Showing posts from category China.

-

The 10 Most Popular Posts of 2008

›From climate change to coltan, poverty to population, and water to war: These are the 10 most popular New Security Beat stories of the year. Thanks for your clicks, and we’ll see you in 2009!

1. Desertification Threatening China’s Human, Economic Health

2. PODCAST – Climate Change and National Security: A Discussion with Joshua Busby, Part 1

3. In the Philippines, High Birth Rates, Pervasive Poverty Are Linked

4. Climate Change Threatens Middle East, Warns Report

5. Population, Health, Environment in Ethiopia: “Now I know my family is too big”

6. Guest Contributor Colin Kahl on Kenya’s Ethnic Land Strife

7. Coltan, Cell Phones, and Conflict: The War Economy of the DRC

8. “Bahala na”? Population Growth Brings Water Crisis to the Philippines

9. Population Reference Bureau Releases 2008 World Population Data Sheet

10. Guest Contributor Sharon Burke on Climate Change and Security -

Food Production Goes Global, Sparking Land Grabs in Developing World

›December 8, 2008 // By Will Rogers As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

From the Persian Gulf to East Asia, governments and international companies alike have been lobbying developing countries in Africa and Asia to produce grain for food and alternative energy. The Guardian reported on November 22nd that Qatar recently leased 40,000 hectares of Kenyan farmland in return for funding a £2.4 billion port on the island of Lamu, a popular tourist site just off the Kenyan coast. The Saudi Binladen Group is said to be finalizing a deal with Indonesia to lease land for basmati rice production, while other Arab investors, including the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, have bought land rights for agricultural production in Sudan and Pakistan. Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has been “courting would-be Saudi investors,” despite his country’s own deplorable food insecurity and chronic malnutrition.

Meanwhile, the Telegraph reported that South Korea’s Daewoo Logistics has been working to secure a 99-year lease for 3.2 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar that it will use to “grow 5 million metric tons of maize a year and 500,000 tons of palm oil” to use as biofuel in South Korea. The company says it expects to pay almost nothing besides infrastructure costs and employment training in return for its use of the land. Despite Madagascar’s rapid population growth and pervasive food insecurity, the deal, if signed, will allow the South Korean company to lease approximately half of the current arable farmland on the island state.

In an effort to combat a freshwater shortage, China has secured an agreement with Laos for a 50-year lease of 1,600 hectares of land in return for funding a new sports complex in Vientiane for the 2009 Southeast Asian Games. And with only 8 percent of the world’s arable land and more than one-fifth of the world’s population to feed, China continues to encourage its businesses to go outside China to produce food, looking to developing countries in Africa and Latin America.

Jacques Diouf, director-general of the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, recently warned that these deals are a “political hot potato” that could prove devastating to the developing world’s own food supply, as several of these states already face severe food insecurity. Diouf has expressed concern that these deals could breed a “neo-colonial” agricultural system that would have the world’s poorest and most malnourished feeding the rich at their own expense.

And with land rights a contentious issue throughout the developing world—including in Haiti, Kenya, and Sudan, for instance—these agreements could spark civil conflict if governments and foreign investors fail to strike equitable deals that also benefit local populations. “Land is an extremely sensitive thing,” warns Steve Wiggins, a rural development expert at the Overseas Development Institute. “This could go horribly wrong if you don’t learn the lessons of history” and attempt to minimize inequality.

As food prices continue to climb, more and more countries are likely to scramble to gain access to the developing world’s arable land. Without land-use agreements that ensure a host country’s domestic food supply is secure before its foreign investor’s, long-term sustainable development could be set back decades, something impoverished developing countries simply cannot afford.

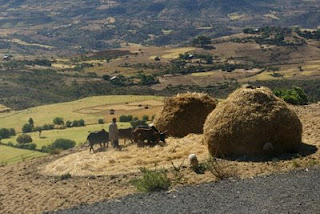

Photo: A man threshing in Ethiopia. Long plagued by acute food insecurity, Ethiopia’s arable land is sought by more-developed countries to ensure the stability of their own food stocks. Courtesy of Flickr user Eileen Delhi. -

Climate Change and Security

› Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”

Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”

From July 27-30, 2008, my organization, the Center for a New American Security, led a consortium of 10 scientific, private, and public policy organizations in an experiment to answer this particular “what if.” The experiment, a climate change “war game,” tested what a change in U.S. position might mean in 2015, when the effects of climate change will likely be more apparent and the global need to act will be more urgent. The participants were scientists, national security strategists, scholars, and members of the business community from China, Europe, India, and the Americas. The variety was intentional: We hoped to leverage a range of expertise and see how these different communities would interact to solve problems.

Climate change may seem a strange subject for a war game, but one of our primary goals was to highlight the ways in which global climate change is, in fact, a national security issue. In our view, climate change is highly likely to provoke conflict—within states, along borders as populations move, and, down the line, possibly between states. Also, the way the military calculates risk and engages in long-term planning lends itself to planning for the climate change that is already locked in (and gives strategic urgency to cutting emissions and preventing future climate change).

The players were asked to confront a near-term future in 2015, in which greenhouse gas emissions have continued to grow and the pattern of volatile and severe weather events has continued. The context of the game was an emergency ad-hoc meeting of the world’s top greenhouse gas emitters in 2015—China, the European Union, India, and the United States—to consider future projections (unlike most war games, the projections were real; Oak Ridge National Laboratory analyzed regional-level Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change data from the A1FI series specifically for the game). The “UN Secretary-General” challenged the top emitters to come up with an agreement to deal with increased migration resulting from climate change; resource scarcity; disaster relief; and drastic emissions cuts.

Although the players did reach an agreement, which is an interesting artifact in itself, that was not really the point. The primary objective was to see how the teams interacted and whether we gained any insight into our current situation. While we’re still processing all of our findings, I certainly came away with an interesting answer to that “what if” question. If the United States had been forward-leaning on climate change these past eight years, taking action at home and proposing change internationally, it would have made a difference, but only to a point. As important as American leadership will be on this issue, it is Chinese leadership—or followership—that will be decisive. And it is going to be very, very difficult—perhaps impossible—for China to lead, at least under current circumstances. The tremendous growth of China’s economy has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but there are hundreds of millions more still to be lifted. The stark reality is that China will be fueling that economic growth with coal, oil, and natural gas—just as the United States did in the 20th century—unless and until there is a viable alternative.

If the next administration hopes to head off the worst effects of global climate change, it will not only have to find a way to cut greenhouse gas emissions at home, it may well have to make it possible for China to do so, too.

Sharon Burke is a national security expert at the Center for a New American Security, where she focuses on energy, climate change, and the Middle East.

Photo: The U.S., EU, and Chinese simulation teams in negotiations. Courtesy of Sharon Burke. -

Weekly Reading

›Eighty-two percent of experts surveyed by Foreign Policy and the Center for American Progress for the 2008 Terrorism Index said that the threat posed by competition for scarce resources is growing, a 13 percent increase over last year.

China Environment Forum Director Jennifer Turner maintains that China is facing “multiple water crises” due to pollution and rising demand in an interview with E&ETV;.

The Population Reference Bureau has two new articles examining the nexus between population and environment. One explores the relationship between forest conservation and the growth of indigenous Amazonian populations, while the other provides an excellent examination of population’s role in the current food crisis, with a special emphasis on East Africa.

Ethiopia’s rapid population growth “has accelerated land degradation, as forests are converted to farms and pastures, and households use unsustainable agricultural methods to eke out a living on marginal land,” writes Ruth Ann Wiesenthal-Gold in “Audubon on the World Stage: International Family Planning and Resource Management.” Wiesenthal-Gold attended a November 2007 study tour of integrated population, health, and environment (PHE) development programs in Ethiopia sponsored by the Audubon Society and the Sierra Club. -

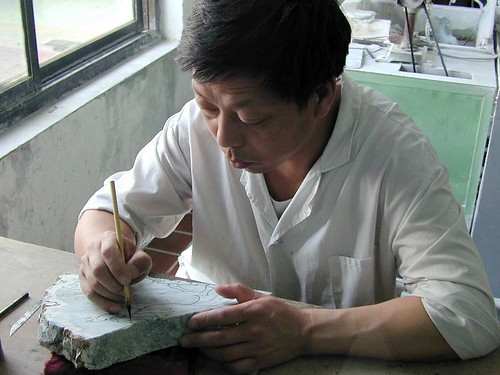

2008 Olympics Fuels Burma’s Oppressive Jade Trade

›August 8, 2008 // By Daniel Gleick Four billion people are expected to watch the opening ceremonies of the Olympics today. But what many people may not know is that in an attempt to highlight Chinese heritage, the medals given to victorious Olympic athletes over the next several weeks will include jade—much of which is mined in terrible conditions in neighboring Burma. Although the Beijing Organizing Committee has publicly stated that the medals and officially licensed products are being made with jade from China’s Qinghai Province, not jade from Burma, Blood Jade: Burmese Gemstones & the Beijing Games, a new report by 8-8-08 for Burma and the All Kachin Students and Youth Union maintains that the “showcasing of jade on the world stage will further escalate the growth in demand.

Four billion people are expected to watch the opening ceremonies of the Olympics today. But what many people may not know is that in an attempt to highlight Chinese heritage, the medals given to victorious Olympic athletes over the next several weeks will include jade—much of which is mined in terrible conditions in neighboring Burma. Although the Beijing Organizing Committee has publicly stated that the medals and officially licensed products are being made with jade from China’s Qinghai Province, not jade from Burma, Blood Jade: Burmese Gemstones & the Beijing Games, a new report by 8-8-08 for Burma and the All Kachin Students and Youth Union maintains that the “showcasing of jade on the world stage will further escalate the growth in demand.

Despite being internationally and internally reviled, Burma’s ruling military junta has been able to maintain its grip on power by controlling the country’s rich natural resources. Burma exports many types of gems, all of which the junta requires be sold through government auctions, where it takes a cut of the profits. BusinessWeek reported that Burma’s official 2006 jade exports totaled $433.2 million, or 10 percent of the country’s total exports. Official tallies are often unreliable, however, and the black market further obscures the true figures.

“In the mining areas, the companies make their own laws,” says a Burmese citizen quoted in the report. Blood Jade tells of mining companies—sometimes with official military support—beating, torturing, and even killing miners who dig through mine waste for discarded stones or make mistakes on the job. “Jadeite production comes at significant costs to the human rights and environmental security of the people living in Kachin state,” says the report. “Land confiscation and forced relocation are commonplace and improper mining practices lead to frequent landslides, floods, and other environmental damage. Conditions in the mines are deplorable, with frequent accidents and base wages less than US$1 per day.”

In an attempt to keep workers on duty for longer hours and to suppress rebellion, the Burmese government has encouraged drug sales and use. The economic situation is so desperate that many women are forced into the sex trade, which the government also condones. The combination of prostitution and drug use has led to disastrous HIV/AIDS rates. “Today,” Blood Jade reports, “four prefectures in Yunnan Province are regarded as having ‘generalized HIV epidemics.’”

Yet despite the misery they cause, jade and other gems are not even the largest single source of income for Burma’s rulers. According to a 2007 article from Foreign Policy, two other resources rate higher: natural gas and the tropical hardwood teak, which is so valuable that it has “perpetuated violent conflicts among the country’s many fractious ethnic groups.”

Several groups have organized campaigns urging people not to buy jade products, but it is unclear what impact they will have on the trade. Following the junta’s crackdown on anti-government protests by Buddhist monks in November 2007, a representative of Kam Wing Cheong Jewelry in China told BusinessWeek: “We will not stop purchasing stones in Burma because of the political situation. The political chaos did not start with the junta; the country has been plagued by the conflicts with ethnic minorities for years. This is totally out of our control.”

Photo: Man working in a jade factory in China. Courtesy of Flickr user maethlin -

Weekly Reading

›“Women are key to the development challenge,” says Strategies for Promoting Gender Equity in Developing Countries, but “gender mainstreaming has been associated with more failures than gains.” Detailing findings from an April 2007 conference co-sponsored by the Wilson Center and the Inter-American Foundation, the report calls for a redesigned approach operating on multiple fronts. Blogging about the report, About.com’s Linda Lowen dubs the gap between women and men in developing countries a “Grand Canyon-like divide” compared to the “crack in the sidewalk” faced by Western women.

A Council on Foreign Relations backgrounder on Angola—now Africa’s leading oil producer—tackles the familiar paradox of extreme poverty in resource-rich countries. Burdened by “an opaque financial system rife with corruption,” Angola’s leaky coffers are filling up with Chinese currency. As Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos put it, “China needs natural resources, and Angola wants development.” FastCompany.com’s “Special Report: China In Africa” criticizes the overwhelming Chinese presence in Africa: “The sub-Sahara is now the scene of one of the most sweeping, bare-knuckled, and ingenious resource grabs the world has ever seen.”

In Scientific American’s “Facing the Freshwater Crisis,” Peter Rogers writes that the demands of increasing population, along with increasingly frequent droughts due to climate change, signal rough waters ahead, and calls for major infrastructure investments to prevent catastrophe. Closer to home, Circle of Blue reports on a new era of water scarcity in the United States, and director Jim Thebaut’s documentary “Running Dry: The American Southwest” takes a look at the hard-hit region.

Pastoralists are socially marginalized in many countries, making them highly vulnerable to climate change despite their well-developed ability to adapt to changing conditions, reports the International Institute for Environment and Development in “Browsing on fences: Pastoral land rights, livelihoods and adaptation to climate change.” The paper notes that the “high rate of development intervention failure” has worsened the situation, and calls for giving pastoralists “a wider range of resources, agro-ecological as well as socio-economic,” to protect them.

-

“Development in Reverse”: ‘International Studies Quarterly’ Article Links Natural Disasters, Violence

›May 20, 2008 // By Sonia SchmanskiAlthough numerous research projects have found that environmental change can contribute to conflict “through its impact on social variables such as migration, agricultural and economic decline, and through the weakening of institutions, in particular the state,” very few analysts have systematically addressed the relationship between natural disasters and violent civil conflict, write Philip Nel and Marjolein Rightarts in “Natural Disasters and the Risk of Violent Conflict,” published in the March 2008 issue of International Studies Quarterly (subscription required). Criticizing political scientists’ tendency to diminish the importance of geography and environmental factors in assessing violence, they argue that it has become critically important to “correct this oversight.”

Recent events indicate that this attention is overdue. On May 2, Cyclone Nargis began its devastating journey through Myanmar. The latest UN estimates put the death toll at somewhere between 70,000 and 100,000. On May 12, a 7.9-magnitude earthquake struck China’s Sichuan Province (incidentally, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes top Nel and Rightarts’ list of the disasters most likely to lead to violence). Official death toll estimates currently stand at 40,000, but are likely to continue to increase. While the Chinese government has been praised both at home and abroad for the speed and scale of its response, Burma’s ruling military junta has been roundly condemned for delaying the arrival of international humanitarian assistance. It remains to be seen whether the junta’s controversial response will lead to popular rebellion among the Burmese people.

Low- and middle-income countries with high levels of inequality are most susceptible to the violence caused by natural disasters, write Nels and Rightarts. Natural disasters create openings for violent civil conflict by reducing state capacity while simultaneously increasing demands upon the state. The scramble for limited resources in the wake of a natural disaster can easily devolve into widespread violence.

“Given the dire predictions that natural disasters are set to become more frequent in the near future” due to climate change, Nel and Rightarts conclude, “conflict reduction and management strategies in the twenty-first century simply have to be more attuned to the effects of natural disasters than they have been up to now.” -

Environmental Security Heats Up ISA 2008

›May 9, 2008 // By Meaghan ParkerAfter a few years left out in the cold, environmental security came home to a warm welcome at this year’s International Studies Association conference in San Francisco, drawing large crowds to many star-studded panels. Water, climate, energy, and AFRICOM were hot topics, and the military/intelligence communities were out in force. Many of the publishers indicated they were seeking to acquire titles or journals on environmental security, given the scarcity of books on the topic currently in the works. Demographic security even got a few shout-outs from well-placed supporters.

Climate change and energy security panels dominated the program. Chaired by the National Intelligence Council’s Mathew Burrows, “Militarization of Energy Security” featured contributors to the edited volume forthcoming from Daniel Moran and James Russell of the Naval Postgraduate School—including original resource conflict gadfly Michael Klare, who claimed that lack of oil itself isn’t the problem, but that efforts to extract less accessible supplies would provoke violence in places like Nigeria, Venezuela, and Siberia. The intense discussion contrasted the approaches of China and the United States to ensuring energy security; Moran pointed out that China sent “bankers and oilmen” into Africa, whereas the United States created AFRICOM. “If the Chinese had created a military command in Africa, there wouldn’t be a dry seat in the Pentagon,” he added. David Hamon of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency observed that BP has a “security regime to protect their interests that would make a military blush.”

At “Climate Change, Natural Disasters, and Armed Conflict,” Clionadh Radleigh put the kibosh on the fearmongering predictions of waves of transnational “environmental refugees.” Similarly, Halvard Buhaug explored weaknesses in the reported links between climate change and conflict, calling for more rigorous research on this currently trendy topic. Christian Webersik’s research found links between negative rainfall and higher incidences of conflict in Somalia and Sudan, but he cautioned against using this relationship to predict climate-induced conflict.

A flood of panels on water, conflict, and cooperation took advantage of the conference’s West Coast location to call on water world heavies Aaron Wolf and Peter Gleick, who participated in a lively standing room-only roundtable chaired by ECSP’s Geoff Dabelko. Despite the obvious interest in the topic, publishers in the exhibit hall didn’t have much to offer on water and security.

AFRICOM drew some heat, especially from a panel of educators from military academies who explored peace parks and other “small-ball” approaches to conflict prevention. All the panelists were generally supportive of AFRICOM’s efforts to integrate nontraditional development work into the military’s portfolio—which, as discussant and retired U.S. Army Col. Maxie McFarland pointed out, it is already doing “by default” in Iraq and Afghanistan. McFarland cautioned, however, that “just because the Army can do it, doesn’t mean you want them to do it.” Air War College Professor Stephen Burgess predicted that the groundswell of climate change awareness would push the next president to include it in his or her National Security Strategy.

Rich Cincotta’s demographic security panel attracted significant interest—no small feat on the last day. The Department of Defense’s (DoD) Thomas Mahnken said that demographic trends and shocks are of “great interest to us in the government”—particularly forecasting that could identify what countries or regions the DoD should be worried about—particularly China and India (good thing demographer Jennifer Sciubba is on the case in his office).

The emphasis on prediction and forecasting stood out from the general trend of ISA panels, which mostly focus on analysis of current or past events. Mathew Burrows called for government and academia to “push the frontiers” on forecasting even further—particularly on the impacts of food security, water shortages, and environmentally induced migration.

Despite the warm, fuzzy feelings for environmental security, there were few panels devoted to general natural resource conflict, and none to post-conflict environmental peacebuilding (Michael Beevers contributed one of the few papers to explicitly address the topic).

What’ll be next year’s hot topics? Submit your proposals by May 30 for the 2009 ISA Annual Conference in New York City.

To download any of the papers mentioned above, visit the ISA’s online paper archive.

For more on ECSP at ISA, see “Environmental Security Is Hot Topic at the 2008 International Studies Association Conference.”

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world. Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”

Presidential administrations usually end with sepia retrospectives and long, adulatory lists of accomplishments. The present administration is unlikely to end this way, but it will certainly go out with many “what if” epitaphs. Near the top of my “what if” list is, “What if this administration had taken the threat of global climate change seriously and acted as though our future depended on cutting emissions and cooperating on adaptation?”