Showing posts from category population.

-

How Population Growth Is Straining the World’s Most Vital Resource

Turning Up the Water Pressure [Part Two]

›January 19, 2011 // By Russell SticklorThis article by Russell Sticklor appeared originally in the Fall 2010 issue of the Izaak Walton League’s Outdoor America magazine. Read part one here.

As concerns over water resources have grown around the globe, so too have proposed solutions, which range from common sense to absurd. Towing icebergs into the Persian Gulf or floating giant bags of fresh water across oceans to water-scarce countries are among the non-starters. But more moderate versions of those ideas are already being put into practice. These solutions showcase the power of human ingenuity — and reveal just how desperate some nations have become to secure water.

For example, India is doing business with a company out of tiny Sitka, Alaska, laying the framework for a water-export deal that could see huge volumes of water shipped via supertankers from the water-rich state of Alaska to a depot south of Mumbai. Depending on the success of this arrangement, moving bulk water via ship could theoretically become as commonplace as transoceanic oil shipments are today.

There is far greater potential, however, in harnessing the water supply of the world’s oceans. Perhaps more than any other technological breakthrough, desalination offers the best chance to ease our population-driven water crunch, because it can bolster supply. Although current desalination technology is not perfect, Eric Hoke, an associate professor of environmental engineering at the University of California-Los Angeles, told me via email, it is already capable of converting practically any water source into water that is acceptable for use in households, agriculture, or industrial production. Distances between supply and demand would be relatively short, considering that 40 percent of the world’s population — some 2.7 billion people — live within 60 miles of a coastline.

The Lure of Desalination

Although desalination plants are already up and running from Florida to Australia, the jury is still out on the role desalination can play in mitigating the world’s fresh water crisis. Concerns persist over the environmental impact seawater-intake pipes have on marine life and delicate coastal ecosystems. Another question is cost: Desalination plants consume enormous amounts of electricity, which makes them prohibitively expensive in most parts of the world. Desalination technology may not be able to produce water in sufficient scale — or cheaply enough — to accommodate the growing need for agricultural water. “Desalination is more and more effective [in producing] large quantities of water,” notes Laval University Professor Frédéric Lasserre in an interview. “But the capital needed is huge, and the water cost, now about 75 cents per cubic meter, is far too expensive for agriculture.” Although desalination might be “a good solution for cities and industries that can afford such water,” Lasserre predicts it “will never be a solution for agricultural uses.”

Nevertheless, desalination’s promise of easing future water crunches in populous coastal regions gives the technology game-changing potential at the global level. “Desalination technology,” Columbia University’s Upmanu Lall told said in an email, “will improve to the point that [water scarcity] will not be an issue for coastal areas.”

A Glass Half Full

With world population projected to grow by at least 2 billion during the next 40 years, water will likely remain a chief source of global anxiety deep into the 21st century. Because water plays such a fundamental role in everyday life across every society on earth, its shared stewardship may become an absolute necessity.

Take India and Pakistan’s landmark Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, which is still in effect today. The agreement — signed by two countries that otherwise can’t stand each other — shows that when crafted appropriately and with enough patience, international water-sharing pacts can help defuse tensions over water access before those tensions escalate into violence. Similar collaboration on managing shared waters in other areas of the world — a process that can be a bit bumpy at times — has proven successful to date.

Meanwhile, more widespread distribution of reliable family planning tools and services across Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia will also be needed if the international community hopes to meaningfully address water scarcity concerns. Better access to healthcare and family planning tools would empower women to take greater control over their reproductive health and potentially elevate living standards in crowded parts of the developing world. Smaller family sizes would help decelerate population growth over time, easing the burden on water and soil resources in many areas. The key is ensuring such efforts have adequate funding. The United States recently pledged $63 billion over the next six years through its Global Health Initiative to help partner countries improve health outcomes through strengthened health systems, with a particular focus on improving the health of women and children.

Putting a dent in the global population growth rate will be important, but it must be accompanied by a sustained push for conservation — nowhere more so than in agriculture. Investing in the repair of a leaky irrigation infrastructure could help save water that might otherwise literally slip through the cracks. Attention to maintaining healthy soil quality — by practicing regular crop rotation, for example — could also help boost the efficiency of irrigation water.

Setting a Fair Price

The most enduring changes to current water-use practices may have to come in the form of pricing. In most parts of the world, including parts of the United States, groundwater removal is conducted with virtually zero oversight, allowing farmers to withdraw water as if sitting atop a bottomless resource. But as groundwater tables approach exhaustion, the equation changes; as Ben Franklin famously pointed out, “when the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.”

The key, then, is to establish the worth of water before this comes to pass. Smart pricing could encourage conservation by making it less economical to grow water-intensive crops, particularly those ill-suited to a particular climate. “Some crops being grown should not be grown . . . once the true cost of water is factored in,” Nirvikar Singh, a University of California-Santa Cruz economics professor who focuses on water issues, told me via email. Pricing would also provide a revenue stream for modernizing irrigation infrastructures and maintaining sewage systems and water treatment centers, further bolstering water efficiency and quality both in the United States and around the globe.

To be sure, implementing a pricing scheme for water resources — which have been essentially free throughout history — will be unpopular in many parts of the world. It’s natural to expect some pushback from the public as water managers and governments take steps to address the 21st century water crunch. But given the resource’s undeniable and universal value on an ever-more crowded planet, few options exist aside from using the power of the purse to push for more efficient water use.

In the end, however, water pricing must be combined with greater public value on water conservation — we must not flush water down our drains before using it to its full potential. Whether that involves improving the water transportation infrastructure, recycling wastewater, taking shorter showers, or turning to less water-intensive plants and crops, steps big and small need to be taken to better conserve and more equitably divide the world’s water to irrigate our farms, grow our economies, and sustain future generations.

Sources: Columbia Water Center, National Geographic, Population Reference Bureau, White House.

Photo Credits: “Juhu Beach Crowded,” courtesy of flickr user la_imagen, and “Irrigation (China),” courtesy of flickr user spavaai. -

How Population Growth Is Straining the World’s Most Vital Resource

Turning Up the Water Pressure [Part One]

›January 18, 2011 // By Russell SticklorThis article by Russell Sticklor appeared originally in the Fall 2010 issue of the Izaak Walton League’s Outdoor America magazine.

For many Americans, India — home to more than 1.1 billion people — seems like a world away. Its staggering population growth in recent years might earn an occasional newspaper headline, but otherwise, the massive demographic shift taking place on our planet is out of sight, out of mind. Yet within 20 years, India is expected to eclipse China as the world’s most populous nation; by mid-century, it may be home to 1.6 billion people.

So what?

In a world that is increasingly connected by the forces of cultural, economic, and environmental globalization, the future of the United States is intertwined with that of India. Much of this shared fate stems from global resource scarcity. New population-driven demands for food and energy production will increase pressure on the world’s power-generating and agricultural capabilities. But for a crowded India, domestic scarcity of one key resource could destabilize the country in the decades to come: clean, fresh water.

Stepping Into a Water-Stressed Future

From Africa’s Nile Basin and the deserts of the Middle East to the arid reaches of northern China, water resources are being burdened as never before in human history. There may be more or less the same amount of water held in the earth’s atmosphere, oceans, surface waters, soils, and ice caps as there was 50 — or even 50 million — years ago, but demand on that finite supply is soaring.

Consider that since 1900, the world population has skyrocketed from one billion to the cusp of seven billion today, with mid-range projections placing the global total at roughly 9.5 billion by mid-century. And it only took 12 years to add the last billion.

Unlike the United States — which is a water-abundant country by global standards — India is growing weaker with each passing year in its ability to withstand drought or other water-related climate shocks. India’s water outlook is cause for alarm not just because of population growth but also because of climate change-induced shifts in the region’s water supply. Depletion of groundwater stocks in the country’s key agricultural breadbaskets has raised water worries even further. Water scarcity is not some abstract threat in India. As Ashok Jaitly, director of the water resources division at New Delhi’s Energy and Resources Institute, told me this past spring, “we are already in a crisis.”

How the country manages its water scarcity challenges over the coming decades will have repercussions on food prices, energy supplies, and security the world over — impacts that will be felt here in the United States. And India is not the only country wrestling with the intertwined challenges of population growth and water scarcity.

Transboundary Tensions

Several of the world’s most strategically important aquifers and river systems cross one or more major international boundaries. Disputes over dwindling surface- and groundwater supplies have remained local and have rarely boiled over into physical conflict thus far. But given the challenges faced by countries like India, small-scale water disputes may move beyond national borders before the end of this century.

Looming global water shortages, warns a recent World Economic Forum report, will “tear into various parts of the global economic system” and “start to emerge as a headline geopolitical issue” in the coming decades.

This has become a national security issue for the United States. Any country that cannot meet population-linked water demands runs the risk of becoming a failed state and potentially providing fertile ground for international terrorist networks. For that reason, the United States is keeping close track of how water relations evolve in countries like Yemen, Syria, Somalia, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. It is also one of the reasons water security is a key goal of U.S. development initiatives overseas. For instance, between 2007 and 2008, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) invested nearly $500 million across more than 70 countries to boost water efficiency, improve water treatment, and promote more sustainable water management.

More Mouths to Feed, Limited Land to Farm

Water is a critical component of industrial processes the world over — from manufacturing and mining to generating energy — and shapes the everyday lives of the people who rely on it for drinking, cooking, and cleaning. But the aspect of modern society most affected by decreasing water availability is food production. According to the United Nations, agriculture accounts for roughly 70 percent of total worldwide water usage.

Global population growth translates into tens of millions of new mouths to feed with each passing year, straining the world’s ability to meet basic food needs. Given the finite amount of land on which crops can be productively and reliably grown and the constant pressure on farms to meet the needs of a growing population, the 20th and early 21st centuries have been marked by periodic regional food crises that were often induced by drought, poor stewardship of soil resources, or a combination of the two. As demographic change continues to rapidly unfold throughout much of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the ability of farmers and agribusinesses to keep pace with surging food demands will be continually challenged. Food shortages could very well emerge as a staple of 21st century life, particularly in the developing world.

Mirroring the growing burden on farmland will be a growing demand for water resources for agricultural use — and the outlook is not promising. According to a report from the International Water Management Institute in Sri Lanka, “Current estimates indicate that we will not have enough water to feed ourselves in 25 years’ time.”

As one of the world’s largest agricultural producers, the United States will be affected by this food crisis in multiple ways. Decreased food security abroad will increase demand for food products originating from American breadbaskets in California and the Midwest, possibly resulting in more intensive (and less sustainable) use of U.S. farmland. It may also drive up prices at the grocery store. Booming populations in east and south Asia could affect patterns of global food production, particularly if severe droughts spark downturns in food production in key Chinese or Indian agricultural centers. Such an outcome would push those countries to import huge quantities of grain and other food staples to avert widespread hunger — a move that would drive up food prices on the global market, possibly with little advance warning. Running out of arable land in the developing world could produce a similar outcome, Upmanu Lall, director of the Columbia Water Center at Columbia University, said via email.

Changing Tastes of the Developing World

Economic modernization and population growth in the developing world could affect global food production in other ways. In many developing countries, rising living standards are prompting changes in dietary preferences: More people are moving from traditional rice- and wheat-based diets to diets heavier in meat. Accommodating this shift at the global level results in greater demand on “virtual water” — the amount of water required to bring an agricultural or livestock product to market. According to the World Water Council, 264 gallons of water are needed to produce 2.2 pounds of wheat (370 gallons for 2.2 pounds rice), while producing an equivalent amount of beef requires a whopping 3,434 gallons of water.

In that way, the growing appeal of Western-style, meat-intensive diets for the developing world’s emerging middle classes may further strain global water resources. Frédéric Lasserre, a professor at Quebec’s Laval University who specializes in water issues, said in an interview about his book Eaux et Territories, that at the end of the day, it simply takes far more water to produce the food an average Westerner eats than it does to produce the traditional food staples of much of Africa or Asia.

Continue reading part two of “Turning Up the Water Pressure” here.

Sources: Columbia Water Center, ExploringGeopolitics.org, International Water Management Institute (Sri Lanka), Population Reference Bureau, The Energy and Resources Institute (India), United Nations, USAID, World Economic Forum, World Water Council.

Photo Credits: “Ganges By Nightfall,” courtesy of flickr user brianholsclaw, and “Traditional Harvest,” courtesy of flickr user psychogeographer. -

Andrew Morton, UNEP

Haiti 2011: Looking One Year Back and Twenty Years Forward

›January 14, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThis piece first appeared on the website of the Haiti Regeneration Initiative – a new collaborative venture between the UN, the government of Haiti, the Earth Institute at Columbia University, Catholic Relief Services, and a wide range of other implementing partners.

In 2010, Haiti endured a year like no other. The country was struck by a devastating earthquake, a cholera epidemic, floods, violence, and political uncertainty. At the same time, Haiti witnessed heroic rescue and relief efforts and an enormous demonstration of international goodwill. Today, recovery and reconstruction are taking place, albeit at a frustratingly slow pace and not currently at the scale of existing needs.

Just as importantly, 2010 brought a renewed awareness of the need for lasting solutions and improvements in the design and delivery of international aid. During the next few days, we will look back on the tragic events of January 12th, 2010, while at the same time, we must look forward, not just one year, but 20.

A Failed Recovery in a Fragile State

Already before the earthquake, Haiti was a fragile state trapped in a slow but vicious negative spiral. A tightly interconnected trio of chronic environmental, political, and socio-economic crises has gradually ensured that Haiti has had the lowest human development indicators in the Western Hemisphere, with life-long poverty, chronic hunger, and violence. Catastrophic events, such as natural disasters, epidemics, and political violence, have simply steepened the descent. Moreover, disaster recovery efforts to date have systematically failed to bring the country back to pre-disaster levels.

In spite of this depressing analysis and forecast, we should not resign ourselves to failure. The situation can be turned around but only with great effort and by foregoing “business as usual.”

The first step towards change is full recognition of the situation. In the case of Haiti, this means recognizing the marked failure of foreign recovery and development assistance to date. It is pointless to blame any particular institution or individual for this: The current state of Haiti is the culmination of generations of efforts and decisions, good and bad, combined with rapid population growth and an inherent vulnerability to natural hazards. (Editor’s note: according to the UN, Haiti’s fertility rate tripled in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake last year.)

The second step is planning. While relatively solid recovery plans have been developed by the government of Haiti with international assistance, their implementation has not so far met with success, due to four interlinked problems.

First, the humanitarian imperative for urgent and chronic relief is overrunning all good intentions for recovery and development – it is politically impossible, inhumane, and simply unwise to ignore the basic resource needs of a cholera epidemic and a million people living in tents.

Second, nothing suppresses development investments like political violence and uncertainty: Few donors, and even fewer companies, will invest while riots and political uncertainty paralyze the country and destroy its reputation.

Third, the planning process is necessarily democratic and participatory; as a result, however, virtually all of the country’s needs are listed with no reliable process of thematic or geographic prioritization.

Finally – and perhaps most importantly – although the plans are official and uncontested, they generally lack broad credibility and commitment. Weary aid workers, government officials, donors and the general public look back at the fate of previous plans and, not surprisingly, expect these latest efforts to fail just as others have before.

Regenerating Haiti

Unlike virtually all other aid organizations I have met in Haiti, the team behind the Haiti Regeneration Initiative (HRI) has fortunately been given the vital time and seed funding to reflect on these issues and try something really different. After two years of preparation, on January 4, 2010, we launched a long-term rural sustainable development initiative for the southwestern tip of Haiti. The Côte Sud Initiative aims to transform the lives and the degraded environment of 200,000 people living in one of the poorest yet most beautiful parts of Haiti.

This specific initiative will only directly assist two percent of the population of Haiti, but just as importantly, we aim to demonstrate that sustainable development is truly possible in this country. Because national-scale issues require national-scale efforts, we also aim to promote change through dialogue and assisting the government of Haiti to develop and deliver on sustainable development plans that work. This is the primary mission of the HRI.

We must arrest the long-term decline as soon as possible. This includes, but is not limited to, basic recovery from the earthquake. At the same time, we need to establish the foundations for the long-term radical changes that are an absolute prerequisite to achieving sustainable development in Haiti. We must prepare to turn the vicious circles into virtuous ones.

So what are the short- to medium-term priorities?

The first is political stabilization, as vital foreign aid and direct foreign investment will simply not arrive in the face of such negative news and uncertainty.

Second, a massive aid investment in potable water and sanitation is required to suppress cholera in the longer term. No country can develop in the midst of recurrent major epidemics. This investment needs to be designed for sustainability; in other words, infrastructure needs to be accompanied by realistic, locally financed mechanisms for maintenance. Otherwise it will become useless within weeks of installation.

Third, persistence is needed on the current debris clearance and rebuilding efforts; we know from many other countries that such efforts can take years to be completed.

Finally, development aid should move out of Port-au-Prince and into the regions. In 2010, the massive influx of earthquake relief and reconstruction aid actually increased the economic pull of the capital and exacerbated existing urban problems.

What to do to prepare for the long term? Implementing radical change requires political support and even cultural reform, so in addition to good ideas, the HRI partnership will work hard to develop a sense of national ownership of the solutions as well as the problems.

Many of the ideas are not new: mildly decentralized development, diversified and value-added agriculture, niche tourism, improved aid coordination, public-private partnerships, etc.

Many, however, are radical, including a proposed paradigm change on migration and remittances, education, food security and import policies, widespread privatization, harsh revisions and rebuttals of traditional development models and assumptions, and adaptation to the new types of religious NGOs. These are just a few of the concepts and opportunities we have identified and will work to make a reality in Haiti.

Over the next few years, the HRI hopes to foster an intelligent and useful dialogue on sustainable development in Haiti. We look forward to having all of those who are concerned about and interested in helping Haiti join us in the debate.

Andrew Morton is the Haiti Regeneration coordinator and a senior staff member at UNEP. For more information on the Haiti Regeneration Initiative please see www.haitiregeneration.org.

Sources: BBC, Haiti Regeneration Initiative, United Nations Development Programme.

Image Credit: “Rebuilding as a community,” courtesy of flickr user Save the Children. -

Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts: Quantifying the Integration of Population, Health, and Environment in Development

›It makes intrinsic sense that integrated approaches working across development sectors are a good thing – especially when it comes to the complex issues facing people in developing countries and the environment in which they live. After all, integration avoids overlap and redundancies, and adds value to results on the ground. Yet, quantifying the benefit of integration has been difficult and to date, little on this topic has been published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Not anymore. Our article, “Integrated management of coastal resources and human health yields added value: a comparative study in Palawan (Philippines),” recently published in the journal Environmental Conservation, breaks new ground. Rigorous time-series data and regression analysis document evidence of different disciplines working together to produce synergies not obtainable by any one of the disciplines alone.

The article presents quasi-experimental research recently conducted in the Philippines that tested the hypothesis that a specific model of integration – one in which family planning information, advocacy, and service delivery were integrated with coastal resources management – yields better results than single-sector models that provide only family planning or coastal resources management services.

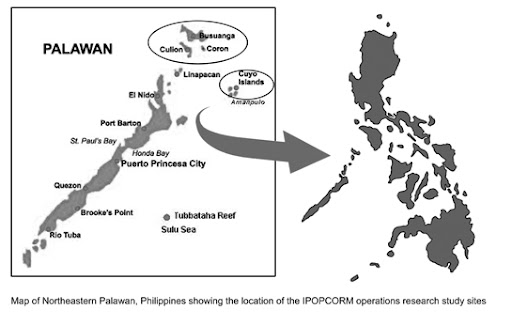

The study collected data from three island municipalities in the Palawan region of the Philippines, where the residents are dependent on coastal resources for their livelihoods. The integrated model was implemented in one municipality, while the single-sector models (one coastal resource management program and one reproductive health management program) were conducted in two separate municipalities.

The results of the study provide strong evidence that the integrated model outperformed the single-sector models in terms of improvements in coral reef and mangrove health; individual family planning and reproductive health practices; and community-level indicators of food security and vulnerability to poverty. Young adults – especially young men – at the integrated site were more likely to use family planning and delay early sex than at the sites where only family planning and reproductive health interventions were provided.

Coral reef health – as measured by a composite condition index – and mangrove health increased significantly at the integrated site, compared to the site where only coastal resource management interventions were provided. Data from the integrated site also showed a significant decline in the number of full-time fishers, as well as fewer people who knew someone that used cyanide or dynamite to fish – both factors that amplify a community’s vulnerability to food insecurity. Finally, the proportion of young people with income below the poverty threshold decreased by a significant margin in areas where the integrated population and coastal resources management (IPOPCORM) model was applied.

Let’s hope this research is just the beginning of a more thoughtful and effective approach to meeting multiple development goals in a lasting mannerEducational activities at the integrated site focused on illuminating the intrinsic relationship between fast-growing coastal communities in the Philippines and the diminishing health of the coral reefs and fisheries that they depend on for food and livelihoods. Community change agents, often fishermen and their families, talked to their neighbors and fellow fishers about the importance of planning and spacing families and establishing and respecting marine reserves to protect the supplies of food from the sea. They referred those interested in family planning to community-based social marketers of contraceptives or the nearest health center for other services.

These same community members also participated in activities to sustainably manage their coastal resources: working with local government officials to establish marine reserves, replant mangroves, serve as community fish wardens to patrol those reserves, test out alternative livelihoods such as seaweed farming, and start small businesses to diversify their income and reduce fishing pressure.

Development professionals should pay close attention to the conclusions of this study. In environmentally significant areas where human population growth is high, it will be difficult to sustain conservation gains without parallel efforts to address demographic factors and inequities in the distribution of health and family planning services. Integrating responses to population, health, and environment (PHE) issues provides an opportunity to address multiple stresses on communities and their environments and, as this study demonstrates, adds value in such a way that significantly improves community resilience and other outcomes.

This research allows those of us who believe strongly in integrating population, health, and environment programming to point to quantitative proof that the approach works. We now need to expand PHE programming to reach more people in other parts of the world where communities face a similar nexus of challenges. New initiatives have started taking the lessons from this research, applying them to new contexts in Africa and Asia, and scaling them up to reach many more in the Philippines.

Let’s hope this research is just the beginning of a more thoughtful and effective approach to meeting multiple development goals in a lasting manner in the places that need it most.Leona D’Agnes is the technical director of IPOPCORM, Joan Castro is the executive vice president of PATH Foundation Philippines Inc, and Heather D’Agnes is the Population, Health, Environment Technical Advisor in the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Office of Population and Reproductive Health.

Sources: BALANCED, Link TV, PATH Foundation Philippines Inc., World Wildlife Foundation.

Image Credit: Philippines village (adapted) and municipalities map courtesy of PATH Foundation Philippines Inc. -

Women and Climate Change

›A new Worldwatch Institute report, “Population, Climate Change, and Women’s Lives,” by Robert Engelman, discusses the relationship between women’s equality and climate change. Slowing population growth will reduce greenhouse gas emissions and help societies adapt to climate change, says Engelman. What’s more, this can only be done through an investment in women’s rights and education. Population change comes primarily through reducing unintended pregnancies by offering men and women access to family planning services, improving education for all (especially girls and women), and promoting full gender equality. “Population change should be viewed as one element of the historic effort to bring women into equal standing with men,” writes Engelman.

A recent report by Scott Moreland, Ellen Smith, and Suneeta Sharma of the Futures Group analyzes just what the impact of meeting the unmet need for family planning would be on global population growth. Looking at 99 developing countries and the United States, the report, titled World Population Prospects and Unmet Need for Family Planning, found that by gradually meeting the global demand for family planning, population would be reduced to 6.3 billion people by 2050, below current world population and well below the UN medium fertility variant prediction, which is derived from past trends but does not take into account meeting unmet need for family planning. Meeting this need would only cost $3.7 billion more per year than the UN medium fertility variant scenario and less than the low scenario. $1.4 billion of this would cover the unmet demand in the United States. -

Bringing PHE to a Muslim Community in Tanzania

Abdalah Overcomes the Odds

›This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project.

“Now, people can plan their families and know how to use a condom,” says Abdalah Masingano as he proudly tells how his community has come to accept integrated population, health, and environment (PHE) activities.

The 35 year-old Abdalah is a PHE provider. He lives near the Saadani National Park (SANAPA) — one of Tanzania’s newest, and the only terrestrial park with a contiguous marine area in southeastern Tanzania. Saadani is home to the rare Roosevelt Sable antelope and the nesting grounds for several endangered species of marine turtles. One of the largest threats to biodiversity in this area is the clearing of mangroves and coastal forests for firewood and charcoal-making. About 95 percent of households in the area depend on firewood for cooking and most use a three-stone fireplace that utilizes only about 10 percent of its energy potential. These are just some of many pressures that people living around the park place on the biodiversity-rich forest and marine resources of the area.

Abdalah and his 31 year-old wife have two children: a 14-year-old boy and a six-year-old girl. His wife has been on the pill for four years. For two years now, Abdalah has been selling condoms in his village store. He made this decision for simple reasons. He saw that people needed condoms for both family planning and health, and he had come to understand the linkages between the behaviors of people living in the area and the health of the environment.

Abdalah gained this understanding when he was recruited to become a PHE provider by the Tanzania Coastal Management Partnership as part of its work through the USAID-supported BALANCED Project, which is promoting PHE implementation in biodiversity-rich countries. In a two-day training, Abdalah learned about integrated PHE and the links between population (family planning), health, and the environment. He has been educating villagers ever since.

“In the past, it was difficult for people to plan their families because they were embarrassed,” recalls Abdalah. As a PHE provider, Abdalah delivers integrated PHE messages to his fellow villagers. After attending the BALANCED training, Abdalah learned that promoting family planning makes sense for reasons beyond health. Forest and marine resources found both around and inside the Saadani are heavily exploited by local villages – and from a biodiversity conservation perspective, reducing population pressures is just one critical step in protecting this biodiversity.

When people visit his shop, Abdalah takes the opportunity to explain the population and environment connection. Because deforestation is a particular problem in the area where Abdalah lives and works, he promotes the use of fuel-efficient stoves.

Showcasing his own stove, his explains that by using a simple clay stove – which is made locally – a household can save almost 1.5 tons of fuelwood annually and reduce by 50 percent the time women spend collecting fuelwood. At the same time, he reminds villagers that when they plan their families they help keep mothers and children healthy. Healthier families also tend to put fewer pressures on – and thus keep healthier – the very natural resources they depend on for food and income.

Initially, Abdalah’s Muslim neighbors were unhappy with him promoting family planning and condom use. They believed what he was doing encouraged sex and prostitution. “They thought I was lost,” he explains smiling. Fortunately, his wife has been very supportive of him despite the discouraging reactions of his fellow villagers early on in his efforts.

Today, Abdalah’s perseverance has paid off. He now sells more than 200 condoms monthly and takes the time to demonstrate to his customers how to use them properly. When there is the opportunity, he also refers his customers to the local health dispensaries for additional family planning services and commodities. Abdalah believes people respect him now. “I feel good because I am able to help,” he concludes. That “help” impacts both the health and well-being of his fellow villagers and the health and well-being of the environment. Abdalah and his wife plan to have their third child two years from now.

This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project. A PDF version can be downloaded from the PHE Toolkit. PHE Champion profiles highlight people working on the ground to improve health and conservation in areas where biodiversity is critically endangered.

Sources: Darfur Stoves Project, IPS News, TSN Daily News, UN.

Photo Credit: Abdalah showing a box of condoms for sale in his small shop by Juma Dyegula, courtesy of the BALANCED Project. -

Peter Gleick on Peak Water

› “The purpose of the whole debate about peak water is to help raise awareness about the nature of the world’s water problems and to help drive toward solutions,” says the Pacific Institute’s Peter Gleick. But Gleick asserts that in the same way certain countries have been contending with “peak oil” concerns in recent years, they may soon also have to deal with “peak water” as well.

“The purpose of the whole debate about peak water is to help raise awareness about the nature of the world’s water problems and to help drive toward solutions,” says the Pacific Institute’s Peter Gleick. But Gleick asserts that in the same way certain countries have been contending with “peak oil” concerns in recent years, they may soon also have to deal with “peak water” as well.

Unlike oil, water is largely a renewable resource, but countries in Asia, the Middle East, and elsewhere are pumping groundwater faster than aquifers can replenish naturally. Gleick explains “there will be a peak of production in many of those places and eventually the food that we grow with that water or the widgets that we make from the factories that use that water will be nonsustainable and production will have to drop.”

The world’s surface and groundwater resources can be used sustainably even in the face of continued global population growth, says Gleick, but only “if we are careful about the ecological consequences and the efficiency with which we use it.” However, to date, he says, “those issues have not adequately been brought into the discussion about water policy.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

Water as a Strategic Resource in the Middle East

‘Clear Gold’ Report From CSIS

›“The real wild-card for political and social unrest in the Middle East over the next 20 years is not war, terrorism, or revolution – it is water,” begins the CSIS Middle East Program’s latest report, Clear Gold: Water as a Strategic Resource in the Middle East, by Jon B. Alterman and Michael Dziuban.

The authors contend that with growing populations, groundwater depletion, not the more traditional questions about transboundary river governance, poses a “more immediate and strategically consequential challenge,” particularly because many Middle Eastern governments have deflated the true cost of water to help spur growth and garner popularity.

In the accompanying video feature above, much-troubled Yemen is outlined as one of the most at-risk countries for water-induced instability. The narrator notes that “with Yemen’s population growing fast and almost half of agricultural water going towards the narcotic leaf qat instead of food, experts think that Sanaa [the capital] could run out of water in seven years or less and the rest of the country may not be far behind.”

In an interview with Reuters in 2008, Yemeni Water and Environment Minister Abdul-Rahman al-Iryani said the country’s burgeoning water crisis is “almost inevitable because of the geography and climate of Yemen, coupled with uncontrolled population growth and very low capacity for managing resources.”

Yemen is a particularly abject example because water availability is only one contributor in a long list of domestic problems, including a large youth population, gender inequity, immigration from the Horn of Africa, corruption, ethnic tensions, and terrorism.

The narrator concludes that “Yemen is the most worrisome example but clearly not the only one.” Alterman and Dziuban also point to Jordan and Saudi Arabia as states vulnerable to groundwater depletion.

For more on the Middle East’s current and future environmental security issues, be sure to check out The New Security Beat’s “Crossroads” series, with features on Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

Video Credit: “Clear Gold: Water as a Strategic Resource in the Middle East,” courtesy of CSIS.