-

Weekly Reading

›In an Economist.com debate on population growth between John Seager of Population Connection and Michael Lind of the New America Foundation, Seager argues that rapid population growth is “the source of many of the world’s—especially the poor world’s—woes,” as it accelerates environmental degradation and “undermines both security and development.” On the other hand, Lind counters that “countries are not poor because they have too many people,” and asserts that “technology and increased efficiency have refuted what looks like imminent resource exhaustion.”

In Foreign Policy, David J. Rothkopf contends that actions to mitigate climate change—though necessary to avoid very serious consequences—could subsequently spur trade wars, destabilize petro-states, and exacerbate conflict over water and newly important mineral resources (including lithium).

The International Crisis Group (ICG) reports that “the exploitation of oil has contributed greatly to the deterioration of governance in Chad and to a succession of rebellions and political crises” since construction of the World Bank-financed Chad-Cameroon pipeline was completed in 2003. Chad must reform its management of oil resources in order to avoid further impoverishment and destabilization, ICG advises.

The Royal Society and the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IME)—both based in the United Kingdom—released independent reports on geoengineering the climate. While calling reduction of greenhouse gas emissions “the safest and most predictable method of moderating climate change,” the Royal Society recommends that governments and international experts look into three techniques with the most potential: CO2 capture from ambient air, enhanced weathering, and land use and afforestation. The IME identified artificial trees, algae-coated buildings, and reflective buildings as the most promising alternatives. “Geo-engineering is no silver bullet, it just buys us time,” IME’s Tim Fox told the Guardian.

In “Securing America’s Future: Enhancing Our National Security by Reducing Oil Dependence and Environmental Damage,” the Center for American Progress (CAP) argues that unless the United States switches to other fuels, it “will become more invested in the volatile Middle East, more dependent on corrupt and unsavory regimes, and more involved with politically unstable countries. In fact, it may be forced to choose between maintaining an effective foreign policy or a consistent energy supply.”

The Chinese government is “drawing up plans to prohibit or restrict exports of rare earth metals that are produced only in China and play a vital role in cutting edge technology, from hybrid cars and catalytic converters, to superconductors, and precision-guided weapons,” The Telegraph relates. The move could send other countries scrambling to find replacement sources.

In studying the vulnerability of South Africa’s agricultural sector to climate change, the International Food Policy Research Institute finds that “the regions most vulnerable to climate change and variability also have a higher capacity to adapt to climate change…[and that] vulnerability to climate change and variability is intrinsically linked with social and economic development.” South African policymakers must “integrate adaptation measures into sustainable development strategies,” the group explains. -

Climate Change Is Linked to Security, But Don’t Overplay It

›August 31, 2009 // By Wilson Center StaffAs the impacts of climate change on national security are beginning to receive attention at the highest levels of government, climate-security experts must avoid oversimplifying these complex connections, said Geoff Dabelko, director of the Environmental Change and Security Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

“Today, with climate change high on the political agenda, powerful actors in the security community are assessing its potentially dangerous effects on conflict and military readiness,” Dabelko said. In “Planning for Climate Change: The Security Community’s Precautionary Principle” in the journal Climatic Change, Dabelko views the defense community’s interest in climate change as an understandable development. “Climate change poses threats and opportunities that any risk analysis calculation should take seriously—including the military’s planning efforts, such as the Quadrennial Defense Review,” he says.

“However, it is important to remember that in the mid-1990s, advocates oversold our understanding of environmental links to security, creating a backlash that ultimately undermined policymakers’ support for meeting the very real connections between environment and conflict head-on. Today, ‘climate security’ is in danger of becoming merely a political argument that understates the complexity of climate’s security challenges.”

In a new op-ed in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Dabelko offers some advice to scientists, politicians, and the media:- Don’t oversimplify the links between climate change and violent conflict or terrorism.

- Don’t neglect ongoing natural resource and conflict problems.

- Don’t assume we know the precise scale and location of climate-induced migration.

- Don’t forget that climate mitigation efforts can introduce social conflict and needs to be factored into both mitigation and adaptation efforts.

-

Weekly Reading

›Christian Aid’s “Growing Pains: The Possibilities and Problems of Biofuels” finds that “huge subsidies and targets in developed countries for boosting the production of fuels from plants such as maize and palm oil are exacerbating environmental and social problems in poor nations.”

Framing the climate change debate in terms of national security could help advance climate legislation in Congress, argues a New York Times editorial, one week after its front-page article on the topic. In letters to the editor, James Morin of Operation FREE calls climate change the “ultimate destabilizer,” and retired Vice Admiral Lee Gunn warned that the “repercussions of these changes are not as far off as one would think.”

Researchers at Purdue University’s Climate Change Research Center found that climate change could deepen poverty, especially in urban areas of developing countries, by increasing food prices. “While those who work in agriculture would have some benefit from higher grains prices, the urban poor would only get the negative effects.” Of the 16 countries studied, “Bangladesh, Mexico and Zambia showed the greatest percentage of the population entering poverty in the wake of extreme drought.”

India’s 2009 State of the Environment Report finds that almost half of the country’s land is environmentally degraded, air pollution is increasing, and biodiversity is decreasing. In addition, the report points out that almost 700 million rural people—more than half the country’s population—are directly dependent on climate-sensitive resources for their subsistence and livelihoods. And furthermore, “the adaptive capacity of dry land farmers, forest dwellers, fisher folk and nomadic shepherds is very low.”

Surveys completed by a Cambodian national indigenous peoples network find that “five million hectares of land belonging to indigenous minority peoples [have] been appropriated for mining and agricultural land concessions in the past five years,” reports the Phnom Penh Post.

The Economic Report on Africa 2009 warns that despite declining food prices, “many African countries continue to suffer from food shortage and food insecurity due to drought, conflicts and rigid supply conditions among other factors.” -

Budgeting for Climate

› Update: Read a response by Miriam Pemberton

Update: Read a response by Miriam Pemberton“The Obama administration…has identified the task of substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions as one of its top priorities,” writes Miriam Pemberton in a new report from the Institute for Policy Studies, “Military vs. Climate Security: Mapping the Shift from the Bush Years to the Obama Era.”

-

Demography and Democracy in Iran

›August 12, 2009 // By Brian Klein President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad might have blamed sinister “foreign powers” for fomenting post-election civil unrest in Iran, but some analysts have fingered another culprit: demography. According to Farzaneh (Nazy) Roudi, program director for the Middle East and North Africa at the Population Reference Bureau, two phenomena “provide a backdrop for understanding Iran’s current instability.” First is the country’s youthful population age structure, or “youth bulge”; over 30 percent of Iranians are between the ages of 15 and 29, and 60 percent are under the age of 30. Second is Iran’s surprisingly comprehensive family planning program, which has empowered women to make their own reproductive choices and enter higher education en masse.

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad might have blamed sinister “foreign powers” for fomenting post-election civil unrest in Iran, but some analysts have fingered another culprit: demography. According to Farzaneh (Nazy) Roudi, program director for the Middle East and North Africa at the Population Reference Bureau, two phenomena “provide a backdrop for understanding Iran’s current instability.” First is the country’s youthful population age structure, or “youth bulge”; over 30 percent of Iranians are between the ages of 15 and 29, and 60 percent are under the age of 30. Second is Iran’s surprisingly comprehensive family planning program, which has empowered women to make their own reproductive choices and enter higher education en masse. -

Going Back to Cali–or Chennai: Cities Should Plan For “Climate Migration”

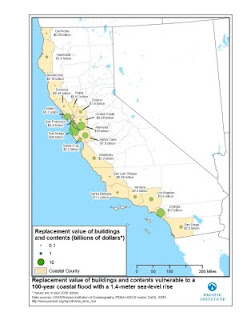

›August 6, 2009 // By Elizabeth Hipple On Monday, California became the first U.S. state to issue a report outlining strategies for adapting to climate change. Among other recommendations, it suggests that Californians should consider moving.

On Monday, California became the first U.S. state to issue a report outlining strategies for adapting to climate change. Among other recommendations, it suggests that Californians should consider moving. -

Senate, Pentagon Focus on Climate-Security Challenges

›July 31, 2009 // By Brian Klein “Climate change may well be a predominant national security challenge of the 21st century, posing a range of threats to U.S. and international security,” said Sharon Burke, vice president for Natural Security at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS). Her remarks at a July 21 Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on climate change and security—along with those of two retired vice admirals and former Senator John Warner—amplified the growing chorus of national security experts and military personnel urging Congress to act promptly to address the security implications of climate change.

“Climate change may well be a predominant national security challenge of the 21st century, posing a range of threats to U.S. and international security,” said Sharon Burke, vice president for Natural Security at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS). Her remarks at a July 21 Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on climate change and security—along with those of two retired vice admirals and former Senator John Warner—amplified the growing chorus of national security experts and military personnel urging Congress to act promptly to address the security implications of climate change.

Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, USN (Ret.), called climate change “a clear and present danger to the United States of America,” while Burke cited a 2007 report from the Center for Naval Analysis that defined climate change as a “threat multiplier.”

Security Link Could Push Senate Climate Bill

Senator John Kerry, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, scheduled last week’s hearing on climate’s security links in a bid to bolster support for congressional action on climate change, which is currently stalled in the Senate. “Just as 9/11 taught us the painful lesson that oceans could not protect us from terror, today we are deluding ourselves if we believe that climate change will stop at our borders,” he said.

Former Senator John Warner echoed this sentiment, noting that the hearing was an opportunity to “educate the American public on these potential risks to our national security posed by global climate change.”

“Leading military, intelligence, and security experts have publically spoken out that if left unchecked, global warming could increase instability and lead to conflict in already fragile regions of the world. If we ignore these facts, we do so at the peril of our national security and increase the risk to those in uniform who serve our nation,” stated Warner, who recently launched the Pew Project on National Security, Energy, and Climate with the Pew Environment Group.

Pentagon Looks to Reduce Reliance on Oil and Drive Innovation

Burke explained that the phenomenon will not only pose “direct threats to the lives and property of Americans” from wildfires, droughts, flooding, severe storms, the spread of diseases, and mass migrations, but will also have “direct effects on the military,” including problems with infrastructure and the supply chain.

As a massive consumer of energy—110 million barrels of oil and 3.8 billion kilowatts of electricity in 2006 alone—the Pentagon has recognized its vulnerability to disruptions in fossil fuel supplies, as well as its potential to develop alternative technologies. As ClimateWire’s Jessica Leber writes in the New York Times: “The long logistics ‘tail’ that follows troops into the war zone—moving fuel, water and supplies in and waste out—risks lives and diverts major resources from fighting.”

According to Leber, two-thirds of the tonnage in Iraq convoys was fuel and water. To mitigate such vulnerability in the future—not to mention in arid, mountainous Afghanistan—DoD has begun testing ways to turn waste into energy, distribute power through “microgrids,” develop jet fuel from algae, desalinate water using little energy, and purify wastewater on a small scale.

“While the military by itself won’t make a market for plug-in vehicles or algae-based jet fuel,” notes Leber in an earlier ClimateWire article, “its investment power can bump emerging climate-friendly technologies onto a larger commercial stage.”

At the hearing, Burke warned against the possible knock-on effects of switching dependence from fossil fuel to other resources like lithium for lithium-ion batteries in electric cars.

The Military Must Manage Uncertainty

Vice Admiral Dennis McGinn, USN (Ret.), a member of the CNA’s Military Advisory Board, dismissed the argument that climate data and projections are too uncertain to form a solid basis for action. “As military professionals,” he told the Senate committee, “we were trained to make decisions in situations defined by ambiguous information and little concrete knowledge of the enemy intent. We based our decisions on trends, experience, and judgment, because waiting for 100% certainty during a crisis can be disastrous, especially one with the huge national security consequences of climate change.”

“The future has a way of humbling those who try to predict it too precisely,” Kerry said at the hearing. “But we do know, from scientists and security experts, that the threat is very real. If we fail to connect the dots—if we fail to take action—the simple, indisputable reality is that we will find ourselves living not only in a ravaged environment, but also in a more dangerous world.”

Photo: A convoy of the U.S. Army’s 515th Transportation Division moves fuel around Baghdad, Iraq. Courtesy Flickr user heraldpost. -

Weekly Reading

›“The natural resources are being depleted at an alarming rate, as population pressures mount in the Arab countries,” says the 2009 Arab Human Development Report, which was published this week by the UN Development Programme. A launch event in Washington, DC, features New York Times columnist Tom Friedman and Wilson Center scholar Robin Wright.

A special issue of IHDP Update focuses on “Human Security in an Era of Global Change,” a synthesis report tied to the recent GECHS conference. Articles by GECHS members, including Karen O’Brien and Alexander Lopez, address water and sanitation, the global financial crisis, poverty, and transborder environmental governance in Latin America.

An op-ed by Stanley Weiss in the New York Times argues that the best way to bring water–and peace–to the Middle East is to ship it from Turkey. A response by Gabriel Eckstein in the International Water Law Project blog argues that “transporting water from Turkey to where it is needed will require negotiations of Herculean proportion.”

CoCooN, a new international program sponsored by The Netherlands on conflict and cooperation over natural resources, recently posted two powerpoint presentations explaining its goals and the matchmaking workshops it will hold in Addis Ababa, Bogota, and Hanoi. The deadline for applications is August 5.

Two new IFPRI research papers focus on the consequences of climate change for poor farmers in Africa and provide policymakers with adaptation strategies. “Economywide Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa” analyzes two possible options for the region. “Soil and Water Conservation Technologies: A Buffer Against Production Risk in the Face of Climate Change?” investigates the impact of different soil and water conservation technologies on the variance of crop production in Ethiopia.

Showing posts from category conflict.

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad might have blamed sinister “

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad might have blamed sinister “ On Monday, California became the first U.S. state to issue a

On Monday, California became the first U.S. state to issue a  “Climate change may well be a predominant national security challenge of the 21st century, posing a range of threats to U.S. and international security,” said

“Climate change may well be a predominant national security challenge of the 21st century, posing a range of threats to U.S. and international security,” said