Showing posts from category *Main.

-

Geoff Dabelko On ‘The Diane Rehm Show’ Discussing Global Water Security

›April 13, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffECSP Director Geoff Dabelko was recently a guest on The Diane Rehm Show to discuss the just-released U.S. intelligence community assessment of world water security. He was joined by co-panelists retired Maj. Gen. Richard Engel (USAF) of the National Intelligence Council’s Environment and Natural Resources Program (a key figure in preparing the report), Jessica Troell of the International Water Program at the Environmental Law Institute, and Steve Fleischli of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The Department of State-requested assessment (outlined in more detail, here and here) is a very positive contribution, said Dabelko. It “moves away from the arm-waving, headline-grabbing, water wars frame – the kind of sky-is-falling frame that is intuitively appealing and certainly appealing for politicians and headline writers, but doesn’t really reflect the reality.” He continued:What this report instead does, is recognize that there’s been an awful lot of cooperation around water even in the face of scarcity and that that cooperation in part helps us avoid conflicts, whether they’re violent or political, and that we should invest in those institutions that help us get to cooperation.

Visit the show’s program page to listen to the full segment, or read the transcript here.

It also suggests that it’s inadequate and incorrect to think of water as just a single-sector issue. The report is quite clear in connecting it to energy, connecting it to food, connecting it to health, economic development, agriculture obviously, and so that recognition [in] analysis sounds in some way straightforward, but unfortunately, when we organize our responses, we often respond in sector, and there’s not nearly enough communication and cooperation.

And finally, the report does say that the future may not look like the past, and so while we don’t have evidence of states fighting one another over water – and the judgment of the report is in the next 10 years, we won’t see that – it does hold out the prospect for as we go farther down the line, in terms of higher levels of consumption and higher levels of population, that we need to pay special attention because there’s some particular river basins in parts of the world where, as I said, the future may not look like the past and we have greater concerns for higher levels of conflict.

Sources/Image Credit: The Diane Rehm Show. -

Invest in Women’s Health to Improve Sub-Saharan African Food Security, Says PRB

›“Future food needs depend on our investments in women and girls, and particularly their reproductive health,” says the Population Reference Bureau’s Jason Bremner in a short video on population growth and food security (above). Understanding why, where, and how quickly populations are growing, and responding to that growth with integrated programming that addresses needs across development sectors, are crucial steps towards a food secure future, he says.

Reducing Food Insecurity by Meeting Unmet Needs

In sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly one-fourth of the population lives with some degree of food insecurity, persistently high fertility rates help drive population growth, according to the policy brief that accompanies Bremner’s video.

On average, women in the region have 5.1 children, more than twice the global average total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.5. The United Nation’s medium-variant projections (which Bremner notes are often used to predict future food need) show the region more than doubling in size by 2050, but that projection rests on the assumption that the average TFR will drop to three by mid-century.

As many as two-thirds of sub-Saharan African women want to space or limit their births, but do not use modern contraception. While the reasons for not using modern contraception are many, ranging from cultural to logistical, the lack of funding for family planning and reproductive health services remains a serious impediment to improving contraceptive prevalence and, in turn, lowering fertility rates.

“Current levels of funding for family planning and reproductive health from donors and African governments fail to meet current needs, much less the future needs,” writes Bremner.

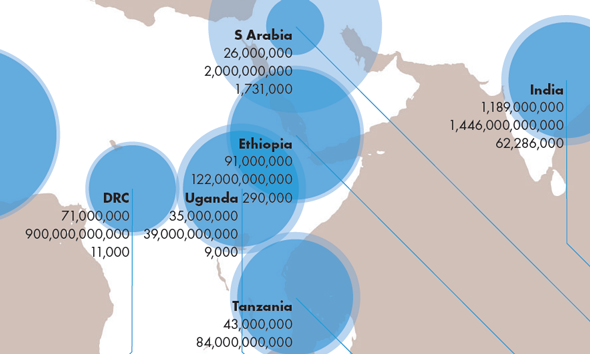

Almost 40 percent of the region’s population is younger than 15 years old and has “yet to enter their reproductive years,” writes Bremner. “Consequently, the reproductive choices of today’s young people will greatly influence future population size and food needs in the region.”Fertility Assumptions and Population Projections in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Family Planning Is One Piece of an Integrated Puzzle

Increasing funding for family planning services would be a boon to the region, but Bremner cautions that viewing sub-Saharan Africa’s rapid population growth solely from a health perspective and in isolation from other development needs would be inherently limiting.

“Slowing population growth through voluntary family planning programs demands stronger support from a variety of development sectors, including finance, agriculture, water, and the environment,” Bremner writes. A multi-sector approach that addresses population, health, livelihood, and environment challenges could mitigate future food insecurity more effectively than single-track programming that addresses sub-Saharan Africa’s various development needs in isolation from one another.

Improving women’s role in agriculture, for example, could help minimize food insecurity on a regional scale, Bremner writes. Women make up, on average, half the agricultural labor force in sub-Saharan Africa, and yet it is more difficult for them to own arable land, obtain loans, and afford basic essentials like fertilizer that can help boost agricultural productivity. Furthermore, women’s traditional household responsibilities, like fetching water, often cut into the amount of time they are able to give to farming. With those limitations lifted, women could offer enormous capacity for meeting future food needs.

Given the complex and interconnected nature of the development challenges facing sub-Saharan Africa, integrated cross-sector programming, with an emphasis on meeting family planning needs, is essential to reducing total fertility rates while improving food security over the long-term, according to Bremner.

“Investments in women’s agriculture, education, and health are critical to improving food security in sub-Saharan Africa,” he writes.

“Improving access to family planning is a critical piece of fulfilling future food needs,” he adds, “and food security and nutrition advocates must add their voices to support investments in women and girls and voluntary family planning as essential complements to agriculture and food policy solutions.”

Sources: Population Reference Bureau.

Video Credit: Population Reference Bureau. -

Responses to JPR Climate and Conflict Special Issue: John O’Loughlin, Andrew M. Linke, Frank Witmer (University of Colorado, Boulder)

›

Complexity, in terms of economic, cultural, institutional, and ecological characteristics, weighs heavily on contemporary attempts to unravel the climate change/variability and conflict nexus. The view that local-level complexity can be “controlled away” by technical fixes or adding variables in quantitative analysis does not sit well with many geographers (though some do try to adopt a middle ground position).

-

After the Disaster: Rebuilding Communities

›Recent history has shown that no country, developed or developing, is immune to the effects of a natural disaster. The catastrophic tsunami that struck Indonesia in 2004, the earthquake and subsequent tsunami that struck Japan in 2011, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and Hurricane Katrina in the United States in 2005, are all reminders of the deep and long-lasting impacts that disasters can have from the local neighborhood all the way up to the national level. Each of these disasters also garnered international attention and response, showing that globalization is a game-changer in the worldwide response to community or regional-level crises.

And yet, as evidenced by the continued challenges faced by each of the places above, the disaster response community still struggles with how to contribute most effectively to local level recovery. Recognizing this, the Wilson Center’s Comparative Urban Studies Project and Environmental Change and Security Program, and the Fetzer Institute recently brought together an international group of practitioners, policymakers, community leaders, and scholars to identify best practices and policy in disaster response that are based on community engagement. A subsequent publication, After the Disaster: Rebuilding Communities, highlights the complex nature of disaster response and explores ways to overcome the inherent tension between those responding to disasters and the local community.

Voice, Space, Safety, and Time

A key theme that emerged during the workshop was the importance of identifying the strengths of the post-disaster community and building responses based on those. So how can one identify the strengths of a community? In a previous Wilson Center/Fetzer Institute workshop on community resilience, participants emphasized the importance of civil society voice; the creation of space, both physical and political; and the assurance of safety and time.

Not surprisingly, all of these aspects of resilience emerged in the post-disaster response discussion as avenues to access the strengths of a community. Finding and listening to the voices of the community, identifying the physical spaces or “centers of gravity” around which the community operates (often spiritual and cultural activities, or gatherings that bring women together), and providing safe and sustained support for healing, are necessary steps to engage with and meet the needs of communities.

Having a voice means that people “feel that they have some way to participate meaningfully in decisions that are being made about their lives…[that] they have access, points of influence, and conversation,” explained John Paul Lederach, professor of international peacebuilding at the University of Notre Dame.

Key to listening to the voices of the local community is acknowledging them as first responders. “An involvement and control of the relief and rehabilitation process empowers communities,” wrote Arif Hasan, founder and chairperson of the Urban Resource Centre in Karachi, Pakistan. “It improves their relationship with each other, makes it more equitable with state organizations, and highlights aspects of injustice and deprivation that have been invisible.”

Technology is playing a growing role in giving local communities voice and helping relief workers to identify those centers of gravity. “Whether in conflict or even post-conflict reconstruction, technology gives us a possibility of having a collective history but also collective memory,” noted Philip Thigo, a program associate at Social Development Network in Nairobi. “I spoke in a conference where communities were able to map what was important for them and bring it to the public domain: This is who we are and what we are saying, therefore you, the government, have to interact with us within this space. In that sense technology begins to enable communities to say we exist.”

Connecting to Community Points of Power

At the same time, new technology isn’t paramount to connecting with a community, and just having the technology is not sufficient. Leonard Doyle, country spokesperson for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), shared the story of a simple but effective effort to encourage a national conversation in Haiti by enabling “a flow of information between affected communities, humanitarian actors, and local service providers.”

IOM set up more than 140 information booths, complete with suggestion boxes, among the 1,300 camps where more than 1.5 million homeless people were housed after the 2010 earthquake. There was some doubt that the suggestion boxes would attract letters in a country with just a 50 percent literacy rate, but it didn’t take long for the letterboxes to fill up. In just three days, 900 letters were dropped into a booth in one of the poorest communities, Cité Soleil.

“Amid the flotsam of emails and text messages that dominate modern life,” wrote Doyle, “these poignant letters had an authenticity that is hard to ignore….Urgent cases received a quick response; others became part of a ‘crowd-voicing’ effort to listen to those who had been displaced by the earthquake.”

In the end, “the problem is when we NGOs [or other outside bodies] try to create new systems,” observed Thigo. “We do not look at what exists in the community as knowledge. We do not see how to plug our formal thinking into a structure that we may not understand but that we could perhaps simply try to enhance, to provide better services. We think power doesn’t exist in those communities. But there’s a structure of power. It could be leadership that is not necessarily within the formal context that we understand. The fundamental point is: How can we, even during disasters, connect to these points of power?”

Download After the Disaster: Rebuilding Communities from the Wilson Center. -

Impressions of London’s Global Change Conference

›April 11, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe ECSP delegation to the 2012 Planet Under Pressure conference in London kept a keen eye on discussions of population and demographic dynamics during plenary and breakout sessions. And while the European frame of these topics resembles a much more open discussion of population pressures, presentations repeatedly looked at a broad suite of development challenges, avoiding the urge to elevate one challenge over another.

Out of the hundreds of panels during the week, we counted four that explicitly addressed population (one was hidden in the “Climate Compatible Development” program).

We polled a few participants on their take-aways from the conference, including Bishnu Upretti of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (above). Upretti’s focus is on South Asia, where water and food insecurity, poverty, population, and political tensions – all of which fit under the conference’s broad “global change” heading – are major issues. He came away with an overall positive impression, particularly in the conference’s potential as input for the upcoming Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development.

But some were not so optimistic about the overall global picture. “It’s all been a bit of a failure really,” said Chris Rapley of University College London on environmental change (below). “Humanity has proved itself incapable either of believing it, or even…getting a grip on the impact that it’s having on the planet.”

Though upbeat about progress in the natural sciences, Rapley argued that without better defining and communicating the consequences, threats, and risks at play, other political and economic concerns will continue to trump the climate and environment concerns.

“We can talk…in very general terms, but to both people and politicians and business people – all three parts of society that have to work together…really coherently to solve this problem – that sort of rather vague ‘gosh it looks a bit gloomy down there but we can’t tell you precisely what’s going to happen’ doesn’t cut the ice,” he lamented.

A Bridge Too Far?

At a conference like this, where topics are wildly diverse and overwhelming, distilling an easy narrative is difficult. Planet Under Pressure was a dizzying collection of natural scientists, inventors, students, journalists, professors, social scientists, and more. Collecting a group like this can shed light on dynamic and innovative work, not to mention foster collaboration on a tangible scale. However, finding grand solutions to the sheer number of challenges, or pressures, placed on the planet isn’t easy.

Yes, the planet is under pressure and this means the international community needs to talk about sustainability, climate change, and overall development in order to ensure a healthy planet for future generations, but nuanced discussion of difficult topics like population dynamics and human health are still a periphery part of the conversation.

The Planet Under Pressure Declaration – the collaborative statement intended to reflect the key messages emerging from the conference – leaves a lot to be desired in this regard. Sarah Fisher, a research and communications officer at the Population and Sustainability Network, suggested text for the declaration that included mention of population dynamics, including growth, urbanization, aging, and migration, in its framing of sustainable development, as well as explicit reference to the importance of human health and wellbeing.

But the final draft of the declaration was largely devoid of these issues, instead focusing more narrowly on environmental degradation and straightforward natural resource management.

For those looking to bridge the gap between the social and natural sciences, then, the focus shifts to the upcoming Rio+20 summit. The specter of the Earth Summit was tangible throughout the conference. From panels to informal discussions, the message was clear: there’s a lot more to be done.

For full population-related coverage from the conference, see our “Planet 2012 tag”. You can also join the conversation on Twitter (#Planet2012). Pictures from the event are available on our Facebook and Flickr pages – enjoy a few below.

Photo and Video Credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center.

Photo and Video Credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center.

-

Reproductive Health an Essential Part of Climate Compatible Development

›April 11, 2012 // By Sandeep BathalaECSP was at London’s 2012 Planet Under Pressure conference following all of the most pertinent population, health, and security events.

At a panel on “climate compatible development” at this year’s Planet Under Pressure global change conference, Population Action International’s Roger-Mark De Souza was the lone voice to speak about demographics. He presented a detailed analysis of population trends, based on collaboration with the Kenya-based African Institute for Development Policy.

“The link between population dynamics and sustainable development is strong and inseparable – as is the link between population dynamics, reproductive health, and gender equality,” said De Souza. These linkages were emphasized by the UN at the International Conference on Population and Development, held in Cairo in 1994, as well as during the original Rio Conference on Environment and Development in 1992.

“Climate compatible development” is a novel development paradigm being developed by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network and defined as “development that minimizes the harm caused by climate impacts, while maximizing the many human development opportunities presented by a low emissions more resilient future.”

The key tenet of this development framework is an emphasis on climate strategies that embrace development goals and integrate opportunities alongside the threats of a changing climate. In this respect, climate compatible development is seen as moving beyond the traditional separation of adaptation, mitigation, and development strategies. It challenges policymakers to consider “triple win” strategies that result in lower emissions, better resilience, and development – simultaneously.

Although developed nations are historically the major contributors of greenhouse gases due to comparatively high levels of consumption, developing countries are the most vulnerable to consequences of climate change. Emerging evidence shows that rapid population growth in developing countries exacerbates this vulnerability and undermines resilience to the effects of climate change, said De Souza. Socioeconomic improvement will also increase the levels of consumption and emissions from developing countries.

“Meeting women and their partners’ needs for family planning can yield the ‘triple win’ strategy envisaged in the climate development framework,” De Souza said. “Meeting unmet family planning needs would help build resilience and strengthen household and community resilience to climate change; slow the growth of greenhouse gases; and enhance development outcomes by improving and expanding health, schooling, and economic opportunities.”

Decision makers engaged in climate change policy planning and implementation at local, national, and international levels should have access to evidence on population trends and their implications on efforts to adapt to climate change as well as the overall development process, De Souza said.

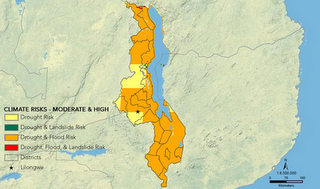

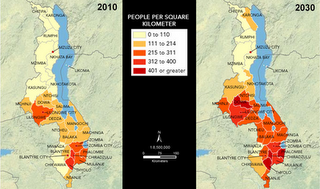

He presented new maps and analysis for Africa, particularly Malawi and Kenya, developed by PAI, building on earlier mapping work which identified 26 global population and climate change hotspots – countries that are experiencing rapid population growth, low resilience to climate change, and high projected declines in agricultural production.

“PAI’s work is a clear demonstration of how better decision making can be informed by the right analysis, in the right format, at the right time,” said Natasha Grist, head of research at the Climate Knowledge and Development Network.

“Most of the hotspot countries have high levels of fertility partly because of the inability of women and their partners to access and use contraception,” said De Souza. He continued:Investing in voluntary health programs that meet family planning needs could, therefore, slow population growth and reduce vulnerability to climate change impacts. This is especially important because women, especially those who live in poverty, are likely to be most affected by the negative effects of climate change and also bear the disproportionate burden of having unplanned children due to lack of contraception.

In conclusion, said De Souza, “global institutions and frameworks that support and promote climate compatible development can enhance the impact of their work by recognizing and incorporating population dynamics and reproductive health in their adaptation and development strategies.”

For full population-related coverage from the conference, see our “Planet 2012 tag.” Pictures from the event are available on our Facebook and Flickr pages, and you can join the conversation on Twitter (#Planet2012).

Sources: Climate and Development Knowledge Network, IPCC, Population Action International.

Photo Credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center; Maps: Population Action International. -

Peacemakers or Exclusion Zones? Saleem Ali on Transboundary Peace Parks

› “Traditionally, natural resources have been thought of as a source of conflict…but what we’ve been trying to do is look at the other side of the story, which is that natural resources, in terms of their quality, can create that impulse for conservation and cooperation,” said Saleem Ali, professor of environmental studies and director of the Institute for Environmental Diplomacy and Security at the University of Vermont, while speaking at the Wilson Center.

“Traditionally, natural resources have been thought of as a source of conflict…but what we’ve been trying to do is look at the other side of the story, which is that natural resources, in terms of their quality, can create that impulse for conservation and cooperation,” said Saleem Ali, professor of environmental studies and director of the Institute for Environmental Diplomacy and Security at the University of Vermont, while speaking at the Wilson Center.

This narrative around peace parks or transboundary conservation areas that are used for peacebuilding is a relatively recent field of research, said Ali. “It’s one thing to have a protected area on a border and have cooperation between friendly parties – like the U.S. and Canada,” he said, “and it’s a totally different thing to explore this in areas where there’s a history of protracted violent conflict.”

Yet, Ali said, we have “a good institutional framework for understanding what kind of parks could potentially be developed.” Cooperation between Ecuador and Peru in the Cordillera del Condor protected area, for example, is an incidence where transboundary conservation was actually written into the peace process between two warring states. Recent tragedies on the Siachen glaciers highlight another case where calls have been made to use peace parks as a way to demilitarize a contentious border over which India and Pakistan have long argued.

Questions remain though about the capacity of conservation processes to sustain peace, and “whether micro-conflicts that might arise through any conservation being practiced can be managed effectively.” Peace parks established in South Africa after apartheid, for example, produced “micro-conflicts between the haves and the have-nots – the classic conflict between conservation as an exclusionary arena versus a more inclusionary vision.”

“A lot of those organizations have learned from those past mistakes and we’re moving in the right direction,” Ali said, “but that’s still an area that requires far more research, and also more applied work, to find the right mix of conservation and economic development.” -

A New Land Security Agenda to Enable Sustainable, Equitable Development

›The recent news that overseas investors have acquired over 10 percent of Australia’s farmland and 9 percent of water entitlements in its agriculture sector has struck a political chord in the country. Large grain-producing nations like Brazil and Argentina have passed laws to restrict the foreign ownership of land. In other global grain hubs, like Ukraine and Russia, compromised harvests due to droughts could result in export restrictions. In a globalized economy, the combination of scarcity, market and population pressures, and weather volatility will make fertile land an increasingly precious resource.

A shift is underway in global financial markets, where global investors perceive that owning what grows on the land – or better still, owning the land itself – may be a hedge against the risks of more volatile financial markets. A surge in farmland investments is expected to grow over the next decade is due to a number of combined pressures: a growing global demand for commodities, rising commodity prices, ecological limits, and the fact that farmland is a “real asset” that offers diversification to the portfolios of investors at a time of market volatility.

The need to increase food production against the backdrop of resource limits, social vulnerability, and population growth, puts the question of land at the center of a new security agenda.

In sub-Saharan Africa large-scale acquisitions of land that neglect local livelihoods and resource scarcity, commonly referred to as “land grabs,” put the region’s future in the balance. Not all land investments have negative consequences, but given the lower levels of land tenure by communities and the fragility of human security in sub-Saharan Africa, regulating land investments with foresight is an urgent issue. Population growth and climate change underpin this agenda. A worse-than-average drought, exacerbated by climate change, may be all that is needed in certain places to realize the political, humanitarian, and ecological risks that are slowly building momentum.

From Land Grabs to Land Stewardship

Progress now depends on moving from a land grabs debate to land stewardship solutions. This shift, which the Earth Security Initiative summarized in a report published this month, The Land Security Agenda: How Investor Risks in Farmland Create Opportunities for Sustainability, requires an improved understanding by investors and political leaders of three priorities: managing land degradation, protecting human rights by focusing on food security and land ownership, and keeping economies within ecological – especially water – limits.

The agenda we have developed discusses why these issues form part of a new risk management agenda for investors as well as for countries seeking to attract foreign capital, whose economic competitiveness and political stability may be compromised by these trends. But managing these risks, we argue, will require making human rights and ecological limits a central feature of a new investment paradigm.

A range of international investors is already searching for solutions to engage practically with this debate. Among those with whom we have engaged throughout the study are individual investment funds, people seeking change within the financial sector, and investor networks such as the UN-backed Principles of Responsible Investment. Recently, governments, international organizations and civil society groups have also agreed on a set of voluntary guidelines for land governance under the auspices of the Committee on World Food Security. These developments are positive steps, but their voluntary nature remains problematic. The focus must now be placed on operationalizing their recommendations to ensure real accountability and creating political incentives in host countries to regulate their land to ensure long-term and equitable prosperity.

A Call to Action

In The Land Security Agenda we call on investors to turn their attention to their land and commodities portfolios, as well as the investments currently under due diligence, and begin to ask how soil resilience, the prosperity of local people, and freshwater limits are being considered. We recommend beginning to assess the risks of countries according to how well their governments are managing these issues.

We similarly call on heads of state in countries seeking to attract large investments in land to become more aware that these risks may undermine their country’s wealth, their stability, and economic competitiveness. Political leadership is needed to champion and enforce regulations that will encourage investments and modernization while protecting a country’s social and natural capital.

Some of the recommendations we have developed, which would help set the tone for investors and governments to move from voluntary principles to action, include:- Define land security parameters: Establish a set of verifiable measures that allows stakeholders to distinguish those land investments that advance equitable and sustainable prosperity from those that do not. Based on these criteria, which we suggest must consider people, water, and soil, it is possible to advance their integration into three important areas of the investment cycle: the identification of investment opportunities that build positive value, the due diligence process, and the performance reviews of fund managers.

- Build better country risk profiles: If the population of a given country is dependent on agriculture for livelihoods, shouldn’t issues like soil erosion, water availability and lack of recognition for people’s land rights increase that country’s sovereign risk? We think so and now seek to develop a “land security index” to help investors and host country governments assimilate these trends into their decisions as well as increase the advocacy capacity of local civil society.

- Advance the formal recognition of land rights on a large scale: The universal call for the prior and informed consent of communities must be supported, but will be of little practical value if communities do not hold the legal rights to their land or are not well informed about their rights and the commercial opportunities available to them. Civil society groups working to advance good governance, land titling, and capacity building – many of whom we have spoken to during this study – are in a position to help create a “land security partnership” that builds technical and political momentum for the formal recognition of land rights on a large scale, as well as the resourcing and oversight that government agencies will require to implement them.

Alejandro Litovsky is the founder and director of the Earth Security Initiative and lead author of the report. The Land Security Agenda can be downloaded here.

Sources: DGC Asset Management, Land Commodities Asset Management, Telegraph.

Image Credit: Cover of the The Land Security Agenda.