-

Integration, Communication Across Sectors a Must, Say Speakers at 2012 NCSE Environment and Security Conference (Updated)

›February 23, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffECSP staff were among the more than 1,000 attendees discussing non-traditional security issues at the 12th National Conference on Science, Policy, and the Environment last month at the Ronald Reagan Building. Our own Geoff Dabelko spoke on the opening plenary (above) and we collected other excerpts below, though they’re only a small slice of the conference. Find our full coverage by following the NCSE tag, see the full agenda on environmentalsecurity.org, and follow the conversation on Twitter (#NCSEconf).

Climate, Energy, Food, Water, and Health

At the conference’s lead-off plenary, Jeff Seabright (Vice President, The Coca-Cola Company), Daniel Gerstein (Deputy Under Secretary for Science and Technology, U.S. Department of Homeland Security), Rosamond Naylor (Director, Stanford’s Center on Food Security and Environment), and our ECSP’s Geoff Dabelko highlighted the challenges and opportunities of addressing the diverse yet interconnected issues of climate, energy, food, water, and health.

“We need to embrace diversity regardless of the complexity,” said Dabelko, and “abandon our stereotypes and get out of our stovepipes.” Government agencies, academics, and NGOs must be open to using different tools and work together to capture synergies. “If we know everyone in the room, we are not getting out enough,” he said.

“We have to be concerned with every level – national, state, tribal, regional, down to the individual,” said Gerstein. DHS recognizes that climate change affects all of its efforts, and has established three main areas of focus: Arctic impacts; severe weather; and critical infrastructure and key resources.

For Coca-Cola, “managing the complex relationship among [food, water, and energy] is going to be the challenge of the 21st century, said Seabright, who noted that the business community is “seeing a steady increase in the internalization of these issues into business,” including as part of companies’ competitive advantages and strategies.

Similarly, we must offer opportunities and not just threats, said Dabelko, such as exploring climate adaptation’s potential as a tool for peacebuilding rather than simply focusing on climate’s links to conflict. We need to “find ways to define and measure success that embrace the connections among climate, water, and energy, and does not try to pretend they aren’t connected in the real world,” he said.

Communicating Across Sectors: Difficult But Necessary

Next, Sherri Goodman (Executive Director, CNA Military Advisory Board), Nancy Sutley (Chair, White House Council on Environmental Quality), Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti (Climate and Energy Security Envoy, UK Ministry of Defence), and Susan Avery (Director, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute) called on governments, militaries, and institutions to move away from traditional, vertically segmented responsibilities to address today’s environmental and security challenges.

“We live in an interdependent, connected world,” Morisetti said, but communicating that is a challenge. Militaries are likely to have new, broader missions, including conflict prevention, he said, which makes communications all the more important.

Science is moving from reductive to integrated outlooks to better address larger, systems-wide challenges, said Avery, but communicating results of this research to the public, and across and between disciplines, is difficult.

Confronting these communication and education challenges, particularly the difficulties of conveying the probability of various risks, is a key focus of the Council on Environmental Quality, said Sutley. “We confront the challenge of risk communication every day and it’s not limited to climate change,” she said.Challenging Conventional Wisdom on Climate and Conflict

The common argument is that climate change will lead to scarcity – less arable land, water, rain, etc. – and scarcity will lead to conflict, said Kate Marvel (Lawrence Livermore National Lab). But the link between scarcity and conflict is not that clear. It’s “very important to treat models as tools, not as magic balls,” she said. Developing better diagnostics to test models will help researchers and observers sort out which ones are best.

Kaitlin Shilling (Stanford University) called on the environmental security community to move beyond simple causal pathways towards finding solutions. After all, rolling back climate change is not an option at this point, she said; to find solutions, therefore, we need more detailed analysis of the pathways to violence.

The most common types of climate-conflict correlations are not likely to directly involve the state, said Cullen Hendrix (College of William and Mary). Traditional inter-state wars (think “water wars”) or even civil wars are much less likely than threats to human security (e.g., post-elections violence in Kenya) and community security (e.g., tribal raiding in South Sudan). For this reason, the biggest breakthroughs in understanding climate and conflict links will likely come from better interactions between social and physical scientists, he said.

Because the many unique factors leading to conflict vary from place to place, a better way to assess climate-conflict risk might be mapping human vulnerability to climate change rather than predicting conflict risk in a given place, said Justin Mankin (Stanford University). While human reactions are very difficult to predict, vulnerability is easier to quantify.

Yu Hongyuan (Shanghai Institute for International Studies) compared the concerns of U.S. and Chinese officials on climate change. Polling results, he said, show Chinese officials are most concerned with maintaining access to resources, while American policymakers focus on climate change’s effects on global governance and how it will impact responses to natural disasters, new conflicts, and humanitarian crises. Given the centrality of these two countries to international climate negotiations, Yu said he hoped the “same issues, different values” gulf might be bridged by better understanding each side’s priorities.

Schuyler Null, Lauren Herzer, and Meaghan Parker contributed to this article.

Video Credit: Lyle Birkey/NCSE; photo credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center. -

Kaitlin Shilling: Climate Conflict and Export Crops in Sub-Saharan Africa

› “There’s been a tremendous amount of work done on looking for a climate signal for civil conflict, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and a lot of this work draws a very clear and simple path – if it rains more, or if it rains less, there will be more or less conflict,” says Stanford University’s Kaitlin Shilling in this short video interview. Unfortunately, that straightforward research does little in the way of helping policymakers: “the only way to change the agricultural outputs due to climate change is to change climate change, reduce climate change, or stop it,” she says, “and we’re not really good at that part.”

“There’s been a tremendous amount of work done on looking for a climate signal for civil conflict, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and a lot of this work draws a very clear and simple path – if it rains more, or if it rains less, there will be more or less conflict,” says Stanford University’s Kaitlin Shilling in this short video interview. Unfortunately, that straightforward research does little in the way of helping policymakers: “the only way to change the agricultural outputs due to climate change is to change climate change, reduce climate change, or stop it,” she says, “and we’re not really good at that part.”

Shilling moderated a panel at last month’s National Conference on Science, Policy, and the Environment on climate-conflict research. Agricultural export crops – cotton, coffee, cocoa, tea, vanilla – represent one area where policymakers might be able to intervene to prevent climate-driven conflict, says Shilling. Though not as important from a food security perspective, “these crops are really important” for sub-Saharan economies, as well as for “government revenues, which [are] closely related to government capacity.”

But “the effects of climate change on those crops are less well understood,” Shilling says. How they relate to “government revenues and how those relate to civil conflict is an area that I spend a lot of time doing research on.”

By “understand[ing] the mechanisms that underlie the potential relationship between climate and conflict, we can start identifying interventions that make sense to reduce the vulnerability of people to conflict and help them to adapt to the coming climate change.” -

Stuck: Rwandan Youth and the Struggle for Adulthood (Book Preview)

›

Several years ago, I wrote that the central irony concerning Africa’s urban youth was that “they are a demographic majority that sees itself as an outcast minority.” Since that time, field research with rural and urban youth in war and postwar contexts within and beyond Africa has led me to revise this assertion. The irony appears to apply to most developing country youth regardless of their location.

-

The Ramsar Convention: A New Window for Environmental Diplomacy?

›In seeking ways to connect conservation with peacemaking, the Institute for Environmental Diplomacy and Security (IEDS) has released a study that examines an expanded role for the international wetlands treaty, the Ramsar Convention.

The Ramsar Convention: A New Window for Environmental Diplomacy? describes the wetlands convention, its place within the international environmental treaty world, and its potential to enhance environmental security during this dynamic time of increasingly insecure water supplies and climate change. With more than 40 years of work, the treaty has been quietly and effectively conserving wetlands and increasing recognition of the need to build international cooperation around them. The treaty has also helped define wetlands within greater biogeographic regions and led to formal identification of transboundary wetlands.

In the article, we set out to combine information from the convention’s 234 listed wetlands (13 of which have formal transboundary plans) with the Global Peace Index, which ranks countries using 23 indicators, such as number of conflicts, conflict deaths, military expenditures, and relations with neighboring countries. The result is a prioritized list of countries most in need of tools of conflict resolution.

Working within the framework of the convention builds capacity between high-conflict-risk nations and has potential to develop otherwise-difficult-to-establish trust because the process is transparent and all stakeholder voices are heard. This can be important even when the existing conflict has nothing to do with international wetlands.

The convention is active in many countries with ongoing conflicts, such as Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iran, Iraq, and Sudan, and efforts there may help inform the ongoing debate as to the efficacy of conservation as a tool for peacemaking.

As environmental conditions continue to evolve rapidly, the need for institutions that can work in the transboundary environment will increase. The established international infrastructure of the convention has the potential to be a greater force in peacemaking. Further research may help focus on the strengths and weaknesses of the current system and reveal ways for more effective peacemaking efforts.

Suggestions for ways to enhance the convention’s role in environmental diplomacy include working more closely with researchers and practitioners directly involved in the environmental peacemaking field, increased focus on developing capacity for increased flexibility to react to dynamic conditions, and more active promotion of formal transboundary agreements.

Pamela Griffin is an independent scholar at IEDS where she focuses on the diplomatic potential of transboundary wetlands. -

Taking a Livelihoods Approach to Understanding Environmental Security

›February 17, 2012 // By Kate DiamondSince the concept of “environmental security” first gained traction in the early 1990s, research on the issue has been overwhelmingly focused on how environmental change impacts state security. That has been to the detriment of policymakers trying to preempt instability and conflict, according to the University of Toronto’s Tom Deligiannis in his article, “The Evolution of Environment-Conflict Research: Toward a Livelihood Framework,” published in February’s Global Environmental Politics.

-

‘Dialogue TV’ With Sharon Burke, Neil Morisetti, and Geoff Dabelko: Climate, Energy, and the Military

›We are entering “an emerging security environment” where “what constitutes a ‘threat’ and what constitutes a ‘challenge’” requires a broader understanding of security than has often been the norm, according to Sharon Burke, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Operational Energy Plans and Programs. Burke was joined by the UK’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti and ECSP’s Geoff Dabelko on a new installment of Dialogue TV. They debated what climate change and energy security mean for the world’s militaries.

-

Afghanistan and Pakistan: Demographic Siblings? [Part Two]

›February 15, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy MadsenLate last year, Afghanistan’s first-ever nationally representative survey of demographic and health issues was published, providing estimates of indicators that had previously been modeled or inferred from smaller samples. My first post on the survey focused on the methodology and results, which found that Afghanistan is not as much of a demographic outlier as many observers had assumed. But perhaps the most surprising finding is how the results compare to those of Afghanistan’s neighbor, Pakistan.

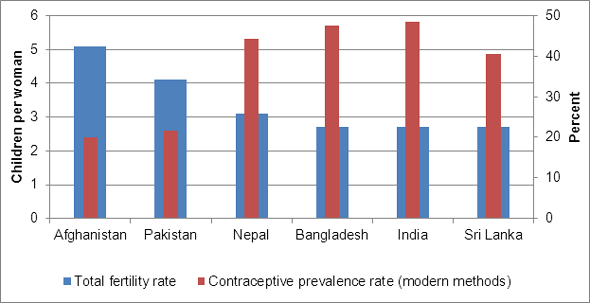

The political future of each country depends largely on the other and, with Afghanistan making progress on reproductive health issues that remain stalled in Pakistan, their demographic trajectories are heading toward closer synchronization as well. In one key measure – use of contraception among married women – Afghanistan is almost identical to Pakistan. The modern contraceptive prevalence rate is 19.9 percent, slightly lower than the rate of 21.7 percent in Pakistan.

While Pakistan faces its own serious political instability, it is widely regarded as more developed than its neighbor. Afghanistan is included in the UN’s grouping of least developed countries, and Pakistan is not. Pakistan’s GDP per capita is almost twice as high. On the surface, this should suggest lower fertility. There is a general negative relationship between economic development and fertility, though demographers are quick to point out its complexities, and David Shapiro and colleagues have found that countries with larger increases in GDP actually experience slower fertility declines.

Pakistan’s fertility rate of 4.1 children per woman is in fact 20 percent lower than Afghanistan’s, but the similarities in contraceptive use, which is one of the direct determinants of fertility, suggest that this gap could be shrinking. If Afghanistan’s median age at marriage (18 compared to 20 in Pakistan) was higher and more women were educated (76 percent of women have never been to school compared to 65 percent in Pakistan), the two fertility rates might be closer.

Pakistan’s Entrenched Challenge

Why are these indicators closer than might be expected? Relative to the other countries in South Asia, Pakistan has had considerably less success in promoting family planning use. Bangladesh has a per capita income about half that of India and one-quarter that of Sri Lanka, yet the three countries’ fertility rates are identical. Nepal has the lowest income in the region – even slightly below Afghanistan – yet more than 40 percent of married women use modern contraception and fertility is three children per woman. And then there is Pakistan. Despite a per capita income 90 percent that of India, only 22 percent of married women use modern contraception and fertility remains persistently high at over four children per woman.

The weaknesses of Pakistan’s family planning program have been well-documented. Government commitment has been lacking and cultural expectations and gender inequities are a powerful force to promote large family size. The country’s most recent DHS report cited disengagement with the program among local agencies, low levels of outreach into communities, and weak health sector support as likely causes for the stagnation of contraceptive use. In summer 2011, the Pakistani government abolished the federal Ministry of Health and empowered provincial governments with all responsibilities for health services. This transfer of authority could pay dividends by increasing local ownership of health care, but some in and outside Pakistan have raised concerns about the loss of regulatory oversight and information sharing entailed in total decentralization.

Compared to the Afghanistan survey, the most recent Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey provides more detail on women’s motivations and preferences regarding fertility and family planning. Overall, 55 percent of married women in Pakistan have a “demand” for family planning; that is, they wish to avoid pregnancy or report that their most recent pregnancy or birth was mistimed or unwanted. More than half of these women are using family planning, while the remaining 25 percent of married women have an “unmet need.”

Unintended pregnancies and births play a major role in shaping Pakistan’s demographic trajectory. The DHS survey finds that 24 percent of births occur earlier than women would like or were not wanted at all. If unwanted births were prevented, Pakistan’s fertility rate would be 3.1 children per woman rather than 4.1. Yet 30 percent of married women are using no contraceptive method and do not intend to in the future. The most common reasons for not intending to use family planning are that fertility is “up to God” and that the woman or her husband is opposed to it.

Linked Destinies

Just as Afghanistan and Pakistan’s political circumstances have become more entwined, their demographic paths are more closely in parallel than we might have expected. For Afghanistan, given the myriad challenges in the socioeconomic, political, cultural, and geographic environments, this is good news; for Pakistan, where efforts to meet family planning needs have fallen short of capacity, it is not. While Afghanistan is doing better than expected, Pakistan should be doing better.

Regardless, both countries are at an important juncture. With very young age structures and the attendant pressures on employment and government stability, each government must reduce unmet need for family planning or face mounting difficulties to providing for their populations in the future. In addition to rolling out health services, turning the share of women without education from a majority into zero would be an excellent way to start.

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and senior technical advisor at Futures Group.

Sources: Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health, Bongaarts (2008, 1978), Cincotta (2009), Embassy of Afghanistan, Haub (2009), International Monetary Fund, MEASURE DHS, Nishtar (2011), Population Action International, Savedoff (2011), Shapiro et al. (2011), UN-OHRLLS, UN Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau, The Washington Post.

Image Credit: Chart arranged by Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, data from MEASURE DHS. -

Political Demography: How Population Changes Are Reshaping International Security and National Politics (Book Launch)

›

“The world’s population is changing in ways that are historically unprecedented,” said Jack Goldstone, George Mason University professor and co-editor of the new book, Political Demography: How Population Changes Are Reshaping International Security and National Politics. [Video Below]

Showing posts from category security.