-

Saleem Ali at TEDxUVM on Environmental Peacemaking

›“The use of the term ‘peace’ is in many circles still considered taboo, because immediately people think you are talking about something that is utopian,” said University of Vermont Professor Saleem Ali at a recent TEDx event on sustainability. “But I’m here to tell you that peace is pragmatic. Peace is possible.”

Ali points out the value of peace to every sector of society and, using an example from Ecuador and Peru, argues for the utility of the environment as a peacemaker. Other longstanding conflict areas like Cyprus, Iraq, Israel, and Korea are also ripe for environmental peacebuilding efforts, he says.

Professor Ali has written for The New Security Beat before on the strengths and weaknesses of viewing conservation and sustainability efforts through a strictly security lens. He points out that environmentalists must tread a fine line when assigning causality between the environment and conflict, but even when natural resources or climate are not central to a conflict, environmental peacebuilding can still play a role in creating shared ground (sometimes literally) between combatants.

“Treasures of the Earth,” Ali’s latest book, examines the thorny subject of how best to balance resource extraction in developing countries with long-term sustainability. Recent examples, such as Angola and Liberia’s blood diamonds, the DRC’s conflict minerals, and concerns over Afghanistan’s potential reserves have shown the difficulty in striking that balance.

“Ultimately, conflict trumps everything else” in terms of what we ought to be concerned with, Ali argues, and therefore, anyone, no matter their profession or capacity, should keep the pursuit of peace in mind – and all options on the table – when making decisions that affect others. -

The Dead Sea: A Pathway to Peace for Israel and Jordan?

›September 7, 2010 // By Russell SticklorThe Middle East is home to some of the fastest growing, most resource-scarce, and conflict-affected countries in the world. New Security Beat’s “Middle East at the Crossroads” series takes a look at the most challenging population, health, environment, and security issues facing the region.

Amidst the start of a new round of Middle East peace negotiations, the fate of the Dead Sea — which is divided between Israel, Jordan, and the West Bank — may not seem particularly relevant. But unlike the perpetually thorny political issues of Israeli settlement policy and Palestinian statehood, the Dead’s continuing environmental decline has sparked rare consensus in a region beset by conflict. Israelis, Jordanians, and Palestinians all agree that something must be done. The much more difficult question, however, is what. But no one is lacking for ideas.Who Stole the Dead’s Water?

Some 1,400 feet below sea level, the shoreline of the Dead Sea lies at the lowest dry point on the planet. Since the 1970s, this ancient inland saltwater sea has been changing, and fast, with the water level dropping at a rate of three feet per year. The region’s stifling heat and attendant high evaporation rates have certainly played their part. But the real culprits are irrigated agriculture and household water demand, spurred by population growth, which have siphoned off much of the precious little water that once flowed into the sea.

Historically, the Jordan River and its tributaries have contributed roughly 75 percent of the Dead’s annual inflow, or about 1.3 billion cubic meters per year. Even though the Jordan isn’t a large river system, it is an economic lifeline in this parched region. The basin’s waters have been tapped to the point of exhaustion by businesses, farms, and households in Israel, Jordan, the West Bank, and, father afield, Syria and Lebanon. With the cumulative population of those areas projected to increase by 68 percent between now and 2050 (or from 44.9 million today to 75.4 million by mid-century), strain on the region’s water supply will only increase with each passing year.

Already, the Jordan and its tributaries are far worse for the wear. Pollution is an ongoing concern thanks to untreated wastewater entering the river system, while a sprawling network of dams and other irrigation diversions to “make the desert bloom” has carried with it a hefty environmental price tag. The Jordan now delivers a scant 100 million cubic meters to the Dead each year, with up to 50 percent of that flow likely contaminated by raw sewage due to inadequate wastewater treatment upstream.

Meanwhile, water depletion rates in the Dead have been exacerbated by mineral-extraction companies on the sea’s southern reaches, which rely heavily on evaporation ponds to remove valuable minerals from the saltwater.

Tapping the Red

Attempts to internationalize the environmental dilemmas facing the greater Dead Sea region range from a proposed transborder “peace park” in the Jordan River valley to a global, internet-driven campaign to vote the Dead Sea as one of the seven natural wonders of the world. But by far the most ambitious — and controversial — idea for restoring the Dead Sea’s health is to build a 186-mile canal to bring in water from the Red Sea.

The plan has been around for decades, but has not gotten off the drawing board due to its large scale and costs. The project’s centerpiece would be a waterway built through the Arava Desert Valley along the Israeli-Jordanian border. Proponents on both sides of the border say the canal could help raise the Dead’s surface level, helping restore the area’s struggling ecosystems. And given the canal’s substantial elevation drop from sea level to shoreline, its waters could likely be harnessed for hydroelectricity, powering desalination plants that would provide new fresh water for the region.

The project could also harness cross-border environmental issues to transcend long-standing political and religious divisions between the region’s Jewish and Arab populations. “People are saying that water will cause wars,Dr. Hazim el-Naser in a 2002 interview on the canal project, when he served as Jordanian minister of water and irrigation. “We in the region, we’re saying, ‘No.’ Water will enhance cooperation. We can build peace through water projects.” Currently, the canal proposal is the subject of a World Bank feasibility study expected to be completed in 2011.

Deep Skepticism Remains

Still, as diplomatically and environmentally promising as a Red-Dead canal may seem, not everyone is on board with the proposed project. Environmentalists’ concerns run the gamut from unintended ecological impacts on the Dead Sea’s delicate chemical composition, to a sense that, even after decades of on-and-off consideration, the project is being pushed at the expense of other possible policy options.

The New Security Beat recently contacted Mira Edelstein of the international environmental nonprofit Friends of the Earth Middle East via email to discuss some of the group’s concerns about the canal. Edelstein highlighted some of the potential pitfalls of — and alternatives to — a canal link to the Dead:

New Security Beat: How have population growth and the corresponding rise in food demand in Israel, Jordan, and the West Bank affected the Dead Sea’s health?Mira Edelstein: The Jordanian and Israeli agricultural sectors still enjoy subsidized water tariffs, making it easy to continue growing water-intensive crops. But this depletes flows in the lower Jordan River system, and directly impacts the Dead Sea.

NSB: Why is your organization opposed to the idea of a Red-Dead canal link?ME: Friends of the Earth Middle East does not support a Red Sea link, as this option carries the risk of irreparable damage. We believe that this option will not only damage the Dead Sea itself — where the mixing of waters from two different seas will surely impact the chemical balance that makes the Dead Sea so unique — but also because we are worried that pumping such an enormous amount of water from the Gulf of Aqaba will likely harm the coral reefs in the Red Sea itself.

NSB: What steps do you propose to improve environmental conditions in the Dead Sea and the Jordan River valley?

Additionally, the Arava Desert Valley, where the pipes will be laid, is a seismically active region. Any small earthquake might damage the pipes, causing seawater to spill and polluting underground freshwater aquifers.ME: It all has to do with the water policies in the region. The governments [of Israel, Jordan, and the West Bank] desperately need to reform our unsustainable policies, and at the top of this list is agriculture. This means removing water subsidies and changing over from water-intensive crops to more sustainable crops appropriate for the local environment.

Sources: Friends of the Earth Middle East, Israel Marine Data Center, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, National Geographic, the New York Times, Population Reference Bureau, United Nations, Washington Post, Waternet, the World Bank.

In addition, wastewater treatment plants need to be built throughout all of the Jordan valley region so that only treated wastewater is used for agriculture. Some of that treated water, and of course fresh water, should be brought back into the Jordan River system that will later flow into the Dead Sea…In addition, ecotourism projects should be encouraged, as they are an economic stimulus that can help support greater environmental conversation in the region.

Photo Credit: “Dead Sea Reflection,” looking east across the Dead Sea to the Jordanian shore, courtesy of flickr user Mr. Kris. -

Interview With Wilson Center’s Maria Ivanova: Engaging Civil Society in Global Environmental Governance

›August 13, 2010 // By Russell SticklorFrom left to right, the five consecutive Executive Directors of the United Nations Environment Programme: Achim Steiner, Klaus Toepfer, Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Mostafa Tolba, and Maurice Strong, at the 2009 Global Environmental Governance Forum in Glion, Switzerland.

In the eyes of much of the world, global environmental governance remains a somewhat abstract concept, lacking a strong international institutional framework to push it forward. Slowly but surely, however, momentum has started to build behind the idea in recent years. One of the main reasons has been the growing involvement of civil society groups, which have demanded a more substantial role in the design and execution of environmental policy—and there are signs that environmental leaders at the international level are listening.

On the heels of the UN Environment Programme’s Governing Council meeting earlier this year in Bali, a call was put out to strengthen the involvement of civil society organizations in the current environmental governance reform process. To that end, UNEP is creating a Civil Society Advisory Group on International Environmental Governance, which will act as an information-sharing intermediary between civil society groups and regional and global environmental policymaking bodies over the next few years. (The application deadline has been extended; applicants interested in joining the Advisory Group should submit their materials via e-mail by Sunday, August 15, 2010—full instructions are listed at the end of this post.)

Maria Ivanova, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and director of the Global Environmental Governance Project, played a key role in ensuring civil society engagement in the contemporary political process on international environmental governance reform. Ivanova recently sat down with the New Security Beat to talk about the future prospects for global environmental governance, the Rio+20 Earth Summit in Brazil in 2012, and how to foster a more open and sustained dialogue between the worlds of environmental policymaking and academia.

New Security Beat: What are the pitfalls of a regional approach to addressing climate change and other environmental issues, as opposed to an international approach?

Maria Ivanova: Global environmental problems cannot be solved by one country or one region alone, and require a collective global response. But they can also not be addressed solely at the global level because they require action by individuals and organizations in particular geographies. The conundrum with climate change is that the countries and regions most affected are the ones least responsible for causing the problem in the first case. We cannot therefore simply substitute a national or regional response for a global action plan, as more often than not, it would be a case of “victim pays” rather than “polluter pays”—the fundamental principle of environmental policy in the United States and most other countries. Importantly, however, our global environmental institutions do not possess the requisite authority and ability to enforce agreements and sanction non-compliance.

NSB: What are some of the inherent difficulties in getting countries to see eye-to-eye and collaborate on the development of institutions for global environmental governance?

MI: The most important difficulty is perhaps the lack of trust and a common ethical paradigm accompanied by a pervasive suspicion about countries’ motives. Secondly, there is a perceived dichotomy between environment and development that has lodged in the consciousness of societies around the world. Thirdly, there’s the inability of current institutions to deliver on existing commitments. The resulting blame game feeds suspicions and restarts the whole cycle again.

NSB: Do you see the 21st century’s various environmental challenges as being a driver of international conflict or cooperation?

MI: After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was expected that global environmental (and other) issues would be a driver for cooperation. A green dividend was expected, and the 1992 Rio Earth Summit fostered much hope. But quite the opposite happened. Global environmental challenges such as climate change, for example, have caused more conflict than cooperation. Other concerns, such as whaling and biodiversity loss, have also triggered conflicts as governments have become fiercely protective of their national sovereignty. On the other hand, civil society groups and even individuals around the world have come together in new coalitions and formed new alliances. So while at a governmental level we observe increased tension, at a civil society level, we witness unprecedented mobilization and collaboration, especially through social media. Obviously, we live in a new world.

NSB: There has been a lot of talk about bridging the gap between the academic and policy worlds—two communities that do not typically have much interaction, but likely have a lot to learn from one another. What steps do you think can be taken regarding environmental governance that might facilitate a sustained dialogue and interaction between the two sides?

MI: Many academics have thought, debated, and written about global environmental governance. Fewer have presented their analysis to policymakers and politicians. At the Global Environmental Governance (GEG) Project that I direct, we seek to bridge that gap and provide a clearinghouse of information, serving as a “brutal analyst,” and acting as an honest broker among various groups working in this field. Moreover, we are in the process of launching a collaborative initiative among the Global Environmental Governance Project, the Center for Law and Global Affairs at Arizona State University, and the Academic Council on the UN System to collect, compile, and communicate academic thinking on options for reform to the ongoing political process on international environmental governance. We are creating a Linked-In group where we hope to engage in discussions with colleagues from universities around the world with the purpose of generating ideas, developing options, and testing them with policymakers. Moreover, we are engaging with civil society beyond academia. The GEG Project is sponsoring five regional events on governance in Argentina, China, Ethiopia, Nepal, and Uganda that are taking place in August and September. Led by young environmental leaders in those countries who attended the 2009 Global Environmental Governance Forum in Glion, Switzerland, these consultations are generating genuine engagement in thought and action on governance. So, new initiatives are certainly emerging and the results could be visible by the Rio+20 conference in May 2012.

NSB: What are your expectations for Rio+20?

MI: Given that governance is a major issue on the agenda for Rio+20, my hope is that the conference will bring about a new model for global governance, which reframes the environment-development dichotomy, cultivates shared values, and fosters leadership. Indeed, I am convinced that leadership is the most important necessary condition for change. We need to encourage more bold, visionary, entrepreneurial behavior rather than conformity.

My hidden hope for Rio+20 is that it will dramatically shift the narrative and move us from sustainable development to sustainability. Sustainability builds on sustainable development but goes further than that. As a concept it allows for new thinking, new actors, and new politics. It avoids the North-South polarization of sustainable development, which is so often equated with development and is therefore understood as what the North has already attained and what the South is aspiring to. By contrast, no one society has reached sustainability, and learning by all is necessary. Moreover, much of the innovative thinking about sustainability is happening in developing countries, which are trying to improve quality of life without jeopardizing the carrying capacity of the environment. Progressive thinking is also taking place on campuses in industrialized countries, which are creating a new sense of community and collaboration. Indeed, young people around the world are engaging in finding new ways of living within the planetary limits in a responsible and fulfilling manner.

Maria Ivanova is director of the Global Environmental Governance Project, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and an assistant professor of global governance at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston.

If you wish to nominate yourself or someone else as a candidate for the Civil Society Advisory Group on IEG, you need to submit materials to civil.society@unep.org by Sunday, August 15, 2010 (please copy info@environmentalgovernance.org). You can find the nomination form and the Terms of Reference for the group at the Global Environmental Governance Project’s website.

Photo Credit: “UNEP Leadership,” courtesy of the Global Environmental Governance Project. -

Ban Ki-moon: Natural Resources Should Be Part of Peacebuilding

›July 30, 2010 // By Schuyler NullNatural resource management is a critical component of the peacebuilding process according to a new report from UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. The report, presented to the UN Security Council and General Assembly this month, is a follow-up to last year’s presentation by the Secretary-General’s office on peacebuilding in the immediate aftermath of conflict.

The Secretary-General singles out the 2009 UN Environment Programme (UNEP) study “From Conflict to Peacebuilding: The Role of Environment and Natural Resources” for demonstrating the recent links between land use, natural resources, frequency of conflict, and conflict relapse. The Secretary-General writes:44. I wish to highlight two areas of increasing concern where greater efforts will be needed to deliver a more effective United Nations response. First, natural resources: a recent study by the United Nations Environment Programme concluded that 40 per cent of internal conflicts over a 60-year period were associated with land and natural resources, and that this link doubles the risk of conflict relapse in the first five years. Efforts have been made to draw early attention to these risks and to improve inter-agency coordination to address them, including by strengthening national capacity to prevent disputes over land and natural resources, as described in paragraph 31 above. Examples include programmes in Afghanistan, Timor-Leste and the Sudan, where coordination among several United Nations entities addressing land and natural resource management has demonstrated the importance of an inclusive approach. In order to further deliver on the ground I call on Member States and the United Nations system to make questions of natural resource allocation, ownership and access an integral part of peacebuilding strategies.

ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko calls the inclusion of this language “an important step towards integrating environmental issues into broader UN peacebuilding efforts and providing critical top-level political support for this integration effort.”

UNEP’s Post-Conflict and Disaster Management Branch (PCDMB) has been working to support a variety of UN bodies on integrating environment and natural resources into the peacebuilding process. Recent PCDMB efforts have been based in Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Sierra Leone, the DRC, and Sudan. New Security Beat asked UNEP PCDMB’s Director of Policy and Planning David Jensen to reflect on the new report via email:I’m thrilled to finally see that after over 10 years of work by UNEP and a variety of other organizations and scholars, these issues have finally been recognized at the highest political level. There is no longer any doubt that the mismanagement of natural resources can be a key factor in contributing to violent conflict. At the same time, the very recognition that environmental issues and natural resources can contribute to violent conflict underscores their potential significance as pathways for cooperation, transformation, and the consolidation of peace in war-torn societies.

As Jensen writes in ECSP Report 13, “If people cannot find clean water for drinking, wood for shelter and energy, or land for crops, what are the chances that peace will be successful and durable? Very slim.”

Last fall, Jensen predicted the UN was finally approaching a fundamental tipping point for inclusion of natural resource issues in the broader peacebuilding process, and the Secretary-General appears to have proven him right.

Photo Credit: “Secretary-General Addresses General Assembly,” courtesy of flickr user United Nations Photo.Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina: Why a Melting Arctic Needs Stronger Governance

›May 11, 2010 // By Schuyler NullThe Arctic Council, which helps broker economic and environmental agreements between the Arctic nations, needs a larger role in developing joint international policy, says Norway’s ambassador to Canada. Accelerating ice melt is expected to open the Arctic Ocean to seasonal ship traffic sometime between 2013 and 2030 – which analysts worry will lead to disputes over newly accessible oil and gas reserves.

The Arctic Council was founded in 1996 to “provide a means for promoting cooperation, coordination and interaction among the Arctic States” – Canada, Greenland, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, the United States, as well as some Arctic indigenous communities are all members. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the Arctic may contain up to 90 billion barrels of oil (more than the known reserves of Nigeria, Kazakhstan, and Mexico combined) and 27 percent of the world’s known natural gas reserves, most of which is located offshore.

While rhetorical flare-ups over access to resources and accusations of militarization have occurred, to date the Arctic Council has been an effective mitigating body. However, the Council currently lacks a permanent secretariat and reliable funding.

Currently, any territorial disputes are handled under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), while the Arctic Council mainly facilitates communication. However the United States has not yet ratified the Law of the Sea, despite concerted high-level efforts to do so.

Referring to the Arctic, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recently told Congress that “the Law of the Sea provides commercial rights to the mining of what is in the seabed of the territories that are claimable under sovereignty provisions in the treaty,” and if the United States does not ratify it, “we will lose out, in economic and resource rights, in terms of environmental interests, and national security.”

While the National Intelligence Council predicts that a major armed conflict over the Arctic is unlikely in the near future, it suggests that “serious near-term tension could result in small-scale confrontations over contested claims.” A comprehensive agreement brokered by Arctic Council leadership and agreed upon by all members – like the Convention on the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution, and Protocols, which helps regulate commerce and environmental protections – would guarantee third-party moderation and alleviate the risk of an outstanding dispute erupting into real conflict.

The value of such an agreement is illustrated by the growing tension between Britain and Argentina over offshore oil rights around the Falkland Islands. Recent British drilling efforts, which have yielded a pocket of oil worth potentially an estimated $25 billion, provoked a furious response from Argentinean officials who have long disputed Britain’s claims to sovereignty, not only of the islands themselves, but of the seas around them.

Under UNCLOS, a nation is entitled to “explore and exploit” any natural resources within 200 nautical miles of their shores and in certain circumstances can apply for an extension to 350 nautical miles. By these definitions, there is considerable overlap in British and Argentinean claims, which the Law of the Sea alone is unable to resolve.

In a statement reported by the Times Online last week, Foreign Minister Jorge Taiana said that “Argentina energetically refutes what is an illegal attempt to confiscate non-renewable natural resources that are the property of the Argentine people.”

In an earlier bid to slow development, Argentinean President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner announced in February that any ship coming to or from the disputed islands would have to be granted a permit in order to pass through Argentinean waters, effectively threatening blockade.

The sovereignty of the Falkland Islands has remained a disputed topic for Argentina since the loss of the Falkland Islands War in 1982, made worse by recent financial woes at home and the country’s lack of domestic oil reserves.

Although tensions in the Arctic region are low now, a changing environment and increased competition for energy resources may lead to similar disputes in the polar region – a strong argument for strengthening multilateral institutions like the Arctic Council and UNCLOS sooner rather than later.

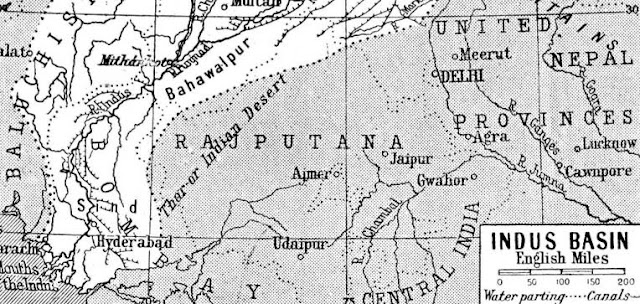

Video Credit: “2008 Arctic Sea Ice Minimum w/overlay” courtesy of Flickr user NASA Goddard Photo and Video.Parched and Hoarse, Indus Negotiations Continue to Simmer

›April 30, 2010 // By Julien KatchinoffBrewing conflicts over water in South Asia are not new to the readers of the New Security Beat. Violence due to variations in the monsoon season , high tensions over water and energy diplomacy, and pressures stemming from mismanaged groundwater stocks in the face of burgeoning population growth have all been reported on before.

The latest addition to this thread is disappointingly familiar: escalating tensions between Pakistan and India over the Indus river basin. Pakistan views Indian plans to construct the Nimoo-Bazgo, Chutak, and Kishanganga power plants as threatening the crucial water flows of an already parched nation according to objections voiced by the Pakistani Water Commission at the annual meeting of the Indus Water Commission in March. As a result, all efforts to reach an agreement on India’s plans for expanded hydroelectric and storage facilities in the basin’s upstream highlands failed.

In a recent editorial in the Pakistani newspaper The Dawn , former Indus River System Authority Chairman Fateh Gandapur claimed that new construction amounts to a clear violation of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT):“India is building large numbers of dams …on the rivers Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej and Beas, including on their tributaries in Indian-administered Kashmir. Together, these will have the effect of virtually stopping the perennial flow of water into Pakistan during a period of six to seven months that include the winter season. Not only will this be a blatant violation of the IWT and international laws on water rights of lower riparian areas, it will also amount to making Pakistan dry and, in the future, causing water losses that will deprive this country of its rabi and kharif crops. Our part of Punjab, which has a contiguous canal irrigation system that is amongst the largest in the world, will be turned into a desert.”

Gandapur’s fears, shared by many in Pakistan, are borne out of the desperate situation in which many of their compatriots live. As noted in Running on Empty: Pakistan’s Water Crisis, a report by the Wilson Center’s Asia program, water availability in the country has plummeted from about 5,000 cubic meters (m3) per capita in the early 1950s to less than 1,500 m3 per capita today–making Pakistan the most water stressed country in Asia. With more than 90% of these water flows destined for agricultural use, only 10% remains to meet the daily needs of the region’s booming population. This harmful combination of low supplies and growing demand is untenable and in Karachi results in 30,000 deaths–the majority of which are children–from water-borne illnesses each year.

This harmful combination of low supplies and growing demand is untenable, and may be get worse before it gets better, as Pakistan’s population is projected to almost double by 2050. At an upcoming conference at the Wilson Center, “Defusing the Bomb: Pakistan’s Population Challenge,” demographic experts on Pakistan will address this issue in greater detail.

Recent talk of ‘water wars’ and ‘Indian water jihad’ from Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, the founder of Lashkar-e-Taiba and head of Jamaat-ud-Dawah, have played upon popular sentiments of distrust and risk inflaming volatile emotions, the South Asian News reports.

Harvard’s John Briscoe, an expert with long-time ties to both sides of this dispute, sees such statements as the inevitable result of the media-reinforced mutual mistrust that pervades the relationship of the two nations and plays on continued false rumors of Indian water theft and Pakistani mischief. “If you want to give Lashkar-e-Taiba and other Pakistani militants an issue that really rallies people, give them water,” he told the Associated Press.

The rising tensions have echoed strongly throughout the region. For the first time in its 25-year history, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has raised the water issue (long thought to be a major political impediment and contributor to SAARC’s stagnation) among its members during its meeting this week. “I hope neighbors can find ways to compartmentalize their differences while finding ways to move forward. I am of course referring to India and Pakistan,” said Maldives President Mohammed Nasheed, during his address on Wednesday. “I hope this summit will lead to greater dialogue between (them.)”

Prime ministers Manmohan Singh and Yousuf Raza Gilani heeded the calls and responded with a hastily arranged in-person meeting on the sidelines of the SAARC conference. The emerging agreement targeted a comprehensive set of issues, including water and terrorism, and, while unsurprisingly weak on action, set a path upon which the nations can begin to move forward. Speaking about the agreement’s significance, Indian Foreign Secretary Nirumpama Rao told the Los Angeles Times, “There’s been a lot of soul-searching here. We need to take things forward. This is good for the two countries and good for the region.”

The fragile détente faces great hurdles in the months to come, especially if rainfall remains scarce as forecasters predict. Already, local communities in India and Pakistan are venting frustrations over water shortages. On Thursday, just one day after the agreement between Prime ministers Singh and Gilani, several Bangalore suburbs staged protests at the offices of the local water authorities, complaining loudly about persistent failures of delivery services to produce alternative arrangements for water provision despite regular payments by local citizens. Whether local civil action ultimately helps or hinders bilateral water cooperation between India and Pakistan will be interesting to track in the near future and we at the New Security Beat look forward to continuing to engage with readers on the latest developments.

Photo Credit: Mahe Zehra Husain Transboundary Water Resources Spring 2010High Altitude Turbulence: Challenges to the Cordillera del Cóndor of Peru

›In 1998, Peru and Ecuador settled a long-running border dispute in the Cordillera del Cóndor mountain range that had killed and wounded dozens on both sides in 1995. In addition to pledging renewed cooperation on deciding the final placement of the border, the agreement, the Acta Presidencial de Brasilia, committed both sides to establishing extensive ecological protection reserves on both sides of the border: A peace park of sorts was born.

But now, indigenous groups fear that extractive industries in the area could threaten both the biodiversity and the ecological integrity of the forests and streams that they rely upon for their survival. They detail these charges in a new report, Peru: A Chronicle of Deception, and in a new video documentary, “Amazonia for Sale.”

Located on the eastern slopes of the Equatorial Andes, the area is a recognized global biodiversity hotspot with large areas of pristine montane habitat. In 1993-4, Conservation International led a biodiversity assessment trip to the area and identified dozens of species new to science. Their report, The Cordillera del Cóndor Region of Ecuador and Peru: A Biological Assessment, noted the “spectacular” biodiversity of the area, and its key role in the hydrological cycle linking the Andes with the Amazon.

Recognizing the region’s importance, the Acta Presidencial de Brasilia stipulated the need to create and update mechanisms to “lead to economic and social development and strengthen the cultural identity of native populations, as well as aid the conservation of biological biodiversity and the sustainable use of the ecosystems of the common border,” wrote Martin Alcade et al. in the ECSP Report.

Indigenous communities in Peru are accusing the Peruvian government of reneging on those promises by allowing extractive industries extensive access to the region. They charge that the government gave in to gold mining interests who want to reduce the size of the protected area in the Cordillera del Cóndor. They also claim that the Peruvian government is violating promises made to include indigenous peoples in the governance and management of the area.

Carefully managing extractive activities was a key priority for Peru and Ecuador when they negotiated an end to their border dispute. A management plan for the area with strong protection for key biodiversity areas was supposed to ensure everyone’s interests.

However, Peru’s current president, Alan Garcia, has been aggressive in promoting extractive industries in Peru,to the point of inciting significant popular opposition among many indigenous peoples. Less than a year ago, protests over oil exploration in Amazonian lowlands city of Bagua killed and wounded dozens of Peruvians. This violence followed years of social conflict over mining development in a number of communities in Peru’s Andean highlands.

Earlier this decade, Peru made some progress in resolving extractive disputes. But Garcia’s strong promotion of the extractive sector in the face of indigenous opposition, like we currently see in the Cordillera del Cóndor region, suggests years of confrontations to come.

Tom Deligiannis is adjunct faculty member at the UN-mandated University for Peace in Costa Rica, and an associate fellow of the Institute for Environmental Security in The Hague.

Photo Credit: “El vuelo del condor, acechando a su presa,” courtesy of flickr user Martintoy.Demobilized Soldiers Developing Water Projects – and Peace

›Can demobilized ex-combatants help improve water resources in post-conflict countries? Last fall, the Global Water Institute (GWI) held a symposium in Brussels to find out.

Seventy representatives from the African Union, the United Nations, civil society, research institutes, and EU water policy advisors discussed ways in which former soldiers could be employed in the water sector to create peace dividends, bridge divided societies, and improve water security in countries recovering from conflict.

GWI, which is headquartered in Brussels and led by Valerie Ndaruzaniye, formerly of the Institute of Multi-Track Diplomacy’s Global Water Program, hopes to use the water sector development to meet multiple objectives in post-conflict reconstruction, such as:- increasing environmental security,

- reducing the likelihood of future conflict over water,

- enhancing security and stability, and

- employing demobilized ex-combatants to create peace dividends.

While disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR), is a fairly new process in post-conflict settings (the first program took place only 15 years ago), it has progressed rapidly in recent years, moving from a primarily military exercise to one focused on reintegration. Reintegration has also shifted from its exclusive focus on the ex-combatants, which often caused resentment in conflict-affected communities, to include women, children, youth, and the elderly and disabled, as well as the affected communities.

Reintegration is still the most difficult stage of any DDR program, not only for budgetary and political reasons, but also due to the processes of transitional justice and reconciliation. Through experience in the field, practitioners have realized that such programs are not simply technical exercises and must be better linked to wider recovery efforts and development programs for more sustainable results.

By supporting sustainable development in the water sector, and simultaneously contributing to reconciliation and peace dividends by involving ex-combatants in community development work, GWI can offer a substantial contribution to the reintegration process.

“Making the link between water management and DDR is a novel idea. GWI is a good example of integration of policy areas in order to build peace in some countries,” said Catherine Woolard, the director of the European Peacebuilding Liaison office.

Adrienne Stork is currently working on natural resource management and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration programs jointly with the UNDP Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery and the UNEP Disasters and Conflicts Unit in Geneva, Switzerland.

Photo Credits: Flickr User ISAFMEDIA, 080816-N-8726C-019

Showing posts from category environmental peacemaking.