-

Watch: Ann Blanc on Finding Unique Partnerships to Address Maternal Health Needs

› In the last five years, maternal health has begun to take a front seat within the larger global health agenda, but when it comes to a neutral space for broader focusing and prioritizing efforts there is still a void. In 2008 the Gates Foundation created the Maternal Health Task Force (MHTF) in an effort to fill that void. In this interview with ECSP, former MHTF Director Ann Blanc discusses how collaboration with the Wilson Center and the United Nations Population Fund has created an ideal space for addressing the technical, programmatic, and policy sides of neglected maternal health issues.

In the last five years, maternal health has begun to take a front seat within the larger global health agenda, but when it comes to a neutral space for broader focusing and prioritizing efforts there is still a void. In 2008 the Gates Foundation created the Maternal Health Task Force (MHTF) in an effort to fill that void. In this interview with ECSP, former MHTF Director Ann Blanc discusses how collaboration with the Wilson Center and the United Nations Population Fund has created an ideal space for addressing the technical, programmatic, and policy sides of neglected maternal health issues.

“Part of our mandate,” Blanc noted, “is to bring in the perspective of what we call ‘allied fields.’” The Wilson Center’s Advancing Policy Dialogue to Improve Maternal Health series focuses on engaging with neglected and emerging topics and experts, finding connections and encouraging partnerships with other fields, such as those working in water, sanitation, or HIV/AIDS services.

For instance, a two-day conference last year with private meetings and public dialogues focused on the neglected issue of transportation for women seeking maternal health services. The conference brought together non-traditional actors, including transportation engineers and mobile technology experts, to identify common barriers mothers commonly face like lack of infrastructure, poor security, or limited access to emergency communications.

“We’re constantly trying to push those barriers and look for interconnections between different development sectors and maternal health,” Blanc concluded. -

Improving Maternal Health: A Conversation With Kenyan Field Workers and Policymakers

›“The traditional strategies for improving the health system include the horizontal approach, which prioritizes non-communicable diseases, and the vertical approach which prioritizes communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS,” said John Townsend, vice president of reproductive health programs at Population Council, during a webcast discussion – the second in a series – between the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, DC, and maternal health experts in Nairobi, Kenya. [Video Below]

Recently, a third strategy, called the “diagonal approach,” was developed to more clearly define health system priorities and guide general system-wide improvements. Participants in both locations discussed this new approach and other structural improvements that can be made to better integrate maternal health indicators into developing country health systems on October 17.

The meeting was part of the 2011 Advancing Dialogue on Maternal Health series, with the Wilson Center’s Global Health Initiative and the African Population and Health Research Center. Participants in Nairobi were assigned to three topical groups and asked to identify challenges and opportunities related to their themes.

The Role of Policymakers and Funders

“We must engage [policymakers and donors] in forums like this one to share findings and share lessons learned,” said participant Sylvia Bushuru of Kenya as she reported back from the policymakers and funders working group. The group focused on steps required to hold politicians accountable to commitments made to maternal health, such as the Abuja Declaration, which requires the Ministry of Finance to dedicate 15 percent of the budget to health. Currently, only 5.5 percent of the Kenya budget is dedicated to the health sector.

Identifying strategic partners will help in reaching ambitious goals, the group agreed; however, they noted that it’s important to ensure that these partnerships and policies extend to an operational level. Besides the overall budget pledge, important steps like ensuring 24-hour emergency health facilities in rural areas and implementing a results-based financing plan based on maternal health indicators have yet to be completed.

A Definition of Priorities through a Diagonal Approach

James Wariero, a regional health advisor with the MDG Centre for East and South Africa, served as the representative for the group discussing the “diagonal approach,” which focused on how maternal health indicators can best set priorities to improve the overall health system. They identified antenatal care visits as a priority because they also serve as an entry point to other health services, including HIV/AIDS treatment.

Discussing gender, he said that “male involvement in maternal health will have benefits for child health and other issues…it is an area with little headway here in Kenya and other similar countries in Africa.” Additionally, Wariero discussed how the diagonal approach could be used to link maternal health indicators with other sectors such as technology and information systems.

The group said that improving the health system should start at the district level to ensure the most vulnerable populations at the community level have proper access. However, they said that ideally district-level programming should be evaluated and funded through results-based financing and structured on clear maternal health indicators.

Knowledge Gaps and Research Needed

“We initially began our discussion surrounding the [World Health Organization’s] six health system blocks,” reported Dr. Kristine Kisaka, a program officer with Deutsche Stiftung Weltbevoelkerung and representative from the “knowledge gaps and research needed” group. This group identified access to mobile phones for maternal health data collection as a major resource gap. Instead of calling for additional research they said they would prefer better implementation of existing, evidence-based programming.

Utilizing the World Health Organization’s health system framework, the group identified existing knowledge gaps to improve maternal health in Kenya and six recommendations:- Strengthen community strategies through a national synchronization of information

- Harmonize planning and implementation of the provisioning of supplies and commodities at the community level

- Address inequalities in the distribution and delivery of health services, ensuring distribution to urban and rural centers, including slums

- Centralize health financing in order to reach both national and community levels

- Empower households in financing, including both women and men, so they plan and save for maternal health

- Address the imbalance in supply and demand of healthcare workers

Linkages: Key To Improving Maternal Health Systems

“It’s really about linkages,” said John Townsend, giving closing remarks after the presentations from Nairobi. Maternal health indicators can be a catalyst for change, due to their strong cross-cutting links to other development systems, such as transportation, the economy, and education. “I think the call to action that the Kenyan working groups made is quite valuable,” he said, but the question is, “How do we get intelligent decision alternatives in front of our leaders to figure out what are the best investments given the critical resources?”

“The private sector [presents] an opportunity,” said Townsend. “I think we need to be more explicit about how we want to engage with them and what we would like to see from them.” He pointed out that the national maternal health strategy in Kenya is explicit and promising, but there needs to be stronger links between the national strategy and the operational aspects of actually implementing it.

Event Resources:- Photo gallery

- Presentation: “Improving Health Systems Through a Maternal Health Framework,” African Population and Health Research Center

- Video

Photo Credit: #1 and #3, courtesy of Jonathan Odhong, African Population and Health Research Center; #2 courtesy of David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

Good Company: ‘New Security Beat’ Honored for Best Population Commentary

›The Population Institute’s 2011 Global Media Awards go to a Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist, the head of the UN Population Fund, PBS NewsHour – and us! We’re thrilled to announce that the New Security Beat has won its third Global Media Award for Best Online Commentary or Blog.

Our company in this year’s line-up is impressive:- PBS NewsHour, for several segments related to population issues, including one on an Indonesian plant showing promise for male birth control and another on how religion and tradition are clashing with family planning efforts in Guatemala;

- Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, Executive Director of UNFPA, for his editorial in Science, “Population and Development;”

- EarthSky: A Clear Voice for Science, for their series of weekly interviews with scientists around the world, including a series with population experts.

- Population Action International (PAI), for their short film Weathering Change, which tells stories about the impact of climate change on women from Ethiopia, Nepal, and Peru (and which was launched at the Wilson Center).

New Security Beat also got a nice shout-out from Andy Revkin on Dot Earth this week for our “seven billion” stories and coverage from South by Southwest Eco. For more on “seven billion” be sure to read Elizabeth Leahy Madsen’s breakdown of how we got to this milestone, Geoff Dabelko’s take on seven ways seven billion will affect the planet, the webcast of our recent reporting on population and environment event, and our latest YouTube videos, including PAI’s Roger-Mark De Souza presenting at South by Southwest Eco. -

Michael Kugelman for Seminar

Safeguarding South Asia’s Water Security

›November 4, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Michael Kugelman, appeared in the public policy journal Seminar.

In today’s era of globalization, the line between critic and hypocrite is increasingly becoming blurred. Single out a problem in a region or country other than one’s own, and risk triggering an immediate, yet understandable, response: Why criticize the problem here, when you face the same one back home?

Such a response is particularly justified in the context of water insecurity, a dilemma that afflicts scores of countries, including the author’s United States. In the parched American West, New Mexico has only 10 years-worth of drinking water remaining, while Arizona already imports every drop. Less arid areas of the country are increasingly water-stressed as well. Rivers in South Carolina and Massachusetts, lakes in Florida and Georgia, and even the mighty Lake Superior (the world’s largest fresh-water lake) are all running dry. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, if American water consumption habits continue unchecked, as many as 36 states will face water shortages within the next few years. Also notable is the fact that America’s waterways are choked with pollution, and that nearly twenty million Americans may fall ill each year from contaminated water. Not to mention that more than thirty U.S. states are fighting with their neighbors over water.

Such a narrative is a familiar one, because it also applies to South Asia. However, in South Asia, the narrative is considerably more urgent. The region houses a quarter of the world’s population, yet contains less than five percent of its annual renewable water resources. With the exception of Bhutan and Nepal, South Asia’s per capita water availability falls below the world average. Annual water availability has plummeted by nearly 70 percent since 1950, and from around 21,000 cubic meters in the 1960s to approximately 8,000 in 2005. If such patterns continue, the region could face “widespread water scarcity” (that is, per capita water availability under 1,000 cubic meters) by 2025. Furthermore, the United Nations, based on a variety of measures – including ecological insecurity, water management problems and resource stress – characterizes two key water basins of South Asia (the Helmand and Indus) as “highly vulnerable.”

These findings are not surprising, given that the region suffers from many drivers of water insecurity: high population growth, vulnerability to climate change, arid weather, agriculture dependent economies, and political tensions. This is not to say that South Asia is devoid of water security stabilizers; indeed, its various trans-national arrangements, to differing degrees, help the region manage its water constraints and tensions. This paper argues that such arrangements are vital, yet also incapable of safeguarding regional water security on their own. It asserts that more attention to demand-side water management within individual countries is as crucial for South Asian water security as are trans-national water mechanisms.

Continue reading on Seminar.

Michael Kugelman is a program associate for the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Sources: The American Prospect, Jaitly (2009), The New York Times, UNEP, UN Population Division, Washington Post.

Video Credit: “Groundwater depletion in India revealed by GRACE,” courtesy of flickr user NASA Goddard Photo and Video. For more on the visualization, see the story on NASA’s Looking at Earth. -

Pascal Gakwaya Kalisa, PHE Champion

Coffee Farmer and Extension Manager Promotes Improved Health and Livelihoods in Rwandan Coffee Communities

›

This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project.

Mr. Pascal Gakwaya Kalisa has produced coffee in the densely populated country of Rwanda for the past nine years. A proud member of the 1,200 member Maraba Coffee Cooperative in Huye District in the Southern Province of Rwanda, Kalisa knows that a larger income alone does not ensure a better quality of life for his fellow coffee farmers and their families. He also knows that a successful coffee growing/exporting enterprise depends on preserving the fragile Rwandan soils, as well as on the health and well-being of farming families and communities. Therefore, Kalisa and other cooperative members treat the land and trees with a level of personal care that is necessary for optimum organic production and soil preservation.

Kalisa and the community have set up small, garden-sized coffee farms that are more productive than usual. Cooperative washing stations have enabled the small-scale farmers to improve product quality, and the cooperatives themselves are learning to negotiate better coffee prices with international buyers. Through such efforts and the support of many international donors and industry partners, Rwanda has become a producer of high quality specialty coffee since 2005, and its coffees are being marketed through renowned coffee roasters and importers in the United States, Europe, and Japan. In just six short years, Rwandan farmers have doubled their incomes and created 2,000 jobs, and the first renowned specialty coffee competition Cup of Excellence in Africa was held in Rwanda in 2008.

SPREAD: A Community Partnership

Recognizing the broad-based health, social, and economic needs of coffee farmers and their families in this part of East Africa, the U.S Agency for International Development initiated the Sustaining Partnerships to Enhance Rural Enterprise and Agribusiness Development project (SPREAD) to provide rural cooperatives and enterprises involved in high-value commodity chains with both appropriate technical assistance and access to health-related services and information. It is this combination of technical assistance and health-related outreach and services that has resulted in increased and sustained incomes and improved livelihoods.

Kalisa and other members of various cooperatives that SPREAD supports recognize that not only should farmers and their families preserve the land, but they must also preserve their own health in order to perform the labor needed to farm the crop that will produce the steady stream of high quality coffee upon which their livelihoods depend. Initiating community dialogues around issues such as protected sex, gender roles, and how coffee revenue is spent within households has also been crucial to project success among both youth and adults.

In his role as coffee zone coordinator for the SPREAD project, Kalisa works with coffee cooperatives to implement improved agricultural practices that improve the quality of their crop. This includes using cleaner environmental practices during coffee processing, such as introducing composting of coffee cherry pulp. Kalisa also helps disseminate integrated health and coffee messages through a weekly coffee talk-show produced by the National University of Rwanda’s Radio Salus, called Imbere Heza (“Bright Future”). In one show, for example, a man explained to a fellow farmer that to get good coffee cherries, he should thin his trees to renew his plantation.

Integrating Healthy Lives

Kalisa has also helped the SPREAD project’s health team deliver integrated messages on family planning, maternal and child health, alcohol, nutrition, gender issues, and the linkages between these. He uses examples such as the one about tree thinning to explain that families that space their children tend to be healthier, as they can plan the number of children to better fit with the financial and natural resources at hand.

Kalisa sees the benefits of using community agents to deliver integrated health, environment, and livelihood messages. This includes training extension agents to discuss environmental and human health issues in the context of coffee growing. Also, having coordinators from the coffee program and the health program go hand-in-hand to the field saves time, fuel, and other project costs. Kalisa believes that this campaign to educate coffee farmers and their families on the linkages between human health, a healthy environment, and strong livelihoods will lead to long-term change in their behavior, attitudes, and knowledge – change that will help them live better lives today and into the future.

This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project. A PDF version can be downloaded from the PHE Toolkit. PHE Champion profiles highlight people working on the ground to improve health and conservation in areas where biodiversity is critically endangered.

Photo Credit: “Rwanda photos 060,” courtesy of David Dewitt/counterculturecoffee. -

STATcompiler: Visualizing Population and Health Trends

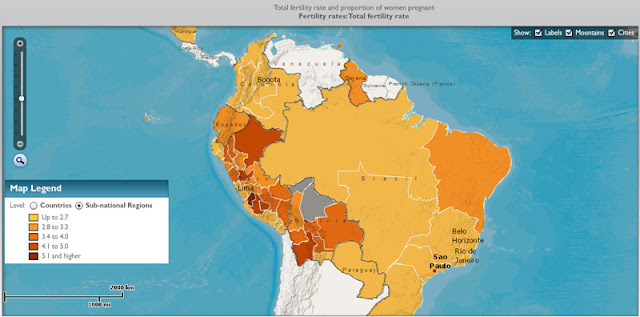

›World population is growing – earlier this week, the global community symbolically marked the arrival of the seven billionth person. But the unprecedented growth in global population over the last few decades has not affected everyone equally – in 1950, 68 percent of the world’s population lived in developing regions; today that number is 82 percent. MEASURE’s latest version of their STATcompiler tool helps visually highlight areas simultaneously experiencing the most demographic change and poor health indicators.

The revised STATcompiler – released in September – provides new ways for users to visualize data by generating custom data tables, line graphs, column charts, maps, and scatter plots based on demographic and health indicators for more than 70 countries. Users can select countries or regions of interest, and relevant indicators, including for family planning, fertility, infant mortality, and nutrition. Tables can be further customized to view indicators over time, across countries, and by background characteristics, such as rural or urban residence, household wealth, or education. In some cases, sub-national data is available. User-created tables and images are then exportable so that they may be easily used in papers or presentations.

Since STATcompiler is still in active development, certain functions are still being added. HIV data has not yet been integrated into the program, nor has the express viewer function, with customizable, ready-made tables for quick access. Additionally, updated information is not available for all countries, in all categories – for instance, the most recent data available for Mexico comes from a 1987 survey. If preferred, the legacy version remains available to users in the meantime.

MEASURE DHS – the Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results Demographic and Health Surveys project – provides technical assistance for data collection on health and population trends in developing countries. Their demographic and health surveys, funded by USAID, provide data for a wide range of monitoring and impact evaluation indicators at the household level in the areas of population, health, and nutrition. They have become a staple data source for researchers, and the addition of better analysis functions and dissemination tools, via STATcompiler, will hopefully help advance understanding of demographic and health trends.

Image Credit: Map from STATcompiler, arranged by Schuyler Null. -

New Report Launched: ‘The World’s Water’, Volume Seven

›“The water problem is real and it is bad,” said MacArthur “Genius” Fellow and founder of the Pacific Institute Peter Gleick at the October 18 launch of the seventh volume the institute’s biennial report on freshwater resources. “It’s not bad everywhere, and it’s not bad in the same way from place to place, but we are not doing what we need to do to address all of the different challenges around water.”

“The World’s Biggest Problem”

Worldwide, more than a billion people lack access to safe drinking water, while two and a half billion lack access to adequate sanitation services. “This is the world’s biggest water problem,” said Gleick, “the failure to meet basic human needs for water – it’s inexcusable.”

Gleick predicts that the world will fail to meet the Millennium Development Goals for water and sanitation by 2015, and noted that measures of illness for water-related diseases are rising, rather than falling.The World’s Water series provides an integrated way of thinking about water by exploring major concepts, important data trends, and case studies that point to policies and strategies for sustainable use of water. Volume seven includes chapters on climate change and transboundary waters, corporate water management, water quality challenges, Australia’s drought, and Chinese and U.S. water policy. The new volume also includes a set of side briefs on the Great Lakes water agreement, the energy required to produce bottled water, and water in the movies, as well as 19 new and updated data tables. An updated water conflict chronology looks at conflicts over access to water, attacks on water, and water used as a weapon during conflict.Peter Gleick on climate change and the water cycle.

Despite the added data, Gleick said that vast gaps remain in our knowledge and understanding about water. We lack accurate information on how much water the world has, where it is, how much humans use, and how much ecosystems need, he said. “So right off the bat, we are at a disadvantage.”

Focus on Efficiency, Infrastructure to Better Manage Water

One of the major concepts that has connected various volumes of The World’s Water is the concept of a “soft path for water” – a strategy for moving towards a more sustainable future for water through several key focus points: improved efficiency, decentralized infrastructure, and broadly rethinking water usage and supply.

Other cross-cutting themes include climate and water, peak water, environmental security, and the human right to water (formally recognized in a 2010 UN General Assembly resolution). “I would argue that all of these combined offer to some degree a different way of thinking about water, an integrated way of thinking about water,” Gleick said.

The China Issue

The role of China has been one of the most significant changes over the course of the series, said Gleick. The growth in the Chinese economy has led to a massive growth in demand for water (see the Wilson Center/Circle of Blue project, Choke Point: China), as well as massive contamination problems. The newest volume addresses these issues as well as China’s dam policies – internally, with neighboring countries, and around the world.

Gleick pointed out that China is one of the only nations (maybe the only) that still has a massive dam construction policy, and their installed capacity is already much larger than the United States, Brazil, or Canada. In addition, Chinese companies and financial interests are involved in at least 220 major dam projects in 50 countries around world. These projects have become increasingly controversial, for both environmental and political reasons, he said.

“My lens is typically a water lens,” Gleick said, but “none of us can think about the problems we really care about, unless we think about a more integrated approach.” Gleick emphasized the need for new thinking about sustainable, scalable, and socially responsible solutions. “We have to do more than we are doing, in every aspect of water,” he concluded.

Event Resources

Photo Credit: “Water,” courtesy of flickr user cheesy42. -

Top 10 Posts for October 2011

›October brought plenty of talk about population – the UN estimates that the seven billionth person alive today was born on the 31st and that brought a flurry of media coverage from all corners. Elizabeth Leahy Madsen broke down how we got to that number and where we’re going. Peter Gleick explained “peak water,” Jon Foley impressed at the first South by Southwest Eco conference, and we highlighted some of the debate around Solomon Hsiang et al.’s article about El Niño and conflict. Here are the top 10, measured by unique pageviews:

1. How Did We Arrive at 7 Billion – and Where Do We Go From Here?

2. Jon Foley: How to Feed Nine Billion and Keep the Planet Too

3. India’s Maoists: South Asia’s “Other” Insurgency

4. Tunisia’s Shot at Democracy: What Demographics and Recent History Tell Us

5. Weathering Change: New Film Links Climate Adaptation and Family Planning

6. El Niño, Conflict, and Environmental Determinism: Assessing Climate’s Links to Instability

7. Watch: Peter Gleick on Peak Water

8. Peter Gleick: Population Dynamics Key to Sustainable Water Solutions

9. In Search of a New Security Narrative: The National Conversation Series Launches at the Wilson Center

10. Food Security and Conflict Done Badly…, via Edward Carr, Open the Echo Chamber

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.