-

Chad Briggs: Dealing With Risk and Uncertainty in Climate-Security Issues

›July 21, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffWe must do more than simply take our current understanding of climate-change risk and extrapolate it into the future, asserted Chad Briggs of the Berlin-based Adelphi Research in a video interview with the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program.

-

Local Case Studies of Population-Environment Connections

›“The role of intergenerational transfers, land, and education in fertility transition in rural Kenya: the case of Nyeri district” in Population & Environment by Karina M. Shreffler and F. Nii-Amoo Dodoo, explores the reasons for a dramatic and unexpected decline in fertility in rural Kenya. In one province, total fertility rate (TFR) declined from 8.4 to 3.7, from 1978 to 1998. The study found numerous contributing factors for this decline, which occurred more quickly and earlier than demographers expected, but land productivity seemed to be the primary motivator. A growing population and the tradition of dividing family land among sons made continuing to have large families unrealistic for these Kenyan families. “Family planning is, therefore, not the primary causal explanation for limiting the number of children, but rather serves to help families attain their ideal family sizes,” the authors conclude. Also in Population & Environment, “Impacts of population change on vulnerability and the capacity to adapt to climate change and variability: a typology based on lessons from ‘a hard country,’” by Robert McLeman, explores the potential for human communities to adapt to climate change. The article centers on a region in Ontario that is experiencing changes in both local climatic conditions and demographics. The study finds that demographic change can have both an adverse and positive effect on the ability of a community to successfully adapt to climate change and highlights the importance of social networks and social capital to a community’s resilience or vulnerability. McLeman also presents a new typology that he hopes will “serve the purpose of drawing greater attention to the degree to which adaptive capacity is responsive to population and demographic change.”

Also in Population & Environment, “Impacts of population change on vulnerability and the capacity to adapt to climate change and variability: a typology based on lessons from ‘a hard country,’” by Robert McLeman, explores the potential for human communities to adapt to climate change. The article centers on a region in Ontario that is experiencing changes in both local climatic conditions and demographics. The study finds that demographic change can have both an adverse and positive effect on the ability of a community to successfully adapt to climate change and highlights the importance of social networks and social capital to a community’s resilience or vulnerability. McLeman also presents a new typology that he hopes will “serve the purpose of drawing greater attention to the degree to which adaptive capacity is responsive to population and demographic change.”

SpringerLink offers free access to both these articles through August 15. -

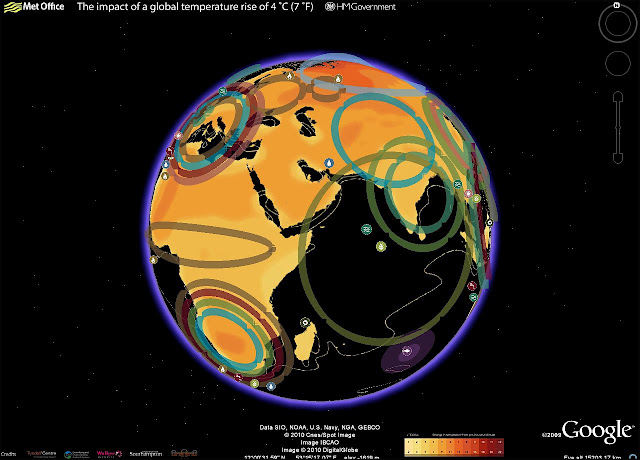

Rear Admiral Morisetti Launches the UK’s “4 Degree Map” on Google Earth

›Having had such success with the original “4 Degree Map” that the United Kingdom launched last October, my colleagues in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office have been working on a Google Earth version, which users can now download from the Foreign Office website.

This interactive map shows some of the possible impacts of a global temperature rise of 4 degrees Celsius (7° F). It underlines why the UK government and other countries believe we must keep global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial times; beyond that, the impacts will be increasingly disruptive to our global prosperity and security.

In my role as the UK’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy I have spoken to many colleagues in the international defense and security community about the threat climate change poses to our security. We need to understand how the impacts, as described in this map, will interact with other drivers of instability and global trends. Once we have this understanding we can then plan what needs to be done to mitigate the risks.

The map includes videos from the contributing scientists, who are led by the Met Office Hadley Centre. For example, if you click on the impact icon showing an increase in extreme weather events in the Gulf of Mexico region, up pops a video clip of the contributing scientist Dr Joanne Camp, talking about her research. It also includes examples of what the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and British Council are doing to increase people’s awareness of the risks climate change poses to our national security and prosperity, thus illustrating the FCO’s ongoing work on climate change and the low-carbon transition.

Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti is the United Kingdom’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy. -

India’s Maoists: South Asia’s “Other” Insurgency

›July 7, 2010 // By Schuyler Null

The Indian government’s battle with Maoist and tribal rebels – which affects 22 of India’s 35 states and territories, according to Foreign Policy and in 2009 killed more people than any year since 1971 – has been largely ignored in the West. That should change, as South Asia’s “other” insurgency, fomenting in the world’s largest democracy and a key U.S. partner, offers valuable lessons about the role of resource management and stable development in preventing conflict.

-

U.S. Navy Task Force on Implications of Climate Change

›What about climate change will impact us? That’s the question the Navy’s Task Force Climate Change is trying to answer. Rear Admiral David Titley explains the task force’s objectives in this interview by the American Geophysical Union (AGU) at their recent “Climate Change and National Security” event on the Hill.

The task force is part of the military’s recent efforts to try to better understand what climate change will mean for the armed forces, from rising sea levels and ocean acidification to changing precipitation patterns. In the interview, Admiral Titley points out that for the Navy in particular, it is important to understand and anticipate what changes may occur since so many affect the maritime environment.

The Navy’s biggest near-term concern is the Arctic, where Admiral Titley says they expect to face significant periods of almost completely open ocean during the next two to three decades. “That has huge implications,” says Titley, “since as we all know the Arctic is in fact an ocean and we are the United States Navy. So that will be an ocean that we will be called upon to be present in that right now we’re not.”

Longer term, the admiral points to resource scarcity and access issues and sea level rise (potentially 1-2 meters) as the most important contributing factors to instability, particularly in places like Asia, where even small changes can have huge impacts on the stability of certain countries. The sum of these parts plus population growth, an intersection we examine here at The New Security Beat, is something that deserves more attention, according to Titley. “The combination of climate, water, demographics, natural resources – the interplay of all those – I think needs to be looked at,” he says.

Check out the AGU site for more information, including an interview with Jeffrey Mazo – whose book Climate Conflict we recently reviewed – discussing climate change winners and losers and the developing world (hint: the developing world are the losers).

Sources: American Geophysical Union, New York Times.

Video Credit: “What does Climate Change mean for the US Navy?” courtesy of YouTube user AGUvideos. -

Backdraft: The Conflict Potential of Climate Mitigation and Adaptation

›The European Union’s biofuel goal for 2020 “is a good example of setting a target…without really thinking through [the] secondary, third, or fourth order consequences,” said Alexander Carius, co-founder and managing director of Adelphi Research and Adelphi Consult. While the 2007-2008 global food crisis demonstrated that the growth of crops for fuels has “tremendous effects” in the developing world, analysis of these threats are underdeveloped and are not incorporated into climate change policies, he said. [Video Below]

-

Sustainable Development

›Are Women the Key to Sustainable Development?, by Candice Stevens and appearing in Boston University’s Sustainable Development Insights series, asks whether gender-conscious development strategies are the missing link in the three pillars–social, economic, and environmental–of sustainable development. She points out that “An increasing number of studies indicate that gender inequalities are extracting high economic costs and leading to social inequities and environmental degradation around the world.” In the policy world gender-conscious initiatives are often more effective as well. “United Nations and World Bank studies show that focusing on women in development assistance and poverty reduction strategies leads to faster economic growth than ‘gender neutral’ approaches.” Stevens finds that achieving greater gender parity may be the key to better governance, increased growth, and a safer environment. The Role of Cities in Sustainable Development, by David Satherwaite and also appearing in Boston University’s Sustainable Development Insights series, argues that traditional depictions of cities as dirty and unsustainable are inaccurate. Instead, “…with the right innovation and incentives in place, cities can allow high living standards to be combined with resource consumption that is much lower than the norm in most cities today,” he finds. Satherwaite contends that high-density living arrangements can reduce per capita energy consumption, transportation emissions, and costs of public service provisions like hospitals and schools. However, he warns that none of these potential advantages are guaranteed, and city planners must utilize effective local governance in order to make cities safe, clean, and sustainable.

The Role of Cities in Sustainable Development, by David Satherwaite and also appearing in Boston University’s Sustainable Development Insights series, argues that traditional depictions of cities as dirty and unsustainable are inaccurate. Instead, “…with the right innovation and incentives in place, cities can allow high living standards to be combined with resource consumption that is much lower than the norm in most cities today,” he finds. Satherwaite contends that high-density living arrangements can reduce per capita energy consumption, transportation emissions, and costs of public service provisions like hospitals and schools. However, he warns that none of these potential advantages are guaranteed, and city planners must utilize effective local governance in order to make cities safe, clean, and sustainable. -

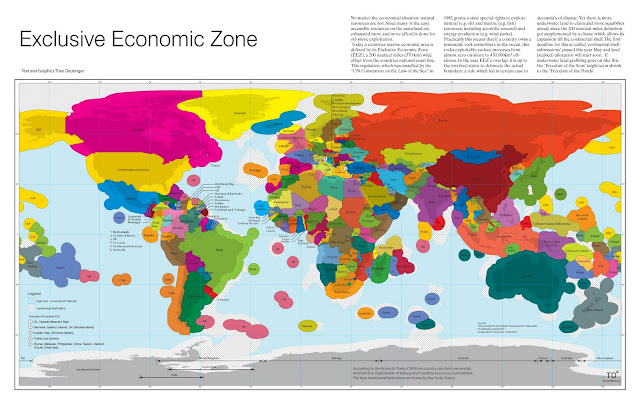

Natural Resource Frontiers at Sea

›As burgeoning populations and growing economies strain natural resource stocks around the world, countries have begun looking to more remote and difficult-to-access resources, including deep-sea oil, gas, and minerals. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) guarantees exclusive access to these resources within 200 nautical miles of a nation’s sovereign territory – called an exclusive economic zone (EEZ). TD Architects’ “Exclusive Economic Zone” illustrates this invisible global chessboard and highlights some examples of disputed areas, such as the South China Sea, the Mediterranean, the Falkland/Malvina Islands, and the Arctic.

Showing posts from category environment.