-

The Scoop on Development Reform

›The development reform picture became more complicated after a recent speech by Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Senator John Kerry (D-MA) and congressional testimony by Deputy Secretary of State for Management and Resources Jack Lew.

Revamping State and USAID

At a Brookings Institution speech (transcript) on May 21 entitled “Diplomacy and Development in the 21st Century,” Kerry laid out the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s plan for strengthening the civilian agencies that deal with these issues.

In the short term, Kerry favors the recruitment of more diplomatic and development professionals and a stronger emphasis on their training and education. He also expressed his desire to “untie the hands of our aid workers” by streamlining outdated regulations and rebalancing the relationship between Washington and the field.

“Over the long term, we need to take a close, hard look at exactly what we want our diplomatic and development institutions to achieve,” said Kerry. “We need to make sure that we give those people the resources they need to get where we have decided they must go.”

To meet these goals, he and Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN) will introduce two pieces of legislation: a Foreign Affairs Authorization Act and a foreign aid reform bill, which will serve as precursors to a more comprehensive overhaul of the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act next year, said Kerry.

A Power Grab by State?

On May 13, Lew testified on the FY2010 international affairs budget request (webcast; testimony), outlining five “smart power” funding objectives:

1. Build civilian capacities in State and USAID;

2. Promote long-term development and human security;

3. Enhance strategic multilateral and bilateral partnerships (e.g., with Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and Afghanistan);

4. Strengthen global security capabilities (e.g., nuclear non-proliferation); and

5. Maintain the resources to respond to urgent humanitarian needs.According to Lew, State’s approach to development will be both “top-down”—strengthening “the ability of governments to support just and capable institutions that meet the basic needs of their populations”—and “bottom-up”—partnering with civic groups to build human capacity to innovate, cooperate, and solve problems.

Lew indicated that State should coordinate multiple agencies’ efforts to address challenging, cross-sectoral problems. He said, “We must be able to look at a country, a function or an objective and be able to identify everything that the U.S. government is doing in that area—not just State.” For instance, he wants the State Department to lead “a whole-of-government process to design and implement a new food strategy.”

Lew’s testimony seems to indicate that State wants to oversee all of development policy, with no apparent role for the National Security Council (NSC). But it is not at all clear that State has the human and financial resources to coordinate all the other agencies involved in development. If State were granted this authority, the organizational implications would be immense.

At the NSC, development issues fall under the purview of Deputy National Security Adviser for International Economic Affairs Michael Froman, but he has many other issues on his agenda, including the G20 and the G8. I would be surprised if the NSC does not see this kind of overall coordination as part of its mandate. But there have been no public reactions to State’s grab for power.

At the same time, both Kerry and Congressman Howard Berman (D-CA), chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, see development reform as a major part of their portfolios. The State Department has strongly opposed Berman’s bill mandating that the administration produce a government-wide “National Development Strategy,” on the grounds that the responsibility for drafting such a document should be given to the State Department, and not (as it is now written) to the President. The future of Berman’s legislation is not clear, but Kerry also has indicated his desire for an overall strategy paper.

USAID Still Seeking Chief

Finally, USAID still lacks a director. The latest rumors in the blogosphere revolve around Dr. Paul Farmer, the renowned physician who founded Partners in Health, a major NGO focusing on global health. Farmer would be the first USAID administrator in recent years with extensive on-the-ground development experience, but I understand he has no experience with Washington bureaucracy (outside, perhaps, of the health arena). Furthermore, he is known more as a charismatic leader than as a manager.

Farmer would be an unconventional choice for running USAID, though there are conflicting opinions on whether he even wants the job. But if he does want it, he should ensure he had a deputy secretary rank, as well as authority over the Millennium Challenge Corporation, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, and other independent development programs. He also would need the funds and staff to completely revamp USAID to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

John W. Sewell is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the former president of the Overseas Development Council. ECSP published Sewell’s review of Trade, Aid and Security: An Agenda for Peace and Development in ECSP Report 13. -

Pakistan’s Daunting—and Deteriorating—Demographic Challenge

› Every day it seems the headlines bring new worries about the future of Pakistan. But among the many challenges confronting the nation—including a growing Taliban insurgency—one significant problem remains largely undiscussed: its rapidly expanding population.

Every day it seems the headlines bring new worries about the future of Pakistan. But among the many challenges confronting the nation—including a growing Taliban insurgency—one significant problem remains largely undiscussed: its rapidly expanding population.

Consider this: Pakistan’s population nearly quadrupled from 50 million in 1960 to 180 million today. It’s expected to add another 66 million people—nearly the entire population of Iran—in the next 15 years. UN projections predict that by the late 2030s, Pakistan will become the fourth most populous country in the world, behind India, China, and the United States.

And believe it or not, the demographic outlook for Pakistan got bleaker in recent weeks. The new medium-range UN projections for Pakistan’s total population have been raised to 335 million for 2050—45 million higher than the UN projection just two years ago. Why the change? Because birth rates aren’t falling as had been predicted—women in Pakistan have an average of four children—and unmet need for family planning remains high.

The case of education provides a snapshot of how these demographics affect Pakistan, from basic quality-of-life issues to the country’s overall stability. Even though the official literacy rate in Pakistan has increased from about 18 percent to 50 percent since 1970, the number of illiterate people has simultaneously jumped from 28 million to 48 million. The literacy rate for women stands at a shockingly low 35 percent.

As public schools have become increasingly overcrowded, more parents have turned to madrasas in an attempt to educate their children—or at least their sons. It’s no secret that some of Pakistan’s madrasas have ties to radical religious and terrorist-affiliated organizations.

So what does this portend for the future?

Even assuming large infusions of assistance from the United States, Pakistan’s public school system will become even more overwhelmed in the years ahead. Building enough schools and hiring enough teachers would be daunting in any country, let alone one facing as many challenges as Pakistan. It seems likely that enrollments in madrasas will swell, and more children will face a future with no schooling whatsoever. Clearly, this is not a recipe for a more stable and peaceful Pakistan.

Pakistan’s rapid population growth is not inevitable, however. A key driver is lack of access to family planning, which is symptomatic of the overall poor status of women and girls. More than 25 percent of Pakistani women have an unmet need for family planning—meaning the demand is clearly there—and nothing in the Koran prohibits its usage. In other majority-Muslim nations, such as Algeria, Bangladesh, and Iran, family planning has been prioritized and is widely used.

Unfortunately, family planning programs in Pakistan and many developing countries have suffered from both inattention and funding cuts in recent years. Traditionally, the United States has been a major source of funding and technical assistance, but since 1995, U.S. international family planning assistance has fallen 35 percent (adjusted for inflation), even as demand has increased.

Today, more than 200 million women—many of them in the most impoverished parts of the world—have an unmet need for family planning. In countries like Pakistan, the resulting rapid population growth makes it increasingly difficult to provide sufficient education, health care, housing, and employment—and depletes land, water, fisheries, and other vital natural resources.

The Obama administration recently proposed a new U.S. assistance strategy for Pakistan—and a key component is a significant increase in development and economic assistance. Let’s hope it will include an increase for family planning. It would be a wise investment in a brighter, more stable future—for Pakistan and for the world.

Tod Preston is vice president for U.S. government relations at Population Action International.

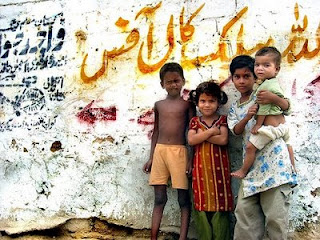

Photo: Children in Jinnah Colony, Karachi, Pakistan. Courtesy of Flickr user NB77. -

Climate Change and “Developed-Country Complacency Syndrome”

› While it is now widely acknowledged that environmental change, including climate change, could severely undermine security in the developing world, the implications for the developed world are just starting to be discussed. A sort of “developed-country complacency syndrome” has led many to assume that the main security problems for a country like the United States, such as waves of refugees or the need to intervene when other nations face disasters or conflicts, would be imported from abroad. Unfortunately, the United States is likely to face some fairly severe “Made in the USA” problems, as well.

While it is now widely acknowledged that environmental change, including climate change, could severely undermine security in the developing world, the implications for the developed world are just starting to be discussed. A sort of “developed-country complacency syndrome” has led many to assume that the main security problems for a country like the United States, such as waves of refugees or the need to intervene when other nations face disasters or conflicts, would be imported from abroad. Unfortunately, the United States is likely to face some fairly severe “Made in the USA” problems, as well.

For instance, as the economic stimulus package is rolled out, the United States is entering a historic period of new infrastructure construction. From a security perspective, this could help maintain stability, or it could be a disaster. What might make the difference is assessing how potential sites could be affected by environmental change. Transportation systems, defensive capabilities, agriculture, power generation, water supply, and more are all designed for the specific parameters of their physical environments—or, more often, the physical environments of the Victorian, Depression-era, or post-WWII periods in which they were originally built. That is why unplanned environmental change almost always has negative impacts.

In the case of a change in precipitation patterns, for example, drainage systems, reservoirs, and hydrological installations can all fail not because they were poorly engineered, but because they were engineered for different conditions. We are literally not designed for environmental change.

Current environmental impact assessments look almost exclusively at a structure’s impact on the environment. These assessments must now be expanded to include the other half of the equation: the impact of a changing environment on the structure. These sorts of “dual” assessments are essential. To put it bluntly, there is no point in building a zero-emissions house in a current or soon-to-be flood zone. However, this is exactly the sort of thing that is being proposed in areas of the U.S. Gulf Coast. We can avoid this by requiring these “dual” assessments when applying for insurance, planning permission, and/or government support.

Just as physical infrastructure is poorly prepared to deal with environmental change, so, too, is legal infrastructure. Very few regulations, international laws, and subsidies incorporate the effects of environmental change. At best, this renders them inadequate; at worst, it can create new vulnerabilities.

For instance, the U.S. government’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) can inadvertently contribute to putting people and infrastructure in harm’s way. When private insurers deem areas too risky to be eligible for coverage, the NFIP can step in and insure them, making it possible to build in areas that are current flood zones, as well as areas that may become ones as climate change causes sea levels to rise and storm surges to increase. Already in some areas the same homes have had to be rebuilt multiple times, in part with cash infusions from the NFIP.

There are other examples of developed-world agreements that may cause more damage than they prevent:- Water-sharing agreements, especially those based on a set amount of water, rather than percentage of actual flow, will become problematic as water levels alter dramatically.

- Fisheries-sharing agreements will be thrown into chaos as fish shift to other regions due to climate change and overfishing.

- Hydropower-sharing agreements will be a major problem, both for precipitation-fed systems and glacier regions, where there will be above-average flows as the glaciers melt, followed by droughts once the glaciers disappear.

Two of the things the developed world prides itself on—its physical and legal infrastructures—are both highly vulnerable to environmental change. However, the stimulus packages and the reassessment of global, regional, and national agreements caused by the financial crisis offer a valuable opportunity to ensure that the structures and mechanisms we are counting on to maintain our security do not end up undermining it.

Photo: Members of the Coast Guard Sector Ohio Valley Disaster Response Team and the Miami-Dade Urban Search and Rescue Team mark a house to show it has been searched for survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the U.S. Gulf Coast in 2005, revealed the vulnerability of U.S. infrastructure to natural disasters. Climate change could make hurricanes and other natural disasters more frequent and severe. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Tidewater Muse and Petty Officer Robert M. Reed.

Cleo Paskal is an associate fellow in Chatham House’s Energy, Environment, and Development Programme. She is the author of UK National Security and Environmental Change. -

Water’s Role in International Development

› A mark of a good event is that it generates further debate, questions, and ideas. “Water and International Development: A Dialogue,” a recent discussion at The Johns Hopkins University School for Advanced International Studies, was such an event. Geoff Dabelko, director of the Environment Change and Security Program at the Wilson Center, and Aaron Salzberg, special coordinator for water resources at the U.S. Department of State, went head-to-head to discuss water’s role in international development.

A mark of a good event is that it generates further debate, questions, and ideas. “Water and International Development: A Dialogue,” a recent discussion at The Johns Hopkins University School for Advanced International Studies, was such an event. Geoff Dabelko, director of the Environment Change and Security Program at the Wilson Center, and Aaron Salzberg, special coordinator for water resources at the U.S. Department of State, went head-to-head to discuss water’s role in international development.

The discussion between Dabelko and Salzberg touched upon many issues I ran into while trying to program Water for the Poor Act funding while working as a natural resources adviser for the Economic Growth Office at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) mission in Ghana. Once we received the funding, there was an intra-office debate among:- People who wanted to make drip-irrigation work we were already funding fit the Water for the Poor Act definition;

- People who thought the funds should be spent on a narrow set of water and sanitation interventions, such as borehole/latrine construction and water purification tablets; and

- People who thought the funds should be spent on the larger-scale water and sanitation infrastructure that Ghana so desperately needs.

USAID mission offices have specific strategic priorities and associated operational plans, which dictate the makeup of the staff employed at any given time. In this case, there was no one water specialist who could take on this important task. I had an M.S. in water management, so I was passed the baton. If the Water for the Poor Act is going to have a significant impact, USAID missions must have the technical capacity to assimilate the funds.

Dabelko and Salzburg’s discussion brought up even more questions for me: How can the United States reconcile its bilateral earmark funding for water with the growing trend toward donor coordination—for instance, under the 2005 Paris Declaration, or, in the case of Ghana, the Multi-Donor Budget Support fund, which encourages donors to contribute direct financial support to the Ghanaian government to implement its Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy? Is there a need to have water specialists assigned to USAID missions, rather than relying on specialists in Washington, D.C.? How can we make municipal financing mechanisms for infrastructure more attractive to Western funders and host-country governments? Although Dabelko and Salzburg might not have had all the answers to these questions, I’m heartened that they and other water experts are tackling the tough issues.

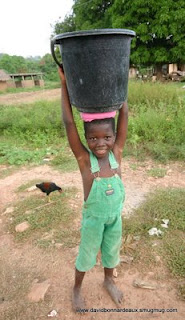

David Bonnardeaux is a freelance consultant on rural development and natural resource management for the World Bank, USAID, and CARE, among others. He is also an amateur photographer (www.davidbonnardeaux.smugmug.com). His next port of call is Vietnam.

Photos: Top: Boy pumping water, Volta Region, Ghana. Bottom: Girl collecting water from lake, Volta Region, Ghana. Courtesy of David Bonnardeaux. -

At the Fifth World Water Forum, Africa Steps Up

› A record-breaking 28,000 people, including five heads of state, participated in the Fifth World Water Forum in Istanbul, Turkey, last month. I was there, too, excited to be discussing this year’s theme, “Bridging Divides for Water.” Much of the conversation centered on how to bridge the remaining divides in meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)—especially MDG 7, which aims to halve the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015.

A record-breaking 28,000 people, including five heads of state, participated in the Fifth World Water Forum in Istanbul, Turkey, last month. I was there, too, excited to be discussing this year’s theme, “Bridging Divides for Water.” Much of the conversation centered on how to bridge the remaining divides in meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)—especially MDG 7, which aims to halve the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015.

While notable progress has been made in many regions of the world, such as China and India, other areas, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, lag woefully behind. According to the most recent numbers (2006) by UNICEF and the World Health Organization, only 31 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa has access to sanitation, and there are 38 sub-Saharan African countries where sanitation coverage is less than 50 percent. Access to improved drinking water sources has increased to 64 percent across the region; however, increases in coverage are not keeping pace with population growth, and the current rate of provision is not adequate to meet the MDG drinking-water target.

The Fifth World Water Forum, however, marked a hopeful new development. For the first time, the region of the world with the most serious water challenges, Africa, used the Forum to announce an internally driven water and sanitation agenda with a united voice. With support from the African Development Bank, the African Union and the African Ministerial Conference on Water (AMCOW) unveiled a plan to implement existing political commitments to water and sanitation. An “Africa Regional Paper” informed by the First African Water Week, held in Tunis in March 2008, presents African perspectives on each of the themes of the Forum (global change and risk management; advancing human development and the MDGs; managing and protecting water resources; governance and management; finance; education, knowledge, and capacity development), with a key message of delivering on existing commitments. In response to this agenda, the G8 countries announced increased aid to Africa’s water sector.

The desire to solve the world’s water crisis has generated many reports and frameworks over the years, including the Brundtland Commission’s report “Our Common Future” and the World Water Forum process itself. But perhaps nothing is as effective as a proactive, united stance from sub-Saharan Africans themselves, which could go a long way toward ensuring aid is used appropriately and efficiently. The fact that South Africa will host the Sixth World Water Forum in March 2012 should provide another impetus for meeting water and sanitation targets on the continent.

Hope Herron is an environmental scientist with Tetra Tech, Inc. She is currently researching water security issues in the context of the new U.S. Africa Command and U.S. defense, diplomacy, and development frameworks.

Photo: A Sudanese girl fills a water jug at a pump. Courtesy of Flickr user Water for Sudan. -

Teaching Geographic Perspectives on Environmental Security

› The intersection of the environment, security, and policymaking is often glossed over, even at a venerable institution like the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which trains the future officers of the U.S. Army. I am teaching a new mini-course within the geography program that aims to change this situation, using a region-specific approach. The course is designed to show geography majors how the environment can act as a catalyst for conflict or simply as an amplifier of existing problems. A series of 14 lessons will focus on defining environmental security, the role it plays in policymaking decisions, the significance of the military in these situations, and the intelligence-gathering and dissemination processes.

The intersection of the environment, security, and policymaking is often glossed over, even at a venerable institution like the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which trains the future officers of the U.S. Army. I am teaching a new mini-course within the geography program that aims to change this situation, using a region-specific approach. The course is designed to show geography majors how the environment can act as a catalyst for conflict or simply as an amplifier of existing problems. A series of 14 lessons will focus on defining environmental security, the role it plays in policymaking decisions, the significance of the military in these situations, and the intelligence-gathering and dissemination processes.

The military is evolving, and the armed services often find themselves involved in activities clearly classified as “other than war”; a key example is the recent formation of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), which focuses on “war prevention rather than war-fighting.” The bottom-line goal of West Point’s environmental security course is to educate future Army leaders on the interrelatedness of the environment and human activities, because these are issues they are likely to face in their careers.

The 11 students taking the course this semester will be required to read, comment on, and analyze a New Security Beat blog topic they find especially interesting, as well as pitch an idea for a potential blog entry. The blogging project is being incorporated into the course to expose students to near real-time perspectives from subject-matter experts in environmental security and related fields. Other readings will come from peer-reviewed journals, the Army War College, and other U.S. government sources. The course will conclude with an integrative experience where students apply what they have learned to a set of “what-if” scenarios from across the globe.

The mini-course, along with the blog exercise, has been a welcome addition to the geography program’s line-up. Feedback from this first-ever attempt to teach environmental security to geography majors at West Point will be compiled, and environmental security will either be developed into a more comprehensive course or split among several existing courses within the geography curriculum, such as environmental geography, climatology, and several regional geography courses. I look forward to sharing my reflections on teaching the mini-course with New Security Beat readers in the coming months.

Photo: U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Courtesy Flickr user Devonaire Eye.

Lieutenant Colonel Luis A. Rios USAF is an assistant professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. -

Demography and “Aging Alarmists”

›In an op-ed published in The Washington Post on January 4, Neil Howe and Richard Jackson of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) sound the alarm about the “massive disruption” the world may face in the 2020s due to population aging. Howe and Jackson co-authored The Graying of the Great Powers (see New Security Beat review), a 2008 CSIS report that elaborates on the supposed “political warfare” that will break out as a result of aging in the developed world, accompanied by turmoil in developing countries with young populations.

As fertility in many developed countries has fallen below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per couple necessary to maintain a stable population, an “aging alarmist” perspective has gained increasing credence among policymakers and the media. Using ominous rhetoric (as in the title of Phillip Longman’s book The Empty Cradle: How Falling Birthrates Threaten World Prosperity And What To Do About It and the recent film “The Demographic Winter: The Decline of the Human Family”), aging alarmists have successfully inspired fears of economic collapse and even near-extinction of the populations of entire countries (Howe and Jackson highlight a magazine cover story entitled “The Last German”). At times, these arguments take an overtly xenophobic tack (as in Pat Buchanan’s 2002 book The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization).Demographic experts certainly agree with the basic argument that population aging will have significant economic and social consequences. Human societies have had little experience addressing aging populations, and governments have so far proven largely unsuccessful at spurring higher fertility levels. However, the claim that aging will create social and economic implosion across most of the developed world crosses the line into pure speculation. Population aging is not a shock or a catastrophe; it occurs over a period of decades, allowing governments to plan and develop appropriate policy responses. While some protests over reductions in entitlement benefits such as pensions are likely, the repercussions of aging may not be entirely negative. Older adults in developed countries, whose life expectancies have lengthened, may be economically productive into their sixties and beyond, rather than simply decimating national health care budgets. In addition, governments may adjust to aging by modifying their labor force and outsourcing work to the developing world, where the need for jobs is plentiful.

Although no one can predict the future, we can accurately describe the present. Yet alarmists often present a skewed picture of current population trends and minimize the world’s demographic divide. The world still gains 78 million people per year, and 57 percent of the world’s people live in countries with growing populations. More than 95 percent of population growth through mid-century is projected to occur in the developing world. The huge challenge of addressing developing-country population growth by providing sufficient educational and employment opportunities despite high poverty rates is likely to be much more difficult to resolve than the challenge of population aging faced by wealthy developed countries with a high degree of human capital.

Motivated by such complex factors as access to basic health services, the social status and education levels of women, and migration patterns, demographic trends are far from static. Many countries have witnessed dramatic progress through the demographic transition—the shift from high mortality and fertility rates to longer lives and smaller family size—and these countries are now generally the most peaceful, the most democratic, and the wealthiest on the planet. The sustained declines in fertility that these countries have experienced are largely due to the availability of voluntary, rights-based family planning and reproductive health care. The impact of these programs is visible in the lower fertility rates of countries as diverse as Mexico, Indonesia, Iran, the Philippines, and Tunisia. In contrast, countries with extremely young populations—including many in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa—face a significantly higher risk of civil conflict than countries with more balanced age structures. Senior intelligence officials such as CIA Director Michael Hayden have recently highlighted population’s key role in security and development.

Howe and Jackson conclude by citing Abraham Lincoln’s description of the United States as “the world’s last best hope”—in this case, because its relatively constant population may leave it as the only stable democracy while the rest of the world faces demography-induced mayhem. Although this vision may be overstated, U.S. leadership is indeed critical to moving global demographic trends in a positive direction. Even as the policy debate surrounding population aging continues, the United States must remain a staunch supporter of development assistance programs, including family planning and reproductive health, for countries on the other side of the demographic divide.Elizabeth Leahy is a research associate at Population Action International (PAI). She is the primary author of the 2007 PAI report The Shape of Things to Come: Why Age Structure Matters to a Safer, More Equitable World.

-

The Biological Roots of Conflict

› Armed conflict and its consequences concern us all. But where does war actually come from? In our new book, Sex and War: How Biology Explains War and Terrorism and Offers a Path to a Safer World, Thomas Hayden and I argue that warfare and terrorism are written in our DNA. But that doesn’t mean humanity is doomed to a future as violent as our past has been. Understanding the biological basis of our warring instincts, we argue, gives us our best hope of decreasing the frequency and brutality of warfare.

Armed conflict and its consequences concern us all. But where does war actually come from? In our new book, Sex and War: How Biology Explains War and Terrorism and Offers a Path to a Safer World, Thomas Hayden and I argue that warfare and terrorism are written in our DNA. But that doesn’t mean humanity is doomed to a future as violent as our past has been. Understanding the biological basis of our warring instincts, we argue, gives us our best hope of decreasing the frequency and brutality of warfare.

Biologically speaking, war is an unusual behavior—very few other animals intentionally set out to kill members of their own species. Along with chimpanzees, with which we share a common evolutionary ancestor, we humans have a rare and terrible behavioral predisposition: Our young males, in the prime of life, are prone to band together and attack members of neighboring groups. The conflicts currently underway in the the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Darfur, Iraq, and elsewhere all have many proximate causes—political, religious, environmental, and otherwise. But contrary to long-held beliefs about the cultural roots of war, we argue that the behavior that makes the systematic slaughter of other human beings possible in the first place is based on a suite of evolved behavioral predispositions, which we call “team aggression.”

Anyone who has been in combat will tell you he fought not for a flag, or democracy, or some other abstraction, but for his buddy in the trench, his mate in the torpedo boat, or the soldier next to him in the up-armored Humvee. Intense loyalty for one’s immediate comrades, along with loss of empathy for the members of the enemy, are at the heart of team aggression, and of warfare and terrorism. These predispositions stretch back more than seven million years to our ape ancestors’ early battles for survival. We are all descended, by definition, from the victors of innumerable conflicts over resources, territory, and the right to mate. And we bear the marks of this legacy in the behaviors and impulses that spur us on to lethal conflict to this day, even when other solutions might be available.

The big question then becomes not, “Why do wars break out?”—that is the easy part—but, “Why does peace break out?,” as we know it often does. Far from condemning us to a future of warfare, understanding war’s biological roots can point us toward policies that increase the likelihood of peace, which also has deep roots in our biology. The first step toward peace is to do everything possible to grant women greater decision-making power in society. Team aggression is primarily a male drive, and while women are certainly competitive and capable of fighting bravely and ferociously, in the vast expanse of human history there is not a single record of women banding together spontaneously to attack their neighbors. Our book argues that when women have more agency, their societies become less warlike.

Population size and growth rates are two more key factors in the quest for peace. Rapid population growth increases competition over resources, increases unemployment, and boosts the ratio of young to older men, and all of these factors help facilitate extremism and violence. Experience shows, however, that when women have the opportunity to control their own fertility, family size and population growth decline—demonstrating that accessible, voluntary family planning programs are powerful tools for peace.

There is an aphorism: “If you want peace, understand war.” In Sex and War, we argue that understanding war also means understanding our own biology and evolutionary history. If we can do that, we can find more ways to help the biology of peace win out over the biology of war.

Malcolm Potts is Bixby Professor of Population and Family Planning at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health. For more media coverage of Sex and War, see Newsweek, Wired Science, and The Scientist.

Showing posts from category Guest Contributor.

Every day it seems the headlines bring new worries about the future of Pakistan. But among the many challenges confronting the nation—including a

Every day it seems the headlines bring new worries about the future of Pakistan. But among the many challenges confronting the nation—including a  While it is now

While it is now

A record-breaking 28,000 people, including five heads of state, participated in the

A record-breaking 28,000 people, including five heads of state, participated in the  The intersection of the environment, security, and policymaking is often glossed over, even at a venerable institution like the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which trains the future officers of the U.S. Army. I am teaching a new mini-course within the geography program that aims to change this situation, using a region-specific approach. The course is designed to show geography majors how the environment can act as a catalyst for conflict or simply as an amplifier of existing problems. A series of 14 lessons will focus on defining environmental security, the role it plays in policymaking decisions, the significance of the military in these situations, and the intelligence-gathering and dissemination processes.

The intersection of the environment, security, and policymaking is often glossed over, even at a venerable institution like the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, which trains the future officers of the U.S. Army. I am teaching a new mini-course within the geography program that aims to change this situation, using a region-specific approach. The course is designed to show geography majors how the environment can act as a catalyst for conflict or simply as an amplifier of existing problems. A series of 14 lessons will focus on defining environmental security, the role it plays in policymaking decisions, the significance of the military in these situations, and the intelligence-gathering and dissemination processes. Armed conflict and its consequences concern us all. But where does war actually come from? In our new book,

Armed conflict and its consequences concern us all. But where does war actually come from? In our new book,