-

Food Price Shocks and Instability Highlight Weaknesses in Governance and Markets

›

Unrest across the Middle East has been front-page news for weeks, with commentators searching for explanations to account for the shifting political winds. Many, such as Thomas Friedman and Kevin Hall, have drawn connections between food prices and instability. But, as they point out, high food prices do not deterministically lead to unrest. Instead, rising prices highlight the degree to which governments and governance processes provide and ensure sustainable livelihoods for their people. What these and other commentators point to is that recognizing the role of government in providing food and security is vital: high food prices, they argue, don’t directly cause unrest, but high food prices in poorly managed countries creates a dangerous environment in which unrest may be more likely.

-

First Steps on Human Security and Emerging Risks

›The 2010 Quadrennial Development and Diplomacy Review (QDDR), the first of its kind, was recently released by the State Department and USAID in an attempt to redefine the scope and mission of U.S. foreign policy in the 21st century. Breaking away from the Cold War structures of hard international security and an exclusive focus on state-level diplomacy, the QDDR recognizes that U.S. interests are best served by a more comprehensive approach to international relations. The men and women who already work with the U.S. government possess valuable expertise that should be leveraged to tackle emerging threats and opportunities.

-

Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty?

›The much-anticipated Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review(QDDR) demands to be taken seriously. Its hefty 250 pages present a major rethink of both American development policy and American diplomacy. Much of it is to be commended:

-

Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts: Quantifying the Integration of Population, Health, and Environment in Development

›It makes intrinsic sense that integrated approaches working across development sectors are a good thing – especially when it comes to the complex issues facing people in developing countries and the environment in which they live. After all, integration avoids overlap and redundancies, and adds value to results on the ground. Yet, quantifying the benefit of integration has been difficult and to date, little on this topic has been published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Not anymore. Our article, “Integrated management of coastal resources and human health yields added value: a comparative study in Palawan (Philippines),” recently published in the journal Environmental Conservation, breaks new ground. Rigorous time-series data and regression analysis document evidence of different disciplines working together to produce synergies not obtainable by any one of the disciplines alone.

The article presents quasi-experimental research recently conducted in the Philippines that tested the hypothesis that a specific model of integration – one in which family planning information, advocacy, and service delivery were integrated with coastal resources management – yields better results than single-sector models that provide only family planning or coastal resources management services.

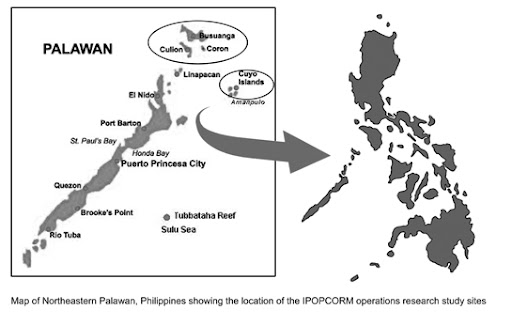

The study collected data from three island municipalities in the Palawan region of the Philippines, where the residents are dependent on coastal resources for their livelihoods. The integrated model was implemented in one municipality, while the single-sector models (one coastal resource management program and one reproductive health management program) were conducted in two separate municipalities.

The results of the study provide strong evidence that the integrated model outperformed the single-sector models in terms of improvements in coral reef and mangrove health; individual family planning and reproductive health practices; and community-level indicators of food security and vulnerability to poverty. Young adults – especially young men – at the integrated site were more likely to use family planning and delay early sex than at the sites where only family planning and reproductive health interventions were provided.

Coral reef health – as measured by a composite condition index – and mangrove health increased significantly at the integrated site, compared to the site where only coastal resource management interventions were provided. Data from the integrated site also showed a significant decline in the number of full-time fishers, as well as fewer people who knew someone that used cyanide or dynamite to fish – both factors that amplify a community’s vulnerability to food insecurity. Finally, the proportion of young people with income below the poverty threshold decreased by a significant margin in areas where the integrated population and coastal resources management (IPOPCORM) model was applied.

Let’s hope this research is just the beginning of a more thoughtful and effective approach to meeting multiple development goals in a lasting mannerEducational activities at the integrated site focused on illuminating the intrinsic relationship between fast-growing coastal communities in the Philippines and the diminishing health of the coral reefs and fisheries that they depend on for food and livelihoods. Community change agents, often fishermen and their families, talked to their neighbors and fellow fishers about the importance of planning and spacing families and establishing and respecting marine reserves to protect the supplies of food from the sea. They referred those interested in family planning to community-based social marketers of contraceptives or the nearest health center for other services.

These same community members also participated in activities to sustainably manage their coastal resources: working with local government officials to establish marine reserves, replant mangroves, serve as community fish wardens to patrol those reserves, test out alternative livelihoods such as seaweed farming, and start small businesses to diversify their income and reduce fishing pressure.

Development professionals should pay close attention to the conclusions of this study. In environmentally significant areas where human population growth is high, it will be difficult to sustain conservation gains without parallel efforts to address demographic factors and inequities in the distribution of health and family planning services. Integrating responses to population, health, and environment (PHE) issues provides an opportunity to address multiple stresses on communities and their environments and, as this study demonstrates, adds value in such a way that significantly improves community resilience and other outcomes.

This research allows those of us who believe strongly in integrating population, health, and environment programming to point to quantitative proof that the approach works. We now need to expand PHE programming to reach more people in other parts of the world where communities face a similar nexus of challenges. New initiatives have started taking the lessons from this research, applying them to new contexts in Africa and Asia, and scaling them up to reach many more in the Philippines.

Let’s hope this research is just the beginning of a more thoughtful and effective approach to meeting multiple development goals in a lasting manner in the places that need it most.Leona D’Agnes is the technical director of IPOPCORM, Joan Castro is the executive vice president of PATH Foundation Philippines Inc, and Heather D’Agnes is the Population, Health, Environment Technical Advisor in the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Office of Population and Reproductive Health.

Sources: BALANCED, Link TV, PATH Foundation Philippines Inc., World Wildlife Foundation.

Image Credit: Philippines village (adapted) and municipalities map courtesy of PATH Foundation Philippines Inc. -

Civil-Military Interface Still Lacks Operational Clarity

›The Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) is an important first step in redefining civilian roles and capacities in crises, conflict, and instability. After the expensive failures of both the military and USAID in Vietnam during the 1960s and 70s, Congress set new guidelines governing military interventions and assistance to foreign governments. Foreign assistance staff was cut from 15,000 to 2,000 people. When modern-day conflicts arose and USAID found itself understaffed and under-funded, the military was called upon to fill a gap and became overnight, in essence, our primary development agency.

-

The Cholera Quandary

›The original version of this article first appeared in the Stimson Center Spotlight series, November 19, 2010.

Cholera is usually seen as one of the most devastating infections of the 19th century. Trade routes carried cholera from India to the great cities of Europe and the United States. Disease, fear, and political unrest spread in great waves that cost millions of lives. After much destruction, it was only with science and resources that certain populations were able to curb the epidemic.One of the most celebrated lessons in the history of public health involves a cholera outbreak in London in 1854 and efforts by John Snow – celebrated as the father of epidemiology – to control it. At the time, it was not clear that cholera was a waterborne bacterial infection that caused severe diarrhea and vomiting, and sometimes fatal dehydration. Snow proved that the outbreaks decimating communities spread from contaminated water. Water and sanitation services had virtually eliminated cholera epidemics in the developed world by the early 1900s.

Today, cholera has been nearly eradicated in the developed world, but continues to be endemic in poorer countries. Risks seem to be rising as larger populations are crowded into unsanitary conditions. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates three to five million illnesses and 100,000-200,000 deaths from cholera each year. If caught early, infections are treatable with inexpensive oral rehydration solutions. For much of the world, these options are unavailable or underused – the mere presence of cholera serves as an indicator of a country’s socioeconomic status and health system capabilities.

The cholera epidemics that are currently menacing countries on three different continents – Asia, Africa, and North America – raise tough questions about what is required to protect the world’s vulnerable populations. We know how to predict the crisis of cholera, prevent outbreaks, and contain them when they occur. To control cholera, what is needed is not cutting-edge technologies, but will, transparency, and resources – and where cholera appears, at least one of these three factors has failed.

Currently, cholera outbreaks in Pakistan, Haiti, and Nigeria are piling misery upon misery. Cholera in post-flood Pakistan comes as no surprise. When floodwaters left millions homeless and without access to clean drinking water in a region where cholera remains endemic, health officials could have reasonably assumed infected human waste would seep into water supplies and spread disease. The inability of health networks on the ground to prevent and then detect cholera demonstrates cracks in the country’s health system. What is apparent here is a lack of will and resources. Disease surveillance is especially vital in a post-disaster scenario where steps can be taken, such as treating water with chlorine, to prevent an outbreak.

Haiti had been free of cholera for at least 50 years, but the disease struck and spread rapidly 10 months after the devastating January 2010 earthquake. It reached Haiti’s capital and spread to its neighbor, the Dominican Republic. Since October, more than 114,000 people have become ill and more than 2,500 have died (Editor’s note: updated since original publication).

Haiti lacked resources for basic infrastructure even prior to the earthquake; the cholera crisis is not only costing lives, but also diverting aid from “building back better.” But regardless of the source of the cholera strain, if basic infrastructure and resources to protect Haiti’s vulnerable populations had been in place, cholera’s re-emergence would have been far less devastating.

This particular outbreak draws attention to the practical and political challenges of identifying health risks in humanitarian workers and peacekeepers, many of whom come from developing countries themselves. Evidence suggests that peacekeepers from Nepal, housed at a UN base, may have been the source of the outbreak clustered around the Artibonite River. Cholera outbreaks frequently exacerbate frictions between communities and aid workers – suspicions that have led to riots and murder more than once in recent years. At least two people were killed in Haiti in riots with peacekeepers during November.The delayed decision by the UN to investigate whether the outbreak originated with peacekeepers may have conserved resources for the race to stave off more cases, but did little to build trust between communities and foreign workers. Further violence and protests surrounding the recent disputed presidential election in Haiti do little to ease the devastation and in fact, threaten the relief effort. There has been discussion in Congress of cutting direct aid and suspending visas for Haitian officials until the dispute as been resolved. The Organization of American States is now reviewing the results.

In Africa, Nigeria is experiencing its worst cholera outbreak since 1991, and the disease is crossing borders. An onslaught of cases raised the 2010 death toll to more than 1,500 fatalities out of 40,000 cases. This mortality rate is three times higher than the seasonal cholera outbreaks of 2009, and seven times higher than 2008. Despite Nigeria’s oil wealth, most of the population is impoverished. Two-thirds of rural Nigerians lack access to safe drinking water and fewer than 40 percent of people in cholera-affected areas have access to toilet facilities, according to the Nigerian Health Ministry. A combined lack of will, transparency, and resources mean that cholera epidemics occur annually, and in clusters throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

A century and a half after John Snow’s discovery, we know how to control cholera. Globally, the resources exist, but the question of a collective will remains. For those who lack clean water to drink, to wash, or even proper toilets, the gap between knowing and doing is not easily closed. The international community has shown repeatedly that it can confront cholera outbreaks like those in Haiti, Pakistan, and Nigeria in the midst of crisis. The question remains as to how those efforts can eliminate the conditions that fostered outbreaks in the first place. The answer is not as riveting as the causes that often receive funding: basic infrastructure and resources. Roads, wells, clean water, toilets, education, and the willingness to recognize that if the foundation is not sound, nothing will be able to stand. Sometimes the simplest problems are the most difficult to solve.

Sarah Kornblet is a research fellow at the Global Health Security Program at the Stimson Center. Her research focuses on the International Health Regulations, health systems strengthening, global health diplomacy, the intersection of public health and security, and the potential for innovative and dynamic health policy solutions in developing countries.

Sources: Agence France-Presse, BBC, Washington Post, World Health Organization.

Photo Credit: “UN Peacekeepers Provide Security During Port-au-Prince Food Distribution,” courtesy of flickr user United Nations Photo. -

From Cancun: Getting a Climate Green Fund

›Over 9,000 negotiators from 184 countries have gathered for the 16th Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known as COP-16, in Cancun, Mexico. No one expects a binding emissions reduction agreement, but a successful outcome on a set of decisions here – the so-called “balanced package” – will help build trust among countries and make progress towards a final emissions agreement next year.

One of the most important parts of the package is agreement on the creation of a green climate fund – an international fund designed to help developing countries adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change.

If the negotiations are as successful, as expected, the fund will be part of a package that also includes the architecture for an adaptation body, technology transfer, REDD-plus, and progress towards a binding international mitigation agreement that negotiators hope to conclude at COP-17 in Durban, South Africa.

An event Monday morning co-hosted by Oxfam and the Global Campaign for Climate Action, featured a variety of developed and developing country perspectives about what a new fund for mitigation and adaptation programs should look like.

The event was galvanized by a letter, currently being circulated here at the talks, signed by 215 civil society organizations and calling for “the establishment of a fair global climate fund at COP-16 that will meet the needs and interests and protect the rights of the most vulnerable communities and people around the world.” In opening comments and a question-and-answer session, panelists articulated some of the most contentious points that negotiators are currently discussing, some of the reasons why a green fund is so important, and the implications for global equity, sustainable development, and international security.

A main point under discussion right now is how the fund will be governed. The United States and other developed countries argue that the fund should work under the supervision of the UNFCCC but international financial institutions, like the World Bank, should also assist in creating the fund.

Judith McGregor, the UK ambassador to Mexico, argued in her opening statement that for the United Kingdom, “climate finance… is a clear, clear priority” at the COP, but that the World Bank would lend the fund legitimacy and make donors more confident in the fund’s ability to deliver. Tim Gore from Oxfam expressed the opinion held by many civil society organizations and delegates from developing countries, that the fund must “act under the authority of the UNFCCC… independent from institutions such as the World Bank,” because a new climate fund should have an equitable governance structure that includes the voices of developing countries, civil society members, indigenous peoples, women, and other stakeholders – not a majority share by the developed countries like at the World Bank.

Another stumbling block is how climate finance will be divided between adaptation and mitigation programs. Gore argued that adaptation and mitigation finance must be balanced 50-50, whereas currently “there is a huge adaptation gap… less than 10 percent of current climate finance is going to adaptation.” Evans Njewa, the lead finance negotiator representing the group of Least Developed Countries (LDCs), noted in his statement that “adaptation is the priority for the LDCs [in Cancun].”

The source of these funds is also a contentious issue that divides developed and developing countries. Under the Copenhagen Accord, most of the COP country parties agreed that developed countries would mobilize $30 billion in fast start finance by 2012 and $100 billion per year by 2020 in climate finance from public, private, and other “innovative sources,” such as a carbon tax or cap-and-trade systems. Developed countries like the United States are mobilizing public funds for climate finance but argue that the majority of the $100 billion figure should be provided by private investments and that loans provided by development institutions as well as grants should also count.

Climate finance for adaptation will help make poor, rural communities in particular more resilient to the effects of climate change, including drought, floods and tropical storms, and therefore help the international community to achieve several related development milestones such as the Millennium Development Goals, according to Alzinda Abrea, finance minister of Mozambique.

Cate Owen of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) explained that investing in climate adaptation now “makes good sense” because “investing now in responding to climate change will lessen the long-term costs” to developed country donors.

The message that climate adaptation measures are becoming essential to sustainable development was perhaps delivered most forcefully by Florina Lopez, an indigenous person from Panama, who described the impacts that her people are already suffering as a result of climate change. Since her community survives by fishing, hunting and growing crops, severe flooding is disrupting indigenous ways of life and floods bring assaults on community health, like diarrhea, skin disease, and malnutrition. Community activities that contribute to development such as education and healthcare are also paralyzed by these impacts. Adaptation funding will be essential for her community to survive and to avoid disruptive displacement.

Still, perhaps the most compelling political reason for American taxpayers to invest in climate change adaptation in the developing world is the national security implications of the effects of climate change. A report issued this week by the Center for American Progress and the Alliance for Climate Protection explains why the United States must have a global climate investment strategy, despite adverse economic and political conditions domestically. Adaptation funding will “reduce risks of climate-related national security threats, including from severe floods or droughts in Pakistan and the Middle East” and strengthen our relationships with developing country recipients, including strategically important partners like India, Indonesia, and Brazil, write the authors. Finally, by managing displacement, migration, and violent conflict driven by the effects of climate change, such as water scarcity, climate change adaptation can help bolster international security and stability.

The establishment of a climate green fund here in Cancun is essential for an equitable and balanced international climate deal. A fund is first and foremost the moral imperative of developed countries, known as the Annex-I parties under the UNFCCC, who are historically responsible for greenhouse gas emissions. However, developed countries need not rely on the moral argument to convince policymakers and taxpayers that climate adaptation for the poorest and most vulnerable countries and people is a good investment.

Within the UN process itself, a robust, well-run, equitable green fund would help rebuild the trust lost between developed and developing countries at Copenhagen last year. In Gore’s words, Oxfam is “cautiously optimistic that we can get an agreement here in Cancun that rebuilds trust between rich and poor countries.”

Alex Stark is a program assistant at the Friends Committee on National Legislation, working on the Peaceful Prevention of Deadly Conflict Program. She is attending the Cancun negotiations as part of the Adopt a Negotiator team.

Sources: Alliance for Climate Protection, British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Center for American Progress, Global Campaign for Climate, Mozambique Ministry of Planning and Finance, Oxfam, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Women’s Environment and Development Organization.

Photo Credit: “Will you back a climate fund?,” courtesy of flickr user Oxfam International. -

What’s Good for Women Is Good for the Planet

›Ammi, my mother-in-law, was 16 years old when her marriage was arranged. Before she was 18, she had borne her first child, who died within the year, and by 30, she had given birth to six more. She had a fourth-grade education, and like other women in the new state of Pakistan, she knew little about contraceptive choices.

More than 50 years later, contraception still remains inaccessible for millions of women in Pakistan, such as Rani, the young woman who cleans Ammi’s Karachi home. Illiterate and married off to a cousin at age 15, Rani already has three children, and, like the majority of married Pakistani women who have never used modern contraception, will most likely have at least one more.Giving women the ability to determine whether and when to become pregnant is fundamental to the realization of their basic human rights. It is also a proven health and development strategy, substantially reducing maternal and infant mortality by allowing women to space their pregnancies. And now, for the first time, two studies offer compelling evidence that it has another benefit: What is good for women is also good for our planet.

These groundbreaking studies have rigorously quantified the effect on the environment of helping women and girls control their reproductive destinies. The studies – “The World Population Prospects and Unmet Need for Family Planning,” by the Futures Group, and, “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions,” by the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis – demonstrate that giving women and girls access to contraception offers a precious co-benefit: a substantial reduction in carbon emissions.

The logic is simple: When women have the power to plan their families, populations grow more slowly, as do greenhouse gas emissions. The cost of providing these needed family planning services worldwide is minimal compared with other development and emissions reductions strategies – roughly $3.7 billion per year.

More than 200 million women in the United States and developing countries are sexually active and do not want to become pregnant, yet are not using modern contraception. The results are staggering: One in four births worldwide is unplanned, leading to 42 million abortions each year (half of them clandestine) and 68,000 women’s deaths.

Moreover, the large number of women who become pregnant when they do not want to is a significant source of population growth. Read in tandem, the studies show that a reduction of 8-15 percent of essential carbon emissions can be obtained simply by providing modern contraception to all women who want it. This reduction would be equivalent to stopping all deforestation or increasing the world’s use of wind power 40-fold. Although this is just one piece of the emissions reduction puzzle, it is a substantial piece.

The world is now facing multi-layered challenges of economic distress, rising inequality, and environmental devastation caused by climate change. International climate negotiations have repeatedly stalled as powerful nations play the blame game and block progress. Meanwhile, a series of severe weather events has buffeted the earth from Moscow to Iowa to Pakistan, each one hitting women and children hardest. This is the reality that rich nations must reckon with – and commit to changing – today.

In my 14 years at the Global Fund for Women, I have observed the wave of change that comes from empowering women – what some call the “girl effect.” Making information, education, and contraception easily available offers us an affordable, no-regrets strategy that can be implemented now.

Meeting the need for family planning services is not a complex challenge. We know how to provide the commodities, services, and education that women and their families want. There are thousands of programs around the world with successful track records in every conceivable religious, cultural, and political setting.

Investing in family planning has already been proven as an essential strategy to ensure the health, safety, and development of societies. Now we know that it is also an effective way to safely steward Mother Earth through one of her most challenging crises.

Kavita N. Ramdas is chair of the Expert Working Group of the Aspen Institute’s Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health and senior adviser and former president and CEO of the Global Fund for Women.

Sources: Futures Group, National Center for Atmospheric Research and the International Institute for Applied Systems, Science, UNFPA, WHO.

Photo Credit: “Chaco: Madre pilagá,” courtesy of flickr user Ostrosky Photos, and Kavita Ramdas, courtesy of Global Fund for Women.

Showing posts from category Guest Contributor.