Showing posts from category environmental security.

-

Food and Environmental Insecurity a Factor in North Korean Shelling?

›November 24, 2010 // By Schuyler NullJust two days before dozens of North Korean artillery shells fell on the island of Yeonpyeong off the west coast of Korea, a UN study reported that the DPRK was facing acute food shortages heading into the winter.

In a New York Times report, Choi Jin-wook, of the Korea Institute for National Unification in Seoul, called food “the number one issue.” While Choi just last month praised the resumption of food aid from the South to the North as a “starting point of a new chapter in inter-Korean relations,” she told the Times Wednesday that the North is “in a desperate situation, and they want food immediately, not next year.”

North Korea’s motives are notoriously indecipherable and this latest incident is no exception, but the regime has in the past sought to distract from domestic problems by inciting the international community (the sinking of the Cheonan being the other latest prominent example).

Infrastructure has always been primitive in the North under the DPRK regime, but the country’s tenuous food security situation was made worse this last year by an unusually long and severe winter followed by heavy flooding in the summer. Flooding was so bad during August and September, that the normally silent regime publically announced details of rescue operations around the northern city of Sinuiju. The joint FAO/WFP report put out by the UN does not predicate production will significantly recover in the next year and estimates an uncovered food deficit of 542,000 tons for 2010/11.

“A small shock in the future could trigger a severe negative impact and will be difficult to contain if these chronic deficits are not effectively managed,” Joyce Luma of the World Food Program told The New York Times.

For more on the severe weather events of this summer, including the flooding that impacted the DPRK and pushed the Three Gorge Dam to its stress limits in China, the impact of scarcity and climate change on the potential for conflict, and the intersection of food security and conflict elsewhere, see our previous coverage on The New Security Beat.

Sources: Christian Science Monitor, Food and Agriculture Organization, Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, UN, Washington Post, World Food Program.

Image Credit: Google Maps. -

Nigeria’s Future Clouded by Oil, Climate Change, and Scarcity [Part Two, The Sahel]

›November 19, 2010 // By Schuyler NullIf southern Nigeria’s demographic and environmental problems have helped fuel today’s conflicts, it’s the north’s issues that may feed the conflicts of tomorrow.

Nigeria’s lack of development and poor governance is not exclusive to the delta region, only more well-known because its oil reserves. The north of the country, which is predominately Muslim and accounts for more than half of Nigeria’s population, faces many of the same problems of environmental degradation, lack of jobs, and inadequate infrastructure. Northern Nigeria is also growing much faster than the south, with a total fertility rate of 6.6 children per woman, compared to 4.6 in the southern states. The median age of first-time mothers in northern Nigeria is only 18 years old.Nigeria holds nearly a fifth of the entire population of sub-Saharan Africa. By 2050, it’s expected to pass Indonesia, Brazil, and Bangladesh and take its place among the top five most populous countries in the world, according to UN estimates. But a litany of outstanding and new development, security, and environmental issues – both in the long-troubled Niger delta in the south and the newly inflamed north – present a real threat to one West Africa’s most critical countries.

If southern Nigeria’s demographic and environmental problems have helped fuel today’s conflicts, it’s the north’s issues that may feed the conflicts of tomorrow.

Nigeria’s lack of development and poor governance is not exclusive to the delta region, only more well-known because its oil reserves. The north of the country, which is predominately Muslim and accounts for more than half of Nigeria’s population, faces many of the same problems of environmental degradation, lack of jobs, and inadequate infrastructure. Northern Nigeria is also growing much faster than the south, with a total fertility rate of 6.6 children per woman, compared to 4.6 in the southern states. The median age of first-time mothers in northern Nigeria is only 18 years old.

Climate, Culture, and Discontent in the North

Last summer, in an offensive that stretched across four northern states, a hardline Islamist group called Boko Haram emerged suddenly to challenge the government, attacking police stations, barracks, and churches in escalating violence that claimed more than 700 lives, according to The Guardian. The government responded with a brutal crackdown, but recent targeted killings and a prison break seem to indicate the group is back.

Perhaps most distressingly, Boko Haram appears to have won some local support. Said one local cloth trader to The New York Times in an interview this October, “It’s the government’s fault. Our representatives and our government, they are not sincere. What one person acquires is enough to care for a massive amount of people.”

As in the south, mismanagement of natural resources has also played a role in creating a dangerous atmosphere of distrust in the government. After gold was discovered this spring in northwestern Nigeria, many under- and unemployed flocked to the region to try their luck, but they also unwittingly contaminated local water with high levels of lead. Although the state health officials say they have now identified more than 180 villages thought to be affected, the epidemic was only discovered after a French NGO stumbled upon it while testing for meningitis in June. More than 400 infant deaths have been connected to the mining, according to Reuters.

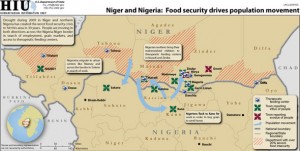

Contributing to natural resource-related misery in the north are climatic changes. Declining rainfall in the West African Sahel over the last century has pushed rain belts successively south, driving pastoralists into areas often already occupied. According to Anthony Nyong’s work, presented in ECSP Report 12, these changes have elevated competition over natural resources to the single most common cause of conflict in northern Nigeria in recent years. In addition to the long-term trend of declining rainfall, an acute drought in 2009 and another this year in neighboring Niger and Chad have created the worst food security crisis in 30 years. The droughts have also driven a great deal of cross-border migration into Nigeria, which itself saw lower than usual rainfall in the north, especially the northeast, around the ever-disappearing Lake Chad (see map above for resulting migration patterns).

In addition to the long-term trend of declining rainfall, an acute drought in 2009 and another this year in neighboring Niger and Chad have created the worst food security crisis in 30 years. The droughts have also driven a great deal of cross-border migration into Nigeria, which itself saw lower than usual rainfall in the north, especially the northeast, around the ever-disappearing Lake Chad (see map above for resulting migration patterns).

What rain did fall in the border areas fell suddenly and torrentially, causing rampant flooding that affected two million people. The floods not only caused physical damage but also came just before harvest season, destroying many crops and further reducing food security. Made more vulnerable by the number of displaced people and flooding, the area was then hit with its worst cholera outbreak in years, which has killed 1,500 people so far and spread south.

Cholera is not the only preventable disease to flourish in northern Nigeria in recent years. In 2003, cleric-driven fear of a U.S. plot to reduce fertility in Muslim women caused the widespread boycott of a UN-led polio vaccination drive. The fast-spreading disease then emerged in six of Nigeria’s neighbors where the disease had previously been eradicated. The northern states today remain the only consistently polio-endemic area in Africa, according to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

“A Stable Nigeria Is a Stable Africa”

Nigeria’s size and its wealth of natural resources make it a strategically important country for the future of the region. “A stable Nigeria is a stable Africa,” said Wilson Center scholar and former NEITI officer Uche Igwe in an interview. “Nigeria is 150 million people and the minute Nigeria becomes unstable, the West Africa sub-region will be engulfed.”

While there have been some strides in recent years in reducing corruption and addressing infrastructure needs (for example, NEITI’s work to promote revenue transparency), the development, health, environmental security, and human security situations remain dire in many parts of the country. With one of the fastest growing populations in the world and severe environmental problems in both the north and the south, scarcity will almost certainly be a challenge that Nigeria will have to face in the coming years. How the government responds to these challenges moving forward is therefore critical.

In 2008, in response to high oil prices, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown announced his intentions to send military aid to help combat Niger Delta militants. The statement was met with dismay from humanitarian organizations and caused the collapse of a ceasefire (which was then resumed for a time and now seems to be falling apart again). Brown was forced to backtrack into simply offering training support to Nigerian security forces.

In terms of U.S. assistance, USAID requested $560 million for Nigeria in FY 2010 – 75 percent of which is allocated towards HIV/AIDS – and the U.S. military has engaged in joint exercises with Nigerian forces. But so far, little has been done to integrate U.S. aid in a cohesive manner. Given the breadth of these issues, such integration is crucial.

“We need partners, like the United States and Europe, who have a stake in stability – in Nigeria, the Niger Delta, the Gulf of Guinea, and the world,” Igwe said. It remains to be seen what the Nigerian reaction would be to an offer of aid from the West that addresses not only the country’s security issues but also its myriad other problems, in a substantial and integrated fashion.

Part one on Nigeria’s future – The Delta – addresses oil, insurgency, and the environment in the south.

Sources: AFP, AFRICOM, AP, BBC, Global Polio Eradication Initiative, The Guardian, Independent, The New York Times, ReliefWeb, Reuters, SaharaReporters, USAID.

Photo Credit: “The Ranch,” courtesy of flickr user Gareth-Davies, and “Niger and Nigeria: Food security drives population movement,” courtesy of the U.S. State Department. -

Human and Climate Security in Africa

›A new study by the Strauss Center’s program on Climate Change and African Political Stability, “Locating Climate Insecurity: Where Are the Most Vulnerable Places in Africa?,” maps the regions of Africa most vulnerable to climate change based on four main indicators: (1) physical exposure to climate-related disasters; (2) household and community vulnerability; (3) governance and political violence; and (4) population density. Across all indicators, they found that the “areas with the greatest vulnerability are parts of Madagascar, coastal West Africa, coastal Nigeria, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.” The authors hope this paper will serve as a launching point for future research on the diverse regional causes of climate change vulnerability, ultimately guiding adaptation strategies across the continent.

“After the Rain: Rainfall Variability, Hydro-Meteorological Disasters, and Social Conflict in Africa,” by Cullen Hendrix and Idean Salehyan of the University of North Texas, examines how extreme weather events, rainfall, and water scarcity affect political stability in Africa. The authors found that rainfall has a “significant effect” on political conflict and that wetter years are also the more violent ones. However, they also found extreme variability between countries, with Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Mauritania, and Mozambique showing the strongest correlation between rainfall and conflict. This suggests that many local environmental and social factors were also affecting levels of violence. “Water scarcity can lead to resource competition, poor macroeconomic outcomes, reduced state capacity, and ultimately, social conflict,” the authors concluded. -

Colin Kahl on Demography, Scarcity, and the “Intervening Variables” of Conflict

› “One of the major lessons of 9/11 is that even superpowers can be vulnerable to the grievances emanating from failed and failing states,” said Colin Kahl, now deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East, at an ECSP event at the Wilson Center in October 2007. However, “if poverty and inequality were enough to lead to widespread civil strife, the entire world would be on fire.”

“One of the major lessons of 9/11 is that even superpowers can be vulnerable to the grievances emanating from failed and failing states,” said Colin Kahl, now deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East, at an ECSP event at the Wilson Center in October 2007. However, “if poverty and inequality were enough to lead to widespread civil strife, the entire world would be on fire.”

“I think any in-depth examination of particular cases shows that there’s a complex interaction between demographic pressures, environmental degradation and scarcity, and structural and economic scarcities – that they tend to interact and reinforce one another in a kind of vicious circle,” Kahl said.

“It’s really important to keep in mind that any attempt to address…environmental and demographic factors should focus not just on preventing environmental degradation, or slowing population growth, or increasing public health. They must also focus on those intervening variables in the middle that make certain societies and countries more resilient in the face of crisis.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

The Ultimate Weapon Is No Weapon: Human Security and the New Rules of War and Peace

›To understand the security concerns of the developing world, we must understand that lack of institutional capacity has created a “house of cards,” said U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Shannon Beebe, speaking at the Wilson Center on October 19. “When that card gets pulled out, the house is going to fall.”

Beebe, a senior Africa analyst for the Department of Defense, and Mary Kaldor, professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, discussed their new book, The Ultimate Weapon is No Weapon: Human Security and the New Rules of War and Peace, in which they argue for a broader conception of human security. “The world is suffering from a lack of a security narrative,” said Beebe.

“The ultimate weapon is not the F-22,” said Kaldor, “it is a change of mindset.”

Creating Pirates: Threats vs. Vulnerabilities

“What happens when a man is already a fisherman and you take all his fish away? You create a pirate,” said Beebe. The environmental and human security threat of overfishing in Somalia was not taken seriously as a security threat until it was left unchecked for 20 years and developed into a “real kinetic threat” of piracy, he said.

Beebe spent a year interviewing 80 to 90 Africans in 13 countries, including military leaders, academics, NGO leaders, and even Somali cabdrivers in the United States, about how they view their security. “What came back was resounding, sobering, and confusing,” said Beebe. Amongst those interviewed, few expressed traditional “kinetic” security concerns stemming from physical threats. Instead it was the “conditions-based vulnerabilities” — such as poverty, health, water and sanitation, gender equality, and climate change — that were identified as primary security threats.

“Until we stop giving Africans and the developing world our definition of what is right for their security and start listening to what they are saying is relevant to their security, we are going to continue to marginalize ourselves,” Beebe said.

Filling The Security Gap

There is currently “a profound security gap,” Kaldor said, and a failure to meet the diverse needs and root causes of violence in much of the developing world. Filling the security void has been an array of both good and bad actors – NGOs, humanitarian agencies, militias, and warlords. If we do not adapt our own security strategies to fill this gap, “it will be filled by someone [else],” Beebe warned.

Human security must be incorporated into our security narrative, Beebe and Kaldor argue in their book, which means addressing the security needs of individuals and communities, not just the state. It also involves protection from violence, material deprivation, and natural disasters. They advocate for more robust global emergency forces that would act as a global national guard or police force.

Integrating Human Security

Promoting the rule of law domestically and shifting interventions “from a war paradigm to a law paradigm” is crucial, said Kaldor. Furthermore, we must change our mindset so that we value the lives of those in foreign countries as highly as we value American or European lives. “You can’t bomb your own people,” she said.

Our greatest challenge, Beebe explained, is to shift our language from “siloed approaches” to create an interconnected, coherent security narrative. Beebe cited former General Anthony Zinni’s UMC (Ret.) incorporation of environmental security into U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) strategy during his tenure in the late 1990s as evidence of the possible success of integrated approaches. More recently, the Belgian High Command adopted a human security policy, said Kaldor.

While human security is already being taken into account on the ground, “it is very much organic, rather than institutionalized…we understand that there is an imperative but again it is the security narrative that is lacking,” said Beebe. Only by engaging with individuals and taking their needs into account with a more comprehensive security narrative can we foster lasting and sustainable security, he said.

Photo Credit: “Elderly Woman Receives Emergency Food Aid,” courtesy of flickr user United Nations Photo. -

Assessing Our Impact on the World’s Rivers

› In a special “Rivers in Crisis” issue of Nature, the lead article, “Global Threats to Human Water Security and River Biodiversity,” presents damning evidence that manipulation of river systems — through the construction of canals, levees, hydroelectric projects, and other infrastructure — has caused serious and lasting biological damage to watersheds throughout both the developing and developed worlds. The authors (all 11 of them!) report that key rivers have become shadows of their former selves in terms of the amount of aquatic life they can support. Without drastically improved stewardship of waterways, “we are pushing these river systems toward catastrophe,” warns Peter McIntyre, an article co-author.

In a special “Rivers in Crisis” issue of Nature, the lead article, “Global Threats to Human Water Security and River Biodiversity,” presents damning evidence that manipulation of river systems — through the construction of canals, levees, hydroelectric projects, and other infrastructure — has caused serious and lasting biological damage to watersheds throughout both the developing and developed worlds. The authors (all 11 of them!) report that key rivers have become shadows of their former selves in terms of the amount of aquatic life they can support. Without drastically improved stewardship of waterways, “we are pushing these river systems toward catastrophe,” warns Peter McIntyre, an article co-author. The human impact on the world’s river systems will be hard to reverse, says Margaret Palmer, author of a second Nature article on freshwater biodiversity loss, “Beyond Infrastructure.” Human-induced changes to watersheds affect local hydrology at a fundamental level, she contends, weakening rivers’ ability to deliver crucial “ecological goods and services” — such as clean water and nutrient-rich sediment loads — that help maintain the health of local environments and the human populations that depend on them. To fully understand the scope of the problem, Palmer says more research is needed to explore the linkages between biodiversity levels and “ecosystem services” that healthy rivers provide.

The human impact on the world’s river systems will be hard to reverse, says Margaret Palmer, author of a second Nature article on freshwater biodiversity loss, “Beyond Infrastructure.” Human-induced changes to watersheds affect local hydrology at a fundamental level, she contends, weakening rivers’ ability to deliver crucial “ecological goods and services” — such as clean water and nutrient-rich sediment loads — that help maintain the health of local environments and the human populations that depend on them. To fully understand the scope of the problem, Palmer says more research is needed to explore the linkages between biodiversity levels and “ecosystem services” that healthy rivers provide. -

Admiral Mullen and the “Strategic Imperative” of Energy Security

›October 13, 2010 // By Geoffrey D. DabelkoTop American military brass weighed in this morning on energy security with an emphasis on conservation, efficiency, and alternatives. A little climate change even crept into the discussion as well.

The occasion was a Department of Defense conference titled “Empowering Defense Through Energy Security” sponsored by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics and the United States Air Force, Army, Navy and Marine Corps leadership. The new Office of Operational Energy Plans and Programs was on point.

Starting at the top, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen set the tone:My friend and columnist Tom Friedman has spoken eloquently of the growing need – and awareness – to rethink our views on energy – and minimize our dependence on overseas energy sources that fuel regimes that do not always share our interests and values, while not further damaging a world that is already becoming overheated, overpolluted, and overstretched.

The wider context of climate change and its security implications also found a place in Admiral Mullen’s remarks:

We in the Defense Department have a role to play here – not solely because we should be good stewards of our environment and our scarce resources but also because there is a strategic imperative for us to reduce risk, improve efficiencies, and preserve our freedom of action whenever we can. …

So, to start with, let’s agree that our concept of energy must change. Rather than look at energy as a commodity or a means to an end, we need to see it as an integral part of a system … a system that recognizes the linkages between consumption and our ability to pursue enduring interests.

When we find reliable and renewable sources of energy, we will see benefit to our infrastructure, our environment, our bottom line … and I believe most of all … our people. And the benefits from “sustainability” won’t just apply to the military.Beyond these immediate benefits, we may even be able to help stem the tide of strategic security issues related to climate change.

Admiral Mullen then gave way to General Norton A. Schwartz, chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force; General Peter W. Chiarelli, vice chief of the U.S. Army; Aneesh Chopra, the federal chief technology officer; and Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, with Sharon Burke, director of operational energy plans and programs, running the show.

This is no small matter. In addition to the newly developing waterways near the polar icecaps, in 2008, the National Intelligence Council identified twenty of our bases that are physically at risk as a result of the rising level of the ocean.

And regardless of what the cause of these changes is – the impacts around the world could be sobering – and far-reaching.

As glaciers melt and shrink at a faster rate, water supplies have been diminishing in parts of Asia.

Rising sea levels could lead to mass migration and displacement similar to what we have seen in Pakistan’s flood … and climate shifts could drastically reduce the arable land needed to feed a burgeoning population as we have seen in Africa.

This scarcity of – and potential competition for – resources like water, food, and space – compounded by an influx of refugees if coastal lands are lost … could not only create a humanitarian crisis, but create conditions of hopelessness that could lead to failed states … and make populations vulnerable to radicalization.

These challenges highlight the systemic implications – and multiple-order effects – inherent in energy security and climate change.

And while the brass met inside, clean energy companies exhibited their wares in the Pentagon’s inside courtyard.

Photo Credit: “the Pentagon from above,” courtesy of flickr user susansimon. -

Welcome Back, Roger-Mark: A Powerful Voice Returns to PHE

›October 13, 2010 // By Geoffrey D. Dabelko“I’m thrilled to be back.” That was the sentiment that Roger-Mark De Souza relayed to me, in his famous lilting baritone, about becoming the new vice president of research and director of the climate program at Population Action International (PAI). De Souza has long been a leading voice on integrated development programs that feature population, health, and environmental (PHE) dimensions. But three years as the Sierra Club’s director of foundations and corporate relations took him away from day-to-day work on these issues.

In his new posts, Roger-Mark will lead PAI’s research team in establishing a strong evidence base and engaging new allies in the effort to support healthier women and families, according to PAI. “Roger-Mark’s diverse research experience makes him an ideal fit for PAI as we undertake critical projects on reproductive health, population and environment issues,” said PAI President and CEO Suzanne Ehlers in a press release.PAI is a research-based advocacy NGO long known for innovative work connecting demographic considerations with other key development realms: mainly environment, security, and poverty. PAI’s policy-friendly briefs on population’s links with water, forests, and biodiversity provide practical meta-analysis of these complex and evolving connections. The organization’s more recent work on demographic security has been instrumental in advancing research and policy in that largely neglected arena.

De Souza captured his insights last year for our Focus series, in his brief, “The Integration Imperative – How to Improve Development Programs by Linking Population, Health, and Environment” (see also his follow-up interview on NSB). He combines lessons learned from community-based development efforts in Southeast Asia and East Africa with a savvy sense of the policy debates among donors and recipient countries alike.

This move reunites De Souza with Kathleen Mogelgaard, with whom he made key contributions to the PHE field as colleagues at Population Reference Bureau earlier this decade, and who is now Senior Advisor for Population, Gender, and Climate at PAI.

De Souza returns to his former focus on PHE issues at a time when the field is collectively searching for the best ways to respond to the challenges of climate mitigation and adaptation, as well as ongoing hurdles such as scaling up, sustainability, and labeling.