-

Book Preview: In ‘War and Conflict in Africa’, GWU Scholar Skeptical That Natural Resources Play a Leading Role

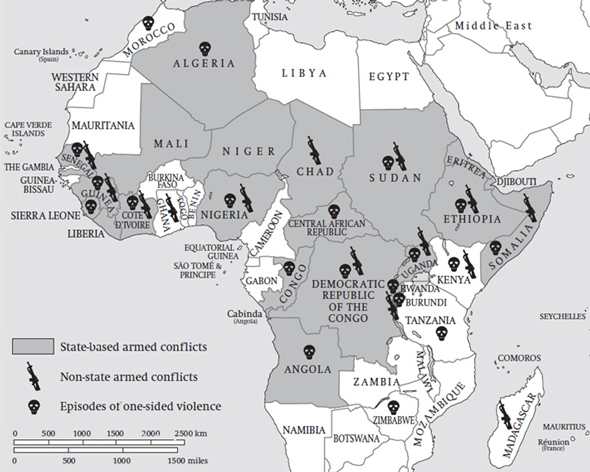

›November 30, 2011 // By Elizabeth Leahy MadsenWhile there is widespread agreement that the incidence of conflict in Africa is high, scholars and development agencies alike debate its driving forces and how to move toward solutions. Paul Williams, associate professor in the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and collaborator with the Wilson Center’s Africa Program, recently published a book that aims to both quantify African conflicts and devise a framework of their causes. In War and Conflict in Africa, Williams evaluates which factors explain the frequency of conflict in Africa during the post-Cold War era and how the international community has tried to build peace and prevent future conflict.

Although there have been promising trends toward establishing peace and democracy in some African countries, the continent still accounts for about one-third of all armed conflicts annually – more than Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas combined. International responses to these events range from focused humanitarian and conflict resolution efforts, to new regional organizations and global strategic and defense partnerships.

Seven of the 16 current UN peacekeeping missions operate in Africa, more than any other continent. The UK government has elected to spend nearly one-third of its development assistance in conflict-affected areas, and more than half of its “focus” countries are in Africa. In 2008, the Department of Defense created the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), whose commander, General Carter Ham, in a speech to Congress earlier this year, described “an insidious cycle of instability, conflict, environmental degradation, and disease that erodes confidence in national institutions and governing capacity,” as motivation for American military attention. “This in turn often creates the conditions for the emergence of a wide range of transnational security threats,” he said.

Evaluating the Ingredients of Conflict

Williams rejects earlier theses that attribute conflict across the continent to a single factor, such as the boundary legacies of colonialism, greed, or ethnicity. Instead, he characterizes African conflicts as “recipes” composed of case-specific mixes of factors, many of which are underlying and only some of which are sufficient triggers for conflict. “Collier is wrong,” Williams explained in an email interview. “Governance structures are always an important part of the buildup to war.”

Five “ingredients” of conflict are examined in-depth: neo-patrimonial governance structures; natural and human resources; sovereignty and self-determination; ethnicity; and religion. Among these, the book presents a fairly skeptical view of resources, ethnicity, and religion as immediate drivers of conflict. This assessment that environmental and identity issues are not sufficient to generate conflict on their own aligns with the book’s overarching argument: The decisions of political actors can instigate conflict or motivate peace from virtually any context, manipulating factors such as ethnicity and religion for their own advantage.

Effects of Natural Resources Are “Open-Ended”

A widely publicized thread of peace and conflict studies posits that resources, either when scarce or abundant, have an important role in triggering wars. A 2009 UN Environment Programme report found that 40 percent of all internal conflicts since 1950 “have a link to natural resources.” Recent peer-reviewed research has suggested that certain environmental changes increase the likelihood of civil conflicts or are directly responsible for it. Yet the question remains a source of much debate. For his part, Williams asserts that natural resources alone are insufficient to cause conflict.

War and Conflict in Africa presents several reasons that researchers and policymakers should avoid linking resources directly to conflict without considering the influence of intervening factors. Chief among them is that the value of any resource is socially constructed – no stone or river carries worth until humans decide so. Therefore, Williams argues that “it is political systems, not resources per se, that are the crucial factor in elevating the risk of armed conflict.”

The book suggests that two extant theories successfully demonstrate the connection between resources and conflict. The first body of research finds that conflict is more likely in regions that face a combination of resource abundance and a high degree of social deprivation. The second theory suggests that the link between resources and conflict lies in bad governance, whether exploitative or unstable. Both theories have explanatory power for Williams’s central line of thinking: Resources can be either a blessing or a curse, depending on leadership.

“Inserted into a context where corrupt autocrats have the advantage, resources will strengthen their hand and generate grievances,” he writes (p. 93). “Inserted into a stable democratic system, they will enhance the opportunities for leaders to promote national prosperity.”

Population and the Environment

Williams does accede that particular resource factors – land and demography, for example – may play a more significant role than others in conflict, but calls for more research. In a brief discussion of population age structure, the book suggests that there is no single relationship between demography and conflict but multiple ways that the two can relate. Williams mentions the theory that “large pools of disaffected youth” with few opportunities can raise the risk of volatility. However, he then notes other research showing that the most marginalized members of certain African societies are less likely to participate in political protests and more likely to tolerate authoritarian rule than those who are better off.

“The most marginalized from society are the truly destitute without patrons and suffering from severe poverty. They may well be inclined to join an insurgency movement once it begins to snowball but they will not usually play a key role in establishing the rebel group in the first place,” Williams said. However, “any time there are large pools of poor and unemployed youth there is the potential for leaders to manipulate them.”

On environmental resources, the book argues that land should be a central feature of quantitative research on the relationship between resources and conflict. Most African economies continue to rely on agriculture, and Williams observes that land has been “at the heart” of many conflicts in the region through a variety of governance-related mechanisms relating to its management and control. He places less emphasis on water scarcity as a potential factor in conflict, noting that the 145 water-related treaties signed around the world in the past decade auger well for cooperation rather than competition.

Williams is also dubious of emerging arguments that climate change could directly increase the incidence of conflict, either through changing weather patterns or climate-induced migration.

“Because armed conflicts are, by definition, the result of groups choosing to fight one another, any process, including climate change, can never be a sufficient condition for armed conflict to occur,” he argued. “Armed conflicts result from the conscious decisions of actors which might be informed by the weather but are never simply caused by it.”

No Simple Formula

Williams is not the only observer to find the narrative that resource shortage (or abundance) precipitates conflict too simplistic. His message to policymakers is a common refrain from academics and analysts seeking to counteract policymakers’ quest for simple formulas: We need more data.

“When deciding how to spend our money, we need to spend more of it on developing systems which deliver accurate knowledge about what is happening on the ground, often in very localized settings,” Williams said. War and Conflict in Africa contributes to a more complex understanding of the political actors and systems that catalyze or prevent conflict and offers a cautionary tale to those who seek only proven, easy predictions.

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and senior technical advisor at Futures Group. She was previously a senior research associate at Population Action International. Full disclosure: She was a graduate student of Paul Williams’ in 2007.

Sources: DFID, Englebert and Ron (2004), Ham (2011), Hsiang et al (2011), Kahl (1998), Leysens (2006),Østby et al (2009), Radelet (2010), Themnér and Wallensteen (2011), UNEP (2009), UN Peacekeeping, Williams (2011)

Image Credit: Conflicts in Africa 2000-09, reprinted with permission courtesy of P.D. Williams, War and Conflict in Africa (Williams, 2011), p.3. -

UNiTE To End Violence Against Women

›November 25, 2011 // By Schuyler NullToday is the International Day to End Violence Against Women, an awareness and advocacy campaign organized by a host of UN agencies and offices “to galvanize action across the UN system to prevent and punish violence against women.”

Gender equity and inequity play a role in a myriad of international development, health, security, and even environmental issues, from rape as a weapon of war; demography’s effects on political stability; maternal health and its impact on child development; women’s rights as a social stability issue; and the disproportionate effect of climate change on rural women.

The numbers around gender-based violence are staggering. According to the UN:

Here are some of New Security Beat’s posts on gender-based violence and inequity and their intersection with development, the environment, and security:- 70 percent of women experience physical or sexual violence from men in their lifetime.

- Approximately 250,000 to 500,000 women and girls were raped in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), at least 200,000 cases of sexual violence, mostly involving women and girls, have been documented since 1996, though the actual numbers are considered to be much higher.

- In the United States, one-third of women murdered each year are killed by intimate partners; in South Africa, a woman is killed every six hours by an intimate partner; in India, 22 women were killed each day in dowry-related murders in 2007; and in Guatemala, two women are murdered, on average, each day.

- Over 60 million girls worldwide are child brides, married before the age of 18, primarily in South Asia (31.1 million) and sub-Saharan Africa (14.1 million).

Gender-Based Violence in the DRC: Research Findings and Programmatic Implications:

Dr. Lynn Lawry, senior health stability and humanitarian assistance specialist at the U.S. Department of Defense, presented findings from the first cross-sectional, randomized cluster study on gender-based violence in the DRC at the Wilson Center this year. The first of its kind in the region, the population-based, quantitative study covered three districts in the DRC and a total of 5.2 million adults, comprehensively assessing gender-based violence, including its prevalence, circumstances, perpetrators, and physical and mental health impacts.

Pop Audio: Judith Bruce on Empowering Adolescent Girls in Post-Earthquake Haiti: “The most striking thing about post-conflict and post-disaster environments is that what lurks there is also this extraordinary opportunity,” said Judith Bruce, a senior associate and policy analyst with the Population Council. Bruce spent time last year working with the Haiti Adolescent Girls Network, a coalition of humanitarian groups conducting workshops focused on the educational, health, and security needs of the country’s vulnerable female youth population.

The Walk to Water in Conflict-Affected Areas: Constituting a majority of the world’s poor and at the same time bearing responsibility for half the world’s food production and most family health and nutrition needs, women and girls regularly bear the burden of procuring water for multiple household and agricultural uses. When water is not readily accessible, they become a highly vulnerable group. Where access to water is limited, the walk to water is too often accompanied by the threat of attack and violence.

Weathering Change: New Film Links Climate Adaptation and Family Planning: “Our planet is changing. Our population is growing. Each one of us is impacting the environment…but not equally. Each one of us will be affected…but not equally,” asserts the new documentary, Weathering Change, launched at the Wilson Center in September. The film, produced by Population Action International, explores the devastating impacts of climate change on the lives of women in developing countries through personal stories from Ethiopia, Nepal, and Peru.

Sajeda Amin on Population Growth, Urbanization, and Gender Rights in Bangladesh:

The Population Council’s Sajeda Amin describes the Growing Up Safe and Healthy (SAFE) project, launched in Dhaka and other Bangladeshi cities last. The initiative aims, to increase access to reproductive healthcare services for adolescent girls and young women, bolstering social services to protect those populations from (and offer treatment for) gender-based violence, and strengthen laws designed to reduce the prevalence of child marriage – a long-standing Bangladeshi institution that keeps population growth rates high while denying many young women the opportunity to pursue economic and educational advancement.

No Peace Without Women: On October 31, 2000, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325, which called for women’s equal participation in all efforts to maintain and promote peace and security; however, little progress has been made over these last 10 years and women remain on the periphery when it comes to post-conflict reconstruction and development. A report from the humanitarian organization CARE concedes that “much of the action remains declarative rather than operational.”

Addressing Gender-Based Violence to Curb HIV: At last year’s International AIDS Conference in Vienna an astonishing development in the campaign to stem the spread of HIV/AIDS was unveiled – a microbicide with the ability to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV. This welcome development coincides with an intensified focus on women’s health and security needs among donors, especially the United States.

The Future of Women in the MENA Region: A Tunisian and Egyptian Perspective: Lilia Labidi, minister of women’s affairs for the Republic of Tunisia and former Wilson Center fellow, joined Moushira Khattab, former minister of family and population for Egypt, this summer at the Wilson Center to discuss the role and expectations of women in the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions, as well as issues to consider as these two countries move forward.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s Office. -

7 Billion: Reporting on Population and the Environment

› “It’s an issue – population – that is immensely diverse in its effects and repercussions, and it’s a great opportunity for reporting,” said Jon Sawyer, executive director of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting at a November 1 roundtable discussion at the Wilson Center. The session, reporting on population and the environment connections, also featured Dennis Dimick, executive environment editor at National Geographic; Kate Sheppard, environment reporter for Mother Jones; and Heather D’Agnes, foreign service environment officer at USAID.

“It’s an issue – population – that is immensely diverse in its effects and repercussions, and it’s a great opportunity for reporting,” said Jon Sawyer, executive director of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting at a November 1 roundtable discussion at the Wilson Center. The session, reporting on population and the environment connections, also featured Dennis Dimick, executive environment editor at National Geographic; Kate Sheppard, environment reporter for Mother Jones; and Heather D’Agnes, foreign service environment officer at USAID.

“It’s an issue – population – that is immensely diverse in its effects and repercussions, and it’s a great opportunity for reporting,” said Jon Sawyer, executive director of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting at a November 1 roundtable discussion at the Wilson Center. The session, reporting on population and the environment connections, also featured Dennis Dimick, executive environment editor at National Geographic; Kate Sheppard, environment reporter for Mother Jones; and Heather D’Agnes, foreign service environment officer at USAID.The PBS NewsHour segment on “seven billion” featuring collaboration with the Pulitzer Center and National Geographic.

A Cumulative Discussion

“I ended up covering reproductive rights and health issues because I saw a need and a gap in coverage,” said Kate Sheppard. “I had been an environmental reporter for years…and so it sort of became this add-on beat for me.” But, she emphasized, they are actually very related issues.

“It’s a cumulative discussion,” said Dennis Dimick, speaking about National Geographic’s “7 Billion” series this year. “[Population] really hasn’t been addressed that much in media coverage over the past 30 years, in this country at least, and I think that the idea was that it wasn’t really just a discussion about the number seven billion, which is a convenient endline and easy way to get into something, but really to talk about the meaning of it, and the challenges and the opportunities that means for us as a civilization living on this planet.”

The series has had stories on ocean acidification, genetic diversity of food crops, the transition to a more urban world, as well as case studies from Brazil, Africa’s Rift Valley, and Bangladesh. “What we are trying to do in this series is really paint a broad picture to try to unpack all these issues and try to come at this question in sort of broad strokes,” Dimick said. “It’s sort of like we are orchestrating a symphony. Even though it’s a printed magazine, it’s a multimedia project – more than just words and more than just pictures.”

Collaborative Reporting

The Pulitzer Center, a non-profit journalism organization that seeks to fill gaps in coverage of important systemic issues, was able to commission pieces for PBS NewsHour that complemented the National Geographic series. This population collaboration launched the Center’s own initiative on population. “Our hope was that by having that platform, and the visibility of National Geographic and NewsHour, that it would bring attention to the rest of our work,” Sawyer said. The Pulitzer Center has gateways on water, food insecurity, climate change, fragile states, maternal health, women and children, HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean, and Haiti, in addition to population.

Playing off a story that was already making world headlines, the Pulitzer Center supported reporting by freelance journalist Ellen Knickmeyer on the demographic dimensions of the Arab Spring, and particularly the role of young people. The stories explored youth’s frustration at high unemployment and lack of prospects, their roles in the revolutions, and their expectations for the future.

“Of course, we had the advantage that the world was interested in North Africa because of the amazing events that were taking place, but it was an opportunity to get them to look at the other dimension to it,” Sawyer said.

Based on a model developed to cover water and sanitation in West Africa, the Pulitzer Center also created a partnership with four African journalists to produce reporting on reproductive health that will be distributed in both international and African media outlets. “They have important things to say to American audiences, to international audiences,” Sawyer said. “And so we see this project as an opportunity to bring them into the international media discussion.” The journalists will be reporting from the upcoming International Conference on Family Planning in Dakar, Senegal, later this month.

Advocating Discussions

“It’s really a nuanced discussion, and that is why covering these topics, and looking at all the different aspects of it, is really important,” said USAID’s Heather D’Agnes. Furthermore, speaking as a development practitioner, she emphasized the importance of offering solutions, such as family planning, as part of an integrated development approach.

“In our journalism we don’t pretend not to have arguments, or ideas, or thoughts about the issues we are covering,” said Sheppard, speaking of Mother Jones. “I think that the value is that you tell the story well and you do solid reporting – that gives people a more informed perspective.” Especially with complicated issues, like population and the environment, “people find it more accessible if you have a perspective…they can associate better with a story if you walk them through the process you have gone through as a reporter.”

“What we are really trying to do is to advocate a discussion of issues that aren’t getting well-aired in other media,” said Dimick. Sometimes you need to find an interesting or counterintuitive framework, such as the National Geographic story about rural electrification and TV novelas in Brazil. It started as a story about the booming popularity of soap operas, but also created the opportunity to talk about gender equity, family planning, and other complex issues. While the magazine does not advocate a position, like the editorial page of a newspaper might, Dimick said, they do use case studies to guide readers through the range of risks, choices, and opportunities and to help them understand their implications.

Event ResourcesVideo Credit: “World’s Population Teeters on the Edge of 7 Billion — Now What?,” courtesy of PBS NewsHour; “7 Billion, National Geographic Magazine,” courtesy of National Geographic. -

Jotham Musinguzi on Investing in Family Planning for Development in Uganda

› “What we are seeing is not adequate, but we think we are seeing very good positive movement, and we want to build on that,” said Jotham Musinguzi, director of the African regional office for Partners in Population and Development (PPD) in Kampala, Uganda. Musinguzi is a public health physician by training who previously advised the government of Uganda on population and reproductive health issues. “We think that [the government] is now on a firm foundation to continue investing properly in family planning,” he said.

“What we are seeing is not adequate, but we think we are seeing very good positive movement, and we want to build on that,” said Jotham Musinguzi, director of the African regional office for Partners in Population and Development (PPD) in Kampala, Uganda. Musinguzi is a public health physician by training who previously advised the government of Uganda on population and reproductive health issues. “We think that [the government] is now on a firm foundation to continue investing properly in family planning,” he said.

Family Planning for Development

Uganda’s high population growth rate (the country has a total fertility rate of 6.4 children per woman, according to the UN) presents a number of challenges, said Musinguzi, exerting pressure on education and health systems, as well as on basic infrastructure, particularly for housing and transportation. Additionally, high levels of poverty and unemployment can become a source of instability.

Policymakers in Uganda are beginning to recognize the urgency of the issue, however, particularly in regards to young people, said Musinguzi. “They don’t have access to jobs, they don’t have the skills, and therefore the challenges of poverty eradication become even more important.”

Nonetheless, the country’s contraceptive prevalence rate is low, at 24 percent, with 41 percent of married women expressing an unmet need for family planning services, according to the 2006 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) for Uganda. Low levels of investment and lack of government involvement remain the primary obstacles, according to Musinguzi, in addition to socio-cultural and religious barriers.

Uganda historically depended primarily on donor finance, rather than government funding, to support family planning and reproductive health services, Musinguzi said. However, over the past two years, the Ugandan government has increased investment due to concerted efforts by PPD, as well as USAID, the UN Population Fund, and civil society groups. “Our point was that if the government does not fund family planning, then they are going to find that achievement of the Millennium Development Goals…is going to be very challenging,” he said.

“I think the low investment in family planning in Uganda is a thing of the past, and we are now looking forward to really better investment in this field,” Musinguzi said. “I am sure we are going to witness quite a big change [in the 2011 DHS] in terms of access as a result of the proper social investment that the government is trying to do now.”

South-South Collaboration

“I have a keen and strong interest in South-South collaboration in the field of reproductive health, family planning, population, and development,” Musinguzi said. Countries in the South have experience linking programming on population and development, and may face similar challenges, he said. For instance, Bangladesh and Vietnam had successful family planning programs that helped blunt rapid population growth rates.

“Countries, like Uganda, and others which haven’t gotten there yet, could learn from these other countries,” said Musinguzi, by sharing best practices and lesson learned, and replicating applicable solutions.

PPD also has a regional project reaching out to policymakers to increase commitment and accountability for family planning and reproductive health services. For instance, parliamentarians may not realize that they can play a significant role, but they have a unique function in providing government and budget oversight, Musinguzi said. Furthermore, they can create legal and administrative frameworks that prioritize family planning programs.

“We continue to make the case for more investment in family planning and reproductive health, but also making sure we hold leaders accountable, to show more commitment, and make sure they improve on the welfare of the people that they represent,” Musinguzi concluded.

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes.

Sources: MEASURE DHS, UN Population Division. -

Day of 7 Billion Puts Future Generations in Spotlight

›This month, our small planet’s population will hit seven billion. Reproductive health and environmental groups worldwide are raising awareness about the exact day – the “Day of Seven Billion” – when we’re estimated to hit that number next week, calling for sustainability and women’s empowerment. But the future trajectory of the world’s population projections – and all that they entail for human and environmental wellbeing – depends on decisions we make now.

Let’s start with the more than 215 million women worldwide – including many in our home countries, the United States and Kenya – who do not want to get pregnant but are not using modern contraception. Our world looks very different in 2050 if these women’s needs are met.

Research from the Futures Group shows that meeting women’s needs results in a significantly slowed population trajectory, with world population topping out at eight billion in 2050. According to recently revised UN estimates, without this intervention population could rise to 10 or even 12 billion by century’s end. Meeting this need is also a smart investment: Our research estimates that access to modern contraception for all who want it would cost $3.7 billion per year. Others have estimated the savings in health care costs of providing contraception to all who want it at $5.1 billion per year. Family planning is cost-effective; it has been estimated that a dollar spent on family planning can save between $15 and $20 in education, health, housing, and other socio-economic support costs, making the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals cheaper for developing countries.

The health and environmental benefits are also enormous: a one-third reduction in maternal mortality; a one-fifth reduction in child mortality; a major reduction in the greenhouse gas emissions. Recent research shows that carbon emissions slow when we slow our population trajectory in an effect similar to increasing the world’s use of wind power forty-fold. In Nigeria it was recently estimated that providing universal access to family planning would result in a reduction of carbon emissions equivalent to eight years from current sources.

These investments also provide more than big numbers: By enabling couples and women to choose when and how many children they’ll have, women can continue their educations longer, participate more in the workforce, and contribute to household decisions that benefit the family.

Giving women what they want and need to plan their pregnancies is one of the most obvious, yet most overlooked solutions to many of the most pressing problems we face, from maternal and child mortality to climate change. International family planning funding has stagnated for over 10 years and the results have been predictable: In Kenya, and in many countries, unmet need – with all its human costs – has increased.

Today, the largest generation of young people ever is coming of age. The aspirations and health of the millennial generation – as well as all those in the future – are on the line.

Pamela Onduso, MPH, is a Kenyan reproductive health advocate and program adviser with Pathfinder International’s Kenya office based in Nairobi. Dr. Scott Moreland is a senior researcher at the Futures Group, and leads demographic work in countries around the world.

Sources: African Institute for Development Policy, Futures Group, Guttmacher Institute, Health Policy Initiative, PNAS, Population Services International, UN Population Division, World Health Organization.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Tea picker and son,” courtesy of flickr user ROSS HONG KONG. -

Minority Youth Bulges and the Future of Intrastate Conflict

›October 13, 2011 // By Richard Cincotta

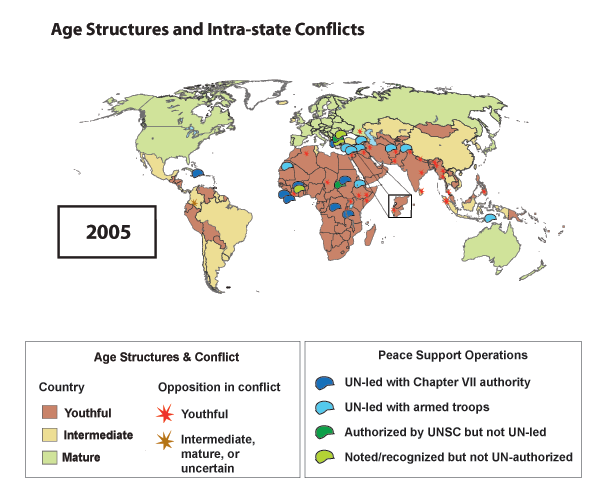

From a demographic perspective, the global distribution of intrastate conflicts is not what it used to be. During the latter half of the 20th century, the states with the most youthful populations (median age of 25.0 years or less) were consistently the most at risk of being engaged in civil or ethnoreligious conflict (circumstances where either ethnic or religious factors, or both, come into play). However, this tight relationship has loosened over the past decade, with the propensity of conflict rising significantly for countries with intermediate age structures (median age 25.1 to 35.0 years) and actually dipping for those with youthful age structures (see Figure 1 below).

-

Youth Bulge and Societal Conflicts: Have Peacekeepers Made a Difference?

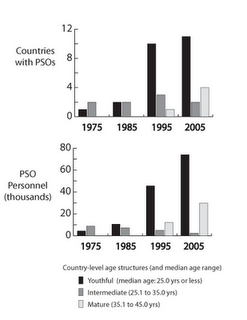

›August 22, 2011 // By Richard CincottaUntil recently, the question of which countries are at the most risk of violent societal conflict could be answered with a terse, two-part response: “the young and the war-torn.” This simple characterization regarding youth and conflict worked well, until the first decade of the 21st century. The proportion of youthful countries experiencing one or more violent intrastate conflicts declined from 25 percent in 1995 to 15 percent in 2005. What’s behind this encouraging slump in political unrest? One hypothesis is that peace support operations (PSOs) – peacekeepers, police units, and specialized observers that are led, authorized, or endorsed by the United Nations – have made a difference.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, more than 90 percent of all societal conflicts broke out in countries with a youthful age structure – a population with a median age of 25 years or less. And wherever civil and ethnic wars emerged, they tended to persist. The average societal conflict that began between 1970 and 1999 continued without a one-year break in battle-associated fatalities for about six years. Some – including the Angolan civil war, Northern Ireland’s “Troubles,” Peru’s war against the Shining Path, and the Afghan civil war – endured for decades. In contrast, inter-state conflicts that began between 1970 and 1999 lasted, on average, less than two years (see the UCDP/PRIO Conflict Database).

Taking on Intra-State Conflicts Beginning in the early 1990s, however, there was a marked expansion in size and number of PSOs deployed in the aftermath of societal warfare, which appears to have dampened the persistence of some conflicts and prevented the reemergence of others. The annual number of active PSOs deterring the re-emergence of societal conflict jumped from just 2 missions during 1985 to 22 in 2005. In contrast, those led, authorized, or endorsed by the UN to maintain cease-fire agreements between neighboring states during that same period only increased from three active missions to four. By 2009, nearly 100,000 peacekeepers were stationed in countries that had recently experienced a societal conflict. About 70 percent were deployed in countries with a youthful population (see Figures 2A and B). Why the sudden expansion in use of PSOs?

Beginning in the early 1990s, however, there was a marked expansion in size and number of PSOs deployed in the aftermath of societal warfare, which appears to have dampened the persistence of some conflicts and prevented the reemergence of others. The annual number of active PSOs deterring the re-emergence of societal conflict jumped from just 2 missions during 1985 to 22 in 2005. In contrast, those led, authorized, or endorsed by the UN to maintain cease-fire agreements between neighboring states during that same period only increased from three active missions to four. By 2009, nearly 100,000 peacekeepers were stationed in countries that had recently experienced a societal conflict. About 70 percent were deployed in countries with a youthful population (see Figures 2A and B). Why the sudden expansion in use of PSOs?

According to William Durch and Tobias Berkman, this upsurge was less a change of heart or modification of a global security strategy and more an outcome of the unraveling web of Cold War international relations. Before the 1990s, the majority of PSOs were United Nations-led operations that were mandated to monitor or help maintain cease-fires along mutual frontiers. Because insurgents were typically aligned with either the Soviets or a Western power, Security Council authorization to mediate a societal conflict was difficult to secure.

This situation changed with the breakup of the Soviet Union and the initiation of PSOs by regional organizations, including operations by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in Liberia and Sierra Leone and the NATO-led Kosovo Force in 1998-99.

Demographic Forecasting

What do national demographic trends suggest for the demand for PSOs over the next two decades? For societal conflict, political demographers foresee that the demand for PSOs will continue to decline among states in Latin America and the Caribbean – with the exception of sustained risk in Guatemala, Haiti, Bolivia, and Paraguay. Similarly, demand for peacekeeping is expected to continue to ebb across continental East Asia.

Gauged by age structure alone, the risk of societal warfare is projected to remain high over the coming two decades in the western, central, and eastern portions of sub-Saharan Africa; in parts of the Middle East and South Asia; and in several Asian-Pacific island hotspots – Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and Solomon Islands. But even in some countries that are losing their youthful blush, domestic political relations could turn out less rosy than this simple age-structural model forecasts.

In other words, there are roadblocks to a “demographic peace.” Among them is an increasing propensity for a specific demographic configuration of ethnic conflict: warfare between state forces and organizations that recruit from a minority that is more youthful than the majority ethnic group. Examples of these conflicts include the Kurds in Turkey, the Shiites in Lebanon, the Pattani Muslims in southern Thailand, and the Chechens of southern Russia.

However, this twist on the youth bulge model of the risks of societal conflict is a discussion for another installment on New Security Beat. Suffice it to say that when political demographers look over the UN Population Division’s current demographic projections, they see few signs of either the waning of societal warfare, or the withering of the current level of demand for PSOs.

Richard Cincotta is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and demographer-in-residence at The Stimson Center.

Sources: PRIO, The Stimson Center, UN Population Division.

Chart Credit: Data courtesy of the UN Population Division 2011, PRIO, and Durch and Berkman (2006). Arranged by Richard Cincotta. -

PRB’s Population Data Sheet 2011: The Demographic Divide

›August 9, 2011 // By Kellie Furr“Today, most population growth is concentrated in the world’s poorest countries – and within the poorest regions of those countries,” write the authors of the 2011 Population Data Sheet, an analysis tool published annually by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB). The population projections between poor and rich countries are “stark and very sad,” said Carl Haub Haub, senior demographer at PRB, at the July 28 web-based launch of the Data Sheet: “We call it the demographic divide. It shows the vast difference that has developed between the rich and poor countries of the world.”

The Population Data Sheet offers insight on global population trends using detailed statistical information along 18 demographic, population, health, and environment indicators for more than 200 countries and regions. The data sheet is based on the latest projections of the UN Population Division. Carl Haub and James Gribble of PRB discussed the long-term implications of the data sheet’s projections during web-based launch that included open questions.

Conflicting Trends

“Even though the world population growth rate has slowed from 2.1 percent per year in the late 1960s to 1.2 percent today, the size of the world’s population has continued to increase – from 5 billion in 1987, to 6 billion in 1999, and to 7 billion in 2011,” write the authors in PRB’s July Population Bulletin, “The World at 7 Billion.” To put those population totals into perspective, it took from the inception of human existence until the year 1800 – a total of approximately 50,000 years – to reach the first billion.

Fortunately, the recent (relative) decline in global growth rate has already curbed what could have been a considerable surge in the world’s population: “If the late 1960s population growth rate of 2.1 percent – the highest in history – had held steady, world population would have grown by 117 million annually, and today’s population would have been 8.6 billion,” said PRB President Wendy Baldwin in a press release. However, the world’s population still grows significantly at 77 million people annually, according to the UN, and we’re slated to reach 8 billion in just another 12 years. How can this dichotomy of large population totals in the face of lowered fertility be explained?

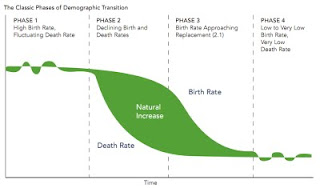

The Phases of Demographic Transition

“To understand global, we actually have to think local,” said PRB in their film short, “7 Billion and Counting,” released alongside the data sheet. Individual countries go through demographic transitions at different times, and the disparity in where countries are along in their progression varies greatly.

A demographic transition essentially hinges on two trends: the decline of birth and death rates over time. These trends do not necessarily change simultaneously however, resulting in most cases, first, a natural increase (when mortality rates decline but birth rates remain high) followed by a natural decrease in population (when birth rates also decline). Though the timing and magnitude of these trends differ from place to place, there are broad similarities across countries which have been conceptualized as phases by demographers, such as Carl Haub and James Gribble.

Phase one is characterized by high birth rates and fluctuating death rates, found in countries such as Niger, Afghanistan, and Uganda; typically only death rates decline in this phase. Phase two, encompassing mostly lower-middle income countries such as Guatemala, Ghana, and Iraq, is marked by a continued decline in death rates but only slightly lower birth rates. The potential for large population growth exists in these countries, as they still possess a large youth population.

Countries in phase three have yet lower birth and death rates and overall total fertility rates close to the widely-accepted replacement level of 2.1 children per woman; these countries are home to approximately 38 percent of the world’s population and include India, Malaysia, and South Africa. Phase three countries often still possess a disproportionately large working age population as an echo of their previous growth, which allows them to take advantage of the “demographic dividend.”

Finally, phase four countries have the lowest birth and death rates, with some even seeing negative growth as total fertility rate falls at or below the natural replacement rate; countries in this phase include most of Europe and other developed countries, such as Japan and the United States (though relatively high levels of immigration keeps overall growth higher).

The data sheet shows that most developing countries still remain in the earlier phases of demographic transition, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Relatively recent public health improvements in these countries have decreased death rates at a rapid rate, and though total fertility rates (TFR) have declined as well, they have not kept the same pace: “This lag between the drop in death rates and the drop in birth rates produced unprecedented levels of population growth,” wrote Haub and Gribble in the Population Bulletin.

A Tale of Two Worlds

The data sheet authors observe that poverty is strongly associated with countries which are stalled in their progression through the demographic transition:Poverty has emerged as a serious global issue, particularly because the most rapid population growth is occurring in the world’s poorest countries and, within many countries, in the poorest states and provinces…Relatively high population growth rates make it more difficult to lift large numbers of people out of poverty.

In her primer video on demographic security for ECSP, demographer Elizabeth Leahy Madsen said, “we are in an era of unprecedented demographic divergence,” and characterized the phenomenon of population trends moving simultaneously in different directions as “rapid” and “unprecedented.”

Haub used Italy and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as an example to illustrate the divide. Although both countries currently sit at around 60 million people each, Italy is only projected to grow by 2 million through 2050, while the DRC is projected to reach a staggering 149 million people. Italy has a gross national income per capita of about $35,000, whereas DRC has only $180 per capita, according to the World Bank.

This observation has been corroborated by other demographers: “In 1950, 68 percent of the world’s population resided in developing regions. Today that’s up to 82 percent. But in the year 2050, it’s projected to be 86 percent,” said demographer David Bloom on NPR’s global health blog, Shots.

Demography ≠ Destiny

A poor country is not necessarily tethered to its projections, which are based on assumptions, said the authors, “but when, how, and whether [the demographic transition] actually happens cannot be known.”

Low development indicators do not always dictate that a country will lag in a demographic transition. “Government commitment to a policy to lower [birth rates] has succeeded quite well in countries with a low level of development,” said Haub in a 2008 PRB discussion on the demographic divide. Bangladesh and Iran are two examples of countries that significantly affected their demographic trajectories in the 20th century with targeted programs.

Proactivity certainly plays a role, as the PRB “7 Billion and Counting” video puts it (see above): “Understanding how and why the world’s population is growing will help nations better plan for the future…and for future generations.”

Sources: NPR, Population Reference Bureau, UN-DESA, UNICEF, World Bank.

Video and Image Credit: “7 Billion and Counting,” courtesy of PRB’s Youtube channel, and stages of demographic transition courtesy of PRB’s 2011 Population Data Sheet.

Showing posts from category youth.