Showing posts from category Guest Contributor.

-

Climate-Security Linkages Lost in Translation

›A recent news story summarizing some interesting research by Halvard Buhaug carried the headline “Civil war in Africa has no link to climate change.” This is unfortunate because there’s nothing in Buhaug’s results, which were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, to support that conclusion.

In fact, the possibility that climate change might trigger conflict remains very real. Understanding why the headline writers got it wrong will help us better meet the growing demand for usable information about climate-conflict linkages.

First, the headline writer made a simple mistake by translating Buhaug’s modest model results — that under certain specifications climate variables were not statistically significant — into a much stronger causal conclusion: that climate is unrelated to conflict. A more responsible summary is that the historical relationship between climate and conflict depends on how the model is specified. But this is harder to squeeze into a headline — and much less likely to lure distracted online readers.

Buhaug tests 11 different models, but none of the 11 corresponds to what I would consider the emerging view on how climate shapes conflict. Using Miguel et al. (2004) as a reasonable representation of this view, and supported by other studies, there seems to be a strong likelihood that climatic shocks — due to their negative impacts on livelihoods — increase the likelihood that high-intensity civil wars will break out. None of Buhaug’s 11 models tested that view precisely.

If we are going to make progress as a community, we need to be specific about theoretically informed causal mechanisms. Our case studies and statistical tests should promote comparable results, around a discrete number of relevant mechanisms.

Second, a more profound confusion reflected in the headline concerns the term “climate change.” Buhaug’s research did not look at climate change at all, but rather historical climate variability. Variability of past climate is surely relevant to understanding the possible impacts of climate change, but there’s no way that, by itself, it can answer the question headline writers and policymakers want answered: Will climate change spark more conflict? For that we need to engage in a much richer combination of scenario analysis and model testing than we have done so far.

We are in a period in which climate change assessments have become highly politicized and climate politics are enormously contentious. The post-Copenhagen agenda for coming to grips with mitigation and adaptation remains primitive and unclear. Under these circumstances, we need to work extra hard to make sure that our research adds clarity and does not fan the flames of confusion. Buhaug’s paper is a good model in this regard, but the media coverage does not reflect its complexity. (Editor’s note: A few outlets – Nature, and TIME’s Ecocentric blog – did compare the clashing conclusions of Buhaug’s work and an earlier PNAS paper by Marshall Burke.)

The stakes are high. This isn’t a “normal” case of having trouble translating nuanced science into accessible news coverage. There is a gigantic disinformation machine with a well-funded cadre of “confusionistas” actively distorting and misrepresenting climate science. Scientists need to make it harder for them to succeed, not easier.

Here’s how I would characterize what we know and we are trying to learn:1) Economic deprivation almost certainly heightens the risk of internal war.

To understand how climate change might affect future conflict, we need to know much more. We need to understand how changing climate patterns interact with year-to-year variability to affect deprivation and shocks. We need to construct plausible socioeconomic scenarios of change to enable us to explore how the dynamics of climate, economics, demography, and politics will interact and unfold to shape conflict risk.

2) Economic shocks, as a form of deprivation, almost certainly heighten the risk of internal war.

3) Sharp declines in rainfall, compared to average, almost certainly generate economic shocks and deprivation.

4) Therefore, we are almost certain that sharp declines in rainfall raise the risk of internal war.

The same scenarios that generate future climate change also typically assume high levels of economic growth in Africa and other developing regions. If development is consistent with these projections, the risk of conflict will lessen over time as economies develop and democratic institutions spread.

To say something credible about climate change and conflict, we need to be able to articulate future pathways of economics and politics, because we know these will have a major impact on conflict in addition to climate change. Since we currently lack this ability, we must build it.Marc Levy is deputy director of the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), a research and data center of the Earth Institute of Columbia University.

Photo Credit: “KE139S11 World Bank” courtesy of flickr user World Bank Photo Collection.

-

New World Bank Report on Land Grabs Is a Dud

›After months of delays and false starts, and a tantalizing partial leak to the Financial Times earlier this summer, the much-ballyhooed World Bank report on large-scale land acquisitions has finally arrived.

-

Misguided Projections for Africa’s Fertility

›By assuming that sub-Saharan Africa’s total fertility rate will decrease to 2.5 children per woman by 2050, the most recent population projections issued by the Population Reference Bureau likely continue to underestimate fertility for Africa. Though northern Africa has significantly lowered fertility, sub-Saharan Africa’s TFR is still 5 children per woman. Achieving the levels projected by PRB or the United Nations will largely depend on whether the conditions that led to past fertility declines for other states can be established in sub-Saharan Africa.

Demographers have identified numerous factors associated with fertility decline, including increased education for females, shifting from a rural agricultural economy to an industrial one, and introduction of contraceptive technology. Sub-Saharan Africa is only making slow progress in each of these areas.

Surveying Obstacles to Development

Primary school enrollment is up, but the pace of improvement is declining. Meanwhile, gender gaps persist: Enrollment for boys remains significantly higher than for girls. Girls’ education is associated with lower fertility, partly because education helps women take charge of their fertility and also because education influences employment opportunities. Increased female labor force participation has been shown to increase the cost of having children, and is therefore associated with initial fertility declines.

Disease is one wildcard for Africa that limits the utility of past models of demographic transition in the African context. HIV/AIDS is decimating sub-Saharan Africa’s adult workforce and creating shortages of teachers that will impede future efforts to boost primary school enrollment. According to the United Nations, the number of teachers in sub-Saharan Africa needs to double in the next five years to reach Millennium Development goals.

Development that would shift the region’s economies from agriculture to industry is also lagging. While several West African countries are seeing some gains, the African continent on the whole faces major structural impediments to development. In The Bottom Billion, Paul Collier points out that many of these countries may have “missed the boat” to attract investment and industry that would pull the region out of poverty, partly because the least developed countries are still not cost-competitive enough when compared with current centers of manufacturing, like China.

Finally, there remains a high unmet need for family planning. One in four women aged 15 to 49 who are married or in union –- and who have expressed an interest in using contraceptives — still do not have access to family planning tools. In general, maternal mortality remains high and adolescents in the poorest households are three times more likely to become pregnant and give birth than those in the richest households, according to the most recent UN Millennium Development Goals report.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Off the Radar?

Sub-Saharan Africa suffers from a lack of attention by the international community and lack of political capacity at home. Many countries in the region are plagued by civil strife and poor governance, and developed countries continue to fall short of development assistance pledges. There is not the same sense of urgency today among developed countries about the global population explosion as there once was. Cold War politics and the environmental and feminist movements motivated much of the study of fertility and funding of population programs during the second half of the 20th century. Attention by governments and NGOs sped the fertility transition among many countries.

Today, the world’s wealthiest countries are not concerned primarily with Africa’s problems, but rather are more concerned with their own population decline and with the national security implications of population trends in areas associated with religious extremism. The recession has further hindered the flow of development funds.

Fertility is the most difficult population component to predict, and demographers must draw on the experiences of other regions to inform assessments of Africa’s population patterns. Demographers seem to be overconfident that Africa’s fertility will follow the pattern of recent declines, particularly in Latin America, which were more rapid than Western Europe’s decline due to the diffusion of technology and knowledge.

Once states begin the demographic transition towards lower fertility and mortality, they have tended to continue, with few exceptions. Therefore, most projections for Africa assume the same linear pattern of decline will hold. Yet, the low priority of Africa’s population issues among the world’s wealthiest states, combined with shortfalls in education, development, and contraception, may mean that the demographic transition in Africa will be slower than predicted.

Projections are useful to give us a picture of what the world could look like if meaningful policy changes are made. In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, prospects for these projections are dim.

Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba is the Mellon Environmental Fellow in the Department of International Studies at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tenn. She is also the author of a forthcoming book, The Future Faces of War: Population and National Security.

Photo Credit: “Waiting,” ECWA Evangel Hospital, Jos, Nigeria, courtesy of flickr user Mike Blyth. -

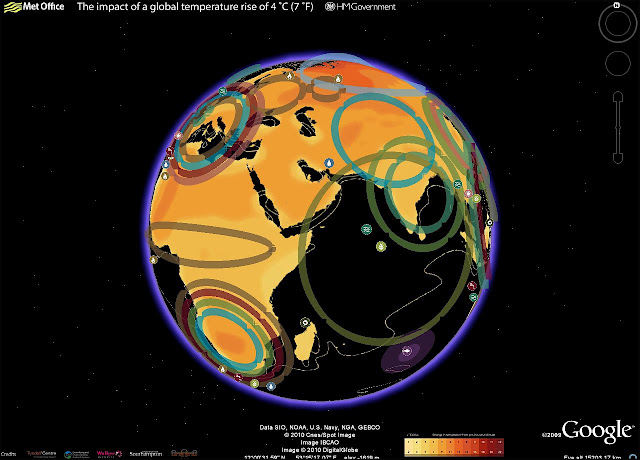

Rear Admiral Morisetti Launches the UK’s “4 Degree Map” on Google Earth

›Having had such success with the original “4 Degree Map” that the United Kingdom launched last October, my colleagues in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office have been working on a Google Earth version, which users can now download from the Foreign Office website.

This interactive map shows some of the possible impacts of a global temperature rise of 4 degrees Celsius (7° F). It underlines why the UK government and other countries believe we must keep global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial times; beyond that, the impacts will be increasingly disruptive to our global prosperity and security.

In my role as the UK’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy I have spoken to many colleagues in the international defense and security community about the threat climate change poses to our security. We need to understand how the impacts, as described in this map, will interact with other drivers of instability and global trends. Once we have this understanding we can then plan what needs to be done to mitigate the risks.

The map includes videos from the contributing scientists, who are led by the Met Office Hadley Centre. For example, if you click on the impact icon showing an increase in extreme weather events in the Gulf of Mexico region, up pops a video clip of the contributing scientist Dr Joanne Camp, talking about her research. It also includes examples of what the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and British Council are doing to increase people’s awareness of the risks climate change poses to our national security and prosperity, thus illustrating the FCO’s ongoing work on climate change and the low-carbon transition.

Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti is the United Kingdom’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy. -

Trillions of Dollars of Minerals? Misusing Geology and Economics to the Detriment of Policy

›Monday’s New York Times article, “U.S. Identifies Vast Mineral Riches in Afghanistan,” triggered a memory of a 70s-era Popular Science magazine cover that screamed “$3 trillion of minerals on the ocean floor!” That article, along with speeches from promoters of deep seabed mining, built up the anticipation that there were windfall profits to be had from the deep seabed. From this gross misuse of geologic speculation came all the difficulties with the negotiations of Part XI of the Law of the Sea Convention — and the United States’ continuing struggle to join the convention.

One of my roles on the U.S. delegation to the Law of the Sea Conference in 1979 and 1980 was to play defense against the misuse of geology and mineral economics in the negotiations, both by countries on the other side of the negotiating table and by seabed mining promoters at home. Part of that task was to gather and accurately “translate” the scientific and economic data from mineral statistics agencies, including the U.S. Bureau of Mines (since incorporated into the U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]), for policymakers and diplomats.

At times I felt like a goalie in the Part XI negotiations, blocking shots being taken by the forwards of the other teams that were promoting seabed mining as an economic bonanza. Unfortunately, by that time, too many groups had a vested interest in portraying the profitability of deep seabed mining and we couldn’t (yet) turn back the clock to a more reasonable approach.

When I read this week’s article in The New York Times, I had the same feeling of policy being manipulated by misuse of geologic data. With some help, I located the original DOD powerpoint presentation. The differences illustrate how science and economics can be misused to cause extensive damage in the policy process—a lesson I learned from the Law of the Sea negotiations.

The New York Times left out two important items from the DOD graphic accompanying the article:

First, the word “undiscovered” was left out; the original phrase reads “known and estimated ‘undiscovered’ resources anticipated by USGS and AGS and using prices as of 12/09.” Not only does that hide the important fact that the resources cited have not yet been discovered, it obscures that the estimates are largely defined by the USGS as either “hypothetical” and “speculative” resources — not the kind of numbers on which to stake a strategy for war and peace.

Second, the article omitted a caveat from DOD’s original powerpoint slide: “USGS agrees with the assertion: ‘At least 70 percent of Afghanistan’s mineral resources are yet to be identified.’”

Therefore, less than 30 percent of DOD’s estimated value is based on tangible evidence of deposits and 70 percent of the estimate is based on hypothetical or speculative resources of uncertain grade and abundance.

The value depends not just on metal content but also on the type of mineral, the grade (percent metal content) in the deposit, the size of the deposit, the distance from fuel and power, the amount of earth that covers the deposit, among other factors. If this report had geological merit as a USGS report, it would have said how much ore was in place at what grade.

Assigning a value to as yet undiscovered deposits is an effective way to influence a policymaker in a powerpoint presentation or generate a headline story from a reporter who has no experience with the terms of art used by geologists. But it has little to do with reality.

So, I drafted these points in response to the story in The New York Times:- According to the USGS, at least 70 percent of Afghanistan’s mineral wealth as estimated by the DOD is hypothetical or speculative, based on geologic theories, not measurement.

- The value estimates are grossly exaggerated by including sub-economic resources because they fail to consider capital and operating costs of recovery and processing to recover ore and convert it to finished metal.

- The DOD assessment fails to note whether the known or hypothetical deposits in Afghanistan are capable of competing economically with known and hypothetical deposits elsewhere in the world.

- Seventy-six percent of the estimated value comes from iron and copper, both of which are already found and produced in many locations around the world in commercially viable mines.

- The DOD values fail to distinguish between economically viable deposits and those that cannot be profitable in the foreseeable future, or to note those that are entirely speculative.

- The headline value of nearly $1 trillion is grossly in error and misinforms policymakers as to the economic potential of mineral deposits in Afghanistan.

Caitlyn L. Antrim is the executive director of the Rule of Law Committee for the Oceans. This article originally appeared in The Ocean Law Daily. To subscribe, please email caitlyn@oceanlaw.org.

Read more on Afghanistan’s mineral wealth and transparency initiatives on The New Security Beat.

Photo Credit: “Sunrise in Afghanistan,” courtesy of flickr user The U.S. Army. -

The Contradictions That Define China

›As a China follower who has visited the country numerous times over the past 40 years, I have an enduring love affair with the “old” China, which prided itself on balancing the harmony of nature with its decision-making. It is tragically ironic that despite this impressive historical and cultural backdrop, current choices have pushed the country’s harmony with nature beyond the tipping point.

The atmosphere in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province in central China, tells a cautionary tale of China’s current emphasis on economic growth at the expense of its citizens’ health. With lower annual sunshine totals than London, Chengdu’s perpetually grey, cloudy horizon graphically illustrates the massive industrial waste and coal-fired pollution that plague this booming city.

In April, global health experts convened in Chengdu at the 5th International Academic Conference on Environmental and Occupational Medicine, which was co-sponsored by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Chinese CDC offices, to report on the impact of climate change on public health.

Because of its geography, the mountain-encircled basin in which Chengdu sits is the natural point of release for daily deposits of air pollutants and dust blown in from India and other countries to the west. A rapid series of satellite views presented by John Petterson, director of the Sequoia Foundation, brought gasps from conference attendees, as these accumulated industrial wastes were shown concentrating against the massive southern Tibetan mountain range, then turning grey and black as they moved east, before being deposited on Sichuan’s vulnerable (and already heavily polluted) basin.

Environmental risk factors, especially air and water pollution, are a major–and worsening–source of death and illness in China. Air quality in China’s cities is among the worst in the world, and industrial water pollution is a widespread health hazard.

And although air pollution is clearly a complex global problem, individual nation-states continue to approach this dilemma as though it lies between its borders alone.

Luckily, this conference was prefaced by a number of timely scientific articles on China in the Lancet. The predominantly Chinese authors clearly take the critical risks that we expect from the Lancet, which is a defender of accountability and transparency in global health. This issue brings shame to other publications who still consider their “place” to be protecting the conventional politico-economic emphasis on decision-making inherent to most industrialized countries.

At the conference, public health and climate experts openly voiced their frustration at the blatant privileging of economic priorities over the health of unknowing populations. China–the fastest growing economy in world history, with unprecedented growth driven by external “demand” and precipitous acceleration of domestic consumption–has become the poster-child for global ignorance. However, the West is an equal and essential partner, having moved their manufacturing to China for cheap labor, lax environmental regulations, and higher profits.

Dr. Mark Keim, senior advisor for the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health, presented irrefutable evidence that root structure erosion from advancing saltwater has led to starvation in Polynesia, the first recorded evidence-based outcome measure of climate change’s public health effects.

At Mark’s request, I presented evidence on the worsening health impacts of rapid urbanization, specifically within urban enclaves that expand due to dense population growth before protective public health infrastructures and systems are in place (forthcoming in Prehospital and Disaster Medicine). Currently, the megacities in Asia and Africa–where sanitation is ignored and infectious disease is prevalent–now have the highest infant and under-age five mortality rates in the world.

Today, we face the largest gap in health indices between the haves and have-nots since the alarming days before the Alma-Ata Declaration. This new health data was an uncomfortable surprise to many conference attendees, most of whom were experts in the physical and environmental sciences.

We have become too “vertical” in our research over the past 50 years, and thus we fail to recognize that solutions to problems facing the global community must be trans-disciplinary and multi-sectoral, and serve multiple ministries and decision-makers.

If not undone by human decisions, global climate change and climate-warming greenhouse gases will rapidly intensify. This effort requires the best collaboration between science and the humanities, as well as the harmonious lessons of the “old” China.

Frederick M. Burkle, Jr., MD, MPH, DTM, is a senior public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and a senior fellow of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Photo Credit: Chengdu skyline in smog, courtesy Flickr user lonely radio. -

Look Beyond Islamabad To Solve Pakistan’s “Other” Threats

›After years of largely being ignored in Washington policy debates, Pakistan’s “other” threats – energy and water shortages, dismal education and healthcare systems, and rampant food insecurity – have finally moved to the front burner.

For several years, the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Asia Program has sought to bring these problems to the attention of the international donor community. Washington’s new determination to engage with Pakistan on its development challenges – as evidenced by President Obama’s signing of the Kerry-Lugar bill and USAID administrator Raj Shah’s comments on aid to Pakistan – are welcome, but long overdue.

The crux of the current debate on aid to Pakistan is how to maximize its effectiveness – that is, how to ensure that the aid gets to its intended recipients and is used for its intended purposes. Washington will not soon forget former Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf’s admission last year that $10 billion in American aid provided to fight the Taliban and al-Qaeda was instead diverted to strengthen Pakistani defenses against archrival India.

What Pakistani institutions will Washington use to channel its aid monies? In recent months, the U.S. government has considered both Pakistani NGOs and government agencies. It is now clear that Washington prefers to work with the latter, concluding that public institutions in Pakistan are better equipped to manage large infusions of capital and are more sustainable than those in civil society.

This conclusion is flawed. Simply putting all its aid eggs in the Pakistani government basket will not improve U.S. aid delivery to Pakistan, as Islamabad is seriously governance-challenged.

Granted, Islamabad is not hopelessly corrupt. It was not in the bottom 20 percent of Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index (Pakistan ranked 139 out of 180), and enjoyed the highest ranking of any South Asian country in the World Bank’s 2010 Doing Business report.

At the same time, the Pakistani state repeatedly fails to provide basic services to its population – not just in the tribal areas, but also in cities like Karachi, where 30,000 people die each year from consuming unsafe water.

Where basic services are provided, Islamabad favors wealthy, landed, and politically connected interests over those of the most needy – the very people with the most desperate need for international aid. Last year, government authorities established a computerized lottery that was supposed to award thousands of free tractors to randomly selected small farmers across Pakistan. However, among the “winners” were large landowners – including family members of a Pakistani parliamentarian.

Working through Islamabad on aid provision is essential. However, the United States also needs to diversify its aid partners in Pakistan.

For starters, Washington should look within civil society. This rich and vibrant sector is greatly underappreciated in Washington. The Hisaar Foundation, for example, is one of the only organizations in Pakistan focusing on water, food, and livelihood security.

The country’s Islamic charities also play a crucial role. Much of the aid rendered to health facilities and schools in Pakistan comes from Muslim welfare associations. Perhaps the most well-known such charity in Pakistan – the Edhi Foundation – receives tens of millions of dollars each year in unsolicited funds.

Washington should also be targeting venture capital groups. The Acumen Fund is a nonprofit venture fund that seeks to create markets for essential goods and services where they do not exist. The fund has launched an initiative with a Pakistani nonprofit organization to bring water-conserving drip irrigation to 20,000-30,000 Pakistani small farmers in the parched province of Sindh.

Such collaborative investment is a far cry from the opaque, exploitative foreign private investment cropping up in Pakistan these days – particularly in the context of agricultural financing – and deserves a closer look.

With all the talk in Washington about developing a strategic dialogue with Islamabad and ensuring the latter plays a central part in U.S. aid provision to Pakistan, it is easy to forget that Pakistan’s 175 million people have much to offer as well. These ample human resources – and their institutions in civil society – should be embraced and be better integrated into international aid programs.

While Pakistan’s rapidly growing population may be impoverished, it is also tremendously youthful. If the masses can be properly educated and successfully integrated into the labor force, Pakistan could experience a “demographic dividend,” allowing it to defuse what many describe as the country’s population time bomb.

A demographic dividend in Pakistan, the subject of an upcoming Wilson Center conference, has the potential to reduce all of Pakistan’s threats – and to enable the country to move away from its deep, but very necessary, dependence on international aid.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Photo Credit: Water pipes feeding into trash infected waterway in Karachi, courtesy Flickr user NB77. -

High Altitude Turbulence: Challenges to the Cordillera del Cóndor of Peru

›In 1998, Peru and Ecuador settled a long-running border dispute in the Cordillera del Cóndor mountain range that had killed and wounded dozens on both sides in 1995. In addition to pledging renewed cooperation on deciding the final placement of the border, the agreement, the Acta Presidencial de Brasilia, committed both sides to establishing extensive ecological protection reserves on both sides of the border: A peace park of sorts was born.

But now, indigenous groups fear that extractive industries in the area could threaten both the biodiversity and the ecological integrity of the forests and streams that they rely upon for their survival. They detail these charges in a new report, Peru: A Chronicle of Deception, and in a new video documentary, “Amazonia for Sale.”

Located on the eastern slopes of the Equatorial Andes, the area is a recognized global biodiversity hotspot with large areas of pristine montane habitat. In 1993-4, Conservation International led a biodiversity assessment trip to the area and identified dozens of species new to science. Their report, The Cordillera del Cóndor Region of Ecuador and Peru: A Biological Assessment, noted the “spectacular” biodiversity of the area, and its key role in the hydrological cycle linking the Andes with the Amazon.

Recognizing the region’s importance, the Acta Presidencial de Brasilia stipulated the need to create and update mechanisms to “lead to economic and social development and strengthen the cultural identity of native populations, as well as aid the conservation of biological biodiversity and the sustainable use of the ecosystems of the common border,” wrote Martin Alcade et al. in the ECSP Report.

Indigenous communities in Peru are accusing the Peruvian government of reneging on those promises by allowing extractive industries extensive access to the region. They charge that the government gave in to gold mining interests who want to reduce the size of the protected area in the Cordillera del Cóndor. They also claim that the Peruvian government is violating promises made to include indigenous peoples in the governance and management of the area.

Carefully managing extractive activities was a key priority for Peru and Ecuador when they negotiated an end to their border dispute. A management plan for the area with strong protection for key biodiversity areas was supposed to ensure everyone’s interests.

However, Peru’s current president, Alan Garcia, has been aggressive in promoting extractive industries in Peru,to the point of inciting significant popular opposition among many indigenous peoples. Less than a year ago, protests over oil exploration in Amazonian lowlands city of Bagua killed and wounded dozens of Peruvians. This violence followed years of social conflict over mining development in a number of communities in Peru’s Andean highlands.

Earlier this decade, Peru made some progress in resolving extractive disputes. But Garcia’s strong promotion of the extractive sector in the face of indigenous opposition, like we currently see in the Cordillera del Cóndor region, suggests years of confrontations to come.

Tom Deligiannis is adjunct faculty member at the UN-mandated University for Peace in Costa Rica, and an associate fellow of the Institute for Environmental Security in The Hague.

Photo Credit: “El vuelo del condor, acechando a su presa,” courtesy of flickr user Martintoy.