Showing posts from category water.

-

Redrawing the Map of the World’s International River Basins

›Understanding why conflict over water resources arises between nations begins with a solid understanding of the geography of international river basins. Where are the basins? How big are they? How many people live there? Who are the riparian nations, and what is the significance of each to the basin?

-

Russell Sticklor, World Politics Review

The Hungry Planet: Global Food Scarcity in the 21st Century

›August 16, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Russell Sticklor, appeared on World Politics Review.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the world population was inching toward a modest two billion. In the 111 years since, notwithstanding the impact of war, genocide, disease, and famine, the global population has soared, reaching three billion around 1960 and now quickly approaching the neighborhood of seven billion. By 2050, the planet will likely be home to two billion more.

We may not be witnessing the detonation of the “population bomb” that Paul Ehrlich warned of in his seminal 1968 book, but such rapid demographic change is clearly pushing the international community into uncharted territory. With a limited amount of arable land and a finite supply of fresh water for irrigation, figuring out how to feed a planet adding upward of 70 million people each year looms as one of the 21st century’s most pressing challenges.

The push to ensure global food security transcends the desire to avoid repeating the famines that devastated the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, Ethiopia, and so many other corners of the world during the past century. Instead, aid and development organizations today rightly view food insecurity problems as deeply intertwined with issues of economic development, public health, and political stability, particularly in the developing world. To maintain order in the international community and prevent the emergence of new failed states in the decades ahead, it will be critical to find innovative means of feeding the rapidly growing populations of sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and South and East Asia.

Continue reading on World Politics Review.

Note: World Politics Review has graciously white-listed all entrances from NSB for this article, so as long as you use the above link, you should be able to read the full article for free.

Russell Sticklor is a consultant for the Environmental Change and Security Program.

Photo Credit: “Crowded market street,” courtesy of flickr user – yt –. -

International River Basins: Mapping Institutional Resilience to Climate Change

›Institutions that manage river basins must assess their ability to deal with variable water supplies now, said Professor Aaron Wolf of Oregon State University at the July 28 ECSP event, “International River Basins: Mapping Institutional Resilience to Change.” “A lot of the world currently can’t deal with the variability that they have today, and we see climate change as an exacerbation to an already bad situation.”

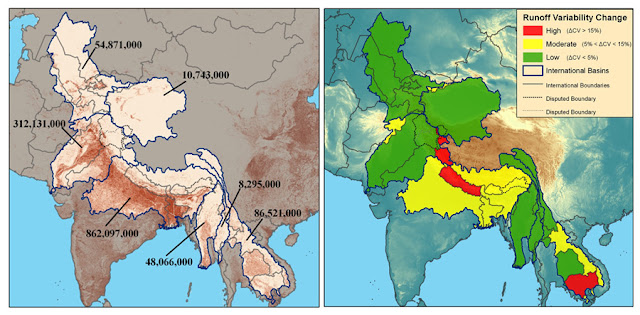

Wolf and his colleagues, Jim Duncan of the World Bank and Matt Zentner of the U.S. Department of Defense, discussed their efforts to map basins at risk for future tensions over water, as identified in their coauthored World Bank report, “Mapping the Resilience of International River Basins to Future Climate Change-Induced Water Variability.” [Video Below]

Floating Past the Rhetoric of “Water Wars”

Currently, there are 276 transnational water basins that cross the boundaries of two or more countries, said Wolf. “Forty percent of the world’s population lives within these waters, and interestingly, 80 percent of the world’s fresh water originates in basins that go through more than one country,” he said. Some of these boundaries are not particularly friendly – those along the Jordan and Indus Rivers, for example – but “to manage the water efficiently, we need to do it cooperatively,” he said.

Wolf and his colleagues found that most of the rhetoric about “water wars” was merely anecdotal, so they systematically documented how countries sharing river basins actually interact in their Basins at Risk project. The findings were surprising and counterintuitive: “Regularly we see that at any scale, two-thirds of the time we do anything over water, it is cooperative,” and actual violent conflict is extremely rare, said Wolf.

Additionally, the regions where they expected to see the most conflict – such as arid areas – were surprisingly the most cooperative. “Aridity leads to institutions to help manage aridity,” Wolf said. “You don’t need cooperation in a humid climate.”

“It’s not just about change in a basin, it’s about the relationship between change and the institutions that are developed to mitigate the impacts of change,” said Wolf. “The likelihood of conflict goes up when the rate of change in a basin exceeds the institutional capacity to absorb the change.”

Expanding the Database for Risk Assessment

Oregon State University’s Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) tracks tabular and spatial information on more than 680 freshwater treaties along 276 transboundary river basins, said Jim Duncan. The team expanded the database to include recent findings on variability, as well as the impacts of climate change on the future variability of those basins. “We have a lot more information that we are able to work with now,” Duncan said.

Analyzing the institutional vulnerability of treaties along with hydrological hazards, they found the risk of tension concentrated in African basins: The Niger, Congo, and Lake Chad basins “popped out,” said Duncan. When predicting future challenges, they found that basins in other areas, such as Southeastern Asia and Central Europe, would also be at risk.

Duncan and his colleagues were able to identify very nuanced deficiencies in institutional resilience. “Over half of the treaties that have ever been signed deal with variability only in terms of flood control, and we’re only seeing about 15 percent that deal with dry season control,” said Duncan. “It’s not the actual variability, but the magnitude of departure from what they’re experiencing now that is going to be really critical.”

Beyond Scarcity

“Generally speaking, it’s not really the water so much that people are willing to fight over, but it’s the issues associated with water that cause people to have disagreements,” said Matt Zentner. Water issues are not high on the national security agendas of most governments; they only link water to national security when it actively affects other sectors of society, such as economic growth, food availability, and electric power, he said. Agricultural production – the world’s largest consumer of water – will be a major concern for governments in the future, he said, especially in developing countries economically dependent on farming.

Some experts think that current international treaties are not enough, said Zentner. Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute has said that “the existing agreements and international principles for sharing water will not adequately handle the strain of future pressures, particularly those caused by climate change.”

How transboundary water treaties fare as the climate and consumption rates change is not as simple as measuring flow; the strength of governing institutions, the parties involved, and other variables all play major roles as well, said Zentner. “When you have flexibility built within [a treaty], it allows it to be a living, breathing, and important part of solving those [water] problems.”

Download the full event transcript here.

Sources: Oregon State University, Pacific Institute.

Photo Credit: “Confluence of the Zanskar and Indus,” courtesy of Flickr user Sanish Suresh. -

Watch: Aaron Wolf on the Himalayan and Other Transboundary Water Basins, Climate Change, and Institutional Resilience

›When Aaron Wolf, professor in the Department of Geoscience at Oregon State University, and his colleagues first looked at the dynamics behind water conflict in their Basins at Risk study, they found that a lot of the issues they’d assumed would lead to conflict, like scarcity or economic growth, didn’t necessarily. Instead they found that “there is a relationship between change in a [water] basin and the institutional capacity to absorb that change,” said Wolf in this interview with ECSP. “The change can be hydrologic: you’ve got floods, droughts, agricultural production growing…or institutions also change: countries kind of disintegrate, or there are new nations along basins.”

However, these changes happen independently. “Whether there is going to be conflict or not depends in a large part to what kind of institutions there are to help mitigate for the impacts of that change,” explained Wolf.

“If you have a drought or economic boom within a basin and you have two friendly countries with a long history of treaties and working together, the likelihood of that spiraling into conflict is fairly low. On the other hand, the same droughts or same economic growth between two countries that don’t have treaties, or there is hostility or concern about the motives of the other, that then could lead to settings that are more conflictive.”

Wolf stressed the importance of understanding hydrologic variability in relation to existing treaties around the world. After carefully examining hundreds of treaties, he and his colleagues created a way of measuring their variability to try to find potential hotspots.

“We know how variable basins are around the world; we know how well treaties can deal with variability. You put them together and you have some areas of concern: You may want to look a little closely to see what is happening as people try to mitigate these impacts,” said Wolf.

“We know that one of the overwhelming impacts of climate change is that the world is going to get more variable: Highs are going to be higher, and lows are going to be lower,” Wolf said.

Wolf used the Himalayan basins to illustrate the importance of overseeing the potential effects of climate change and institutional capacity. “There are a billion and half people who rely on the waters that originate in the Himalayas,” he pointed out. Because of climate change, the Himalayas may experience tremendous flooding, and conversely, extreme drought.

Unfortunately, Wolf said, “the Himalayan basins…do not have any treaty coverage to deal with that variability.” Without treaties, it is difficult for countries to cooperate and setup a framework for mitigating the variability that might arise. -

Lakis Polycarpou, Columbia Earth Institute

The Year of Drought and Flood

›August 1, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Lakis Polycarpou, appeared on the Columbia Earth Institute’s State of the Planet blog.

On the horn of Africa, ten million people are now at risk as the region suffers the worst drought in half a century. In China, the Yangtze – the world’s third largest river – is drying up, parching farmers and threatening 40 percent of the nation’s hydropower capacity. In the U.S. drought now spreads across 14 states creating conditions that could rival the dust bowl; in Texas, the cows are so thirsty now that when they finally get water, they drink themselves to death.

And yet this apocalyptic dryness comes even as torrential springtime flooding across much of the United States flows into summer; even as half a million people are evacuated as water rises in the same drought-ridden parts of China.

It seems that this year the world is experiencing a crisis of both too little water and too much. And while these crises often occur simultaneously in different regions, they also happen in the same places as short, fierce bursts of rain punctuate long dry spells.

The Climate Connection

Most climate scientists agree that one of the likely effects of climate will be an acceleration of the global water cycle, resulting in faster evaporation and more precipitation overall. Last year, the Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences published a study which suggested that such changes may already be underway: According to the paper, annual fresh water flowing from rivers into oceans had increased by 18 percent from 1994 to 2006. It’s not hard to see how increases in precipitation could lead to greater flood risk.

At the same time, many studies make the case that much of the world will be dramatically drier in a climate-altered future, including the Mediterranean basin, much of Southwest and Southeast Asia, Latin America, the western two-thirds of the United States among other places.

Continue reading on State of the Planet.

Sources: Associated Press, The New York Times, Proceedings from the National Academy of Sciences, Reuters, Science Magazine, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.

Photo Credit: “Drought in SW China,” courtesy of flickr user Bert van Dijk. -

Edward Carr, Open the Echo Chamber

Drought Does Not Equal Famine

›July 27, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Edward Carr, appeared on Open the Echo Chamber.

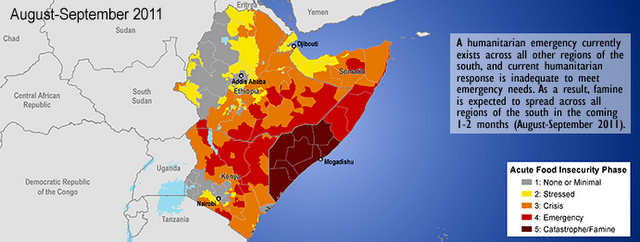

After reading a lot of news and blog posts on the situation in the Horn of Africa, I feel the need to make something clear: The drought in the Horn of Africa is not the cause of the famine we are seeing take shape in southern Somalia. We are being pounded by a narrative of this famine that more or less points to the failure of seasonal rains as its cause…which I see as a horrible abdication of responsibility for the human causes of this tragedy.

First, I recommend that anyone interested in this situation – or indeed in food security and famine more generally, to read Mike Davis’ book Late Victorian Holocausts. It is a very readable account of massive famines in the Victorian era that lays out the necessary intersection of weather, markets, and politics to create tragedy – and also makes clear the point that rainfall alone is poorly correlated to famine. For those who want a deeper dive, have a look at the lit review (pages 15-18) of my article “Postmodern Conceptualizations, Modernist Applications: Rethinking the Role of Society in Food Security” to get a sense of where we are in contemporary thinking on food security. The long and short of it is that food insecurity is rarely about absolute supplies of food – mostly it is about access and entitlements to existing food supplies. The Horn of Africa situation does actually invoke outright scarcity, but that scarcity can be traced not just to weather – it is also about access to local and regional markets (weak at best) and politics/the state (Somalia lacks a sovereign state, and the patchy, ad hoc governance provided by Al Shabaab does little to ensure either access or entitlement to food and livelihoods for the population).

For those who doubt this, look at the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) maps I put in previous posts here and here (Editor: also above). Famine stops at the Somali border. I assure you this is not a political manipulation of the data – it is the data we have. Basically, the people without a functional state and collapsing markets are being hit much harder than their counterparts in Ethiopia and Kenya, even though everyone is affected by the same bad rains, and the livelihoods of those in Somalia are not all that different than those across the borders in Ethiopia and Kenya. Rainfall is not the controlling variable for this differential outcome, because rainfall is not really variable across these borders where Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia meet.

Continue reading on Open the Echo Chamber.

Image Credit: FEWS NET and Edward Carr. -

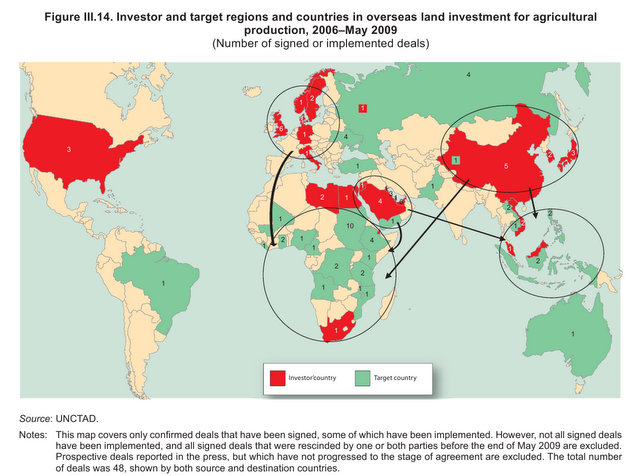

In Rush for Land, Is it All About Water?

›July 26, 2011 // By Christina DaggettOver the past few years, wealthy countries with shrinking stores of natural resources and relatively large populations (such as China, India, South Korea, and the Gulf states) have quietly purchased huge parcels of fertile farmland in Africa, South America, and South Asia to grow food for export to the parent country. With staple food prices shooting up and food security projected to worsen in the decades ahead, it is little wonder that countries are looking abroad to secure future resources. But the question arises: Are these “land grabs” really about the food — or, more accurately, are they “water grabs”?

The Great Water Grab

With growing urban populations, an expanding middle class, and increasingly scarce arable land resources, some governments and investors are snapping up the world’s farmland. Some observers, however, have pointed out that these dealmakers might be more interested in the water than the land.

In an article from The Economist in 2009, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, the chairman of Nestlé, claimed that “the purchases weren’t about land, but water. For with the land comes the right to withdraw the water linked to it, in most countries essentially a freebie that increasingly could be the most valuable part of the deal.”

Consider some of the largest investors in foreign land: China has a history of severe droughts (and recently, increasingly poor water quality); the Gulf nations of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain are among the world’s most water-stressed countries; and India’s groundwater stocks are rapidly depleting.

A recent report from the World Bank on global land deals highlighted the effect water scarcity is having on food production in China, South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, stating that “in contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America have large untapped water resources for agriculture.”

Keeping Engaged and Informed

“The water impacts of any investment in any land deal should be made explicit,” said Phil Woodhouse of the University of Manchester during the recent International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, as reported by the New Agriculturist. “Some kind of mechanism is needed to bring existing water users into an engagement on any deals done on water use.”

At the same conference, Shalmali Guttal of Focus on the Global South cautioned, “Those who are taking the land will also take the water resources, the forests, wetlands, all the wild indigenous plants and biodiversity. Many communities want investments but none of them sign up for losing their ecosystems.”

With demand for water expected to outstrip supply by 40 percent within the next 20 years, water as the primary motivation behind the rush for foreign farmland is a factor worth further exploration.

Global Farming

According to a report from the Oakland Institute, nearly 60 million hectares (ha) of African farmland – roughly the size of France – were purchased or leased in 2009. With these massive land deals come promises of jobs, technology, infrastructure, and increased tax revenue.

In 2008 South Korean industrial giant Daewoo Logistics negotiated one of the biggest African farmland deals with a 99-year lease on 1.3 million ha of farmland in Madagascar for palm oil and corn production. The deal amounted to nearly half of Madagascar’s arable land – an especially staggering figure given that nearly a third of Madagascar’s GDP comes from agriculture and more than 70 percent of its population lives below the poverty line. When details of the deal came to light, massive protests ensued and it was eventually scrapped after president Marc Ravalomanana was ousted from power in a 2009 coup.

While perhaps an extreme example, the Daewoo/Madagascar deal nonetheless demonstrates the conflict potential of these massive land deals, which are taking place in some of the poorest and hungriest countries in the world. In 2009, while Saudi Arabia was receiving its first shipment of rice grown on farmland it owned in Ethiopia, the World Food Program provided food aid to five million Ethiopians.

Other notable deals include China’s recent acquisition of 320,000 ha in Argentina for soybean and corn cultivation – a project which is expected to bring in $20 million in irrigation infrastructure, the Guardian reports – and a Saudi Arabian company which has plans to invest $2.5 billion and employ 10,000 people in Ethiopia by 2020, according to Gambella Star News.

But governments in search of cheap food aren’t the only ones interested in obtaining a piece of the world’s breadbasket: Individual investors are also heavily involved, and the Guardian reports that U.S. universities and European pension funds are buying and leasing land in Africa as well.

The Future of Land and Water

Whatever the benefits or pitfalls, large-scale land deals around the world look set to continue. The world is projected to have 7 billion mouths to feed by the end of this year and possibly 10 billion plus by the end of the century.

Currently, agriculture uses 11 percent of the world’s land surface and 70 percent of the world’s freshwater resources, according to UNESCO. If and when the going gets tough, how will the global agricultural system respond? Whose needs come first – the host countries’ or the investing nations’?

Christina Daggett is a program associate with the Population Institute and a former ECSP intern.

Photo Credit: Number of signed or implemented overseas land investment deals for agricultural production 2006-May 2009, courtesy of GRAIN and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Sources: BBC News, Canadian Water Network, Christian Science Monitor, Circle of Blue, The Economist, Gambella Star News, Guardian, Maplecroft, New Agriculturalist, Oakland Institute, State Department, Time, UNFPA, UNESCO, World Bank, World Food Program. -

Water, Energy, and the U.S. Department of Defense

› Energy for the War Fighter is the U.S. Department of Defense’s first operational energy strategy, mandated by congress last year. Energy security for the department means having assured access to reliable supplies of energy and the ability to protect and deliver energy to meet operational (non-facilities-related) needs. The report is divided into three main parts, which address reducing current demand for energy in military operations; expanding and securing the supply of energy for military operations; and building consideration of energy security into future force decisions. The strategy is designed to both support current military operations and to focus future energy investments accordingly. Previous federal energy mandates exempted the military’s field operations, which account for three-quarters of the department’s energy consumption. The department as a whole makes up 80 percent of the federal government’s annual energy use.

Energy for the War Fighter is the U.S. Department of Defense’s first operational energy strategy, mandated by congress last year. Energy security for the department means having assured access to reliable supplies of energy and the ability to protect and deliver energy to meet operational (non-facilities-related) needs. The report is divided into three main parts, which address reducing current demand for energy in military operations; expanding and securing the supply of energy for military operations; and building consideration of energy security into future force decisions. The strategy is designed to both support current military operations and to focus future energy investments accordingly. Previous federal energy mandates exempted the military’s field operations, which account for three-quarters of the department’s energy consumption. The department as a whole makes up 80 percent of the federal government’s annual energy use. The Water Energy Nexus: Adding Water to the Energy Agenda, by Diana Glassman, Michele Wucker, Tanushree Isaacman, and Corinne Champilouis of the World Policy Institute, attempts to show the correlation between energy and water to motivate policy makers to consider the implications of their dual consumption. “Nations around the world are evaluating their energy options and developing policies that apply appropriate financial carrots and sticks to various technologies to encourage sustainable energy production, including cost, carbon, and security considerations,” write the authors. “Water needs to be a part of this debate, particularly how communities will manage the trade-offs between water and energy at the local, national, and cross-border levels.” The study provides the context needed to evaluate key tradeoffs between water and energy by providing “the most credible available data about water consumption per unit of energy produced across a wide spectrum of traditional energy technologies,” they write.

The Water Energy Nexus: Adding Water to the Energy Agenda, by Diana Glassman, Michele Wucker, Tanushree Isaacman, and Corinne Champilouis of the World Policy Institute, attempts to show the correlation between energy and water to motivate policy makers to consider the implications of their dual consumption. “Nations around the world are evaluating their energy options and developing policies that apply appropriate financial carrots and sticks to various technologies to encourage sustainable energy production, including cost, carbon, and security considerations,” write the authors. “Water needs to be a part of this debate, particularly how communities will manage the trade-offs between water and energy at the local, national, and cross-border levels.” The study provides the context needed to evaluate key tradeoffs between water and energy by providing “the most credible available data about water consumption per unit of energy produced across a wide spectrum of traditional energy technologies,” they write.

Sources: U.S. Department of Defense.