” threats – energy and water shortages, dismal education and healthcare systems, and rampant food insecurity – have finally moved to the front burner.

For several years, the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Asia Program has sought to bring these problems to the attention of the international donor community. Washington’s new determination to engage with Pakistan on its development challenges – as evidenced by President Obama’s signing of the Kerry-Lugar bill and USAID administrator Raj Shah’s comments on aid to Pakistan – are welcome, but long overdue.

The crux of the current debate on aid to Pakistan is how to maximize its effectiveness – that is, how to ensure that the aid gets to its intended recipients and is used for its intended purposes. Washington will not soon forget former Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf’s admission last year that $10 billion in American aid provided to fight the Taliban and al-Qaeda was instead diverted to strengthen Pakistani defenses against archrival India.

What Pakistani institutions will Washington use to channel its aid monies? In recent months, the U.S. government has considered both Pakistani NGOs and government agencies. It is now clear that Washington prefers to work with the latter, concluding that public institutions in Pakistan are better equipped to manage large infusions of capital and are more sustainable than those in civil society.

This conclusion is flawed. Simply putting all its aid eggs in the Pakistani government basket will not improve U.S. aid delivery to Pakistan, as Islamabad is seriously governance-challenged.

Granted, Islamabad is not hopelessly corrupt. It was not in the bottom 20 percent of Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index (Pakistan ranked 139 out of 180), and enjoyed the highest ranking of any South Asian country in the World Bank’s 2010 Doing Business report.

At the same time, the Pakistani state repeatedly fails to provide basic services to its population – not just in the tribal areas, but also in cities like Karachi, where 30,000 people die each year from consuming unsafe water.

Where basic services are provided, Islamabad favors wealthy, landed, and politically connected interests over those of the most needy – the very people with the most desperate need for international aid. Last year, government authorities established a computerized lottery that was supposed to award thousands of free tractors to randomly selected small farmers across Pakistan. However, among the “winners” were large landowners – including family members of a Pakistani parliamentarian.

Working through Islamabad on aid provision is essential. However, the United States also needs to diversify its aid partners in Pakistan.

For starters, Washington should look within civil society. This rich and vibrant sector is greatly underappreciated in Washington. The Hisaar Foundation, for example, is one of the only organizations in Pakistan focusing on water, food, and livelihood security.

The country’s Islamic charities also play a crucial role. Much of the aid rendered to health facilities and schools in Pakistan comes from Muslim welfare associations. Perhaps the most well-known such charity in Pakistan – the Edhi Foundation – receives tens of millions of dollars each year in unsolicited funds.

Washington should also be targeting venture capital groups. The Acumen Fund is a nonprofit venture fund that seeks to create markets for essential goods and services where they do not exist. The fund has launched an initiative with a Pakistani nonprofit organization to bring water-conserving drip irrigation to 20,000-30,000 Pakistani small farmers in the parched province of Sindh.

Such collaborative investment is a far cry from the opaque, exploitative foreign private investment cropping up in Pakistan these days – particularly in the context of agricultural financing – and deserves a closer look.

With all the talk in Washington about developing a strategic dialogue with Islamabad and ensuring the latter plays a central part in U.S. aid provision to Pakistan, it is easy to forget that Pakistan’s 175 million people have much to offer as well. These ample human resources – and their institutions in civil society – should be embraced and be better integrated into international aid programs.

While Pakistan’s rapidly growing population may be impoverished, it is also tremendously youthful. If the masses can be properly educated and successfully integrated into the labor force, Pakistan could experience a “demographic dividend,” allowing it to defuse what many describe as the country’s population time bomb.

A demographic dividend in Pakistan, the subject of an upcoming Wilson Center conference, has the potential to reduce all of Pakistan’s threats – and to enable the country to move away from its deep, but very necessary, dependence on international aid.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Photo Credit: Water pipes feeding into trash infected waterway in Karachi, courtesy Flickr user NB77. -

Family Planning in Fragile States

›

“Conflict-affected countries have some of the worst reproductive health indicators,” said Saundra Krause of the Women’s Refugee Commission at a recent Wilson Center event. “Pregnant women may deliver on the roadside or in makeshift shelters, no longer able to access whatever delivery plans they had. People fleeing their homes may have forgotten or left behind condoms and birth control methods.”

Showing posts from category Pakistan.