-

‘UK Royal Society: Call for Submissions’ “People and the Planet” Study To Examine Population, Environment, Development Links

›August 12, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffBy Marie Rumsby of the Royal Society’s In Verba blog.

In the years that followed the Iranian revolution, when Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile to Tehran and the country went to war against Iraq, the women of Iran were called upon to provide the next generation of soldiers. Following the war the country’s fertility rate fell from an average of over seven children per woman to around 1.7 children per woman – one of the fastest falls in fertility rates recorded over the last 25 years.

Iran is an interesting example but every country has its own story to tell when it comes to population levels and rates of change. The global population is rising and is set to hit 9 billion by 2050. And whilst fertility rates in Ethiopia are on the decline, its total population is projected to double from around 80 million today, to 160 million in 2050.

Earlier this month, the Royal Society announced it is undertaking a new study which will look at the role of global population in sustainable development. “People and the Planet” will investigate how population variables – such as fertility, mortality, ageing, urbanization, and migration – will be affected by economies, environments, societies, and cultures, over the next 40 years and beyond.

The group informing the study is chaired by Nobel Laureate Sir John Sulston FRS, and includes experts from a range of disciplines, from all over the world. With names on the group such as Professor Demissie Habte (President of the Ethiopian Academy of Sciences), Professor Alastair Fitter FRS (Professor Environmental Sciences, University of York) and Professor John Cleland FBA (Professor of Medical Demography, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine), there’s bound to be some lively discussions.

Linked to the announcement of the study, the Society held a PolicyLab with Fred Pearce, environmental journalist, and Jonathon Porritt, co-founder of Forum for the Future, to discuss the significance of population in sustainable development.

Both speakers have been campaigning against over-consumption for many years. Jonathon Porritt has been a keen advocate for fully funded, fully engaged voluntary family planning in every country in the world that wants it.

“In my opinion, that would allow us to stabilize global population at closer to 8 billion, rather than 9 billion. And if we did it seriously for forty years, that is an achievable goal.” Porritt thinks that stabilizing global population at 8 billion rather than 9 billion would save a large number of women’s lives, and suggests “you cannot ignore the gap between 8 billion and 9 billion if you are thinking seriously about climate change.”

Fred Pearce acknowledges that population matters, but stresses that it is consumption (and how we produce what we produce) that we need to focus on. He feels it is too convenient for us to focus on population.

According to Fred, the global average is now 2.6 children per woman – that’s getting close to the global replacement level of 2.3 children per woman.

“It is no longer human numbers that are the main threat……It’s the world’s consumption patterns that we need to fix, not its reproductive habits,” said Pearce.

The Society will be taking a long look at some of these issues, assessing the latest scientific evidence and uncertainty around population levels and rates of change. The “People and the Planet” study is due for publication in early 2012, ahead of the Rio+20 UN Earth Summit. The Society is currently seeking evidence to inform this study from a wide-range of stakeholders.

The deadline for submissions is October 1, 2010. For more information on submissions, please see the Royal Society’s full call for evidence announcement.

Image Credit: “In Verba” courtesy of the Royal Society. -

How Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Impact Economic Development

›“Investing in women and girls is the right thing to do,” says Mayra Buvinic, sector director of the World Bank’s gender and development group. “It is not only fair for gender equality, but it is smart economics.” But while it may be smart economics, many developing countries fail to address the underlying social causes that impact economic growth, such as poverty and gender inequality. Buvinic was joined by Dr. Nomonde Xundu, health attaché at the Embassy of South Africa in Washington, D.C., and Mary Ellen Stanton, senior maternal health advisor at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), at the sixth meeting of the Advancing Policy Dialogue on Maternal Health Series, which addressed the economic impact of maternal mortality and provided evidence for the need for increased investment in maternal health.

-

“There Is No Choice:” Climate, Health, Water, Food Security Must Be Integrated, Say Experts

›August 9, 2010 // By Russell SticklorBureaucratic stovepipes plague international development efforts, and aid for pressing environmental and human security concerns—such as climate change, food shortages, fresh water access, and global health threats—rarely matches the reality on the ground in the developing world, where such health and environmental problems are fundamentally interconnected.

Instead, development efforts in the field—whether spearheaded by multilaterals, bilaterals, or NGOs—are commonly devoted to single sectors: e.g., the prevention and treatment of a single disease; the implementation of irrigation infrastructure in a specific area; or the introduction of a new crop in a certain region. The reasons for such a narrow focus can come from multiple sources: finite resources, narrowly constructed funding streams, emphasis on simple and discrete indicators of success, and institutional and professional development penalties for those who conduct integrated work. But some experts argue that integrating problem-solving initiatives across categories would not only improve the efficacy of development efforts, but also better improve lives in target communities.

As part of the USAID Knowledge Management Center‘s 2010 Summer Seminar Series, a recent National Press Club panel on integration featured a frank discussion of both the opportunities and challenges inherent in breaking down barriers within and between development agencies. Panelists from the World Bank’s Environment Department, the White House Council on Environmental Quality, and the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Environment Change and Security Program weighed in on the prospects for cross-sectoral integration.

Addressing the impacts of a global problem like climate change “requires multilevel approaches,” and necessitates that we “think multisectorally along the lines of agriculture, water, transportation, energy, [and] security,” said Loren Labovitch of the White House Council on Environmental Quality. The four topics under discussion—climate change, food security, water, and health—are all Obama administration priorities, as reflected by dedicated programs and special initiatives. Finding ways to practically integrate these interrelated challenges (through efforts like the Feed the Future Initiative or the Global Health Initiative) is getting more attention from policy analysts and policymakers with each passing year.

Integration in Practice: Success Stories

While there may be an emerging willingness to discuss and even experiment with holistic programming, what does it actually look in practice? Panelist Geoff Dabelko, director of the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program, singled out integrated development programs in the Philippines, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Asia as examples.

Philippines: The PATH Foundation Philippines’ Integrated Population and Coastal Resource Management (IPOPCORM) initiative uses an integrated approach to address health and environmental concerns in coastal communities. Their “basket of services” includes establishing a locally managed protected marine sanctuary to allow local fish stocks to recover, promoting alternative economic livelihoods outside of the fishing industry, and improving access to local health services and commodities, said Dabelko. To date, IPOPCORM has yielded several notable improvements, among them reduced program costs and improved health and environmental outcomes as compared to side-by-side single sector interventions. A forthcoming peer-reviewed article will appear in Environmental Conservation, and will detail the controlled comparison study of the IPOPCORM project.

Democratic Republic of Congo: Mercy Corps has also successfully pursued cross-sectoral programming as part of a larger effort to be more holistic in its humanitarian and development responses. In war-torn eastern DRC, Mercy Corps brought practitioners with expertise in natural resource management into the fold of what has historically been an emergency relief mission. In particular, the Mercy Corps mission has fused humanitarian assistance with longer-term development efforts such as enhanced environmental stewardship. For example, promoting the use of fuel-efficient cookstoves eases pressure on local forest resources by lowering the need for firewood, and improves respiratory health by lowering air pollution. The project scaled up the effort through resources from further integration, with carbon credits from avoided emissions being sold through a local broker to the European cap and trade market. These resources in turn helped finance more cook stoves, which now total 20,000 for this project.

“The lesson is we have no excuse for not doing this anywhere in the world and saying some place is too unstable,” Dabelko said. “If we can do it [integrated projects] in eastern DRC, we should be able to do it anywhere.”

Asia: Tackling programmatic integration starts with better understanding the interconnections between environmental and health challenges. Dabelko cited a recent effort of the environment and natural resources team within USAID’s Asia Bureau as an example of breaking out of narrow bureaucratic stovepipes.

USAID staff recognized that a wide set of climate, energy, economic, governance, and conflict issues affected their core biodiversity and water portfolios, even if they did not have the time, expertise, or resources to investigate those issues in detail. Trends that appeared to be in the periphery were not viewed as peripheral to planning and designing programs for long-term success.

Working with the Woodrow Wilson Center, the USAID Asia Regional Bureau engaged experts on a diverse set of topics normally considered outside their portfolios. The resulting workshop series and report led to a deeper understanding of the possible impacts of increased Himalayan glacier melt and Chinese hydropower plans on food security and biodiversity programs in the lower reaches of the Mekong River. Bringing analysis from these topically and geographically remote areas into local-level development planning is a process that will require a similar willingness to go outside the typical bounds of one’s brief.

More Integration Ahead?

These case studies provide a glimpse of what integrated programming can look like on the ground. Still, significant hurdles remain standing in the way of regular and effective integration. Cross-sectoral programming demands that old problems be addressed in innovative and perhaps unfamiliar ways, requiring the addition of new capacity in development organizations and better coordination within and between agencies. That can be a complicated process, noted Dabelko, since efforts to pursue greater programming integration can be “hamstrung by earmarks and line items.”

Integration can also prove tricky because it requires a greater willingness to accept multiple indicators of success unfolding over different time frames—health gains may occur quickly, for example, while progress on environmental conservation may unfold less speedily. This means existing programs might need to be reshaped and reoriented to accommodate these divergent time frames, which could prove somewhat difficult. “Integration can be a challenge, both from a programming perspective and from an organizational perspective,” acknowledged moderator Tegan Blaine, climate change advisor for USAID’s Africa Bureau.

Further, the temptation remains strong among appropriators and implementers alike to maintain control over authority and resources in their traditional portfolios. Getting long-time practitioners in particular issue areas to willingly cede some of their turf in the pursuit of greater integration has historically been the “real world” that stands in the way of such integrated work.

But, as shown by the standing-room-only crowd at the seminar, momentum is slowly starting to build in pursuit of breaking down old programming walls and finding new approaches to addressing emerging challenges in human and environmental security.

“There is no choice” but to fuse development agendas with climate change adaptation efforts, asserted Warren Evans, director of the World Bank’s Environment Department. “It can’t be a parallel process anymore.”

Photo Credit: “2010 Summer Seminar Series – July 15th Panel Discussion on Food Security, Climate Change, Water and Health,” used courtesy of USAID and the National Press Club. -

Reform Aid to Pakistan’s Health Sector, Says Former Wilson Center Scholar

›August 5, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffExcerpt from op-ed by Samia Altaf and Anjum Altaf in Dawn:

WE must state at the outset that we have been wary of, if not actually opposed to, the prospect of further economic assistance to Pakistan because of the callous misuse and abuse of aid that has marked the past across all elected and non-elected regimes.

We are convinced that such aid, driven by political imperatives and deliberately blind to the well-recognised holes in the system, has been a disservice to the Pakistani people by destroying all incentives for self-reliance, good governance and accountability to either the ultimate donors or recipients.

Even without the holes in the system the kind of aid flows being proposed are likely to prove problematic. Over half a century ago, Jane Jacobs, in a brilliant chapter (Gradual and Cataclysmic Money) in a brilliant book (The Death and Life of Great American Cities), showed convincingly how ‘cataclysmic’ money (money that arrives in huge amounts in short periods of time) is a surefire way of destroying all possibilities of improvement. What is needed, she argued, is ‘gradual’ money in the control of the residents themselves. While Jacobs was writing in the context of aid to impoverished communities within the US, she concluded with a remarkably prescient concern: “I hope we disburse foreign aid abroad more intelligently than we disburse it at home.”

Continue reading on Dawn.

For more on U.S. aid to Pakistan, see New Security Beat‘s coverage of the recent U.S.-Pakistani Strategic Dialogue.

Photo Credit: A U.S. Army Soldier with 32nd Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division, hands out medical supplies to Pakistani refugees outside an International Committee of the Red Crescent aid station in Afghanistan’s Kunar province, October 23, 2009. Courtesy of flickr user isafmedia. -

‘Restrepo’: Inside Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley

›August 2, 2010 // By Marie HokensonRestrepo, the riveting new documentary film from Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger, follows a platoon of U.S. soldiers deployed in the dangerous Korengal Valley of Afghanistan. As a cadet at West Point majoring in human geography, I was fascinated to watch the ways the soldiers confronted and adapted to the challenges posed by the local culture of the remote Afghan community surrounding their outpost.

West Point’s human geography program delves into the relationships between facets of society and geography that may also have potentially significant security implications. In the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. troops fight insurgents in difficult environments – from heavily urbanized cities to extremely remote valleys – while interacting with civilian populations with radically different languages and cultures.

Restrepo: Culture in Action and Under Fire

At the remote outpost Restrepo, named in memory of a medic killed in action, the platoon receives daily fire from insurgents as they seek to improve security enough to allow the construction of a road through the valley.

At a weekly shura, the company commander explains the benefits of the road to the village elders, yet they are either unconvinced or uninterested. This frustrating meeting reveals a cultural disconnect: the Americans see the road as the way to win Afghan “hearts and minds” by facilitating progress and bringing more revenue to the community, but the Afghans are suspicious of the Americans’ motives and promises, and not convinced of the benefits.

Another culture clash arises when a cow is caught in the outpost’s concertina wire. The soldiers kill the seriously injured cow, but this proves to be a continual source of tension in negotiations between the soldiers and the locals. Killing the cow was illegal, say the Afghan elders, who seek financial compensation that the Army is not willing to provide. Perhaps better understanding of regional culture could have prevented this relatively minor incident from souring relations.

On the other hand, by attending the traditional shura gatherings with village elders, the U.S. soldiers are showing their respect for Afghan culture while facilitating negotiations and, potentially, the sharing of useful intelligence.

Although not shown in the film, the U.S. military also demonstrates its understanding of Afghan culture through the growing use of female soldiers to reach out to Afghan women. As many women in Afghanistan are not allowed to be seen by unrelated men, female soldiers are tasked with searching houses and Afghan women, as well as assessing their need for aid and gathering intelligence from them.

West Point: Culture in Theory and Practice

Dealing with the problems faced by today’s soldiers, like those in Restrepo, requires understanding the current conflict landscape and its security implications. Understanding the influence of religion, language, development, and people on the world’s geography is vital to mapping the combat terrain.

Human geography instruction at West Point provides cadets with more perceptive views of other countries and the complex problems they face. Military geography analyzes urban and natural environments, as well as related interactions, such as the impact of population dynamics and nature resources on military operations. Land-use planning and management addresses conflicts over land use and environmental strategies. Other opportunities, such as study-abroad programs and interactions with foreign cadets, increase our exposure to other cultures and geographies.

Through my study of human geography, I have gained a much greater understanding of the people and countries where I travel and work today – and where I will go in the future as a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army.

Marie Hokenson is a cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point and an intern with the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program.

Photo Credit: “Mutual support,” courtesy of flickr user The U.S. Army. -

Drug Barons, Poachers, Ranchers, Oh My! Guatemala’s Forests Under Siege

›July 29, 2010 // By Kayly OberLast week, the New York Times ran an article about the many threats converging on Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve. “There’s traffickers, cattle ranchers, loggers, poachers and looters,” Richard D. Hansen, an American archaeologist, told NYT. “All the bad guys are lined up to destroy the reserve. You can’t imagine the devastation that is happening.”

Eric Olson, senior associate of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center, agrees that drug trafficking is a major problem in the Petén, a region of northern Guatemala that lies within the Biosphere. “Petén’s isolation has made it possible for the biodiversity of the area to survive and thrive during periods of great social turmoil, especially in the 1980s,” Olson told the New Security Beat. “However, the isolation also makes it an ideal place for drug traffickers to move their illegal product northward.”

According to NYT, peasant squatters in search of farmland constitute an additional threat because they “often become pawns of the drug lords,” and, in some instances, “function as an advance guard for the drug dealers, preventing the authorities from entering, warning of intrusions, and clearing land that the drug gangs ultimately take over.”

Plus, the situation seems poised to worsen. According to a UNESCO report, Petén’s population has surged from 25,000 during the 1970s to upwards of 500,000 today. This growth, coupled with an attendant rise in subsistence farming, has had significant environmental impacts across the region.

Population Growth in Protected Areas

“Population has a huge impact on Guatemala’s ecological diversity,” David López-Carr, an associate professor in the University of California-Santa Barbara’s Geography Department, wrote in an e-mail to the New Security Beat. Most striking, according to López-Carr, are total fertility rates in rural areas, which remain “over 5 and much higher still – higher than 6 – in the most remote rural areas where ecological diversity is highest.”

Despite the fact that most migrants move to Guatemala City, smaller cities, or the United States, López-Carr wrote that the “tiny fraction (probably under 5%) that move to remote rural areas have a major impact on biodiversity and forest conversion.” López-Carr pointed out that “in core conservation areas of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, in-migration has swelled the population in some regions by nearly 10% annually during the past two decades.”

At a 2008 meeting at the Woodrow Wilson Center, professors Justin Brashares and George Wittemyer said three factors drive population growth near protected areas in Africa and Latin America: 1) more money for parks (as measured by protected-area funds from the Global Environment Facility); 2) more park employees; and 3) more deforestation on the edges of protected areas.

To avoid population pitfalls, Guatemala’s President Alvaro Colom should take this research into account before putting his “Cuatro Balam” eco-tourism plan into action. The initiative—named for the four main figures in the Mayan creation myth—seeks to divide the reserve into an archaeological park in the north and an agricultural zone in the south, while setting up a Maya studies center for scholars and installing an $8 million electric mini-train to shuttle tourists through the reserve.

The Perils of “Pristine Conservation”

While President Colom’s plan is certainly ambitious, communities in Petén are cautious. They see Cuatro Balam as a continuation of earlier government-funded projects, where “pristine conservation” – oft-touted by large conservation organizations – prohibited human interaction with the forests and limited socioeconomic opportunities for local populations.

Liza Grandia, an anthropology professor at Clark University who has lived and worked in the Peten region, points out in Conservation and Society that “primary” or “pristine” forests flagged as biological hotspots by these conservation organizations are likely remnants of ancient Mayan agroforestry. However, Mayan descendents are not allowed to live within nor manage these areas.

Instead, stewardship of many federal parks is delegated to large conservation outfits or the government. But Rosa Maria Chan, director of ProPeten, a community-based environmental organization, wrote in an e-mail to the New Security Beat that “the environment is not always the government’s priority,” adding that “development” normally signifies large infrastructure projects, instead of smaller-scale ideas that would better address human development.

The Benefits of Community-Based Conservation

One successful local project is the Association of the Forest Community of Péten (ACOFOP), a community-based association made up of 23 indigenous and farming organizations. Under ACOFOP’s direction, uncontrolled settlement in the biosphere reserve has been stopped, communities have ceased the conventional slash-and-burn practices, and forest fires have virtually ceased in community-managed areas. ACOFOP’s projects have also created jobs in local communities, where the beneficiaries re-invest their earnings into collective infrastructure.

In the mid-1990s/early 2000s, ProPeten’s Remedios I and II programs, funded mainly by USAID, used radio soap operas and mobile theaters to educate residents about conservation, reproductive health, nutrition, and sustainable agriculture. Underlying these programs’ success was an unprecedented survey that gathered data on the rapidly changing population-environment dynamics in this frontier region.

Grandia, who served as head of ProPeten’s board of directors from 2003-2005, writes in 2004 Wilson Center article that “the integrated DHS [Demographic and Health Survey] has been a critical part of developing…programs linking health and population with the environment,” which lowered Petén’s total fertility rate from 6.8 to 5.8 children per woman in just four years. Plans are underway to include a similar environmental module in the next DHS survey.

Although the fate of Guatemala’s forests is subject to many outside forces, from the government’s development plans to the cartel’s smuggling operations, small-scale, community-based programs may have the best shot at transforming the drivers of deforestation into sustainable, economic development opportunities.

Photo Credit: “Keel-billed Toucan at Tikal National Park, Guatemala,” courtesy of flickr user jerryoldenettel. -

Talk Versus Action

‘Dialogue Television’ on Rebuilding Haiti

›Watch below or on MHz Worldview

In the aftermath of Haiti’s 7.0 earthquake, the world turned its attention to the impoverished and devastated island nation (including the New Security Beat, which covered some its demographic problems). Reporters, relief workers, and volunteers from around the globe rushed to provide coverage and aide. Western leaders announced bold blueprints for building a “new Haiti.” Six months later, only a tiny portion of pledged funds have been delivered, over one million Haitians remain homeless, and much of the country’s infrastructure remains in ruins. This week on dialogue, host John Milewski speaks with Donna Leinwand of USA Today and Sheri Fink, Public Policy Scholar at the Wilson Center, on their experiences working and reporting in Haiti after the devastation. Scheduled for broadcast starting July 21st, 2010 on MHz Worldview channel.

Donna Leinwand is a reporter for the nation’s top-selling newspaper, USA Today. She’s been with the paper since 2000, covering legal issues, major crimes, the Justice Department, terrorism, and natural disasters. She is also a past president of the National Press Club. Sheri Fink is a senior fellow with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, a staff reporter for Pro Publica, and is a public policy scholar at the Wilson Center. She was awarded a 2010 Pulitzer Prize for her investigative piece on doctors at a hospital cut off by Hurricane Katrina flood waters.

Note: A QuickTime plug-in may be required to launch the video. -

Wilson Center’s Michael Kugelman Finds the Real Culprit in Pakistan’s Water Shortage

›July 28, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffExcerpt from Dawn:

ON Jan 15, 2006, the Karachi Port Trust (KPT) inaugurated its new fountain – the Rs320m lighted harbour structure that spews seawater hundreds of feet into the air.

Also on this day – as on most others in Karachi – several million gallons of the city’s water supply were lost to leakage, some hundred million gallons of raw sewage oozed into the sea, and scores of Karachiites failed to secure clean water.

Over the next few years, the fountain jet would produce a powerful and relentless stream of water high above Karachi. Meanwhile, down below, tens of thousands of the city’s masses would die from unsafe water.

After several fountain parts were stolen in 2008, the KPT quickly made the necessary repairs and re-launched what it deems “an extravaganza of light and water”.

In an era of rampant resource shortages, boasting about such extravagance demonstrates questionable judgment. So, too, does the willingness to lavish millions of rupees on a giant water fountain, and then to repair it fast and furiously – while across Karachi and the nation as a whole, drinking water and sanitation projects are heavily underfunded and water infrastructure stagnates in disrepair.

Continue reading on Dawn.

For more on Pakistan’s water crisis, see the Wilson Center report, “Running on Empty.”

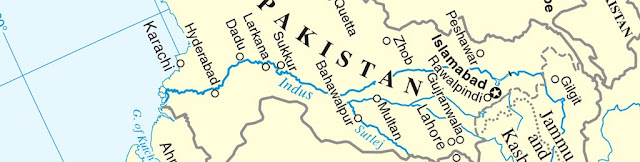

Photo Credit: Adapted from UN map of South Asia, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Showing posts from category development.