Showing posts from category Africa.

-

International River Basins: Mapping Institutional Resilience to Climate Change

›Institutions that manage river basins must assess their ability to deal with variable water supplies now, said Professor Aaron Wolf of Oregon State University at the July 28 ECSP event, “International River Basins: Mapping Institutional Resilience to Change.” “A lot of the world currently can’t deal with the variability that they have today, and we see climate change as an exacerbation to an already bad situation.”

Wolf and his colleagues, Jim Duncan of the World Bank and Matt Zentner of the U.S. Department of Defense, discussed their efforts to map basins at risk for future tensions over water, as identified in their coauthored World Bank report, “Mapping the Resilience of International River Basins to Future Climate Change-Induced Water Variability.” [Video Below]

Floating Past the Rhetoric of “Water Wars”

Currently, there are 276 transnational water basins that cross the boundaries of two or more countries, said Wolf. “Forty percent of the world’s population lives within these waters, and interestingly, 80 percent of the world’s fresh water originates in basins that go through more than one country,” he said. Some of these boundaries are not particularly friendly – those along the Jordan and Indus Rivers, for example – but “to manage the water efficiently, we need to do it cooperatively,” he said.

Wolf and his colleagues found that most of the rhetoric about “water wars” was merely anecdotal, so they systematically documented how countries sharing river basins actually interact in their Basins at Risk project. The findings were surprising and counterintuitive: “Regularly we see that at any scale, two-thirds of the time we do anything over water, it is cooperative,” and actual violent conflict is extremely rare, said Wolf.

Additionally, the regions where they expected to see the most conflict – such as arid areas – were surprisingly the most cooperative. “Aridity leads to institutions to help manage aridity,” Wolf said. “You don’t need cooperation in a humid climate.”

“It’s not just about change in a basin, it’s about the relationship between change and the institutions that are developed to mitigate the impacts of change,” said Wolf. “The likelihood of conflict goes up when the rate of change in a basin exceeds the institutional capacity to absorb the change.”

Expanding the Database for Risk Assessment

Oregon State University’s Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) tracks tabular and spatial information on more than 680 freshwater treaties along 276 transboundary river basins, said Jim Duncan. The team expanded the database to include recent findings on variability, as well as the impacts of climate change on the future variability of those basins. “We have a lot more information that we are able to work with now,” Duncan said.

Analyzing the institutional vulnerability of treaties along with hydrological hazards, they found the risk of tension concentrated in African basins: The Niger, Congo, and Lake Chad basins “popped out,” said Duncan. When predicting future challenges, they found that basins in other areas, such as Southeastern Asia and Central Europe, would also be at risk.

Duncan and his colleagues were able to identify very nuanced deficiencies in institutional resilience. “Over half of the treaties that have ever been signed deal with variability only in terms of flood control, and we’re only seeing about 15 percent that deal with dry season control,” said Duncan. “It’s not the actual variability, but the magnitude of departure from what they’re experiencing now that is going to be really critical.”

Beyond Scarcity

“Generally speaking, it’s not really the water so much that people are willing to fight over, but it’s the issues associated with water that cause people to have disagreements,” said Matt Zentner. Water issues are not high on the national security agendas of most governments; they only link water to national security when it actively affects other sectors of society, such as economic growth, food availability, and electric power, he said. Agricultural production – the world’s largest consumer of water – will be a major concern for governments in the future, he said, especially in developing countries economically dependent on farming.

Some experts think that current international treaties are not enough, said Zentner. Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute has said that “the existing agreements and international principles for sharing water will not adequately handle the strain of future pressures, particularly those caused by climate change.”

How transboundary water treaties fare as the climate and consumption rates change is not as simple as measuring flow; the strength of governing institutions, the parties involved, and other variables all play major roles as well, said Zentner. “When you have flexibility built within [a treaty], it allows it to be a living, breathing, and important part of solving those [water] problems.”

Download the full event transcript here.

Sources: Oregon State University, Pacific Institute.

Photo Credit: “Confluence of the Zanskar and Indus,” courtesy of Flickr user Sanish Suresh. -

Conflict Minerals in the DRC: Still Fighting Over the Dodd-Frank Act, One Year Later

›August 11, 2011 // By Schuyler Null

One year after the Dodd-Frank Act passed Congress with a provision that was aimed at preventing the sourcing of “conflict minerals” by SEC-registered companies, backlash seems to be growing over the impact of the measure, particularly on artisanal miners in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

-

Environmental Cooperation for Peacebuilding in Sierra Leone

›Sierra Leone’s decade-long civil war led to a complete collapse of environmental management in the country, according to Oli Brown, an environmental affairs officer with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). Speaking at the Wilson Center last month, Brown highlighted the country’s current environmental conditions and how they have evolved since the war ended in 2002, while also outlining UNEP’s support for rebuilding the country’s natural resource governance.

Despite its wealth of natural resources, Sierra Leone is plagued by high unemployment, a massive gap between the poor and wealthy, and extreme poverty – 70 percent of the population lives on $1.00 a day. The country is still “very fragile,” said Brown; the poor distribution of resources is partly responsible for the current problems facing the country.

Sierra Leone’s environmental future and prospects for improving its natural resource governance depend on the answers to three key questions, said Brown:

The first 5 to 10 years after a civil war are a critical time for peacebuilding efforts, Brown emphasized. Natural resources can help in this peace building process, but countries must recognize the value of their natural resources, and establish policies that are sustainable – environmentally, economically, and socially.- How can the countries bountiful natural resources be shared more equitably?

- How can the countries natural resources improve local livelihoods and provide jobs?

- How can the war’s legacies be properly addressed while minimizing their negative impact?

Potential in Abundance: Agriculture, Minerals, Fisheries, and Tourism

Today, agriculture – including rice, palm oil, and sugar cane – accounts for 50 percent of Sierra Leone’s GDP, but current production methods are extremely inefficient, said Brown. Farmers use slash-and-burn clearing techniques to grow crops with zero consideration for the environmental effects, a practice which has led to a high level of deforestation. Only four percent of the country’s original forest cover remains, he said.

As part of its plan, Sierra Leone’s government is actively seeking large-scale investment in agricultural products for export. However, access to land development is complicated by the fact that more than 100 different chiefs control land and leasing rights around the country.

Additionally, some fear that companies investing in Sierra Leone may be exploiting the situation to achieve maximum profit without providing local development benefits, such as employment.

Water is also crucial to agriculture development, but Sierra Leone’s government does not know how much they have, said Brown, so they cannot properly plan for addressing the needs of their people. Reforming the sector is critical, as palm oil and sugar cane in particular have great potential for increasing the country’s GDP.

Sierra Leone also has an abundant supply of minerals: Diamonds, iron, rutile, gold, and oil currently account for about 20 percent of GDP and approximately 250,000 jobs, said Brown.

The planned Tonkolili iron mine will be the largest of its type built over the past 20 years anywhere in the world. If successful, the mine could double Sierra Leone’s GDP, he said. But the government must monitor these mining operations to ensure that the environmental damage does not undermine the economic benefits, said Brown. For example, rutile mining without proper safety precautions has produced acid lakes, he said, some of which have been measure with a PH level of 3.7 or greater.

While fishing operations in Sierra Leone make up only 10 percent of GDP, fish provide 80 percent of the animal protein consumed in the country’s households. However, lack of regulation and enforcement has left the door open for rampant illegal and unregulated fishing, said Brown, which has depleted local fish stocks and reduced the size of fish that are caught threatening the country’s food security.

On a more positive note, environmental tourism could be a potential source of sustainable revenue. The large chimpanzee population and the national parks could be strong tourist draws. However, the country must overcome its “blood diamonds” stigma in order to take advantage of its potential.

UNEP is seeking to help Sierra Leone’s government develop its environmental regulations and planning, said Brown, such as ways to measure and regulate water usage. The regulation of agriculture, minerals, fisheries, and tourism industries will be vital steps toward helping Sierra Leone build a sustainable economy and a sustainable peace.

Sources: Awoko Newspaper, Delegation of the European Union to Sierra Leone, Infinity Business Media, The Oakland Institute, UNDP, USAID.

Photo Credit: “mining57,” courtesy of flickr user thehunter1184. -

PRB’s Population Data Sheet 2011: The Demographic Divide

›August 9, 2011 // By Kellie Furr“Today, most population growth is concentrated in the world’s poorest countries – and within the poorest regions of those countries,” write the authors of the 2011 Population Data Sheet, an analysis tool published annually by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB). The population projections between poor and rich countries are “stark and very sad,” said Carl Haub Haub, senior demographer at PRB, at the July 28 web-based launch of the Data Sheet: “We call it the demographic divide. It shows the vast difference that has developed between the rich and poor countries of the world.”

The Population Data Sheet offers insight on global population trends using detailed statistical information along 18 demographic, population, health, and environment indicators for more than 200 countries and regions. The data sheet is based on the latest projections of the UN Population Division. Carl Haub and James Gribble of PRB discussed the long-term implications of the data sheet’s projections during web-based launch that included open questions.

Conflicting Trends

“Even though the world population growth rate has slowed from 2.1 percent per year in the late 1960s to 1.2 percent today, the size of the world’s population has continued to increase – from 5 billion in 1987, to 6 billion in 1999, and to 7 billion in 2011,” write the authors in PRB’s July Population Bulletin, “The World at 7 Billion.” To put those population totals into perspective, it took from the inception of human existence until the year 1800 – a total of approximately 50,000 years – to reach the first billion.

Fortunately, the recent (relative) decline in global growth rate has already curbed what could have been a considerable surge in the world’s population: “If the late 1960s population growth rate of 2.1 percent – the highest in history – had held steady, world population would have grown by 117 million annually, and today’s population would have been 8.6 billion,” said PRB President Wendy Baldwin in a press release. However, the world’s population still grows significantly at 77 million people annually, according to the UN, and we’re slated to reach 8 billion in just another 12 years. How can this dichotomy of large population totals in the face of lowered fertility be explained?

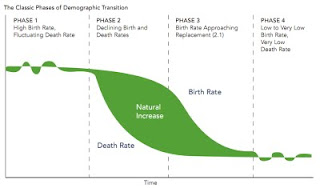

The Phases of Demographic Transition

“To understand global, we actually have to think local,” said PRB in their film short, “7 Billion and Counting,” released alongside the data sheet. Individual countries go through demographic transitions at different times, and the disparity in where countries are along in their progression varies greatly.

A demographic transition essentially hinges on two trends: the decline of birth and death rates over time. These trends do not necessarily change simultaneously however, resulting in most cases, first, a natural increase (when mortality rates decline but birth rates remain high) followed by a natural decrease in population (when birth rates also decline). Though the timing and magnitude of these trends differ from place to place, there are broad similarities across countries which have been conceptualized as phases by demographers, such as Carl Haub and James Gribble.

Phase one is characterized by high birth rates and fluctuating death rates, found in countries such as Niger, Afghanistan, and Uganda; typically only death rates decline in this phase. Phase two, encompassing mostly lower-middle income countries such as Guatemala, Ghana, and Iraq, is marked by a continued decline in death rates but only slightly lower birth rates. The potential for large population growth exists in these countries, as they still possess a large youth population.

Countries in phase three have yet lower birth and death rates and overall total fertility rates close to the widely-accepted replacement level of 2.1 children per woman; these countries are home to approximately 38 percent of the world’s population and include India, Malaysia, and South Africa. Phase three countries often still possess a disproportionately large working age population as an echo of their previous growth, which allows them to take advantage of the “demographic dividend.”

Finally, phase four countries have the lowest birth and death rates, with some even seeing negative growth as total fertility rate falls at or below the natural replacement rate; countries in this phase include most of Europe and other developed countries, such as Japan and the United States (though relatively high levels of immigration keeps overall growth higher).

The data sheet shows that most developing countries still remain in the earlier phases of demographic transition, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Relatively recent public health improvements in these countries have decreased death rates at a rapid rate, and though total fertility rates (TFR) have declined as well, they have not kept the same pace: “This lag between the drop in death rates and the drop in birth rates produced unprecedented levels of population growth,” wrote Haub and Gribble in the Population Bulletin.

A Tale of Two Worlds

The data sheet authors observe that poverty is strongly associated with countries which are stalled in their progression through the demographic transition:Poverty has emerged as a serious global issue, particularly because the most rapid population growth is occurring in the world’s poorest countries and, within many countries, in the poorest states and provinces…Relatively high population growth rates make it more difficult to lift large numbers of people out of poverty.

In her primer video on demographic security for ECSP, demographer Elizabeth Leahy Madsen said, “we are in an era of unprecedented demographic divergence,” and characterized the phenomenon of population trends moving simultaneously in different directions as “rapid” and “unprecedented.”

Haub used Italy and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as an example to illustrate the divide. Although both countries currently sit at around 60 million people each, Italy is only projected to grow by 2 million through 2050, while the DRC is projected to reach a staggering 149 million people. Italy has a gross national income per capita of about $35,000, whereas DRC has only $180 per capita, according to the World Bank.

This observation has been corroborated by other demographers: “In 1950, 68 percent of the world’s population resided in developing regions. Today that’s up to 82 percent. But in the year 2050, it’s projected to be 86 percent,” said demographer David Bloom on NPR’s global health blog, Shots.

Demography ≠ Destiny

A poor country is not necessarily tethered to its projections, which are based on assumptions, said the authors, “but when, how, and whether [the demographic transition] actually happens cannot be known.”

Low development indicators do not always dictate that a country will lag in a demographic transition. “Government commitment to a policy to lower [birth rates] has succeeded quite well in countries with a low level of development,” said Haub in a 2008 PRB discussion on the demographic divide. Bangladesh and Iran are two examples of countries that significantly affected their demographic trajectories in the 20th century with targeted programs.

Proactivity certainly plays a role, as the PRB “7 Billion and Counting” video puts it (see above): “Understanding how and why the world’s population is growing will help nations better plan for the future…and for future generations.”

Sources: NPR, Population Reference Bureau, UN-DESA, UNICEF, World Bank.

Video and Image Credit: “7 Billion and Counting,” courtesy of PRB’s Youtube channel, and stages of demographic transition courtesy of PRB’s 2011 Population Data Sheet. -

Reducing Health Inequities to Better Weather Climate Change

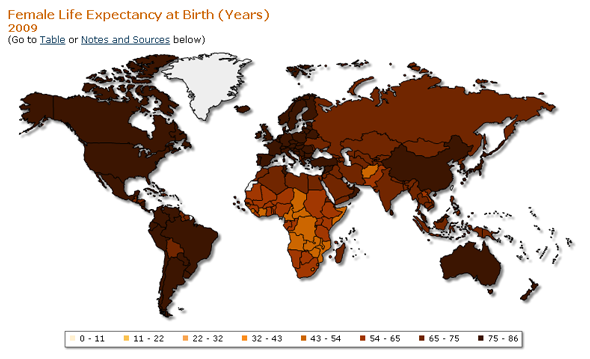

›In an article appearing in the summer issue of Global Health, Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), brings to light what she calls the starkest statistic in public health: the vast difference in the mortality rates between rich and poor countries. For example, the life expectancy of a girl is doubled if she is born in a developed country rather than in a developing country. Chan writes that efforts to improve health in developing countries now face an additional obstacle: “a climate that has begun to change.”

Climate change’s effect on health has increasingly moved into the spotlight over the past year: DARA’s Climate Vulnerability Monitor measures the toll that climate change took in 2010 on human health, estimating some 350,000 people died last year from diseases related to climate change. The majority of these deaths took place in sub-Saharan Africa, where weak health systems already struggle to deal with the disproportionate disease burden found in the region. The loss of “healthy life years” as a result of global environmental change is predicted to be 500 times greater in poor African populations than in European populations, according to The Lancet.

The majority of these deaths are due to climate change exacerbating already-prominent diseases and conditions, including malaria, diarrhea, and malnutrition. Environmental changes affect disease patterns and people’s access to food, water, sanitation, and shelter. The DARA Climate Vulnerability Monitor predicts that these effects will cause the number of deaths related to climate change to rise to 840,000 per year by 2030.

But few of these will be in developed countries. With strong health systems in place, they are not likely to feel the toll of a changing environment on their health. Reducing these inequities can only be achieved by alleviating poverty, which increases the capacity of individuals, their countries, and entire regions to adapt to climate change. It would be in all of our interests to do just this, writes Chan: “A world that is greatly out of balance is neither stable nor secure.”

Sarah Lindsay is a program assistant at the Ministerial Leadership Initiative for Global Health and a Masters candidate at American University.

Sources: DARA, Global Health, The Lancet, World Health Organization.

Image Credit: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation and the World Health Organization. -

Lakis Polycarpou, Columbia Earth Institute

The Year of Drought and Flood

›August 1, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Lakis Polycarpou, appeared on the Columbia Earth Institute’s State of the Planet blog.

On the horn of Africa, ten million people are now at risk as the region suffers the worst drought in half a century. In China, the Yangtze – the world’s third largest river – is drying up, parching farmers and threatening 40 percent of the nation’s hydropower capacity. In the U.S. drought now spreads across 14 states creating conditions that could rival the dust bowl; in Texas, the cows are so thirsty now that when they finally get water, they drink themselves to death.

And yet this apocalyptic dryness comes even as torrential springtime flooding across much of the United States flows into summer; even as half a million people are evacuated as water rises in the same drought-ridden parts of China.

It seems that this year the world is experiencing a crisis of both too little water and too much. And while these crises often occur simultaneously in different regions, they also happen in the same places as short, fierce bursts of rain punctuate long dry spells.

The Climate Connection

Most climate scientists agree that one of the likely effects of climate will be an acceleration of the global water cycle, resulting in faster evaporation and more precipitation overall. Last year, the Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences published a study which suggested that such changes may already be underway: According to the paper, annual fresh water flowing from rivers into oceans had increased by 18 percent from 1994 to 2006. It’s not hard to see how increases in precipitation could lead to greater flood risk.

At the same time, many studies make the case that much of the world will be dramatically drier in a climate-altered future, including the Mediterranean basin, much of Southwest and Southeast Asia, Latin America, the western two-thirds of the United States among other places.

Continue reading on State of the Planet.

Sources: Associated Press, The New York Times, Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences, Reuters, Science Magazine, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.

Photo Credit: “Drought in SW China,” courtesy of flickr user Bert van Dijk. -

Second Generation Biofuels and Revitalizing African Agriculture

›In “A New Hope for Africa,” published in last month’s issue of Nature, authors Lee R. Lynd and Jeremy Woods assert that the international development community should “cut with the beneficial edge of bioenergy’s double-edged sword” to enhance food security in Africa. According to Lynd and Woods, Africa’s severe food insecurity is a “legacy of three decades of neglect for agricultural development.” Left out of the Green Revolution in the 1960s, the region was flooded with cheap food imports from developed nations while local agricultural sectors remained underdeveloped. With thoughtful management, bioenergy production on marginal lands unfit for edible crops may yield several food security benefits, such as increased employment, improved agricultural infrastructure, energy democratization, land regeneration, and reduced conflict, write the authors.

The technological advancements of second-generation biofuels may ease the zero-sum tension between food production and bioenergy in the future, writes Duncan Graham-Rowe in his article “Beyond Food Versus Fuel,” also appearing last month in Nature. Graham-Rowe notes that current first-generation biofuel technologies, such as corn and sugar cane, contribute to rising food prices, require intensive water and nitrogen inputs, and divert land from food production by way of profitability and physical space. There is some division between second-generation biofuel proponents: some advocate utilizing inedible parts of plants already produced, while others consider fast-growing, dedicated energy crops (possibly grown on polluted soil otherwise unfit for human use) a more viable solution – either has the potential to reduce demand for arable land, says Graham-Rowe. “Advanced generations of biofuels are on their way,” he writes, it is just a matter of time before their kinks are worked out “through technology, careful land management, and considered use of resources.” -

Emily Puckart, MHTF Blog

Maternal Health Challenges in Kenya: An Overview of the Meetings

›The original version of this article, by Emily Puckart, appeared on the Maternal Health Task Force blog.

I attended the two day Nairobi meeting on “Maternal Health Challenges in Kenya: What New Research Evidence Shows” organized by the Woodrow Wilson International Center and the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC). [Video Below]

First, here in Nairobi, participants heard three presentations highlighting challenges in maternal health in Kenya. The first presentation by Lawrence Ikamari focused on the unique challenges faced by women in rural Kenya. Presently Kenya is still primarily a rural country where childbearing starts early and women have high fertility rates. A majority of rural births take place outside of health institutions, and overall rural women have less access to skilled birth attendants, medications, and medical facilities that can help save their lives and the lives of their babies in case of emergency.

Catherine Kyobutungi highlighted the challenges of urban Kenyan women, many of whom deliver at home. When APHRC conducted research in this area, nearly 68 percent of surveyed women said it was not necessary to go to health facility. Poor road infrastructure and insecurity often prevented women from delivering in a facility. Women who went into labor at night often felt it is unsafe to leave their homes for a facility and risked their lives giving birth at home away from the support of skilled medical personnel and health facilities. As the urban population increases in the coming years, governments will need to expend more attention on the unique challenges women face in urban settings.

Finally, Margaret Meme explored a human rights based approach to maternal health and called on policymakers, advocates, and donors to respect women’s right to live through pregnancies. Further, she urged increased attention on the role of men in maternal health by increasing the education and awareness of men in the area of sexual and reproductive health as well as maternal health.

After these initial presentations, participants broke out into lively breakout groups to discuss these maternal health challenges in Kenya in detail. They reconvened in the afternoon in Nairobi to conduct a live video conference with a morning Washington, DC audience at the Woodrow Wilson Center. It was exciting to be involved in this format, watching as participants in Washington were able to ask questions live of the men and women involved in maternal health advocacy, research and programming directly on the ground in Kenya. It was clear the excitement existed on both sides of the Atlantic as participants in Nairobi were able to directly project their concerns and hopes for the future of maternal health in Kenya across the ocean through the use of video conferencing technology.

There was a lot of excitement and energy in the room in Nairobi, and I think I sensed the same excitement through the television screen in DC. I hope that this type of simultaneous dialogue, across many time zones, directly linking maternal health advocates around the globe, is an example of what will become commonplace in the future of the maternal health field.

Emily Puckart is a senior program assistant at the Maternal Health Task Force (MHTF).

Photo Credit: MHTF.