-

Chad Briggs: Dealing With Risk and Uncertainty in Climate-Security Issues

›July 21, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffWe must do more than simply take our current understanding of climate-change risk and extrapolate it into the future, asserted Chad Briggs of the Berlin-based Adelphi Research in a video interview with the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program.

-

Demographics, Depleted Resources, and Al Qaeda Inflame Tensions in Yemen

›July 21, 2010 // By Schuyler NullA second spectacular Al Qaeda attack on Yemeni government security buildings in less than a month is a worrisome sign that the terrorist group may be trying to take advantage of a country splitting at the seams. U.S. officials are concerned that Yemen, like neighboring Somalia, may become a failed state due to a myriad of challenges, including a separatist movement in the south, tensions over government corruption charges, competition for dwindling natural resources, and one of the fastest growing populations in the world.

Wells Running Dry

Water shortages have become commonplace in Yemen. Last year, the Sunday Times reported that Yemen could become the first modern state to run out of water, “providing a taste of the conflict and mass movement of populations that may spread across the world if population growth outstrips natural resources.”

Earlier this year, government forces came to blows with locals over a disputed water well license in the south. Twenty homes were damaged and two people were killed during the resulting eight day stand-off, according to Reuters.

The heavily populated highlands, home to the capital city of Sanaa, face particularly staggering scarcity. Wells serving the two million people in the capital must now stretch 2,600 – 3,200 feet below the surface to reach an aquifer and many have simply dried up, according to reports.

Yemeni Water and Environment Minister Abdul-Rahman al-Iryani told a Reuters reporter that the country’s burgeoning water crisis is “almost inevitable because of the geography and climate of Yemen, coupled with uncontrolled population growth and very low capacity for managing resources.”

Nineteen of Yemen’s 21 aquifers are being drained faster than they can recover, due to diesel subsidies that encourage excessive pumping, loose government enforcement of existing drilling laws, and growing population demand. Qat farmers in particular represent an excessive portion of water consumption; growing the popular narcotic accounts for 37 percent of agricultural water consumption. Meanwhile, according to a study by the World Food Programme this year, 32.1 percent of the population is food insecure and the country has become reliant on imported wheat.

Yemen’s other wells – the oil variety – have long been the country’s sole source of significant income. According to ASPO, oil has historically represented 70-75 percent of the government’s revenue. But recent exploration efforts have failed to uncover significant additions to Yemen’s reserves, and as a result oil exports have declined 56 percent since 2001. The steep decline has pushed Yemeni authorities to look to other natural resources, such as rare minerals and natural gas, but the infrastructure to support such projects will take significant time and money to develop.

The Fastest Growing Population in the Middle East

Despite the country’s limited resources, Yemen’s population of 22.8 million people is growing faster than any other country in the Middle East. According to projections from the Population Reference Bureau, by 2050, Yemen’s burgeoning population is expected to rival that of Spain.

Fully 45 percent of the current population is under the age of 15 – a troubling ratio that is expected to grow in the near future. The charts from the U.S. Census Bureau embedded below illustrate the dramatic growth of the country’s youth bulge from 1995 through 2030.

A poor record on women’s rights and a highly rural, traditional society contribute to these rapid growth scenarios. According to Population Action International’s Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, only 41 percent of Yemeni women are literate and their total fertility rate is well over the global average. A recent survey from Social Watch ranking education, economic, and political empowerment rated Yemen last in the world in gender equity. Yemeni scholar Sultana Al-Jeham pointed out during her Wilson Center presentation, “Yemeni Women: Challenges and Little Hope,” that there is only one woman in a national parliament of 301 members and that ambitious political women routinely face systematic marginalization.

A contributing factor is that 70 percent of Yemen’s population live outside of cities – far more than any other country in the region – making access to education and healthcare difficult, especially in the large swaths of land not controlled by the government.

External migration from war-torn east Africa adds to Yemen’s demographic strains. According to IRIN, approximately 700,000 Somali refugees currently reside in country, and that number may grow as the situation in Somalia continues to escalate. Within Yemen’s own borders, another 320,000 internally displaced people have fled conflict-ridden areas, further disrupting the country’s internal dynamics.

Corruption and Rebellion

Competition over resources, perceived corruption, and Al Qaeda activity have put considerable pressure on the Saleh regime in Sanaa. The government faces serious dissidence in both the north and the south, and the Los Angeles Times reports that talk of rebellion is both widespread and loud:Much of southern and eastern Yemen are almost entirely beyond the central government’s control. Many Yemeni soldiers say they won’t wear their uniforms outside the southern port city of Aden for fear of being killed. In recent months, officials have been attacked after trying to raise the Yemeni flag over government offices in the south.

USAID rates Yemen’s effective governance amongst the lowest in the world (below the 25th percentile), reflecting Sanaa’s poor control and high levels of corruption. Some reports claim that up to a third of Yemen’s 100,000-man army is made up of “ghost soldiers” who do not actually exist but whose commanders collect their salaries and equipment to sell on the open market.

The West and Al Qaeda

In testimony before Congress earlier this year, Assistant Secretary of State Jeffrey Feltman called on the Yemeni government to take a comprehensive approach to “address the security, political, and economic challenges that it faces,” including its natural resource and demographic challenges.

The Yemeni government is poised to receive $150 million in bilateral military assistance from the United States. But some experts are critical of that approach: Dr. Mustafa Alani of the Dubai-based Gulf Research Center told UN Dispatch that, “you are not going to solve the terrorist problem in Yemen by killing terrorists,” calling instead for investing in economic development.

USAID has budgeted $67 million for development assistance, economic support, and training programs in Yemen for FY 2010 and has requested $106 million for FY 2011 (although about a third is designated for foreign military financing).

While Yemen’s Al Qaeda presence continues to captivate Western governments, it is the country’s other problems – resource scarcity, corruption, and demographic issues – that make it vulnerable to begin with and arguably represent the greater threat to its long-term stability. The United States and other developed countries should address these cascading problems in constructive ways, before the country devolves into a more dangerous state like Somalia or Afghanistan. In keeping with the tenets of the Obama administration’s National Security Strategy, an exercise in American soft power in Yemen might pay great dividends in hard power gains.

Sources: Association for the Study of Peak Oil – USA, Central Intelligence Agency, Congressional Research Service, Guardian, IRIN, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Population Action International, Population Reference Bureau, ReliefWeb, Reuters, Social Watch, Sunday Times, U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of State, UN Dispatch, USA Today, USAID, World Food Programme.

Photo Credit: “Yemen pol 2002” via Wikimedia Commons courtesy of the U.S. Federal Government and “Yemen youth bulge animation” arranged by Schuyler Null using images courtesy of the U.S. Census Bureau’s International Data Base. -

In Kampala, African Leaders Discuss Maternal Health While Attacks Renew Concern over Somalia

›July 19, 2010 // By Schuyler NullLeaders from 49 African countries are meeting today in Kampala, Uganda, at the start of a scheduled week-long African Union (AU) summit on maternal and child health. Uganda is a fitting location, as it faces some of the toughest health and demographic challenges in Africa, including a very young and rapidly growing population and poor maternal health services. However, with the memory of last week’s twin bomb blasts still fresh, peace and security issues will surely be on the agenda as well.

Somalia’s lead insurgency group, Al Shabab, took responsibility for the attacks in Kampala, which killed more than 70 people. Al Shabab’s first prominent cross-border attack is only the latest sign that Somalia’s issues – which also include a very young and rapidly growing population – are starting to spill over its borders. For more on Somalia’s deepening crisis and its effects on the East African region, see New Security Beat’s recent analysis: “As Somalia Sinks, Neighbors Face a Fight to Stay Afloat.”

Sources: AP, Washington Post.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Ugandan African Union contingent in Mogadishu, Nov. 25, 2007” courtesy of flickr user david axe. -

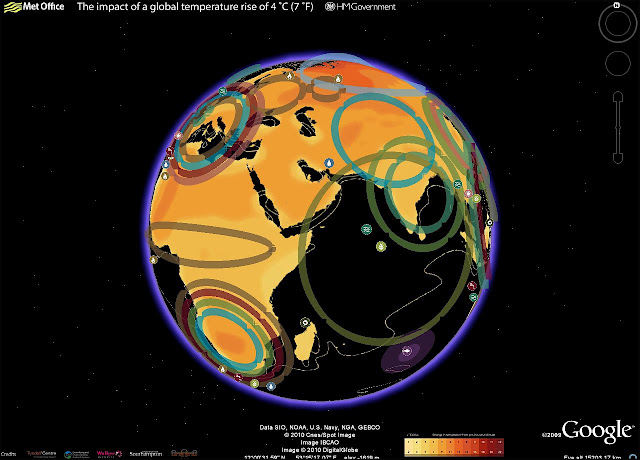

Rear Admiral Morisetti Launches the UK’s “4 Degree Map” on Google Earth

›Having had such success with the original “4 Degree Map” that the United Kingdom launched last October, my colleagues in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office have been working on a Google Earth version, which users can now download from the Foreign Office website.

This interactive map shows some of the possible impacts of a global temperature rise of 4 degrees Celsius (7° F). It underlines why the UK government and other countries believe we must keep global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial times; beyond that, the impacts will be increasingly disruptive to our global prosperity and security.

In my role as the UK’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy I have spoken to many colleagues in the international defense and security community about the threat climate change poses to our security. We need to understand how the impacts, as described in this map, will interact with other drivers of instability and global trends. Once we have this understanding we can then plan what needs to be done to mitigate the risks.

The map includes videos from the contributing scientists, who are led by the Met Office Hadley Centre. For example, if you click on the impact icon showing an increase in extreme weather events in the Gulf of Mexico region, up pops a video clip of the contributing scientist Dr Joanne Camp, talking about her research. It also includes examples of what the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and British Council are doing to increase people’s awareness of the risks climate change poses to our national security and prosperity, thus illustrating the FCO’s ongoing work on climate change and the low-carbon transition.

Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti is the United Kingdom’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy. -

DRC’s Conflict Minerals: Can U.S. Law Impact the Violence?

›July 13, 2010 // By Schuyler NullApple CEO Steve Jobs, in a personal email posted by Wired, recently tried to explain to a concerned iPhone customer the complexity of ensuring Apple’s devices do not use conflict minerals like those helping to fund the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. However much one might be tempted to pile on Apple at the moment, Mr. Jobs is on to something with regard to the conflict minerals trade – expressing outrage and raising awareness of the problem is one thing but actually implementing an effective solution is quite another.

As finely articulated in a number of recent articles about conflict minerals in the DRC (see the New York Times, Guardian, and Foreign Policy for example), the Congo is, and has been for some time, a failed state.

Although a ceasefire was signed in 2003, fighting has continued in the far east of the country around North and South Kivu provinces, home to heavy deposits of tin, gold, coltan, and other minerals. The remote area is very diverse ethnically and has seen clashing between government troops and various militias from the Congo itself as well as encroachments by its neighbors Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi. Referred to as “the Third World War” by many, there are by some accounts 23 different armed groups involved in the fighting, and accusations of massacres, rampant human rights abuses, extortion, and pillaging are common. According to the UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, “there is almost total impunity for rape in the Congo,” and a survey by the International Rescue Committee puts the estimated dead from preventable diseases, malnutrition, and conflict in the area at over five million over the past decade (or 45,000 deaths a month).

At a recent event in Washington, DC on this terrible conflict (see Natural Security for an excellent summary), DRC Ambassador Faida Mitifu expressed her hope to the audience and panel (including U.S. Under Secretary of State Robert Hormats) that they would not limit themselves to “just talking.” Hosts John Pendergast and Andrew Sullivan of the NGO Enough Project hope to address the demand side of Congo’s mineral trade by pushing Congress to pass the Conflict Minerals Trade Act, which would require U.S. companies to face independent audits to certify their products are conflict mineral-free.

But Laura Seay, of Texas in Africa and the Christian Science Monitor, is dubious of this proposal, pointing out that:Without the basic tools of public order in place and functioning as instruments of the public good in the DRC, the provisions of this bill are likely to work about as well as the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme does in weak states that lack functioning governmental institutions – which is to say, not at all.

The Kimberely Process (KP) is a certification scheme that is supposed to stem the flow of “blood diamonds” that support corrupt regimes and fuel human rights abuses. But the KP’s governing body has recently reached a crisis of action over whether or not to punish Zimbabwe for alleged abuses, with one diamond magnate even claiming, according to IRIN, that “corrupt governments have turned the KP on its head – instead of eliminating human rights violations, the KP is legitimizing them.”

The problem with international transparency schemes like the Kimberely Process, the proposed Conflict Minerals Act, or even EITI, is that at the very least, a functioning government – if not a beneficent one – is needed to enforce regulations at the source. In the DRC’s case, not only does the government have little to no authority over the affected areas, but the mining militias are smuggling their loot, on foot in some cases, directly into neighboring countries anyway. By the time they reach U.S. companies (if ever – Americans are not the only consumers in the world), conflict minerals have passed hands so many times that proving their provenance is next to impossible.

Then there is the question of whether or not cutting off the militias, rogue military officials, and government forces from conflict mineral monies would even end violence in the region in the first place. Certainly many armed groups gain a great deal from their illegal mining activities (as do some locals), but is it the root cause of their discontent? In the best case scenario where mining revenues are actually decreased, would that really convince the remnants of the Hutu Interahamwe, fleeing retribution from the now majority-Tutsi Rwandan government, to suddenly put down their weapons? How about the Mai Mai, who are fighting the Hutu incursion into their homeland?

I for one find that hard to believe. Stopping the conflict mineral trade from afar is very difficult, if not impossible, and even if we could end the trade, it would not necessarily stop the suffering. Illegal mining does play a large part in supporting rebel groups, but to address the human security problems that have so horrified the world, international attention ought to first be turned toward improving governance mechanisms in the Congo and rethinking the troubled UN peacekeeping mission (how about more involvement out of U.S. AFRICOM too?). The failure of the current UN mission is well documented, but withdrawing the largest peacekeeping force in the world in the face of continued violence, including the recent death of Congo’s most famous human rights activist under suspicious circumstances, seems more likely to cause harm than good.

Would passing the Conflict Minerals Act make Apple consumers feel better? Perhaps. But that’s not the point. Environmental security measures that prevent the DRC’s tremendous mineral wealth from being used to fund conflict can only make an impact if the government has some measure of accountable control over the area. To make a real difference in east Congo, human security must first be addressed directly and forcefully.

Sources: BBC, Christian Science Monitor, Daily Beast, Human Rights Watch, IPS News, IRIN News, International Rescue Committee, Enough Project, Foreign Policy, GlobalSecurity.org, Globe and Mail, New York Times, Share the World’s Resources, Southern Times, Times Online, UN, Wired.

Image Credit: “Minerals and Forests of the DRC” from ECSP Report 12, courtesy of Philippe Rekacewicz, Le Monde diplomatique, Paris, and Environment and Security Institute, The Hague, January 2003. -

U.S. Navy Task Force on Implications of Climate Change

›What about climate change will impact us? That’s the question the Navy’s Task Force Climate Change is trying to answer. Rear Admiral David Titley explains the task force’s objectives in this interview by the American Geophysical Union (AGU) at their recent “Climate Change and National Security” event on the Hill.

The task force is part of the military’s recent efforts to try to better understand what climate change will mean for the armed forces, from rising sea levels and ocean acidification to changing precipitation patterns. In the interview, Admiral Titley points out that for the Navy in particular, it is important to understand and anticipate what changes may occur since so many affect the maritime environment.

The Navy’s biggest near-term concern is the Arctic, where Admiral Titley says they expect to face significant periods of almost completely open ocean during the next two to three decades. “That has huge implications,” says Titley, “since as we all know the Arctic is in fact an ocean and we are the United States Navy. So that will be an ocean that we will be called upon to be present in that right now we’re not.”

Longer term, the admiral points to resource scarcity and access issues and sea level rise (potentially 1-2 meters) as the most important contributing factors to instability, particularly in places like Asia, where even small changes can have huge impacts on the stability of certain countries. The sum of these parts plus population growth, an intersection we examine here at The New Security Beat, is something that deserves more attention, according to Titley. “The combination of climate, water, demographics, natural resources – the interplay of all those – I think needs to be looked at,” he says.

Check out the AGU site for more information, including an interview with Jeffrey Mazo – whose book Climate Conflict we recently reviewed – discussing climate change winners and losers and the developing world (hint: the developing world are the losers).

Sources: American Geophysical Union, New York Times.

Video Credit: “What does Climate Change mean for the US Navy?” courtesy of YouTube user AGUvideos. -

Backdraft: The Conflict Potential of Climate Mitigation and Adaptation

›The European Union’s biofuel goal for 2020 “is a good example of setting a target…without really thinking through [the] secondary, third, or fourth order consequences,” said Alexander Carius, co-founder and managing director of Adelphi Research and Adelphi Consult. While the 2007-2008 global food crisis demonstrated that the growth of crops for fuels has “tremendous effects” in the developing world, analysis of these threats are underdeveloped and are not incorporated into climate change policies, he said. [Video Below]

-

New Security Challenges in Obama’s Grand Strategy

›June 4, 2010 // By Schuyler NullPresident Obama’s National Security Strategy (NSS), released last week, reinforces a commitment to the whole of government approach to defense, and highlights the diffuse challenges facing the United States, including international terrorism, globalization, and economic upheaval.

Following the lead of the Quadrennial Defense Review released earlier this year, the NSS for the first time since the Clinton years prominently features non-traditional security concerns such as climate change, population growth, food security, and resource management:Climate change and pandemic disease threaten the security of regions and the health and safety of the American people. Failing states breed conflict and endanger regional and global security… The convergence of wealth and living standards among developed and emerging economies holds out the promise of more balanced global growth, but dramatic inequality persists within and among nations. Profound cultural and demographic tensions, rising demand for resources, and rapid urbanization could reshape single countries and entire regions.

By acknowledging the myriad causes of instability along with more “hard” security issues such as insurgency and nuclear weapons, Obama’s national security strategy takes into account the “soft” problems facing critical yet troubled states – such as Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and Somalia – which include demographic imbalances, food insecurity, and environmental degradation.

Not surprisingly, Afghanistan in particular is highlighted as an area where soft power could strengthen American security interests. According to the strategy, agricultural development and a commitment to women’s rights “can make an immediate and enduring impact in the lives of the Afghan people” and will help lead to a “strong, stable, and prosperous Afghanistan.”

The unique demographic landscape of the Middle East, which outside of Africa has the fastest growing populations in the world, is also given intentional consideration. “We have a strategic interest in ensuring that the social and economic needs and political rights of people in this region, who represent one of the world’s youngest populations, are met,” the strategy states.

Some critics of that strategy warn that the term “national security” may grow to encompass so much it becomes meaningless. But others argue the administration’s thinking is simply a more nuanced approach that acknowledges the complexity of today’s security challenges.

In a speech on the strategy, Secretary of State Clinton said that one of the administration’s goals was “to begin to make the case that defense, diplomacy, and development were not separate entities either in substance or process, but that indeed they had to be viewed as part of an integrated whole and that the whole of government then had to be enlisted in their pursuit.”

Compare this approach to President Bush’s 2006 National Security Strategy, which began with the simple statement, “America is at war” and focused very directly on terrorism, democracy building, and unilateralism.

Other comparisons are also instructive. The Bush NSS mentions “food” only once (in connection with the administration’s “Initiative to End Hunger in Africa”) and does not mention population, demography, agriculture, or climate change at all. In contrast, the 2010 NSS mentions food nine times, population and demography eight times, agriculture three times, and climate change 23 times – even more than “intelligence,” which is mentioned only 18 times.

For demographers, development specialists, and environmental conflict specialists, the inclusion of “new security” challenges in the National Security Strategy, which had been largely ignored during the Bush era, is a boon – an encouraging sign that soft power may return to prominence in American foreign policy.

The forthcoming first-ever Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review by the State Department will help flesh out the strategic framework laid out by the NSS. It is expected to provide more concrete policy for integrating defense, diplomacy, and development. Current on-the-ground examples like USDA embedding in Afghanistan, stepped-up development aid to Pakistan, and the roll-out of the administration’s food security initiative, “Feed the Future,” are encouraging signs that the NSS may already be more than just rhetoric.

Update: The Bush 91′ and 92’ NSS also included environmental considerations, in part due to the influence of then Director of Central Intelligence, Robert Gates.

Sources: Center for Global Development, CNAS, Los Angeles Times, State Department, USAID, White House, World Politics Review.

Photo Credit: “Human, Food, and Demographic Security” collage by Schuyler Null from “Children stop tending to the crop to watch the patrol” courtesy of flickr user isafmedia, “Combing Wheat” courtesy of flickr user AfghanistanMatters, and “Old Town Sanaa – Yemen 49” courtesy of flickr user Richard Messenger.

Showing posts from category security.