Showing posts from category food security.

-

Book Review: ‘Climate Conflict: How Global Warming Threatens Security and What to Do About It’ by Jeffrey Mazo

›June 8, 2010 // By Dan Asin The heated back-and-forth over climate conflict in the blogosphere and popular press prompts the questions: In the debate over the security threat of a warming planet, who is spewing the hot air? Does climate change precipitate conflict, and if so, who is most at risk?

The heated back-and-forth over climate conflict in the blogosphere and popular press prompts the questions: In the debate over the security threat of a warming planet, who is spewing the hot air? Does climate change precipitate conflict, and if so, who is most at risk?

In Climate Conflict: How Global Warming Threatens Security and What to Do About It, Jeffrey Mazo unabashedly argues that weak–but not yet failed–states are at the greatest risk of climate-driven conflict. Packed into only 166 pages, the book takes readers on a crash course through climate science; 10,000 years of human-environmental history; case studies of the pre-modern South Pacific and modern-day Colombia, Indonesia, and Darfur; and analysis of geopolitical instability and stressors. This tour d’horizon all builds up to one point: Global warming and climate change threaten our security.

Key to Mazo’s work is the important but oft-overlooked insight that it is not the magnitude of climate change, but the difference between the rate of climate change and a society’s ability to adapt that threatens stability. He also confronts the all-too-common assertion that accepting climate change as a threat multiplier absolves individuals of culpability, and is explicit that intrastate–rather than interstate–conflict is the norm.

The Weakest Are Not the Greatest Threat

Mazo weaves threads of non-traditional and human security throughout the text, asserting that “there is no real contradiction between humanitarian and security goals” (pg. 132). However, his primary concern is the security of the nation-state and the international system. He argues that the next two to four decades are the most relevant time for strategic planning.

Within this context, Mazo claims global warming’s central security challenge will be the threat it poses to stability in states that are either unable or unwilling to adapt. Few will be surprised, therefore, when he says weak, fragile, and failing states appear the most vulnerable.

Mazo suggests that already fragile or failed states lying in climate-sensitive areas–namely a handful of states in sub-Saharan Africa, plus Haiti, Iraq, and Afghanistan–are the most likely to experience increased volatility as a result of warming-induced climate change. Yet he departs from received wisdom when he suggests that global warming’s greatest threat to international security is actually how it will impact more resilient states like Burkina Faso, Colombia, and Indonesia.

Precisely because they are less at risk, the onset of instability in these states would have a greater impact. Exacerbating conflict or instability in a fragile or failed state, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, would not ripple through the international security framework in dramatically new ways. But the results of new conflict or instability in relatively stable states, such as Colombia, would. Mazo believes that the greater quantitative and qualitative impact of conflict in more resilient states renders them greater areas of concern.

Climate Factor Is One of Many

In no instance will climate change be the sole factor in conflict or state collapse. In already fragile or failed states, such as Sudan, instability is the product of a complex range of factors–political, social, and economic–many of which are non-environmental. “No single factor is necessary or sufficient,” writes Mazo (p. 126).

As it becomes increasingly pronounced, climate change may play a larger role in contributing toward volatility and instability. It is unlikely, however, to precipitate conflict where other risk factors do not already exist.

Adaptation Is Key

To address the threat to otherwise stable countries, Mazo advocates improving their latent capacity for adaptation. Good governance, rule of law, education, economic development: each is a key factor in a state’s ability to adapt. Variations across these factors may explain why death tolls from natural disasters in Bangladesh have fallen in recent years while those in Burma have risen.

Adaptation efforts should prioritize weak or recovering states that “have proved able to cope but are at particular risk,” Mazo writes (p. 133). Failing or failed states are either too susceptible to other conflict factors or too far advanced along the path of instability for adaptation to be of use to forestalling threats to international security. His argument is not to consign those in the most dire circumstances to a perpetual state of misery but, from a security perspective, to focus constrained resources on states where they will have the greatest impact. In states with the capacity to effectively absorb inflows, adaptation can preempt conflict, not simply reduce it.

Mazo does not ignore mitigation, and recognizes that it works in tandem with adaptation: Mitigation “is the only way of avoiding the most dire consequences of global warming, which would exceed the capacity of individuals, nations or the international system to adapt,” he notes (p. 124). Nevertheless, he argues that mitigation strategies “take much longer to bear fruit,” and that a certain amount of warming in the short- to medium-term is inevitable (p. 133). Against this warming, resilient adaptation is our best defense.

Case in Point: Indonesia

One otherwise stable state whose stability is threatened by climate change is Indonesia. Having suffered political and social unrest following the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and sectarian violence following Timor Leste’s independence in 1999, Indonesia avoided both failure and collapse to emerge as a flawed but vibrant democracy and Southeast Asia’s largest economy.

Indonesia is now home to the largest Muslim population in the world and is a key to regional security, yet its success “is potentially threatened by climate change,” writes Mazo; “food insecurity will be the greatest risk” (pg. 116).

Annual mean temperatures in Indonesia rose by 0.3°C between 1990 and 2005, and are predicted to rise an additional 0.36-0.47°C by 2020. The rainy seasons will shorten, increasing the risk of either flooding or drought. El Nino weather patterns–which in 1997 damaged over 400,000 hectares of rice and coffee, cocoa, and rubber cash crops–are expected to become more extreme and frequent in the future.

Climate change will further widen the substantial wealth gap between Indonesia’s rich and poor and, when it has differential impacts in different regions, “could lead to a revival of separatism” (pg. 117). While Mazo says threats from climate change will not be enough to push Indonesia into instability by themselves, he warns that if other destabilizing factors begin to emerge, “the added stress of climate change could accelerate the trend” (pg. 117).

Short and Sweet

Unlike some popular commentators on climate and security, Mazo does not confound brevity with hyperbole. While its concise format best lends itself to policymakers, students, and curious readers who are short on time, Climate Conflict’s content and its compendium of more than 320 citations make it deserving of a spot on everyone’s bookshelf. -

New Security Challenges in Obama’s Grand Strategy

›June 4, 2010 // By Schuyler NullPresident Obama’s National Security Strategy (NSS), released last week, reinforces a commitment to the whole of government approach to defense, and highlights the diffuse challenges facing the United States, including international terrorism, globalization, and economic upheaval.

Following the lead of the Quadrennial Defense Review released earlier this year, the NSS for the first time since the Clinton years prominently features non-traditional security concerns such as climate change, population growth, food security, and resource management:Climate change and pandemic disease threaten the security of regions and the health and safety of the American people. Failing states breed conflict and endanger regional and global security… The convergence of wealth and living standards among developed and emerging economies holds out the promise of more balanced global growth, but dramatic inequality persists within and among nations. Profound cultural and demographic tensions, rising demand for resources, and rapid urbanization could reshape single countries and entire regions.

By acknowledging the myriad causes of instability along with more “hard” security issues such as insurgency and nuclear weapons, Obama’s national security strategy takes into account the “soft” problems facing critical yet troubled states – such as Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and Somalia – which include demographic imbalances, food insecurity, and environmental degradation.

Not surprisingly, Afghanistan in particular is highlighted as an area where soft power could strengthen American security interests. According to the strategy, agricultural development and a commitment to women’s rights “can make an immediate and enduring impact in the lives of the Afghan people” and will help lead to a “strong, stable, and prosperous Afghanistan.”

The unique demographic landscape of the Middle East, which outside of Africa has the fastest growing populations in the world, is also given intentional consideration. “We have a strategic interest in ensuring that the social and economic needs and political rights of people in this region, who represent one of the world’s youngest populations, are met,” the strategy states.

Some critics of that strategy warn that the term “national security” may grow to encompass so much it becomes meaningless. But others argue the administration’s thinking is simply a more nuanced approach that acknowledges the complexity of today’s security challenges.

In a speech on the strategy, Secretary of State Clinton said that one of the administration’s goals was “to begin to make the case that defense, diplomacy, and development were not separate entities either in substance or process, but that indeed they had to be viewed as part of an integrated whole and that the whole of government then had to be enlisted in their pursuit.”

Compare this approach to President Bush’s 2006 National Security Strategy, which began with the simple statement, “America is at war” and focused very directly on terrorism, democracy building, and unilateralism.

Other comparisons are also instructive. The Bush NSS mentions “food” only once (in connection with the administration’s “Initiative to End Hunger in Africa”) and does not mention population, demography, agriculture, or climate change at all. In contrast, the 2010 NSS mentions food nine times, population and demography eight times, agriculture three times, and climate change 23 times – even more than “intelligence,” which is mentioned only 18 times.

For demographers, development specialists, and environmental conflict specialists, the inclusion of “new security” challenges in the National Security Strategy, which had been largely ignored during the Bush era, is a boon – an encouraging sign that soft power may return to prominence in American foreign policy.

The forthcoming first-ever Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review by the State Department will help flesh out the strategic framework laid out by the NSS. It is expected to provide more concrete policy for integrating defense, diplomacy, and development. Current on-the-ground examples like USDA embedding in Afghanistan, stepped-up development aid to Pakistan, and the roll-out of the administration’s food security initiative, “Feed the Future,” are encouraging signs that the NSS may already be more than just rhetoric.

Update: The Bush 91′ and 92’ NSS also included environmental considerations, in part due to the influence of then Director of Central Intelligence, Robert Gates.

Sources: Center for Global Development, CNAS, Los Angeles Times, State Department, USAID, White House, World Politics Review.

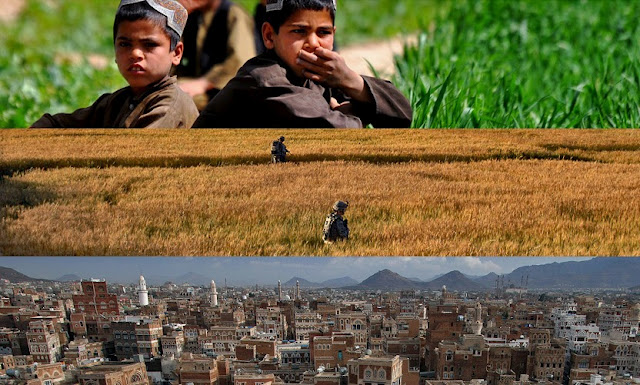

Photo Credit: “Human, Food, and Demographic Security” collage by Schuyler Null from “Children stop tending to the crop to watch the patrol” courtesy of flickr user isafmedia, “Combing Wheat” courtesy of flickr user AfghanistanMatters, and “Old Town Sanaa – Yemen 49” courtesy of flickr user Richard Messenger. -

Can Food Security Stop Terrorism?

›May 28, 2010 // By Schuyler NullUSAID’s “Feed the Future” initiative is being touted for its potential to help stabilize failing states and dampen simmering civil conflicts. Speaking at a packed symposium on food security hosted by the Chicago Council last week, USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah called food security “the foundation for peace and opportunity – and therefore a foundation for our own national security.”

-

USDA v. Taliban

›May 28, 2010 // By Dan AsinAgricultural development is the “top non-security priority” in Afghanistan, said U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, in a recent speech. “Unemployment is the best recruiting tool for the Taliban,” he told the Des Moines Register.

Sixty USDA experts are working with their partners in State, USAID, DOD, and other members of U.S. government to increase agricultural opportunities in rural areas of the country. Embedded in small civil-military units of 15-100 people, USDA experts have worked on projects of all scales: installing windmill water pumps, training veterinarians, refurbishing university research laboratories, stabilizing river banks and irrigation canals, and developing storage facilities.

In his keynote speech at the Feed the Future launch, Vilsack emphasized the need to build markets. In Afghanistan, USDA is focusing on improving infrastructure so farmers can receive deliveries and ship produce, and boosting credit vehicles to help farmers purchase the inputs to grow crops. Opium traders provide seeds to the farmers and pick up the crops at the farms, he said, which makes opium easier to produce than legal crops.

Alternative crops could be just as or more valuable, Vilsack told NPR:Table grapes are in some cases perhaps four and five times more valuable than poppy. Saffron, almonds, pomegranates, a number of fruits are significantly more profitable. What we have to do is we have to establish that the reward of putting those crops in the ground is greater and the risk is equal to or less than poppy production.

On the same NPR program, Vilsack’s counterpart agreed: “Agriculture growth means employment and employment means security. They’re so much related to each other. In places where the military operates, if you do not offer people the future, just by military means, security and stability will be a very far-reaching dream,” said Minister of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock Mohammad Asif Rahimi.

But the Afghan government faces an immense challenge: Afghanistan’s unemployment rate is estimated at 35 percent, which ranks it in the bottom 20 countries in the world. With a population growth rate of 3.5 percent and nearly half the population already under the age of 15, the need for job creation is only set to increase.

While agricultural development and food security are essential, Rahimi acknowledged, alone they are not enough. The Afghan government needs a “whole of government approach,” he said. To win the hearts of its people the government must offer “an alternative to what the Talibans were offering to people…more livelihood and security and education and health, and also a better and more secure future.”

Both Vilsack and Rahimi avoid the common trap of equating hunger with conflict, instead emphasizing agricultural employment and economic opportunities as key to solving that intractable conflict.

But it’s not the only piece of the puzzle. I hope the Feed the Future’s “whole of government” approach in Afghanistan will emphasize not only agriculture, but also the environmental policies and health services, such as family planning, that can ensure that agricultural gains are sustainable even after the troops leave.

Sources: Central Intelligence Agency, Des Moines Register, NPR, United Nations Statistics Division, United Nations Population Division, U.S. Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of State.

Photo Credit: Colonel Stephen Redman and John Van Horn of the USDA discuss crop plans with local residents while surveying the site of the Arkansas Agribusiness Development Team’s (ADT)demonstration farm plot near Shahr-e-Safa, Afghanistan, courtesy Flickr user isafmedia. -

Look Beyond Islamabad To Solve Pakistan’s “Other” Threats

›After years of largely being ignored in Washington policy debates, Pakistan’s “other” threats – energy and water shortages, dismal education and healthcare systems, and rampant food insecurity – have finally moved to the front burner.

For several years, the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Asia Program has sought to bring these problems to the attention of the international donor community. Washington’s new determination to engage with Pakistan on its development challenges – as evidenced by President Obama’s signing of the Kerry-Lugar bill and USAID administrator Raj Shah’s comments on aid to Pakistan – are welcome, but long overdue.

The crux of the current debate on aid to Pakistan is how to maximize its effectiveness – that is, how to ensure that the aid gets to its intended recipients and is used for its intended purposes. Washington will not soon forget former Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf’s admission last year that $10 billion in American aid provided to fight the Taliban and al-Qaeda was instead diverted to strengthen Pakistani defenses against archrival India.

What Pakistani institutions will Washington use to channel its aid monies? In recent months, the U.S. government has considered both Pakistani NGOs and government agencies. It is now clear that Washington prefers to work with the latter, concluding that public institutions in Pakistan are better equipped to manage large infusions of capital and are more sustainable than those in civil society.

This conclusion is flawed. Simply putting all its aid eggs in the Pakistani government basket will not improve U.S. aid delivery to Pakistan, as Islamabad is seriously governance-challenged.

Granted, Islamabad is not hopelessly corrupt. It was not in the bottom 20 percent of Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index (Pakistan ranked 139 out of 180), and enjoyed the highest ranking of any South Asian country in the World Bank’s 2010 Doing Business report.

At the same time, the Pakistani state repeatedly fails to provide basic services to its population – not just in the tribal areas, but also in cities like Karachi, where 30,000 people die each year from consuming unsafe water.

Where basic services are provided, Islamabad favors wealthy, landed, and politically connected interests over those of the most needy – the very people with the most desperate need for international aid. Last year, government authorities established a computerized lottery that was supposed to award thousands of free tractors to randomly selected small farmers across Pakistan. However, among the “winners” were large landowners – including family members of a Pakistani parliamentarian.

Working through Islamabad on aid provision is essential. However, the United States also needs to diversify its aid partners in Pakistan.

For starters, Washington should look within civil society. This rich and vibrant sector is greatly underappreciated in Washington. The Hisaar Foundation, for example, is one of the only organizations in Pakistan focusing on water, food, and livelihood security.

The country’s Islamic charities also play a crucial role. Much of the aid rendered to health facilities and schools in Pakistan comes from Muslim welfare associations. Perhaps the most well-known such charity in Pakistan – the Edhi Foundation – receives tens of millions of dollars each year in unsolicited funds.

Washington should also be targeting venture capital groups. The Acumen Fund is a nonprofit venture fund that seeks to create markets for essential goods and services where they do not exist. The fund has launched an initiative with a Pakistani nonprofit organization to bring water-conserving drip irrigation to 20,000-30,000 Pakistani small farmers in the parched province of Sindh.

Such collaborative investment is a far cry from the opaque, exploitative foreign private investment cropping up in Pakistan these days – particularly in the context of agricultural financing – and deserves a closer look.

With all the talk in Washington about developing a strategic dialogue with Islamabad and ensuring the latter plays a central part in U.S. aid provision to Pakistan, it is easy to forget that Pakistan’s 175 million people have much to offer as well. These ample human resources – and their institutions in civil society – should be embraced and be better integrated into international aid programs.

While Pakistan’s rapidly growing population may be impoverished, it is also tremendously youthful. If the masses can be properly educated and successfully integrated into the labor force, Pakistan could experience a “demographic dividend,” allowing it to defuse what many describe as the country’s population time bomb.

A demographic dividend in Pakistan, the subject of an upcoming Wilson Center conference, has the potential to reduce all of Pakistan’s threats – and to enable the country to move away from its deep, but very necessary, dependence on international aid.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Photo Credit: Water pipes feeding into trash infected waterway in Karachi, courtesy Flickr user NB77. -

Securing Food in Insecure Areas

›May 25, 2010 // By Dan Asin“Of the 1 billion people who are in food-stressed situations today, a significant proportion live in conflict-ridden countries,” said Raymond Gilpin of the U.S. Institute of Peace at last Thursday’s launch of USAID’s Feed the Future initiative. “Most of them live in fear for their lives, in uncertain environments, and without clear hope for a better tomorrow.”

According to data from the World Food Programme and the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Database, of the countries with moderately to very high hunger rates in 2009, nearly a quarter experienced violent conflict in the previous year, and nearly half in the preceding two decades.

Gilpin said those working toward food security need to develop “conflict-sensitive” approaches, because “a lot of fundamentals that underlie this problem have a lot to do with conflict.” He noted several points, from production to purchasing power, at which conflict enters to disrupt the farm to mouth food cycle:- Production: Be it forced or voluntary, internal or external, conflict often results in displacement. Farmers are not exempt, and when they’re not on their land they cannot produce.

- Delivery: “Food security isn’t always an issue of food availability; it’s an issue of accessibility,” he said. “When violent conflict affects a community or a region…it destroys infrastructure and weakens institutions.”

- Market access: In conflict zones, it is solitary or competing armed contingents, rather than the market’s invisible hand, that control access to supplies. “Groups who usually have the monopoly of force, control livelihoods and food and services,” he said.

- Purchasing power: Conflict disrupts economic activity, degrading both incomes and real wealth. Those remaining in the conflict area suffer from fewer opportunities to conduct business, while those choosing to migrate relinquish their assets. In instances where food is available to purchase, conflict reduces the number of individuals who can afford it.

Photo Credit: World Food Programme distribution site in Afghanistan, courtesy Flickr user USAID Afghanistan. -

21st Century Water

›The Economist published this week For Want of a Drink, its special report on water. The report, a compilation of 11 articles, is a mix of surveys of global management strategies, health impacts, and economic considerations on the one hand, and deeper looks into specific practices in Singapore, India, and China on the other. Most interesting for New Security Beat readers is the article “To the Last Drop: How to Avoid Water Wars.” The article states there have been “no true water wars,” but goes on to question whether the pressures of climate change and population growth could generate different outcomes in the future. While the challenges laid out are manifold, the article concludes that potential for cooperation is equally present. “The secret is to look for benefits and then try to share them. If that is done, water can bring competitors together.” Global Change: Impacts on Water and Food Security, published by IFPRI in collaboration with CGIAR and the Third World Centre for Water Management, is an anthology of focused articles studying “the interplay between globalization, water management, and food security.” While heavily focused on trade and finance, the articles span the spectrum of food and water challenges, from biofuels to the global fish trade. Overall, the book finds that “global change provides more opportunities than challenges,” but taking advantage of globalization’s opportunities demands “comprehensive water and food policy reforms.”

Global Change: Impacts on Water and Food Security, published by IFPRI in collaboration with CGIAR and the Third World Centre for Water Management, is an anthology of focused articles studying “the interplay between globalization, water management, and food security.” While heavily focused on trade and finance, the articles span the spectrum of food and water challenges, from biofuels to the global fish trade. Overall, the book finds that “global change provides more opportunities than challenges,” but taking advantage of globalization’s opportunities demands “comprehensive water and food policy reforms.” -

USAID’s Shah Focuses on Women, Innovation, Integration

›May 20, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffWomen in developing countries are “core to success and failure” of USAID’s plan to fight hunger and poverty, and “we will be focusing on women in everything we do,” said USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah at today’s launch of the “Feed the Future” guide.

But to solve the “tough problem” of how to best serve women farmers, USAID needs to “take risks and be more entrepreneurial,” said Shah, as it implements the Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative.

“A lot of this is going to fail and that’s OK,” Shah said, calling for a “culture of experimentation” at the agency. He welcomed input from the private sector, which was represented at the launch by Des Moines-based Pioneer Hi-Bred.

In one “huge change in our assistance model,” Feed the Future will be “country-led and country-owned,” said Shah, who asked NGOs and USAID implementing partners to “align that expertise behind country priorities” and redirect money away from Washington towards “building real local capacity.” USAID will “work in partnership, not patronage,” with its 20 target countries, he said.

To insure that the administration’s agricultural development efforts are aligned to the same goals, Shah said USAID will collect baseline data from the start on three metrics: women’s incomes, child malnutrition, and agricultural production.

“Whether it is finance, land tenure, public extension, or training efforts, it does not matter whether it is an ‘agricultural development’ category of program,” said Shah. All programs will “provide targeted services to women farmers.”

While Shah briefly mentioned integrating these efforts with the administration’s Global Health Initiative, he only gave one example. Nutrition programs would be tied to health “platforms that already exist at scale” in country, such as HIV, malaria, vaccination, and breastfeeding promotion programs, he said.

Targeting Food Security: The Wilson Center’s Africa Program Takes Aim

If “food supplies in Africa cannot be assured, then Africa’s future remains dismal, no matter how efforts of conflict resolution pan out or how sustained international humanitarian assistance becomes,” says Steve McDonald, director of the Wilson Center’s Africa Program, in the current issue of the Wilson Center’s newsletter, Centerpoint. “It sounds sophomoric, but food is essential to population health and happiness—its very survival—but also to productivity and creativity.”

The May 2010 edition of Centerpoint highlights regional integration, a key focus of U.S. policy, as a mechanism for assuring greater continuity and availability of food supplies. Drawing on proceedings from the Africa Program’s “Promoting Regional Integration and Food Security in Africa” event held in March, Centerpoint accentuates key conclusions on building infrastructure and facilitating trade.

Photo Credit: “USAID Administrator Shah visits a hospital in Haiti” courtesy Flickr user USAID_Images.