-

Portraits of Women From Afghanistan to the DRC

A Conversation on Art and Social Change

›“At the core of human rights and artistic behavior is respect for human dignity. It is this that unites art and justice,” said Jane M. Saks, executive director of the Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media, speaking at an event cosponsored by the Environmental Change and Security Program and the Africa Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Lynsey Addario, MacArthur-winning photographer and former Institute fellow, joined Saks to share striking photographs highlighting the effects of conflict on women and girls around the world. [Video Below]

The Power of Art

“Art is inherently political because it has the power to really engage in social justice,” Saks said. The Institute that she helped found promotes art that pushes boundaries and creates conversations about peace and war, so as to “add to the accepted canon of understanding of conflict.” As part of this effort, the Institute created the exhibition, “Congo Women: Portraits of War,” composed of photographs by Addario and others about violence against women in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Saks hopes that these “photographs saturated with human dignity” will create awareness and, ultimately, influence policy about the conflict in the DRC. The exhibition has traveled to more than 20 locations since its opening. In May 2009 it was installed at the Senate Rotunda during the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings on violence against women in conflict.

Addario, who said her work is drive by a desire to “give the people a voice,” has spent 15 years traveling deep into conflict zones all over the world, including Iraq, Sudan, and Afghanistan.

Women and Childbirth

Addario’s images reveal the often shocking conditions in which women around the world give birth. In Sierra Leone, she documented 18-year old Mamma Seesay, “one of thousands of women who die in childbirth.” Due to a shortage of doctors, lack of transportation, and high rates of child marriage, one in eight women in Sierra Leone die in childbirth. Afghanistan has the second highest rate of maternal mortality in the world, partly because “an Afghan woman will be pregnant up to 15 times in her life,” she said. “When you watch someone who in most other developed nations would survive without question, it’s just not fair.”

Throughout a decade of covering women in Afghanistan, Addario has sought to provide a “balanced picture” of their lives to American audiences. Her photographs show the milestones women have achieved since the fall of the Taliban: graduating college; driving cars; becoming actors, producers, or police officers; getting married; and giving birth.But her coverage of Afghanistan also contains stories like that of Fariba, an 11-year-old girl who doused herself with petrol and set herself on fire after being abused by her parents. The burn ward at the hospital in Kabul is full of such women who commit self-immolation “to escape their lives,” said Addario. An Afghan woman’s life “is worse than a donkey…there is no release for these women.”

“Give Us Your Guns”

In 2009, she went to the tribal areas of Pakistan to meet the Taliban. “Wrapped up like a cigar,” she posed as the wife of former New York Times correspondent Dexter Filkins and went into a room of 30 Taliban fighters “armed to the teeth.” The two spent the day with the Taliban and “by the end, they loved us,” she said. “The whole time they just laughed at us: ‘You Americans, you give money to the Pakistani government and they give it to us!”

While covering the conflict in Darfur, Addario had to convince UN peacekeepers to drive into a Janjaweed-occupied village so that she could verify how many people had been killed. “Every time we would go towards the village, the Janjaweed would shoot at us and so [the peacekeepers] would turn the cars around and go,” Addario said. To convince the peacekeepers to go in anyway, she said to the commander: “Just give us your guns. We’re gonna go in ourselves if you don’t.” When they finally drove towards the village, “the Janjaweed set it on fire right in front of us, and we just kept driving, and when we got there they had left,” she said.

Addario has spent years as a single woman traveling around the world and throughout conflict zones. “Women in Afghanistan think I’m insane,” she said. “They think I have a lonely, miserable life.” But she believes that as a woman working in conflict zones, she has a unique ability to access places that a man could not and a mission to tell the stories that she hears. “For me it’s about showing the greater American public what’s happening.”

Sources: Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media, National Geographic, The New York Times, Public Radio International, Slate, UNICEF, and the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

Photo Credit: Woman in labor with her mother on the way to the hospital in Afghanistan and a U.S. Marine in Afghanistan, used with permission courtesy of Lynsey Addario and the VII Network. -

Edward Carr, University of South Carolina

Why the Poorest Aren’t Necessarily the Most Vulnerable to Food Price Shocks

›February 8, 2011 // By Wilson Center Staff

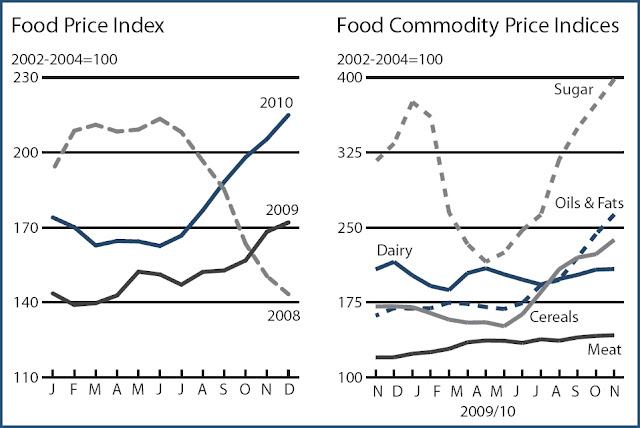

There have been an interesting series of blog posts going around about the issue of price speculation in food markets, and the impact of that speculation on food security and people’s welfare. Going back through some of these exchanges, it seems to me that a number of folks are arguing past one another.

-

Reality Check: Challenges and Innovations in Addressing Postpartum Hemorrhage

›Heavy bleeding after childbirth, also known as postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), is one of the leading causes of maternal deaths worldwide. Globally, approximately 25 percent of all maternal deaths are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, and many mothers bleed to death due to delays in seeking health care services. On January 25th, 100 representatives from the maternal health community – a majority working directly in developing countries – convened for an all-day meeting at the Wilson Center to discuss experiences in the field and perform “reality checks” on the challenges and successes of PPH programs.

-

The International Framework for Climate-Induced Displacement

›In an article sponsored by the East-West Center, author Maxine Burkett discusses the challenges climate-induced migration presents to the people of the Pacific Islands. In the brief, titled “In Search of Refuge: Pacific Islands, Climate-Induced Migration, and the Legal Frontier,” Burkett states that millions of people in the Pacific Islands will be forced to leave their homes because of “increased intensity and frequency of storms and floods, sea-level rise, and desertification.” These low-lying islands could face a loss of agriculture and freshwater resources, or even be wiped out altogether, an outcome for which there is no international legal precedent.

In “Swimming Against the Tide: Why a Climate Displacement Treaty is Not the Answer,” published in the International Journal of Refugee Law, Jane McAdam takes a different position on the plight of so-called “climate refugees.” McAdam argues that focusing on an international treaty for these migrants distracts from efforts to establish responses for adaptation, internal migration, and migration over time. The article, writes the author, “does not deny the real impacts that climate change is already having on communities,” but rather questions the utility and political consequences of “pinning ‘solutions’ to climate change-related displacement on a multilateral instrument.” -

First Steps on Human Security and Emerging Risks

›The 2010 Quadrennial Development and Diplomacy Review (QDDR), the first of its kind, was recently released by the State Department and USAID in an attempt to redefine the scope and mission of U.S. foreign policy in the 21st century. Breaking away from the Cold War structures of hard international security and an exclusive focus on state-level diplomacy, the QDDR recognizes that U.S. interests are best served by a more comprehensive approach to international relations. The men and women who already work with the U.S. government possess valuable expertise that should be leveraged to tackle emerging threats and opportunities.

-

More on Tunisia’s Age Structure, its Measurement, and the Knowledge Derived

›February 4, 2011 // By Richard CincottaThis post is a response to the questions and comments that my fellow demographers Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, Jack Goldstone, and Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba put to my recent assessment of Tunisia’s chances for democracy. I’ve divided my response to address the principal questions. (Note: Throughout, “young adults” refers to 15-24 year olds, and “working age population” refers to those between 15-64 years old.)

1. Tunisia’s age structure is still quite young – aren’t the effects associated with youth bulge still at work?

Tunisia’s age structure (median age, 29 years) is in the early stages of transiting between the instability that typically prevails in countries with youthful age structures (median age <25), and the stability that is typical of mature structures (median age between 35 to 45). I classify Tunisia’s age structure as intermediate (between 25 to 35). The Jasmine Revolution has featured a mix of both types of sociopolitical behavior: some violence and property damage, perpetuated by both the state and demonstrators; evidence of a mature, professionally-led institution (the Tunisian army); and demonstrations that are peaceful and in which women and older people participate.

By any legitimate youth bulge measure, Tunisia’s age-structure is similar to that of South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand’s during the mid-1990s. In 2010, Tunisia’s proportion of young adults in the working age population was almost precisely the same as South Korea’s in 1993. South Korea’s median age in 1993 was 28.5, compared to Tunisia’s 29 today.

Consistent with these numerical similarities, Tunisia’s political behavior is not much different than the sociopolitical events observed in South Korea, Taiwan, or Thailand in the early 1990s when these countries experienced an age structure of similar maturity. As these countries matured, political violence and destructive protests occurred less frequently but dissidence lingered in more peaceful, isolated incidents. For example, South Korea experienced several deadly anti-U.S. demonstrations in 1988-89 and only a few minor incidents in the early 1990s. By 1993, the public was demonstrating against extremism, and public protest had turned peaceful and symbolic.

Even today, public protest in Thailand (median age, 33 years) is commonplace. Thai political rights are constrained, and accordingly the country has been dropped in Freedom House’s annual assessment of political freedoms from “free” to “partly free.” However, unlike the student and worker riots that occurred sporadically throughout the 1970s and 80s, Thai demonstrations are typically non-confrontational political rallies attended by T-shirt-clad grandparents and families who bus into town for the event.

2. Why use the population’s median age rather than the youth bulge measures that political demographers (including me) have previously employed with considerable success?

I’m experimenting, and so far, I’ve found that median age replicates prior published results concerning civil conflict and stable liberal democracy. Median age’s ability to span the entire length of the demographic life-cycle of the state is its primary advantage. Youth bulge indicators do not; neither do indicators focused on working-age adults, nor those measuring seniors. In addition, median age integrates many factors that change in parallel with the age-structural transition, including income, education, women’s participation in society, secularization, and technological progress. Still, median age doesn’t track the youth bulge measures perfectly, so why use it?

Currently, foreign affairs policymakers see few linkages between a country’s (1) risk of civil and political violence; (2) its propensity to accumulate savings and human capital; (3) its chances of attaining stable liberal democracy; (4) the challenges that arise to adequately funding pensions and senior healthcare; and (5) rapid ethnic change in low fertility societies. Political demographers understand that these effects on the state are indeed related and that the rising and ebbing probabilities associated with these effects occur sequentially. Understanding this sequence is key to understanding the world’s international relations future. Median age allows political demographers to view that sequence.

As Jennifer Sciubba points out, the disadvantage of median age is its apparent lack of resonance with theories that have historically informed political demography, including theories of cohort crowding, dependent support, and life-cycle savings. I don’t believe that political and economic demographers should (or will) abandon these indicators, which help them observe the inner workings of age-structural phenomena. Nonetheless, I find it useful to make analysts aware of the advantageous and disadvantageous pressures that age structure exerts across the entire demographic life cycle of the state.

3. Can the deposed regime’s multi-faceted problems be captured by the age-structural transition?

No, age-structure cannot account for leadership – clumsy or deft, corrupt or honest. The method is limited to predictions that draw on sociopolitical behaviors that are associated with age structures, or by knowledge gained from deviations from these predictions. Nonetheless, I question the value of many of the after-the-fact observations of the Ben Ali Regime. Tunisia’s fallen regime was indeed oppressive, corrupt, and nepotistic – but so are most authoritarian regimes in Asia and Africa. Lack of job creation and preferential access to employment are valid grievances across much of the developing world, but the lack of informal sector statistics renders country comparisons difficult.

Some analysts have hypothesized that global warming has been a contributor (also applied to Egypt), others point to economic globalization and pressures on Tunisia’s middle class. Whether these assertions are wrong or right, it is difficult for me to see how such post hoc observations add to analysts’ knowledge of regime change or democratization or help them explain why other countries with similar problems have not undergone similar sociopolitical dynamics. In contrast, hypotheses based on quantitative relationships between age structural indicators and sociopolitical behaviors generate testable and repeatable predictions that can be checked and held accountable after an event.

What I find most surprising about the age-structural approach to predicting liberal democracy is how often states ascend to liberal democracy as they approach, or pass, the 0.50 probability mark. If either “triggers” of regime change or key institutions were very important, this observation would be unlikely.

A Concluding Note on Political Demography

If political demographers are serious about advancing policymakers’ ability to understand the present and future of global politics and security, political demography will have to become a scientific discipline – a field of study in which assertions are consistently tied to data and tested whenever possible. In many cases, though not all, we’re lucky – demographers provide us with timely estimates and projections at the national level. Nonetheless, for our field to succeed, political demographers must take full advantage of these data, encourage sub-national data to be collected and published, and make a clean break from the tradition of conjecture that currently pervades international relations.

Richard Cincotta is a consulting political demographer for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Project and demographer-in-residence at the Stimson Center.

Sources: CIA World Factbook, Freedom House, Jadaliyya.

Image Credit: Adapted from “Viva the Tunisian Revolution,” courtesy of flickr user freestylee (Michael Thompson). -

‘Blood in the Mobile’ Documents the Conflict Minerals of Eastern Congo

›With Blood in the Mobile, Danish director Frank Poulsen dives into the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to document a vicious cycle of conflict that has claimed millions of lives, produced rampant humanitarian abuses, and is driven in part (though not entirely, it should be noted) by the area’s rich mineral resources – all under the noses of the world’s largest peacekeeping operation.

The minerals extracted in the eastern DRC – tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold, mainly from North and South Kivu provinces – are used in cell phones around the world. The trailer shows Poulsen gaining access to an enormous tin mine in the area – the biggest illegal mine in the Congo, he says – capturing powerful footage of the squalid and dangerous conditions that thousands of often-teenage workers labor under for days at a time.

“Four years ago this place was nothing but jungle,” narrates Poulsen. “Today, 15,000-20,000 people are working here [and] different armed groups are fighting to gain control over the mine.”

Though Poulsen is pictured making dramatic phone calls to Nokia (the largest cell phone manufacturer in the world), the issue of conflict minerals from the DRC and places like it is in fact more than just a blip on the radar screens of most leading technology companies. The NGO the Enough Project in particular has been championing the cause and bringing it to tech companies’ doorsteps for quite some time. Their efforts have helped produce an action plan for certifying conflict-free supply chains (complete with company rankings) and also helped lead to passage of the United States’ first law addressing conflict minerals this fall.

However, Poulsen’s message of the developed world taking responsibility for sourcing is commendable. Efforts like this that have led to the adoption of corporate responsibility initiatives like the Cardin-Lugar amendment, a similar measure in the works for the European Union, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and the Kimberley Process for diamonds.

Blood in the Mobile premiered this fall at the International Documentary Film Festival and the producers are “in dialogue with different U.S. distributors,” according to their Facebook page, where those interested are advised to stay tuned.

Sources: BloodintheMobile.org, Enough Project, EurActiv.

Video Credit: Blood in the Mobile Official Trailer. -

Book Preview: ‘The Future Faces of War: Population and National Security’

›February 3, 2011 // By Christina DaggettThe word “population” doesn’t come up too often in national security debates, yet, a shift may be coming, as global population reaches the seven billion mark this year, youth-led unrest rocks the Middle East, and questions of aging enter the lexicon of policymakers from Japan and South Korea to Europe and the United States. What does a population of nine billion (the UN medium-variant projection for 2050) mean for global security? How will shrinking populations in Europe affect Western military alliances and operations? Is demography destiny?

The latter question has plagued demographers, policymakers, and academics for centuries, resulting in heated debate and dire warnings. Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba continues this debate in her new book, The Future Faces of War: Population and National Security, but with a decidedly more measured and optimistic tone (full disclosure: Sciubba was one of my professors). The book is targeted at policymakers but is accessible to anyone with an interest in the field of demography and national security. She will launch her book at an event hosted by the Wilson Center on March 14.

Turning Challenge Into Opportunity

The main themes of The Future Faces of War are challenge and opportunity. Yes, national security will be tested by a series of evolving demographic trends in the decades ahead, but with proper insight and preparation, states can turn these challenges into opportunities for growth and betterment. Sciubba writes, “How a state deals with its demographic situation – or any other situation for that matter – is more important than the trends themselves” (p.125).

Part of turning these population challenges into opportunity is understanding long-term trends – a daunting task given the range and number of trends to consider. Drawing on her own experiences in the defense community, Sciubba writes how policymakers were “receptive” to the idea of population influencing national security, but that the “overwhelming number of ways demography seemed to matter” made them hesitant to act (p.3). With the publication of this book, which clearly and concisely outlines the basics of each population trend with demonstrative examples, hopefully that hesitation will be turned into action.

Youth and Conflict

The first population trend Sciubba highlights is perhaps the one of most immediate concern to national security policymakers given recent world events. In the chapter “Youth and Youthful Age Structures,” Sciubba discusses the security implications of those countries (in particular those in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia) with a majority of their population under the age of 29. She writes, “Most important for national security, countries with youthful age structures are generally the least developed and least democratic in the world, and tend to have the highest risk of civil conflict” (p. 18). In fact, between 1970 and 1999 countries with very young and youthful age structures were two to four times more likely to experience civil conflict than countries with more mature age structures.

The risks of very young and youthful populations are well documented (Sciubba cites the examples of Somali piracy, religious extremism, and child soldiers in Africa), but what has not been as widely discussed are the opportunities. Youthful states have a large pool of potential recruits for their armies, plenty of workers to drive economic development, and even an opportunity to grow democratically through social protest. Sciubba writes, “Youth can also be a force for positive political change as they demand representation and inclusion in the political process… social protest is not always a bad thing, even if it does threaten a country’s stability, because it may lead to more representative governance or other benefits” (p. 23). (For more on youth and the transition to democracy, see “Half a Chance: Youth Bulges and Transition to Democracy,” by Richard Cincotta, and his recent blog post about the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia).

Graying of the Great Powers

At the other end of the demographic transition is population aging. Sciubba points out that the countries with the highest proportions of people aged 60 and older are also “some of the world’s most powerful and economically or politically strategic states” (p. 42). Europe, Japan, and the United States are all getting older (though the United States to a slightly lesser extent), and Sciubba states that the “graying” of these countries has the potential to greatly limit military preparedness, size, and funding. She points out that the number of recruits available will be much smaller and more money will have to be spent on pensions and health care for the growing number of elderly persons.

To counteract these challenges, Sciubba recommends that aging states seek out alliances with each other and countries with younger populations. She writes, “As part of strong alliances, states have strength in numbers, even if they are individually weakened by aging” (p. 47). Another alternative would be to improve military technology and efficiency to compensate for the drop in personnel.

Migration and Security: A “Unique” Relationship

Migration, the third pillar of demographic change after fertility and mortality, has what Sciubba calls a “unique relationship to national security” (p.83). Migration “is the only population driver that can change the composition of a state or a community within months, weeks, or even days” (p. 83). Mass migrations (such as those caused by a natural disaster or violent conflict) are the best examples of this trend. Some of the security challenges Sciubba highlights about migration are refugee militarization, competition for resources, and identity struggles among the native and migrant populations.

However, Sciubba also argues that both migrants and receiving countries can benefit. Origin states release pressure on their crowded labor markets and earn income from remittances, while receiving countries increase their labor market and mitigate population decline (a key component of U.S. growth).

Much of this has been studied before, but two new developments in migration trends that Sciubba calls to our attention are what she calls the “feminization of migration” (the increasing number of women who are likely to move for economic reasons) and migration as a result of climate change. Both are intriguing new areas of inquiry that deserve further study, but only get a passing mention in the book.

Making Her Case

The basic trends outlined above are only a small sampling of the wealth of information to be found in The Future Faces of War. Other noteworthy topics include a discussion on transitional age structures, urbanization, gender imbalances, HIV/AIDS, differential growth among ethnic groups, and many more. The topics are varied and wide-ranging and yet, Sciubba manages to connect them and makes her case convincingly for their inclusion in the broader national security dialogue. Sciubba has briefly written about many of these topics before, but this is the first time she (or anyone else, for that matter) has brought them together in one comprehensive book with such a focus on national security.

Christina Daggett is an intern with ECSP and a former student of Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba’s at Rhodes College.

Sources: Population Action International.

Photo Credits: “Children at IDP Camp Playful During UNAMID Patrol,” courtesy of flickr user United Nations Photo. Book cover image provided by, and used with the permission of, Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba and ABC-CLIO.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.