-

Climate-Security Linkages Lost in Translation

›A recent news story summarizing some interesting research by Halvard Buhaug carried the headline “Civil war in Africa has no link to climate change.” This is unfortunate because there’s nothing in Buhaug’s results, which were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, to support that conclusion.

In fact, the possibility that climate change might trigger conflict remains very real. Understanding why the headline writers got it wrong will help us better meet the growing demand for usable information about climate-conflict linkages.

First, the headline writer made a simple mistake by translating Buhaug’s modest model results — that under certain specifications climate variables were not statistically significant — into a much stronger causal conclusion: that climate is unrelated to conflict. A more responsible summary is that the historical relationship between climate and conflict depends on how the model is specified. But this is harder to squeeze into a headline — and much less likely to lure distracted online readers.

Buhaug tests 11 different models, but none of the 11 corresponds to what I would consider the emerging view on how climate shapes conflict. Using Miguel et al. (2004) as a reasonable representation of this view, and supported by other studies, there seems to be a strong likelihood that climatic shocks — due to their negative impacts on livelihoods — increase the likelihood that high-intensity civil wars will break out. None of Buhaug’s 11 models tested that view precisely.

If we are going to make progress as a community, we need to be specific about theoretically informed causal mechanisms. Our case studies and statistical tests should promote comparable results, around a discrete number of relevant mechanisms.

Second, a more profound confusion reflected in the headline concerns the term “climate change.” Buhaug’s research did not look at climate change at all, but rather historical climate variability. Variability of past climate is surely relevant to understanding the possible impacts of climate change, but there’s no way that, by itself, it can answer the question headline writers and policymakers want answered: Will climate change spark more conflict? For that we need to engage in a much richer combination of scenario analysis and model testing than we have done so far.

We are in a period in which climate change assessments have become highly politicized and climate politics are enormously contentious. The post-Copenhagen agenda for coming to grips with mitigation and adaptation remains primitive and unclear. Under these circumstances, we need to work extra hard to make sure that our research adds clarity and does not fan the flames of confusion. Buhaug’s paper is a good model in this regard, but the media coverage does not reflect its complexity. (Editor’s note: A few outlets – Nature, and TIME’s Ecocentric blog – did compare the clashing conclusions of Buhaug’s work and an earlier PNAS paper by Marshall Burke.)

The stakes are high. This isn’t a “normal” case of having trouble translating nuanced science into accessible news coverage. There is a gigantic disinformation machine with a well-funded cadre of “confusionistas” actively distorting and misrepresenting climate science. Scientists need to make it harder for them to succeed, not easier.

Here’s how I would characterize what we know and we are trying to learn:1) Economic deprivation almost certainly heightens the risk of internal war.

To understand how climate change might affect future conflict, we need to know much more. We need to understand how changing climate patterns interact with year-to-year variability to affect deprivation and shocks. We need to construct plausible socioeconomic scenarios of change to enable us to explore how the dynamics of climate, economics, demography, and politics will interact and unfold to shape conflict risk.

2) Economic shocks, as a form of deprivation, almost certainly heighten the risk of internal war.

3) Sharp declines in rainfall, compared to average, almost certainly generate economic shocks and deprivation.

4) Therefore, we are almost certain that sharp declines in rainfall raise the risk of internal war.

The same scenarios that generate future climate change also typically assume high levels of economic growth in Africa and other developing regions. If development is consistent with these projections, the risk of conflict will lessen over time as economies develop and democratic institutions spread.

To say something credible about climate change and conflict, we need to be able to articulate future pathways of economics and politics, because we know these will have a major impact on conflict in addition to climate change. Since we currently lack this ability, we must build it.Marc Levy is deputy director of the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), a research and data center of the Earth Institute of Columbia University.

Photo Credit: “KE139S11 World Bank” courtesy of flickr user World Bank Photo Collection.

-

New World Bank Report on Land Grabs Is a Dud

›After months of delays and false starts, and a tantalizing partial leak to the Financial Times earlier this summer, the much-ballyhooed World Bank report on large-scale land acquisitions has finally arrived.

-

The Complexities of Decarbonizing China’s Power Sector

›August 27, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffOver the past year, there have been a series of new initiatives on U.S.-China energy cooperation. These initiatives have focused primarily on low-carbon development, and have covered everything from renewables and energy efficiency to clean vehicles and carbon capture and storage. Central to the long-term success of these efforts will be strengthening the U.S.’s incomplete understanding of China’s electricity grid, as all of the above issues are inextricably linked to the power grid itself.

As both the United States and China try to figure out how to decarbonize their power sectors with a mixture of policy reform and infrastructure development, China’s power-sector reforms could present valuable lessons for the United States. At a China Environment Forum meeting earlier this summer, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Chairman Jon Wellinghoff joined power sector experts Jim Williams, Fritz Kahrl, and Ding Jianhua from Energy and Environmental Economics (E3) to address the subject, discussing gaps related to electricity sector analysis and presenting research on decarbonizing China’s electricity sector.

Addressing Shared Challenges

Chairman Wellinghoff kicked off the presentation with an overview of the similarities and differences in the U.S. and Chinese power sectors. Wellinghoff stressed that both countries face common obstacles in expanding renewables, namely that wind- and solar-energy sources are located inland, far away from booming coastal cities where energy demand is highest. He added that market and regulatory incentives to integrate renewables into grids are currently insufficient.

However, Wellinghoff also made the point that each side has comparative advantages. For instance, while China has superior high-voltage grid transmission technologies, the United States has been developing advanced demand-side management practices and markets to spur energy efficiency and renewable integration in the power sector. Wellinghoff argued that mutual understanding of each others’ power sectors is important for trust-building and effective cooperation, and can result in net climate and economic benefits for both sides.

Achieving these benefits will not be easy. E3’s Jim Williams noted that the Chinese power sector is currently in transition, a process that is producing some increasingly complicated policy questions. How these questions are answered has the potential to drastically shift the outlook for China’s carbon emissions. For instance, if the United States can help push China’s power sector to become less carbon-intensive, there could be substantial benefits for lowering global greenhouse gas emissions.

One of the major issues at the moment is assessing the cost-benefit analysis of renewable and low-carbon integration and trying to ascertain what the actual cost of decarbonizing the power sector would be. Due to a lack of “soft technology” — analytical methods, software models, institutional processes, and the like — policymakers in China still do not have a good sense of what level of greenhouse gas reductions could be achieved in the power sector for a given cost.

More Intensive Research Needed

Fritz Kahrl and Ding Jianhua, also from E3, went on to explain that for China, as with the United States, the underlying issues of how to decarbonize the power sector will demand considerable quantitative analysis. The United States has more than three decades of experience with quantitative policy analysis in the power sector, driven in large part by regulatory processes that require cost-benefit analysis. In China, policy analysis in the power sector is still at an early stage, but there is an increasing demand among policymakers for this kind of information.

For instance, over the past five years, China’s government has allocated significant amounts of money and attention to energy efficiency. However, standardized tools to assess the benefits and costs of energy efficiency projects are not widely used in China, which has led to a lack of transparency and accountability in how energy efficiency funds are spent. This problem is increasingly recognized by senior-level decision-makers. Drawing from its own experience, the United States could play an important role in helping Chinese analysts develop quantitative approaches for power sector policy analysis.

Pete Marsters is project assistant with the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: “Coal Power Plant (China),” courtesy of flickr user ishmatt. -

“All Consuming:” U of M’s ‘Momentum’ on Population, Health, Environment, and More

›August 23, 2010 // By Schuyler NullMinnesota’s Institute on the Environment is only in its third year of operation but has already established itself as an emerging forum for population, health, and, environment issues, due in no small part to its excellent thrice-a-year publication, Momentum. The journal is not only chock-full of high production values and impressively nuanced stories on today’s global problems, but is also, amazingly, available for free.

Momentum has so far covered issues ranging from food security, gender equity, demographic change, geoengineering, climate change, life without oil, and sustainable development.

Highlights from the latest issue include: “Girl Empower,” by Emily Sohn; “Bomb Squad,” with Paul Ehrlich, Bjørn Lomborg, and Hans Rosling; and “Population Hero,” on the fiscal realities of stabilizing growth rates.

The lead story featured below, “All Consuming,” by David Biello, focuses on the debate over whether consumption or population growth poses a bigger threat to global sustainability.Two German Shepherds kept as pets in Europe or the U.S. use more resources in a year than the average person living in Bangladesh. The world’s richest 500 million people produce half of global carbon dioxide emissions, while the poorest 3 billion emit just 7 percent. Industrial tree-cutting is now responsible for the majority of the 13 million hectares of forest lost to fire or the blade each year — surpassing the smaller-scale footprints of subsistence farmers who leave behind long, narrow swaths of cleared land, so-called “fish bones.”

Continue reading on Momentum.

In fact, urban population growth and agricultural exports drive deforestation more than overall population growth, according to new research from geographer Ruth DeFries of Columbia University and her colleagues. In other words, the increasing urbanization of the developing world — as well as an ongoing increase in consumption in the developed world for products that have an impact on forests, whether furniture, shoe leather, or chicken fed on soy meal — is driving deforestation, rather than containing it as populations leave rural areas to concentrate in booming megalopolises.

So are the world’s environmental ills really a result of the burgeoning number of humans on the planet — growing by more than 150 people a minute and predicted by the United Nations to reach at least 9 billion people by 2050? Or are they more due to the fact that, while human population doubled in the past 50 years, we increased our use of resources fourfold?

Photo Credit: “All Consuming” courtesy of Momentum. -

Fire in the Hole: A Look Inside India’s Hidden Resource War

›August 18, 2010 // By Schuyler Null -

How Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Impact Economic Development

›“Investing in women and girls is the right thing to do,” says Mayra Buvinic, sector director of the World Bank’s gender and development group. “It is not only fair for gender equality, but it is smart economics.” But while it may be smart economics, many developing countries fail to address the underlying social causes that impact economic growth, such as poverty and gender inequality. Buvinic was joined by Dr. Nomonde Xundu, health attaché at the Embassy of South Africa in Washington, D.C., and Mary Ellen Stanton, senior maternal health advisor at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), at the sixth meeting of the Advancing Policy Dialogue on Maternal Health Series, which addressed the economic impact of maternal mortality and provided evidence for the need for increased investment in maternal health.

-

Reform Aid to Pakistan’s Health Sector, Says Former Wilson Center Scholar

›August 5, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffExcerpt from op-ed by Samia Altaf and Anjum Altaf in Dawn:

WE must state at the outset that we have been wary of, if not actually opposed to, the prospect of further economic assistance to Pakistan because of the callous misuse and abuse of aid that has marked the past across all elected and non-elected regimes.

We are convinced that such aid, driven by political imperatives and deliberately blind to the well-recognised holes in the system, has been a disservice to the Pakistani people by destroying all incentives for self-reliance, good governance and accountability to either the ultimate donors or recipients.

Even without the holes in the system the kind of aid flows being proposed are likely to prove problematic. Over half a century ago, Jane Jacobs, in a brilliant chapter (Gradual and Cataclysmic Money) in a brilliant book (The Death and Life of Great American Cities), showed convincingly how ‘cataclysmic’ money (money that arrives in huge amounts in short periods of time) is a surefire way of destroying all possibilities of improvement. What is needed, she argued, is ‘gradual’ money in the control of the residents themselves. While Jacobs was writing in the context of aid to impoverished communities within the US, she concluded with a remarkably prescient concern: “I hope we disburse foreign aid abroad more intelligently than we disburse it at home.”

Continue reading on Dawn.

For more on U.S. aid to Pakistan, see New Security Beat‘s coverage of the recent U.S.-Pakistani Strategic Dialogue.

Photo Credit: A U.S. Army Soldier with 32nd Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division, hands out medical supplies to Pakistani refugees outside an International Committee of the Red Crescent aid station in Afghanistan’s Kunar province, October 23, 2009. Courtesy of flickr user isafmedia. -

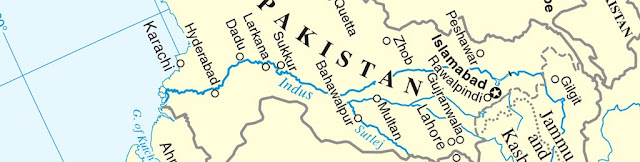

Wilson Center’s Michael Kugelman Finds the Real Culprit in Pakistan’s Water Shortage

›July 28, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffExcerpt from Dawn:

ON Jan 15, 2006, the Karachi Port Trust (KPT) inaugurated its new fountain – the Rs320m lighted harbour structure that spews seawater hundreds of feet into the air.

Also on this day – as on most others in Karachi – several million gallons of the city’s water supply were lost to leakage, some hundred million gallons of raw sewage oozed into the sea, and scores of Karachiites failed to secure clean water.

Over the next few years, the fountain jet would produce a powerful and relentless stream of water high above Karachi. Meanwhile, down below, tens of thousands of the city’s masses would die from unsafe water.

After several fountain parts were stolen in 2008, the KPT quickly made the necessary repairs and re-launched what it deems “an extravaganza of light and water”.

In an era of rampant resource shortages, boasting about such extravagance demonstrates questionable judgment. So, too, does the willingness to lavish millions of rupees on a giant water fountain, and then to repair it fast and furiously – while across Karachi and the nation as a whole, drinking water and sanitation projects are heavily underfunded and water infrastructure stagnates in disrepair.

Continue reading on Dawn.

For more on Pakistan’s water crisis, see the Wilson Center report, “Running on Empty.”

Photo Credit: Adapted from UN map of South Asia, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Showing posts from category economics.