-

In $800 Billion Economic Stimulus Package, Not a Penny for Family Planning

›February 11, 2009 // By Rachel WeisshaarA House-Senate conference committee, with significant input from the White House, is currently striving to produce a compromise stimulus bill that will satisfy all three players. One item that won’t be in the bill is funding for family planning, which was nixed from the House version late last month. The proposal to include money for contraception—which would have been part of a bundle of funds to help states with Medicaid costs—faced high-profile opposition from conservatives, who argued that it would not stimulate the economy. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, responding to the criticism, countered, “The states are in terrible fiscal budget crises now…one of the initiatives you mentioned, the contraception—will reduce costs to the states and to the federal government.”

It turns out that the debate over whether population growth is a net gain or loss for the economy has been going on for decades. According to Population Matters: Demographic Change, Economic Growth, and Poverty in the Developing World (see ECSP event), edited by Nancy Birdsall, Allen Kelly, and Steven Sinding, in developing countries, rapid population growth slows economic growth, and rapid fertility decline reduces poverty. Furthermore, as described in “Poor Health, Poor Women: How Reproductive Health Affects Poverty,” research by Margaret Greene and Thomas Merrick found that poor reproductive health—which includes unmet need for family planning—negatively impacts certain measures of poverty, including health and educational attainment.

Academics aren’t the only ones exploring these concepts; the popular press has also taken on the question of how population growth affects economic growth. The Christian Science Monitor published “Can Obama’s family-planning policies help the economy?,” which Population Connection’s Marian Starkey criticized for failing to adequately answer the question in its headline. MarketWatch published an op-ed contending that population growth is the world’s biggest economic problem. On the other side of the debate, the Wall Street Journal argued, “A smaller workforce can result in less overall economic output. Without enough younger workers to replace retirees, health and pension costs can become debilitating. And when domestic markets shrink, so does capital investment.”

Population-poverty links are incredibly complex, and it’s worth paying attention to the different dynamics between—and among—developing and developed countries, as well as the distinction between the larger goal of economic growth and the more targeted aim of jumpstarting an economy out of a recession. Nevertheless, policymakers don’t have to be flying blind when it comes to the question of whether access to contraceptives affects economic growth. Demographers and economists have been studying these relationships for a long time, and although they may never have complete answers, they have already come up with some valuable insights. -

Global Public Health: An Agenda for the 111th Congress

›February 11, 2009 // By Gib Clarke This is an exciting time to be working global public health, with more attention and money going to the field in the last decade than perhaps ever before. In the past, the struggle has been to direct more money and attention to these issues, but recent efforts have focused more on maximizing funds’ impact—by strengthening health systems, focusing on prevention, and finishing so-called “unfinished agendas” in maternal health, child mortality, and family planning. In my remarks at a recent panel on foreign policy challenges facing the 111th Congress, I focused on four issues: infectious diseases, neglected health issues, funding, and capacity building.

This is an exciting time to be working global public health, with more attention and money going to the field in the last decade than perhaps ever before. In the past, the struggle has been to direct more money and attention to these issues, but recent efforts have focused more on maximizing funds’ impact—by strengthening health systems, focusing on prevention, and finishing so-called “unfinished agendas” in maternal health, child mortality, and family planning. In my remarks at a recent panel on foreign policy challenges facing the 111th Congress, I focused on four issues: infectious diseases, neglected health issues, funding, and capacity building. -

For Many, Sea-Level Rise Already an Issue

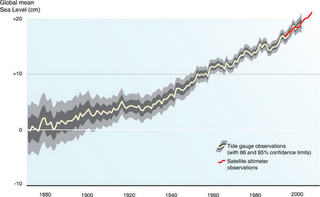

›February 11, 2009 // By Will Rogers Global sea level is projected to rise between 7 and 23 inches by 2100, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Recent melting of the Antarctic ice sheet has prompted geophysicists at the University of Toronto and Oregon State University to warn that global sea level could rise 25 percent beyond the IPCC projections. These catastrophic long-term predictions tend to overshadow the potentially devastating near-term impacts of global sea-level rise that have, in some places, already begun.

Global sea level is projected to rise between 7 and 23 inches by 2100, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Recent melting of the Antarctic ice sheet has prompted geophysicists at the University of Toronto and Oregon State University to warn that global sea level could rise 25 percent beyond the IPCC projections. These catastrophic long-term predictions tend to overshadow the potentially devastating near-term impacts of global sea-level rise that have, in some places, already begun. -

Weekly Reading

›Conflicts among pastoralists over water and land have increased in drought-stricken northeastern Kenya, reports IRIN News.

Country for Sale, a report by Global Witness, alleges that Cambodia’s oil, gas, and mineral industries are highly corrupt.

Foreign Policy features an interview with General William “Kip” Ward, the commander of the new U.S. Africa Command. The New Security Beat covered General Ward’s recent comments on civilian-military cooperation.

Healthy Familes, Healthy Forests: Improving Human Health and Biodiversity Conservation details Conservation International’s integrated population-health-environment projects in Cambodia, Madagascar, and the Philippines.

Double Jeopardy: What the Climate Crisis Means for the Poor, a new report on climate change and poverty alleviation, synthesizes insights from an August 2008 roundtable convened by Richard C. Blum and the Brookings Institution’s Global Economy and Development Program at the Aspen Institute.

“Although the long-term implications of climate change and the retreating ice cap in the Arctic are still unclear, what is very clear is that the High North is going to require even more of the Alliance’s attention in the coming years,” said NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer at a seminar on security prospects in the High North hosted by the Icelandic government in Reykjavik.

“I think we will work our way towards a position that says that having more than two children is irresponsible. It is the ghost at the table. We have all these big issues that everybody is looking at and then you don’t really hear anyone say the “p” word,” says UK Sustainable Development Commission Chair Jonathon Porrit, speaking about population’s impact on the environment. Porrit has drawn criticism for his remarks.

A local priest has warned that a Norwegian company’s proposed nickel mines will threaten food security on the Philippine island of Mindoro. -

This Just In: Panel Ponders Perils to Planetary Reporting

›February 6, 2009 // By Peter Dykstra I’m a little over halfway through my brief stay here at the Wilson Center. This fellowship was made possible by CNN: They laid me off, along with my entire science, tech, and environment news team, in December.

I’m a little over halfway through my brief stay here at the Wilson Center. This fellowship was made possible by CNN: They laid me off, along with my entire science, tech, and environment news team, in December.

We’re not alone: Many reporters and producers like us have found new meaning to the phrase “working journalist.” Non-working journalists now represent a significant piece of the pie.

Rightly or wrongly, many top news executives view beats like science and environment as peripheral to the journalistic mission, or at least to the business plan, of their organizations. Attention to these topics in the general media has a hard time competing with things viewed as more central, whether it’s politics or Paris Hilton.

On Thursday, February 12, in the Wilson Center’s Flom Auditorium, we’ll celebrate Lincoln’s 200th birthday by discussing how to make sure science and environment reporting doesn’t perish from this earth.

Two of the most accomplished science and environment reporters in Washington will join us: Seth Borenstein of the Associated Press and Elizabeth Shogren (not yet confirmed) of NPR. Seth and Elizabeth were among the best chroniclers of the environmental controversies that marked the Bush era, and are closely tracking the promised “change” that may (or may not) be underway in the Obama administration. Both are alumni of news organizations that have recently seen traumatic change: Seth as a correspondent for the Washington Bureau of Knight-Ridder, and Elizabeth for the Los Angeles Times.

Also on the agenda is the future of journalism itself: Newspapers as we now know them may be terminally ill; TV broadcast news as we know it may be five or 10 years behind. Panelist Jan Schaffer, director of J-Lab at American University, will bring her expertise on new- and community-based media. J-Lab is a journalism R&D; center, focusing on providing both guidance and financial support to citizen journalism projects. Jan, a former Philadelphia Inquirer editor and Pulitzer Prize winner, will help us see the way to what journalism will look like 10 and 20 years from now.

Space is limited, so RSVP to the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program soon. If you can’t make it to D.C., you can watch the webcast live.

Photo: Peter Dykstra. Courtesy of Dave Hawxhurst and the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Peter Dykstra is the former executive producer for science, technology, environment, and weather at CNN, and a current public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center. He also writes for www.mnn.com. -

Watch: Peter Gleick on Peak Water

›February 5, 2009 // By Wilson Center Staff“The concept of ‘peak water’ is very analogous to peak oil…we’re using fossil groundwater. That is, we’re pumping groundwater faster than nature naturally recharges it,” says Peter Gleick in this short expert analysis from the Environmental Change and Security Program. Gleick, president and co-founder of the Pacific Institute and author of the newest edition of The World’s Water, explains the new concept of peak water.

-

VIDEO: Kent Butts on Climate Change, Security, and the U.S. Military

›February 5, 2009 // By Wilson Center Staff“Climate change is an important issue that can be addressed by all three elements of the national security equation: defense, diplomacy, and development,” says Kent Butts, in this short expert analysis from the Environmental Change and Security Program. Kent Butts, professor of political-military strategy at the Center for Strategic Leadership, U.S. Army War College, makes the case for considering global climate change a nontraditional threat to security and discusses how the U.S. military is reacting to a changing climate.

-

Developed World’s Dominance Declines with Age, Say Demographers

›February 5, 2009 // By Will Rogers “The whole world is aging, and the developed countries are leading the way,” said Neil Howe of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) at a January 27, 2009, Wilson Center discussion of his latest report, The Graying of the Great Powers: Demography and Geopolitics in the 21st Century. Demography is as close as social science comes to predicting the future, Howe explained, presenting the geopolitical consequences of demographic trends over the next 50 years. Howe and co-author Richard Jackson, also of CSIS, were joined by Jennifer Sciubba of Rhodes College, who urged them and other demographers to explore how population trends interact with additional variables, such as environmental degradation, economic recession, and conflict.

“The whole world is aging, and the developed countries are leading the way,” said Neil Howe of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) at a January 27, 2009, Wilson Center discussion of his latest report, The Graying of the Great Powers: Demography and Geopolitics in the 21st Century. Demography is as close as social science comes to predicting the future, Howe explained, presenting the geopolitical consequences of demographic trends over the next 50 years. Howe and co-author Richard Jackson, also of CSIS, were joined by Jennifer Sciubba of Rhodes College, who urged them and other demographers to explore how population trends interact with additional variables, such as environmental degradation, economic recession, and conflict.

Danger: Demographic Decline Approaching

“Populations in most developed countries will not only age, but stagnate or decline,” due to falling fertility and rising longevity, said Howe. Without “sizable immigration,” he warned, the populations of countries like the United States, France, Great Britain, Canada, Germany, and Japan will decline. As developed countries’ populations shrink, they will lose military might, savings and investment, entrepreneurship, and cultural influence. “Voltaire once said that God is on the side of biggest battalions,” Howe reminded the audience.

Developing Toward Greater Peace Jackson explained that the developing world is in the midst of the “demographic transition”—the drops in mortality and fertility that generally accompany economic and social development. Since 1970, the developing world’s overall fertility rate has declined from 5.1 to 2.9 children per woman, and its overall population growth rate has dropped from 2.2 percent to 1.3 percent per year, according to Jackson. Additionally, the median age has risen from 20 to 26 years old, “a cause for hope and optimism about the future,” Jackson argued, as countries with more balanced population age structures tend to be more democratic, prosperous, and peaceful than countries with extremely young ones.

Jackson explained that the developing world is in the midst of the “demographic transition”—the drops in mortality and fertility that generally accompany economic and social development. Since 1970, the developing world’s overall fertility rate has declined from 5.1 to 2.9 children per woman, and its overall population growth rate has dropped from 2.2 percent to 1.3 percent per year, according to Jackson. Additionally, the median age has risen from 20 to 26 years old, “a cause for hope and optimism about the future,” Jackson argued, as countries with more balanced population age structures tend to be more democratic, prosperous, and peaceful than countries with extremely young ones.

But despite the long-term possibility of a world transitioning toward greater peace and prosperity, the developing world will still experience near-term shocks. The timing and pace of the demographic transition varies widely by country and region, with some countries transitioning too fast or too far, said Jackson. These trends could push developing countries toward social collapse by acting “as a kind of multiplier on all the stresses of development,” explained Jackson—for instance, causing China “to lurch even more toward neo-authoritarianism.”

Crisis of the 2020s

Global demographic trends will converge in the 2020s to make that decade “very challenging,” said Howe. The developed world will undergo hyper-aging, population decline, and flattening GDP growth, along with rising pension and health care costs, Jackson noted. The Muslim world will experience a decade of temporary youth bulges, as the large generation that was born between 1990 and 2000 has children. The populations of Russia and Eastern Europe will implode, and Russia’s geopolitical strength and influence will wane. Meanwhile, China will experience a decade of “premature aging”; due to its one-child policy, it will become “gray” before it achieves the per capita GDP of most aging countries.

Demography and Public Policy Sciubba praised the report’s comprehensive, policy-friendly approach to demography, but urged the authors to remain true to the nuances of their topic, even in their conclusions and recommendations. “Policymakers like to know what we don’t know and what we do know. And with population aging and national security, often there’s a lot more of what we don’t know than what we do know,” she said. “Going into the future, we need more of an emphasis on places where policymakers can make a difference,” said Sciubba. “Opportunities matter just as much as challenges.”

Sciubba praised the report’s comprehensive, policy-friendly approach to demography, but urged the authors to remain true to the nuances of their topic, even in their conclusions and recommendations. “Policymakers like to know what we don’t know and what we do know. And with population aging and national security, often there’s a lot more of what we don’t know than what we do know,” she said. “Going into the future, we need more of an emphasis on places where policymakers can make a difference,” said Sciubba. “Opportunities matter just as much as challenges.”Photos: Neil Howe, Richard Jackson, and Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba. Courtesy of Dave Hawxhurst and the Wilson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

Global sea level is projected to rise between

Global sea level is projected to rise between  I’m a little over halfway through my brief stay here at the Wilson Center. This fellowship was made possible by CNN: They laid me off, along with my entire science, tech, and environment news team, in December.

I’m a little over halfway through my brief stay here at the Wilson Center. This fellowship was made possible by CNN: They laid me off, along with my entire science, tech, and environment news team, in December. “The whole world is aging, and the developed countries are leading the way,” said Neil Howe of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) at a January 27, 2009,

“The whole world is aging, and the developed countries are leading the way,” said Neil Howe of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) at a January 27, 2009,  Jackson explained that the developing world is in the midst of the “demographic transition”—the drops in mortality and fertility that generally accompany economic and social development. Since 1970, the developing world’s overall fertility rate has declined from 5.1 to 2.9 children per woman, and its overall population growth rate has dropped from 2.2 percent to 1.3 percent per year, according to Jackson. Additionally, the median age has risen from 20 to 26 years old, “a cause for hope and optimism about the future,” Jackson argued, as countries with more balanced population age structures tend to be

Jackson explained that the developing world is in the midst of the “demographic transition”—the drops in mortality and fertility that generally accompany economic and social development. Since 1970, the developing world’s overall fertility rate has declined from 5.1 to 2.9 children per woman, and its overall population growth rate has dropped from 2.2 percent to 1.3 percent per year, according to Jackson. Additionally, the median age has risen from 20 to 26 years old, “a cause for hope and optimism about the future,” Jackson argued, as countries with more balanced population age structures tend to be  Sciubba praised the report’s comprehensive, policy-friendly approach to demography, but urged the authors to remain true to the nuances of their topic, even in their conclusions and recommendations. “Policymakers like to know what we don’t know and what we do know. And with population aging and national security, often there’s a lot more of what we don’t know than what we do know,” she said. “Going into the future, we need more of an emphasis on places where policymakers can make a difference,” said Sciubba. “Opportunities matter just as much as challenges.”

Sciubba praised the report’s comprehensive, policy-friendly approach to demography, but urged the authors to remain true to the nuances of their topic, even in their conclusions and recommendations. “Policymakers like to know what we don’t know and what we do know. And with population aging and national security, often there’s a lot more of what we don’t know than what we do know,” she said. “Going into the future, we need more of an emphasis on places where policymakers can make a difference,” said Sciubba. “Opportunities matter just as much as challenges.”