-

Integrating Development: A Livelihood Approach to Population, Health, and Environment Programs

›

Rural communities in developing countries understand that high population growth rates, poor health, and environmental degradation are connected, said Population Action International’s Roger-Mark De Souza at a recent Wilson Center event. An integrated approach to development – one that combines population, health, and environment (PHE) programs – is a “cost-effective intervention that we can do very easily, that responds to community needs, that will have a huge impact that’s felt within a short period of time,” said De Souza. “This is how we live our lives, this makes sense to us – it’s completely logical,” community participants in PHE projects told him.

-

Carl Haub, Behind the Numbers

UN Releases Early Results of Global Population Projections

›April 18, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Carl Haub, appeared on the Population Reference Bureau’s Behind the Numbers blog.

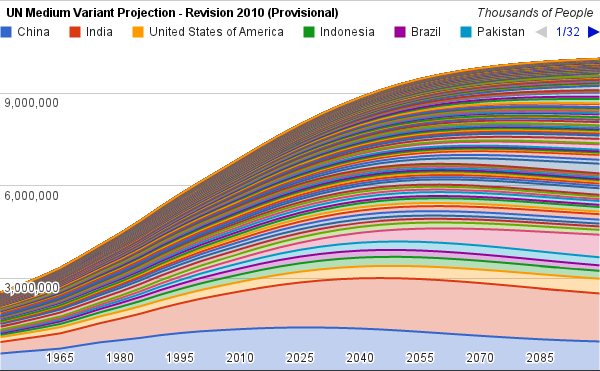

The United Nations Population Division has released preliminary results of its biennial series of population projections for the world’s countries for the 2010 revision. The projections are expected to be finalized later this month.While the global population for 2010 — 6.873 billion — is slightly lower than estimated in the 2008 revision (6.909 billion), the projected population for 2050 is now higher at 9.295 billion compared with the previous 9.150 projected in 2008. That can also be compared to the 2050 population of 9.485 billion on PRB’s 2010 World Population Data Sheet and 9.256 billion in the International Data Base of the U.S. Census Bureau.

The 2010 UN projections differ from the previous series in two significant ways. First, the projection horizon has been extended to 2100, quite far into the future. Second, the UN no longer assumes a uniform “ultimate” level of the total fertility rate (TFR) for all countries, such as the 1.85 level in its medium variant. Instead, multiple possibilities for each country’s TFR are projected with a probabilistic method based on fertility trends for the 1950-2010 period. Then, the median path of those “tracks” serves as the projected TFR for the medium variant series. The high and low variants, however, will be projected as in the past. Those variants have used an “ultimate” TFR of 2.35 and 1.35 for all countries, respectively.

The projected population of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in 2050, the world’s region with by far the largest potential for population growth, is now 1.963 billion, up from 1.753 in the 2008 UN projections. But, since the projections now run to 2100, we can now see beyond mid-century. By 2100, the UN projects that SSA would total an eye-popping 3.4 billion, nearly four times its present size and still be growing by 0.7 percent per year, adding 2 million annually at that time!

Continue reading on Behind the Numbers.

Sources: Population Reference Bureau, UN Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau.

Chart Credit: Data from UN Population Division, created by Schuyler Null. See full chart for interactive version (warning: it’s a lot of data – may slow or crash your browser). -

Climate Adaptation, Development, and Peacebuilding in Fragile States: Finding the Triple-Bottom Line

›“The climate agenda goes well beyond climate,” said Dan Smith, secretary general of International Alert at a recent Wilson Center event. “In the last 60 years, at least 40 percent of all interstate conflicts have had a link to natural resources” and those that do are also twice as likely to relapse in the five years following a peace agreement, said Neil Levine, director of the Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation at USAID. [Video Below]

Development, peace, and climate stability are “the triple-bottom line,” said Smith. “How would you ever think that it would be possible to make progress on one, while ignoring the other two?” Levine and Smith were joined by Alexander Carius, managing director of Adelphi Research, who pointed out that climate change is both a matter of human security and traditional security. For example, as sea-level rise threatens the people of small-island states, “it also affects, in a very traditional sense, the question of security and a state’s sovereignty,” he said.

The Triple-Bottom Line

Conflicts are never attributable to a single cause, but instead are caused by “a whole pile-up, a proliferation, a conglomeration of reasons” that often include poverty, weak governance, traumatic memory of war, and climate change, said Smith. “Climate adds to the strains and the stresses that countries are under,” and works as a “risk-multiplier, or conflict multiplier,” he said.

Focusing development and peace-building efforts on those regions experiencing multiple threats is both a “moral imperative” and a “self-interested imperative,” said Smith. “We benefit from a more prosperous and a more stable world.”

There are currently one and a half billion people in the world living in countries that face these interlinked problems, said Smith, “and interlinked problems, almost by definition, require interlinked solutions.” Responding to the needs of these people requires developing resiliency so that they can respond to the consequences of climate change, which he called “unknown unknowns.”

“What we need are institutions and policies and actions which guard us not only against the threats we can see coming… but against the ones we can’t see coming,” said Smith. The strength and resilience of governments, economies, and communities are key to determining whether climate events become disasters.

Interagency Cooperation

“Part of making the triple-bottom line a real thing is to understand that we will have to be working on our own institutions, even the best and most effective of them, to make sure that they see the interlinkages,” said Smith.

But even though individuals increasingly understand the need to address security, development, and climate change in an integrated fashion, “institutions have only limited capacities for coordination,” said Carius. Institutions are constrained by bureaucratic processes, political mandates, or limited human resources, he said. “Years ago, I always argued for a more integrated policy process; today I would argue for an integrated assessment of the issues, but to…translate it back into sectoral approaches.”

Levine expressed optimism that with “a whole new avalanche of interagency connections” being established in the last few years, U.S. interagency cooperation has become “the culture.” However, if coordination efforts are not carefully aligned to advance concrete programs and policies, they run the risk of “getting bogged down in massive bureaucratic exercises,” he said. “‘Whole of government’ needn’t be ‘all of government,’ and it needn’t be whole of government, all of government, all the time.”

Building Political Will

Europe has a “conducive political environment to making [climate and security] arguments,” said Smith, but the dialogue has yet to translate into action. In 2007, the debate on climate and security was first brought to the UN and EU with a series of reports by government agencies and the first-ever debate on the impacts of climate change on security at the UN Security Council, said Carius. However, none of the recommendations from the reports were followed and “much of the political momentum that existed…ended up in a very technical, low-level dialogue,” he said.

More recently, the United Kingdom included energy, resources, and climate change as a priority security risk in their National Security Strategy. And Germany, which joined the UN Security Council as a rotating member this year, is expected to reintroduce the topic of climate and security when they assume the Security Council Presidency in July. These steps may help to regain some of the political momentum and “create legitimacy for at least making the argument – the very strong argument – that climate change has an impact on security,” said Carius.

Sources: AFP, UK Cabinet Office, Telegraph, United Nations

Image Credit: “Trees cocooned in spiders webs after flooding in Sindh, Pakistan” courtesy of flickr user DFID -

Youth Bulge, Demography-Security Dialogue, and NATO

PRB Discussion on Population and National Security

›April 14, 2011 // By Schuyler NullThe Population Reference Bureau (PRB) held an online discussion this week with demographer Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba of Rhodes College on the topic of “Population and National Security.” On tap were questions on sex ratios, youth bulge, the definition of “national security,” whether the United States should be giving population and health-related advice, and other demographic security topics. Click through to PRB for the full transcript, or check out some select questions from ECSPers Richard Cincotta, Geoff Dabelko, and Schuyler Null below:

Richard Cincotta: Jennifer, my concern is with the lack of specificity that seems inherent in the youth bulge model in terms of civil and ethnic conflict. In other words, the highest probability of civil conflict (often protracted) is associated with very young populations – the Afghanistan, Iraq, sub-Saharan African situations. But, there is also a situation that arises among populations that are demographically somewhat older that is associated with democratization (i.e., the North African situation). These seem to have been conflated by the press and political scientists, yet they are demographically and politically very different cases. Any thoughts on how to recognize these and separate them?Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba: Rich, I think that until we have a stronger theoretical foundation for understanding the conditions under which a “youthful” population leads to civil conflict (very young pop) or democracy (slightly older pop) it will be hard to relay the difference in these two structures to non-experts. The democratization connection, in particular, needs to be refined to move firmly away from correlation and into causation. Right now, it seems to me that we give the same theoretical reasoning to both conflict and democratization (motive, cohort crowding). Do you agree?

Geoff Dabelko: Is the security community, so accustomed to framing issues as threats, internalize your messages about opportunity? Is there a recognition that low cost interventions such as provision of voluntary family planning services could be part of a holistic sustainable security approach? What are the steps that would need to happen to gain more adherents to this perspective?

(Editor: Read more discussion between Cincotta and Sciubba here and here)Sciubba: I’m sorry to say, but no, not really. The positive perspective does not resonate much because most in defense and intelligence are tasked with imagining the worst-case scenario. Opportunities and happy stories just do not fit in this paradigm (or even most of their job descriptions). I’ve tried to figure out what needs to happen to get them to pay attention to prevention, and the only place I see some chance of breaking through is in discussing Afghanistan. Many realize the challenges posed by Afghanistan’s young and growing population and there is some recognition that family planning may be relevant there. I think that for a paradigmatic shift to occur, it would have to be top-down – the vision of the President, Secretary of Defense, etc.

Dabelko: What would be the benefits of demographers and population experts taking more seriously a dialogue with the security community? Your book shows why security sector actors should pay attention to demography. Why should demographers pay attention to security?Sciubba: Some in the security community don’t necessarily understand the assumptions behind demographic projections or other aspects of the data, which means they sometimes misuse the info or distrust it and discard it all together. I also think that scholars of any discipline have a responsibility to understand how their work is being used.

Dabelko: What will be the subject of your next book?Sciubba: I’ll be returning to the politics of population aging. I’m particularly interested in comparing how different regime types have dealt with these issues, including not just Western European states, but also states like Singapore and Russia.

Schuyler Null: There’s been a lot of talk about how aging populations in Europe will affect defense sectors there, in terms of shifting budget priorities. But there’s also the aspect of how aging might affect European decision-making processes when it comes to foreign intervention (perhaps less willing put boots on the ground, stay for long, etc.).

Can you speak to how aging might affect the decision-making process and behavior of European countries when it comes to conflict in the future? How might aging affect the operation of NATO or the UN?Sciubba: Isn’t France a puzzle right now given your question? France, a low fertility country with an aging population and HUGE challenges ahead in terms of paying for entitlements to seniors, has recently shown a greater willingness to contribute to military missions. There is no doubt that aging states in Europe will be under strain trying to meet their promises to seniors and also maintain defense. But, European states still feel that there are sufficient threats in the world to warrant maintaining a military. They are trying to reduce redundancies among themselves and increase their efficiency – great cost-saving measures. Technology can compensate a bit as well. I think European states are willing to use their militaries when the threat is sufficient. Aging, however, may raise the threshold for what qualifies as “sufficient” and US-European opinions on what qualifies may increasingly diverge.

See the full transcript of questions and Sciubba’s responses at the Population Reference Bureau. -

Madagascar, Past and Future: Lessons From Population, Health, and Environment Programs

›In Madagascar, “today’s challenges are even greater than those faced 25 years ago,” said Lisa Gaylord, director of program development at the Wildlife Conservation Society. At an event at the Woodrow Wilson Center on March 28, Gaylord and her co-panelists, Matthew Erdman, the program coordinator for the Population-Health-Environment Program at Blue Ventures Conservation, and Kristen Patterson, a senior program officer at The Nature Conservancy, discussed the challenges and outcomes of past and future integrated population, health, and environment (PHE) programs in Madagascar. [Video Below]

Nature, Health, Wealth, and Power

Gaylord, who has worked in Madagascar for nearly 30 years, gave a brief history of USAID’s activities on the unique island, which she called a “mini-continent.” She used the “nature, health, wealth, and power” framework to review the organization’s environment, health, and livelihoods programs in Madagascar and their results. Governance, she said, is the centerpiece of this framework, but this piece “maybe didn’t have an adequate foundation” in Madagascar to see the programs through the political crisis.

Though its programs started at the community level, Gaylord said USAID’s objective was to scale up to larger levels. “You can’t always work on that level and have an impact,” she said, and there was “tremendous hope” in 2002 for such scaling up when Madagascar elected a new president, Marc Ravalomanana.

Unfortunately, changes in funding, a lack of economic infrastructure, and poor governance forced development programs to scale down. After President Ravalomanana was overthrown in a military coup in 2009, the situation got worse – the United States and other donors pulled most funding, and only humanitarian programs were allowed to continue.

“What worries me is that I think we have gone back” to working on a village level, Gaylord said. “We want to go up in scale, and I think that we felt that we could in Madagascar, but that’s where you have the political complexities that didn’t allow us to continue in that direction.”

Going forward, Gaylord said that it is important to maintain a field-level foundation, take the time to build good governance, and maintain a balance in the funding levels so that no one area, such as health, dominates development activities.

Living With the Sea

Based in southwestern Madagascar, the Blue Ventures program began as an ecotourism outfit, said Erdman, but has since grown to incorporate marine conservation, family planning, and alternative livelihoods. One of its major accomplishments was the establishment of the largest locally managed marine protection area in the Indian Ocean, called Velondriake, which in Malagasy means “to live with the sea.” This marine area covers 80 kilometers of coastline, incorporates 25 villages, and includes more than 10,000 people. The marine reserves for fish, turtles, and octopus, as well as a permanent mangrove reserve, protect stocks from overfishing.

One of the biggest challenges facing the region is its rapidly growing population, which threatens the residents’ health and their food security, as well as the natural resources on which they depend. More than half the population is under the age of 15 and the infant and maternal mortality rates are very high, Erdman explained. Blue Ventures, therefore, set up a family planning program called Safidy, which means “choice” in Malagasy.

“If you have good health, and family size is based on quality, families can be smaller and [there will be] less demand for natural resources, leading to a healthier environment,” said Erdman.

The region’s isolation and lack of education and health services are a challenge, said Erdman, but over the past three years, the contraceptive prevalence rate has increased dramatically, as has the number of clinic visits. The program uses a combination of clinics, peer educators, theater presentations, and sporting events, such as soccer tournaments, to spread information about health and family planning.

A Champion Community

“There is a long history of collaborative work in Madagascar,” Patterson said. Focusing on the commune (county) level, she worked in conjunction with USAID, Malagasy NGOs, and government ministries to try to scale up PHE programs in Madagascar’s Fianarantsoa province, which has a target population of 250,000 people.

“We essentially worked at two different levels,” said Patterson. At the regional level, a coordinating body for USAID and local partners called the “Eco-Regional Alliance” met monthly. The “Champion Commune” initiative, which worked at local levels, had three main goals, she explained:

Though working in such remote areas is expensive, and all non-humanitarian U.S. foreign aid has been suspended since the coup, Patterson hopes that development programs will return to Madagascar. Pointing to its vast rural areas, she stressed the importance of integrated efforts: “The very nature of multi-sectoral programs is that they have the highest benefit in the areas that are most remote. These are the areas where people are literally left out in the cold.”- Create a strong overlap with neighboring communes;

- Promote activities that benefited more than one sector (such as reforesting with vitamin-rich papaya trees); and

- Capitalize on the prior experiences of Malagasy NGOs in implementing integrated projects to help build up civil society.

Image credit: “Untitled,” courtesy of flickr user Alex Cameron.

Sources: The New York Times, Velondriake. -

In Search of a New Security Narrative: National Conversation Series Launches at the Wilson Center

›The United States needs a new national security narrative, agreed a diverse panel of high-level discussants last week during a new Wilson Center initiative, “The National Conversation at the Woodrow Wilson Center.”

Hosted by new Wilson Center President and CEO Jane Harman and moderated by The New York Times’ Thomas Friedman, the inaugural event was based on a white paper by two active military officers writing under the pseudonym “Mr. Y” (echoing George Kennan’s “X” article). In A National Strategic Narrative, Captain Wayne Porter (USN) and Colonel Mark Mykleby (USMC) argue that the United States needs to move away from an outmoded 20th century model of containment, deterrence, and control towards a “strategy of sustainability.” [Video Below]

Anne-Marie Slaughter of Princeton University, who wrote the white paper’s preface, summarized it for the panel, which included Brent Scowcroft, national security adviser to President Ford and President H.W. Bush; Representative Keith Ellison (D-Minn.); Steve Clemons, founder of the American Strategy Program at the New America Foundation; and Robert Kagan, senior fellow for foreign policy at the Brookings Institution.Framing a 21st Century Vision

We can no longer expect to control events, but we can influence them, Slaughter said. “In an interconnected world, the United States should be the strongest competitor and the greatest source of credible influence – the nation that is most able to influence what happens in the international sphere – while standing for security, prosperity, and justice at home and abroad.”

“My generation has had our whole foreign policy world defined as national security,” said Slaughter, “but ‘national security’ only entered the national lexicon in the late 1940s; it was a way of combining defense and foreign affairs, in the context of a post-World War II rising Soviet Union.”

As opposed to a strategy document, their intention, write Porter and Mykleby, was to create a narrative through which to frame U.S. national policy decisions and discussions well into this century.

“America emerged from the Twentieth Century as the most powerful nation on earth,” the “Mr. Y” authors write. “But we failed to recognize that dominance, like fossil fuel, is not a sustainable source of energy.”It is time for America to re-focus our national interests and principles through a long lens on the global environment of tomorrow. It is time to move beyond a strategy of containment to a strategy of sustainment (sustainability); from an emphasis on power and control to an emphasis on strength and influence; from a defensive posture of exclusion, to a proactive posture of engagement. We must recognize that security means more than defense, and sustaining security requires adaptation and evolution, the leverage of converging interests and interdependencies. [italics original]

Prosperity and Security a Matter of Sustainability

The “Mr. Y” paper is similar in some respects to other strategic documents that have promoted a more holistic understanding of security, such as the State Department’s Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, which was partially authored by Slaughter during her time in State’s Policy Planning Office. But there’s a markedly heavy focus on economics and moving beyond the “national security” framework in Porter and Mykleby’s white paper. They outline three “sustainable” investment priorities:

“These issues have come in and out of the security debates since the end of the Cold War, but they have not been incorporated well into a single national security narrative,” Geoff Dabelko, director of the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program, told The New Security Beat. “This piece is a positive step toward achieving a coherent and inclusive national security narrative for the United States.”- Human capital: refocus on education, health, and social infrastructure;

- Sustainable security: use a more holistic, whole-of-government approach to security; essentially, expand the roles of civilian agencies and promote stability as much as ensuring defense; and,

- Natural resources: invest in long-range, sustainable management of natural resources, in the context of expanding global demand (via population growth and consumption).

To provide a “blueprint” for this transition, Porter and Mykleby call for the drafting of a “National Prosperity and Security Act” to replace the national security framework laid by the National Security Act of 1947 (NSA 47) and followed by subsequent NSAs.A New Geostrategic Model?

The panel unanimously praised the white paper’s intentions, if not its exact method of analysis and proposed solutions. All agreed that globalization and technology have helped create a more interconnected and complex world than current foreign policy and national security institutions are designed to deal with. Scowcroft called the 20th century “the epitome of the nation-state system” and said he expects an erosion of nation-state power, especially in light of integrated challenges like climate change and global health.

Kagan disagreed, saying he’s less convinced that the nation-state is fading away. “If anything, I would say since the 1990s, the nation-state has made a kind of comeback,” he said, adding that the paper lacks “a description of how the world works, in the sense of ‘do we still believe in a core realist point that power interaction among nation states is still important?’” In that sense, he said, “I’m not at all convinced we’ve left either the 20th century or the 19th century, in terms of some fundamental issues having to do with power.”

“I think there are three things that really are new,” said Slaughter. “The first [is the] super-empowered individual…the ability of individuals to do things that only states could.” We saw that with 9/11, with individuals attacking a nation, and we’re seeing that with communications as well, she said. “I can tell you, Twitter and the State Department’s reporting system, they’re pretty comparable and Twitter’s probably ahead, in terms of how much information you can get.”

Second, there is a “whole other dimension of power that simply did not exist before and that is how connected you are,” Slaughter said. “The person who is the most connected has the most power, because they’re the person who can mobilize, like Wael Ghonim in Egypt.”

Third, there are a greater number of responsible stakeholders. “What President Obama keeps telling other nations is ‘you want to be a great power? It’s not enough to have a big economy and a big army and a big territory, you have to take responsibility for enforcing the norms of a global order,’” Slaughter said. Qatar’s willingness to participate in the international community’s intervention in Libya, she said, was in part an example of a country responding to that challenge and stepping up into a role it had not previously played.

These new dimensions to power and security don’t entirely replace the old model but do make it more complex. “It’s on top of what was,” Slaughter said, and “we have to adapt to it.”

Photo Credit: Colonel Mark Mykleby (USMC), Captain Wayne Porter (USN), and Wilson Center President and CEO Jane Harman, courtesy of David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

Watch: Elizabeth Leahy Madsen Explains the Demography-Civil Conflict Interface in Less Than Two Minutes

›April 12, 2011 // By Schuyler Null“We know that historically, as well as in the present, countries that have very young age structures – those that have youthful and rapidly growing populations – have been the most vulnerable to outbreaks in civil conflict,” said Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, senior research associate at Population Action International, in an interview with ECSP. “It’s not a simple cause and effect relationship, but we think that demographic trends and pressures can exacerbate underlying conditions.”

-

John Warburton, China Environment Series

UK Helping to Relieve Climate-Related Stress on China’s Agriculture

›The UK and China have been working together since 2001 to better understand how China is going to be impacted by climate change, particularly in the agriculture sector. But understanding must also lead to action, with adaptation needing to be integrated into the development process at both national and local levels. This work, which is ongoing, will increasingly provide a model for how to approach adaptation in other countries.

In my opinion, this work has also contributed to the realization among top-level Chinese officials that it is important to take global action on climate change as part of the international negotiation process; until very recently, most of the international engagement with China has focused on mitigation, with the result that the very real and urgent challenges that China faces in regards to its own adaptation needs have been sidelined.

Another Stressor for Chinese Agriculture

China’s Polices and Actions for Addressing Climate Change, issued in October 2008, state:The impacts of future climate change on agriculture and livestock industry will be mainly adverse. It is likely there will be a drop in the yield of three major crops — wheat, rice and corn; …enlarged scope of crop diseases and insect outbreaks; [and] increased desertification.

Even though assessing the likely impacts of climate change on crop yields is a complicated process, with some evidence showing that in some areas crops may benefit if agricultural technology can keep pace, the overall picture is grim for China.

Potential climate impacts are very worrying for a country which already faces so many other challenges within the agricultural sector, among them the facts that it has to feed nearly one quarter of the world’s population (1.3 billion people) with only seven percent of the world’s arable land; that it has only one-quarter of the world’s average per capita water distribution (one-tenth in large parts of northern China, which are heavily dependent upon agriculture); and that the agricultural land base is fast diminishing due to urbanization, industrialization, and the conversion of arable land to grasslands and forest.

Collaboration on Adaptation

Much of the evidence that supports the understanding of the likely adverse impacts on Chinese agriculture from climate change stems from collaborative work between the UK and China which started in 2001. A joint project, Impacts of Climate Change on Chinese Agriculture (ICCCA), has combined cutting-edge scientific research with practical development policy advice. Although national in scope, the project included pilot work to develop a stakeholder based approach to adaptation in the Ningxia region of northcentral China. ICCCA was successfully completed in December 2008. The UK-China collaboration is now continuing with a major new project which is going beyond agriculture and looking at additional socioeconomic sectors and geographic areas.

Continue reading in the China Environment Forum’s China Environment Series 11, from the Wilson Center. Other articles in the series can be found on CEF’s website.

John Warburton is a DFID senior environment adviser and is currently based in Beijing.

Photo Credit: “Field,” courtesy of flickr user totomaru.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.