-

Will the Global Plastics Treaty Safeguard Health?

August 13, 2025 By Dr. Philip J. Landrigan

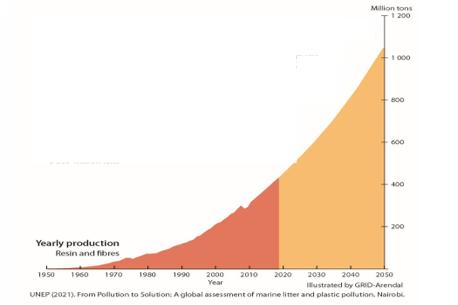

Global plastic production is increasing almost exponentially. Not only has it grown 250-fold since the 1950s, but it is on track to double by 2040, and nearly triple by 2060. The waste associated with its creation has accumulated in parallel. An estimated 8 billion metric tons of discarded plastic now pollute the planet, breaking down into micro-and nanoplastic particles (MNPs) that are ubiquitous in the environment. These microscopic particles and the plastic chemicals they contain enter our bodies via food, water, and air—and can be detected today in virtually every organ of the human body.

Global Plastic Production 1950-2050 To address this crisis, representatives of more than 170 nations are gathered this week in Geneva for the sixth round of negotiations for the Global Plastics Treaty. A key question before the members of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) is whether to design a treaty that will safeguard human health alongside other key elements of the agreement.

The case for including health in the treaty is strong. There is now abundant evidence that plastics are a grave and growing danger to human health. Disease, disability, and premature death occur at every stage of the plastic life cycle: the extraction of gas, oil and coal from which most plastics are made; their actual production and use, and even following their disposal.

The diseases caused by that life cycle are manifold. They include cancers and neurological diseases in plastic production workers, as well as IQ loss, behavioral disruption, and decreased future fertility in children exposed to phthalates from plastic toys. Persons exposed to toxic smoke from the open burning of plastic waste suffer from lung disease. There are also broader increased risks of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke in adults who absorb the widely used plastic chemical, bisphenol A, from food containers and water bottles.

These impacts affect people in all countries. Yet it is essential to note that they fall disproportionately on the poor and the vulnerable. The annual health-related economic losses that attach to plastics are conservatively estimated to exceed $1.5 trillion.

Turning Off the Tap

A plastics treaty that safeguards health must contain two key provisions. One is regulation and a transparent disclosure of information about the thousands of chemicals in plastics, which not only include known carcinogens, neurotoxicants, and endocrine disruptors, but also many more that have never been tested for toxicity. These chemicals are responsible for most of plastics’ known harms to human health.

Yet knowledge and regulation will not be enough. A global cap on plastic production with legally binding targets and timetables also will be essential because continuing, unchecked increases in production are the main driver of plastics’ worsening harms.

The strategy of capping pollution at the source by turning off the tap has proven highly effective in dealing with other threats to health. Known in public health circles as “primary” or “upstream” prevention, it traces its origins to John Snow’s removal of the handle of the Broad Street pump in 19th century London to halt a massive cholera epidemic.

The Broad Street Pump, London Upstream prevention has been shown time and again to be more effective at safeguarding health, more efficient, and more cost-effective than downstream approaches that attempt to clean up pollution after it has been dispersed.

One example is clean air legislation. Air pollution control laws based on upstream prevention have improved air quality in multiple countries. In the US, the Clean Air Act has reduced smoke releases from factories and tailpipe emissions from cars by 75% since its adoption in 1970. The measure also has improved Americans’ health and extended longevity by preventing millions of premature deaths from heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and stroke.

Likewise, the removal of lead from automotive gasoline over the past five decades has resulted in greater than 90% reductions in blood lead levels, improved cognitive function (IQ) in millions of children, and decreased risks of hypertension and heart disease in adults.

Upstream, source-focused interventions also are highly cost-effective. Each dollar invested in air pollution control in the US is estimated to have yielded an economic benefit of $30 through reduced health-care costs and the increased economic productivity of a healthier, longer-lived population.

Raising IQ and extending longevity through the removal of lead from gasoline also has improved the economic productivity of entire nations. In the US, lead removal is estimated to have added $200 billion to the economy across the life span of each annual cohort of children born since 1980—an aggregate benefit over four decades of more than $8 trillion.

Downstream Dallying

The petrostates and the multinational fossil fuel corporations that produce most of the world’s plastic oppose upstream-focused controls. They are increasing their production of plastics year-to-year as global demand for fossil fuels declines. (Plastics have been described as the fossil fuel industry’s “Plan B’”) These entities see pushing the production of disposable, single-use plastics, which now account for 40% of plastic production, as especially promising.

The argument presented by the petrostates and fossil fuel corporations is that plastic pollution can best be controlled by “downstream” approaches. They believe that better collection of plastic waste and enhanced recycling, variously termed “chemical recycling,” “pyrolysis,” and “upcycling,” is the answer.

Recycling would appear to be an attractive strategy for the control of plastic pollution at first blush. Indeed, it works very well for paper, glass, aluminum, and steel. However, three decades of experience make it abundantly clear that recycling does not work for plastic.

Only about 8% of global plastic is recycled and reused. The rest is either burned or dumped into landfills. Plastic recycling fails because most plastics resist recycling. Significant differences between polyvinyl chloride, polyurethane and polyethylene mean that cannot be co-mingled in making recycled products. A further stumbling block? Recycled plastics cannot safely be incorporated into materials such as food packaging, clothing, or children’s toys because of their toxic chemical content. Reuse of plastic waste as motor fuel also is a non-starter, because it contains carcinogens that EPA has estimated will cause cancer in as many as one in four exposed people.

Prospects for Success?

The previous round of negotiations held in Busan, Korea in November 2024 (INC 5.1) ended without a treaty. In that session, the petrostates asserted that health had no place in a plastics treaty, and argued incessantly for downstream approaches to the control of plastic pollution. They successfully used procedural devices to run out the clock, and thus thwart the will of the majority of the world’s nations.

Yet support for the protection of human health as a core objective of the plastics treaty continues to grow. More than 100 UN member states, including the members of the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, are in favor. These nations have been joined by the World Health Organization, as well as by a number of religious leaders, including the Dalai Lama, Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the President of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in the Vatican. All of these voices call now for a treaty that addresses injustice and protects human health against plastic.

The question now is whether INC 5.2 will repeat the sorry history of INC 5.1 and accede to the will of a vocal minority whose only interest is short-term economic gain, or move forward with a treaty that is based on science, informed by compassion, respects the wishes of the majority, and safeguards human health. Within the week, we shall know.

Dr. Philip J. Landrigan is a Professor at Boston College and Director of the Global Observatory on Planetary Health. He received his MD from Harvard Medical School and an MSc in Occupational Medicine from the University of London.

Photo Credits: Licensed by AdobeStock.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.