-

Roger-Mark De Souza, Climate and Development Knowledge Network

Population-Climate Dynamics: From Planet Under Pressure to Rio

›May 11, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Roger-Mark De Souza, appeared on the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN).

In late May, I presented research on population and climate dynamics in hotspots at the Planet Under Pressure conference in London, in a session organized by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network. As we prepare for the Rio+20 Earth Summit in June, I reflect on the roles of population dynamics and climate-compatible development for ensuring a future where we can increase the resilience of the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.- Improving our well-being and the future we can have is within our reach: We can take action to improve well-being through specific actions that can produce short term results. This is a key message encapsulated in the concept of climate-compatible development, reflected in many presentations and discussions that I heard at Planet Under Pressure. Even though others were not calling it “climate-compatible development,” the essence and the meaning behind the research was the same – small concrete discrete steps are possible, and taking action on population dynamics is one of them.

- Population is on the agenda: Population issues – growth, density, distribution, aging, gender – were a constant at Planet Under Pressure – and in more ways than just looking at population as a driver. It is clear that there is interest, and a need, to address population as a key component of climate-compatible development.

- But those concerns and issues must be location specific, and must be contextualized for the policy and programmatic environment: Population issues must be framed in the appropriate context – and must move beyond academic exploration. I attended one session where a paper presented an academic supposition of whether we should invest in consumption versus fertility reduction to produce short-term returns for climate, but the analysis was completely devoid of any political, policy, or programmatic truth-testing. We must factor in those considerations when making recommendations, if ultimately we are really looking to make the difference that we can.

Photo Credit: “Urbanization in Asia,” courtesy of United Nations Photo. -

Michael Kugelman, AfPak Channel

Pakistan’s Climate Change Challenge

›May 11, 2012 // By Wilson Center Staff

Last month, an avalanche on the Siachen glacier in Kashmir killed 124 Pakistani soldiers and 11 civilians. The tragedy has intensified debate about the logic of stationing Pakistani and Indian troops on such inhospitable terrain. And it has also brought attention to Pakistan’s environmental insecurity.

Siachen is rife with glacial melt; one study concludes the icy peak has retreated nearly two kilometers in less than 20 years. It has also been described as “the world’s highest waste dump.” Much of this waste-generated from soldiers’ food, fuel, and equipment-eventually finds its way to the Indus River Basin, Pakistan’s chief water source.

Siachen, in fact, serves as a microcosm of Pakistan’s environmental troubles. The nation experiences record-breaking temperatures, torrential rains (nearly 60 percent of Pakistan’s annual rainfall comes from monsoons), drought, and glacial melt (Pakistan’s United Nations representative, Hussain Haroon, contends that glacial recession on Pakistani mountains has increased by 23 percent over the past decade). Experts estimate that about a quarter of Pakistan’s land area and half of its population are vulnerable to climate change-related disasters, and several weeks ago Sindh’s environment minister said that millions of people across the province face “acute environmental threats.”

Continue reading on the AfPak Channel.

Sources: Daily Times, Dawn.com, Environment News Service, The Express Tribune, The New York Times, Remote Sensing Technology Center of Japan.

Photo Credit: “Surveying damage in Pakistan,” courtesy of the U.S. Army.

-

A Northern View: Canada’s Climate Claims and Obligations

›Reneging on Kyoto, Keystone pipeline drama, pain at the pump, re-aligned Arctic sovereignty, melting outdoor hockey rinks – all these aspects of climate change are being discussed in Canada.

However, Canadians, as potential citizens of the next energy superpower, need a more comprehensive and enriching debate. Climate change adaptation measures, at home and abroad, are inevitable, but the issue has largely been ignored by the federal government thus far.

To many Americans, it may seem that Canada has equated energy production with national prosperity, but Canadians are increasingly concerned about the human security and eco-justice implications of ongoing climate change as well. Lack of leadership at the federal level on Kyoto-related energy efficiency and emissions mitigation has been partially offset by actions at the provincial and municipal levels, but climate change is occurring now and it demands a coordinated response from the federal government, the only political apparatus capable of channeling the resources necessary for making a solid contribution to global climate change adaptation.

A moderate predictive scenario suggests that the regional impacts of climate change will be very expensive: the UN projects the global Green Climate Fund will require up to $100 billion a year by 2020. Water stress – too little, too much, or the perception of either – may be the most common theme. Coastal flooding, shoreline erosion, glacier retreat, chronic water shortages, loss of biodiversity and habitat, increased spread of invasive species, extreme weather events; taking preventive action against these (beyond the obvious call for reduced emissions) will be prohibitively expensive for most communities around the globe, including the coastal and northern regions of Canada.

The UN Convention to Combat Desertification has become a conduit for the argument that drought and land degradation related to climate change justifies southern demands for northern investment in initiatives in Africa and elsewhere. As a high emissions per capita nation, Canada has an obligation to contribute to such international efforts.

But I also don’t see why the indigenous peoples of the circumpolar north should be denied claims as permafrost thaws and ice-cover vital for subsistence hunting disappears. Citizens of small island states, to whom adaptation may well mean the abandonment of their homeland, have charged willful ignorance or purposeful negligence of their plight; so too might riparian communities along Canada’s many ocean shorelines, lakes, and rivers. Farmers, fishers, First Nations communities: all will need to adapt. We need to start seriously planning ahead to meet climate change scenarios, instead of burying the issue under the tar sands.

Of course, people will adapt to shifting conditions; such is the imperative of survival. And there are many ingenious ways this will materialize. Indeed many mitigation and adaptation strategies blend together as hybrids today. Building more effective alternative energy systems can be seen as much as responses to climate change as preventive measures and involve both public and private sector funding, for example.

However, paying for adaptation is another matter, and here it is vital in my view to stress the potential role of infrastructure spending by the federal government. Much of Canada’s current fiscal restraint is indeed a welcome development if the government cuts back on waste and redundancy, but not if it serves as a veil for sacrificing principles of eco-justice – the idea that those who made the least contributions to and benefit the least from environmental problems should not bear disproportionately higher risks.

Of course there will be nasty disputes ahead about the accounting, accountability, legitimacy, and purpose of climate change adaptation funding for Canada, in or out of the UNFCCC process, but let me draw just a few general conclusions at this stage:- There is an ethical imperative to contribute to international adaptation funding, perhaps just as great an imperative as traditional efforts to help former colonized countries. It’s not just about money, at least not directly: Canadian technical, policy, and financial expertise should be harnessed for this purpose as well.

- Unlike in other policy areas, there is no way to unload or pass the buck on climate change adaptation efforts: they demand the utilization of centralized resources redistributed throughout the country and through multilateral funding mechanisms.

- Adaptation funding should not, however, supplant more traditional emergency, humanitarian, or environmental funding. It should be seen as a supplement, albeit one with increasing importance, but not as a new form of dependency or gold-rush of aid-with-obligations opportunities. The current government is right to worry about accountability issues.

- But accountability goes both ways: we need at least to get the accounting and communications right on this, thus the need for open dialogue and ongoing consultation. Killing the well-respected National Roundtable on the Environment and the Economy, which consulted various Canadian stakeholders on key environmental questions, was not a good start.

Peter Stoett is the Fulbright Research Chair in Canada-U.S. Relations at the Wilson Center’s Canada Institute and professor in the Department of Political Science at Concordia University, Montreal.

Sources: CBC, The Catholic Register, The Huffington Post, International Institute for Sustainable Development, UNFCCC.

Photo Credit: “City, Suburb, Ocean, Mountain,” courtesy of flickr user ecstaticist (Evan Leeson). -

Learning From Success: Ministers of Health Discuss Accelerating Progress in Maternal Survival

›“The gains we have made [in reducing maternal mortality rates] are remarkable; however, gains are fragile and donor resources are declining. Substantial investments must be maintained to safeguard these hard-wins,” said Afghan Minister of Health Suraya Dail at the Wilson Center on April 23. [Video Below]

As part of the Wilson Center’s Global Health Initiative, the Advancing Dialogue to Improve Maternal Health series partnered with the U.S. Agency for International Development to co-host Minister Dail, along with Honorable Dr. Mam Bunheng, Minister of Health, Cambodia; Honorable Dr. Bautista Rojas Gómez, Minister of Health, Dominican Republic; and Dr. Fidele Ngabo, Director of Maternal and Child Health, Ministry of Health, Rwanda.

These ministers spoke about the lessons learned in countries where there has been tremendous progress under challenging circumstances.

In the Dominican Republic, Bautista Rojas Gomez said the first challenge was to address the “Dominican paradox,” where maternal mortality rates were high despite the fact that 97 percent of women received prenatal care and delivered in hospitals. The government created a zero tolerance policy that included a comprehensive surveillance system, mandatory maternal death audits, and community oversight of services, which assured better quality services.

Similar political commitment improved indicators in Cambodia, where maternal mortality rates dropped from 472 to 206 per year from 2005 to 2010. “It takes a village…and the prime minister has inspired the country to act,” said Mam Bunheng. Through increased access to contraception the number of children per woman went from seven to three and commitment to family planning, education, technology, infrastructure, and community have been the key drivers of success.

“In Rwanda, the big challenge we are having is education,” said Fidele Ngabo. “Many of the maternal health indicators depend on education.” When women and girls are educated they are twice as likely to utilize modern contraception. The efforts of Rwanda’s government have been instrumental in facilitating positive change, he said, particularly the efforts of First Lady Jeannette Kagame, who he called a “champion” for women and girl’s health.

As witnessed throughout the Advancing Dialogue to Improve Maternal Health series – and reiterated by the ministers of health – the interventions to improve maternal mortality rates exist, what’s left is to generate the needed political willpower.

Event Resources

Photo Credit: David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

New Surveys Generate Mixed Demographic Signals for East and Southern Africa

›May 8, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy Madsen

The pace of fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa will be the single most important factor in whether the global population reaches the UN’s high projection of nearly 11 billion in 2050, or remains closer to the low projection of 8 billion. In recent years, the high projection has seemed more likely, as sub-Saharan Africa has been marked by stalled fertility declines and stagnant rates of contraceptive use. Survey results released over the past year showing dramatic increases in contraceptive use in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda therefore set demographers and the family planning community abuzz, signaling that concerted efforts to improve health services had paid off and fertility rates were on the decline. But in recent months, additional surveys from Mozambique, Uganda, and Zimbabwe have shown that those positive trends are not universal.

-

Carl Haub, Behind the Numbers

Bangladesh 2011 Demographic and Health Survey Shows Continued Fertility Decline, Improved Health Indicators

›May 7, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Carl Haub, appeared on the Population Reference Bureau’s Behind the Numbers blog.

The Bangladesh 2011 Demographic and Health Survey is the ninth demographic survey taken in the country since 1975. Except for a few very small countries and city-states, Bangladesh is the world’s most densely populated country with about 1,100 people per sq. kilometer. The country’s area is about the same as the U.S. state of Arkansas and a bit more than Greece but is home to over 150 million people.

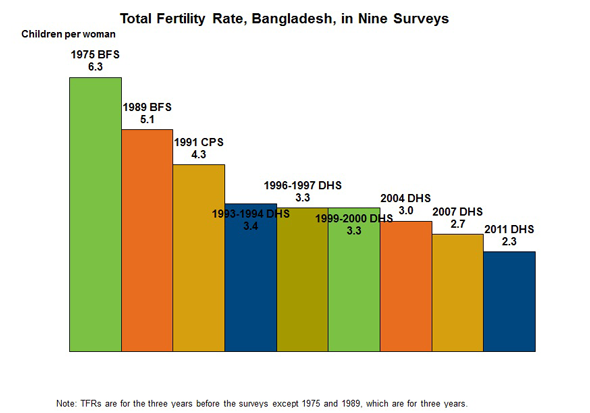

The preliminary 2011 report has just been released and it shows that fertility has continued its decline to a low level. The total fertility rate (TFR) for the three-year period before the survey was 2.3 – 2.0 in urban areas and 2.5 in rural areas. The survey interviewed 17,842 ever-married women ages 12 to 49 and 3,997 ever-married men ages 15 to 54 from July to December 2011. Rural women accounted for two-thirds of those interviewed. From 1975 to 1994, the TFR in Bangladesh was in continuous decline. But the next three surveys showed a tendency for TFR decline to “stall” at a medium level (see graph). Desired family size has greatly decreased. In the survey, 76.2 percent of women with two living children said that they did not wish to have any more children, an additional 5.3 percent had been sterilized, and 1.3 percent said they were incapable of conceiving.

In the survey, 61.2 percent of currently married women said that they were using some form of family planning, a level comparable to developed countries. The use of modern methods was quite high at 52.1 percent. Unlike neighboring India, where female sterilization predominates, the contraceptive pill is the most widely used modern method at 27.2 percent, followed by injectables (11.2 percent), and the male condom (5.5 percent). Contraceptive use has risen steadily in surveys, up from 7.7 percent in 1975. Family planning use has risen despite the fact that fewer women report a visit from a family planning worker, either government or private. Overall, only 15.5 percent reported contact with a home visitor, which has been an important part of the country’s family planning program. The report notes that this may be due to workers deciding to provide services from community clinics for three days a week.

Continue reading on Behind the Numbers.

Sources: MEASURE DHS.

Imaged Credit: Carl Haub/Behind the Numbers. -

The Future of South Asian Security: Prospects for a Nontraditional Regional Architecture?

›May 7, 2012 // By Kate Diamond“The nontraditional security threats of tomorrow could themselves become sources of future traditional conflict if they’re not effectively addressed today,” said Mahin Karim, the senior associate for political and security affairs at The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). Karim spoke during an April 11 policy briefing on nontraditional security threats in South Asia, hosted by the Wilson Center.

“The nature of nontraditional security challenges faced by South Asia may offer opportunities to change the security agenda, perhaps even subsuming traditional security concerns in the region,” she added.

Karim, along with Roy Kamphausen, Dennis Pirages, Mallika Joseph, Amal Jayawardane, Tariq Karim, and Richard Matthew, presented findings from a three-year NBR project that assessed potential threats to the region through 2025, possible policy responses, and the feasibility of implementing those responses at the national, sub-regional, and regional levels.

In looking at the potential for environmental, population, health, resource, and demographic challenges to threaten security within the region, Karim said several trends became evident across the three workshops and five reports the project produced: the growing impact of nontraditional threats on security; the potential for the region to benefit from a demographic dividend; the growing opportunities for collaboration afforded by increasing media and technological connectivity; India’s own rise as a regional and global power; and the need to examine new and alternate options for sub-regional cooperation.

A Blurring Line Between Traditional and Nontraditional Threats

The growing importance of nontraditional threats is already apparent in India, said Mallika Joseph, the executive director for the Colombo-based Regional Centre for Strategic Studies.

“Many of the challenges which we have grown up understanding as nontraditional security challenges have now migrated and are being termed as traditional security threats, and the line dividing them continues to blur,” said Joseph.

Poor governance and resource management has exacerbated economic inequalities, which are “ever-increasing, despite sustained economic growth,” said Joseph. Meanwhile, more connectivity between different regions and classes in the country has created “greater expectations, worse disappointments, and social unrest.” That unrest has been most visible in the country’s Naxalite insurgency, where years of superficial policy “address[ing] the symptom, rather than the disease itself,” means that “what was earlier a deficit of human security has morphed itself into a situation where the state now faces a security deficit.”

As India’s policymakers attempt to minimize economic inequalities, they must do so against the backdrop of a rapidly growing population. Between now and 2025, population growth in India will account for one-fifth of growth worldwide, said Joseph. While “population trends by themselves are neither inherently good or bad, they do create conditions for peace or conflict within which states must respond.”

“Demography Is a Multiplier”

The region’s changing demographics will also impact its ability to mitigate future security threats. “Demography is a multiplier,” said Joseph. “If a state has weak governance, demography can exacerbate conditions for instability.”

Sri Lanka’s recent history is a testament to this. The country’s youth “played a very important role” in the three major insurgencies that plagued the country since the 1970s, said Amal Jayawardane, an international relations professor at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Today, although the government provides free education up to the university level, youth are hampered by a disproportionately high rate of unemployment – 19 percent compared to a national average of 4.2 percent, according to the latest government labor force report. Investment in workforce opportunities for youth, along with “institutional reforms like good governance, transparency, and … eradicat[ing] corruption” will have to be considered in order to minimize the potential for youth-driven instability in the future, Jayawardane said.

Messy Boundaries, Messy Threats

“I think that one of the things that this project revealed is that we don’t have a simple definition of what constitutes South Asia per se,” said University of California, Irvine’s Richard Matthew. “It’s an interesting idea, but there’s disagreement over its actual boundaries. And it’s not clear that however we define the boundaries, they align perfectly with the threats. So the threats are messy and the boundaries of South Asia are messy.”

Many of the nontraditional threats facing the region are transnational in nature – glacial melt in the Himalayas affects water supply throughout the region, for example. Those cross-border issues merit a cross-border response.

“It isn’t like there’s a uniform response that would work for China and India and Pakistan on water security,” said Matthew. “We could and we ought to start experimenting with systems that we have reason to believe might be useful, moving them out of their national containers and into regional settings, like REDD and REDD+ and Payment for Ecosystem Services.”

Transnational Solutions for Transnational Problems

Along these lines, Mahin Karim said that the region’s youth are uniquely positioned to foster new and different ways of thinking about public policy. “The region’s youth bulge, particularly in the context of an emerging or next generation of policymakers, offers opportunities for new thinking on traditional security issues that are unhampered by the baggage of history,” she said. “Perhaps we might have a generation that’s more willing to engage multilaterally than previous or current generations have demonstrated to have been.”

Tariq Karim, Bangladesh’s high commissioner to India, said his country will depend on exactly that kind of multilateral cooperation in the coming years.

“I look at the map, I look at where Bangladesh is situated, and I can’t escape my geography,” he said. “My geography compels me to keep looking at that map and see how we can resolve our issues. On our own, it’s not possible – it’s just not possible.”

Event ResourcesSources: Sri Lanka Department of Census and Statistics.

Photo Credit: David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

Taming Hunger in Ethiopia: The Role of Population Dynamics

›May 4, 2012 // By Laurie Mazur

Ethiopia has been deemed a population-climate “hotspot” – a place where rapid growth and a changing climate pose grave threats to food security and human well-being.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.