Showing posts from category environment.

-

Annie Murphy, International Reporting Project

Mozambique Coal Mine Brings Jobs, Concerns

›May 31, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Annie Murphy appeared on the International Reporting Project and NPR (follow the links for the accompanying audio track as well). Murphy appeared with three other IRP fellows at the Wilson Center on April 28 to talk about their experiences reporting abroad.

As developing countries grow, their need for raw materials grows, too.

This is the case for Brazil, a country that has much in common with the nation of Mozambique: Both have a mix of African and Portuguese influences; both are rich in natural resources; and both fought long and hard to throw off European colonialism.

Today, however, a Brazilian coal mine in Mozambique has some wondering what the energy demands of growing economies like Brazil really mean for African countries like Mozambique.

This coal mine in northwestern Mozambique is owned by the Brazilian company Vale — it’s a gaping, dark gray pit in the middle of a green, windswept savannah. Still under construction, it currently employees about 7,500 people.

Jose Manuel Guilengue, 23, a machine operator, says that he and a friend traveled 1,000 miles from the capital to get there, where they were both hired. That was a year ago. He now makes around $400 a month — which is more than four times the average salary in Mozambique.

According to the general manager overseeing construction, Osvaldo Adachi, this mine will produce about 11 million tons of coal each year, for at least three decades.

Continue reading and listen to the audio at the International Reporting Project.

Annie Murphy reported this story during a fellowship with the International Reporting Project (IRP). To hear more about Murphy and the IRP program, see the event summary for “Reporting on Global Health: A Conversation With the International Reporting Project Fellows.”

Photo Credit: Adapted from Mozambique, courtesy of flickr user F H Mira. -

Elizabeth C. Economy, Council on Foreign Relations

The Truth About the Three Gorges Dam

›May 26, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Elizabeth C. Economy, appeared on the Council on Foreign Relations’ Asia Unbound blog.

It has only taken 90 years, but China’s leaders have finally admitted that the Three Gorges Dam is a disaster. With Wen Jiabao at the helm, the State Council noted last week that there were “urgent problems” concerning the relocation effort, the environment and disaster prevention that would now require an infusion of US$23 billion on top of the $45 billion spent already.

Despite high-level support for the project since Sun Yat-sen first proposed it in 1919, the dam has had serious critics within China all along. One of China’s earliest and most renowned environmental activists, Dai Qing, published the book Yangtze! Yangtze! in 1989, which explored the engineering and social costs of the proposed dam. The book was a hit among Tiananmen Square protestors, and Dai spent a year in prison for her truth-telling. In 1992, when the dam came up for a vote in the National People’s Congress, an unprecedented one-third of the delegates voted against the plan.

Once the construction began in 1994, the problems mounted. The forced relocation of 1.4 million Chinese was plagued with corruption; former Premier Zhu Rongji accused the construction companies of shoddy engineering, and little of the pollution control measures that were planned were actually taken. Water pollution skyrocketed in the reservoir. As Chinese officials acknowledged a few years back, “The Three Gorges Dam project has caused an array of ecological ills, including more frequent landslides and pollution, and if preventive measures are not taken, there could be an environmental catastrophe.”

It would be easy to argue that the State Council’s admission was too little too late. However, the new transparency matters for at least two reasons. First, it plays into the hands of environmentalists who have been arguing against Beijing’s aggressive plans for additional large-scale hydropower plants. Premier Wen, who has tried to slow the approval process for dams over the past several years, now has a bit more ammunition. Second, any acknowledgement by the Party that mistakes have been made is an important step toward the public’s right to question future policies. Let’s hope that more such transparency is on the way.

Elizabeth C. Economy is the C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and director for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Construction of the Three Gorges Dam,” courtesy of flickr user Harald Groven. -

Environmental Action Plans in Darfur: Improving Resilience, Reducing Vulnerability

›Many villagers in Baaba, a community of 600 in South Darfur, remember a shady forest of mango and guava trees that provided food and a valuable income for the villagers and a pleasant picnic spot for people in Nyala, the nearby state capital. Over the last decade, that forest has degraded into eroded brush dotted by the occasional baobab – a transformation that is unfortunately a familiar sight throughout Darfur.

Most of Baaba’s trees have become firewood and charcoal for the people living in nearby internally displaced persons (IDP) camps. Baaba’s residents, who themselves returned from the camps to try to rebuild their lives at home, struggle to coax enough food from the soil, which has largely eroded away following deforestation. Afraid to venture any further than necessary from home for fear of violence and banditry in the countryside, they farm and graze the same land year after year without fallow periods – further depleting the soil and driving yields ever lower.

Baaba is like hundreds of Darfuri villages, which face a brutal mix of insecurity and environmental decline that leaves them one poor harvest away from being forced into the IDP camps. Baaba, however, is also a pilot participant in a new approach – the Community Environmental Action Plan – that aims to rehabilitate the local environment, enable people to sustainably manage natural resources, and ultimately to make communities more prosperous and resilient.

Most of Darfur has always been marginal land where farming and herding provide a meager livelihood and natural resources are few. Even before war broke out in 2003, soaring population growth (total population has quintupled since the 1970s) was putting intolerable pressure on the land, water, and trees of Darfur. The conflict in Darfur has since heavily disrupted traditional methods for sharing and maintaining natural resources, leading to environmental devastation. The worsening effects of climate change – though hard to separate from local environmental depletion – are also beginning to disrupt weather patterns and farming. The disheartening result is that even where fighting has subsided and displaced persons return home, they often find that the land no longer sustains them.

Traditional humanitarian aid and infrastructure projects are ill-suited to help, since persistent insecurity deprives humanitarian actors of access to communities for weeks or months at a time. Environmental decline didn’t start the humanitarian crisis in Darfur, but it threatens to prolong it and put a sustainable peace out of reach.

Community Environmental Action Plans

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), mandated to work on IDP and return issues in Darfur, aimed to address these challenges with Community Environmental Action Plans (CEAPs) in three pilot villages. CEAPs build comprehensive local capacity, enabling communities to manage natural resources sustainably and address environmental problems themselves without relying on outside support. The ultimate goal is to build the resilience and adaptive capacity of vulnerable communities. IOM worked with Baaba and two other villages to implement CEAPs, in partnership with the Swiss-based environmental NGO ProAct, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the government of South Darfur, and Darfuri environmental organizations. The project, funded by the Government of Japan, ran from early 2009 until mid-2010.

The CEAP process trains communities to understand the connections between a healthy ecosystem and a prosperous community and to promote livelihoods by rehabilitating the environment. Each participating village formed a CEAP governance committee, which was then trained to understand the environment as a single integrated system and to see how damaging one resource like trees can devastate other ecosystem services – such as pollination, groundwater retention, and soil fertility – that enable and promote human livelihoods. The communities then identified essential needs, including reforestation, water harvesting, and improved sanitation, and worked with IOM to develop appropriate responses. These activities were all implemented by the villages themselves, with technical and material support from IOM and its partners.

Building Local Capacity

The communities built low-tech but highly productive tree nurseries, producing and planting over 200,000 seedlings to restore damaged land and provide a sustainable wood supply. Local women learned how to make highly fuel-efficient stoves using locally available materials, cutting their need for firewood and allowing them to sell stoves in the nearby Nyala market. Farmers received extensive training in sustainable agriculture techniques, including water harvesting, composting, agro-forestry, and intercropping (mixing complementary plant species together in the same fields). Volunteers were trained in effective hygiene practices and built latrines for each household. Water committees were trained to repair and maintain the villages’ indispensable but fragile water hand pumps, ensuring a more reliable source of drinking water. Each of these activities was governed by a community committee, including women and youth, trained to manage the projects for the benefit of the entire community and continue the work after the project’s end.

Farmers received extensive training in sustainable agriculture techniques, including water harvesting, composting, agro-forestry, and intercropping (mixing complementary plant species together in the same fields). Volunteers were trained in effective hygiene practices and built latrines for each household. Water committees were trained to repair and maintain the villages’ indispensable but fragile water hand pumps, ensuring a more reliable source of drinking water. Each of these activities was governed by a community committee, including women and youth, trained to manage the projects for the benefit of the entire community and continue the work after the project’s end.

Through this approach, all three villages significantly boosted their livelihoods and agricultural productivity while becoming less dependent on the unsustainable exploitation of their fragile environment. The CEAP approach benefits greatly from focusing on capacity-building and local implementation, which fosters a strong sense of community ownership that persists after the project ends. Equally important, CEAPs attempt to address most or all of a community’s environmental issues simultaneously, reducing the risk that neglected environmental problems – particularly agricultural failure – will critically destabilize and displace a community in the future.

A Replicable Model

CEAPs aren’t a panacea, particularly in the conflict-prone areas where they are most needed. Insecurity, particularly a series of abductions of humanitarian workers from several organizations in 2010, cut off IOM’s access to the communities late in the project. Though the core activities were completed by working through local partners with more reliable access, the security situation left few opportunities for follow-up activities. Longer-term threats, particularly unrestrained population growth – which requires a comprehensive approach that includes addressing unmet need for family planning services – could undo much of the good that CEAPs accomplish.

Though insecurity prevented IOM from continuing the project, other organizations including UNEP are implementing and refining the CEAP approach elsewhere in Darfur and other regions in sub-Saharan Africa. As climate changes intensifies and the potential for related conflicts looms, the CEAP approach should be considered as a powerful and flexible tool to rehabilitate the environment and strengthen vulnerable communities.

Paul Rushton is a consultant for the International Organization for Migration, Sudan, and worked as a Programme Officer managing the CEAP projects in South Darfur from 2009 to 2010.

Sources: International Organization for Migration, UN.

Photo Credit: Camels graze in a destroyed and degraded village in Western Darfur, courtesy of UNEP; and pictures from CEAP sites in Southern Darfur, courtesy of Paul Rushton. -

Meeting Half the World’s Fuel Demands Without Affecting Farmland Joan Melcher, ChinaDialogue

Biofuels: The Grassroots Solution

›May 24, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Joan Melcher, appeared on ChinaDialogue.

The cultivation of biofuels – fuels derived from animal or plant matter – on marginal lands could meet up to half of the world’s current fuel consumption needs without affecting food crops or pastureland, environmental engineering researchers from America’s University of Illinois have concluded following a three-year study. The findings, according to lead author Ximing Cai, have significant implications not only for the production of biofuels but also the environmental quality of degraded lands.The study, the final report of which was published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology late last year, comes at a time of increasing global interest in biomass. The International Energy Agency predicts that biomass energy’s share of global energy supply will treble by 2050, to 30 percent. In March, the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development called on national governments to take a “more sophisticated” approach to the energy source, putting it at the heart of energy strategies and ramping up investment in new technologies and research programs.

The University of Illinois project used cutting-edge land-use data collection methods to try to determine the potential for second-generation biofuels and perennial grasses, which do not compete with food crops and can be grown with less fertilizer and pesticide than conventional biofuels. They are considered to be an alternative to corn ethanol – a “first generation” biofuel – which has been criticized for the high amount of energy required to grow and harvest it, its intensive irrigation needs and the fact that corn used for biofuel now accounts for about 40 percent of the United States entire corn crop.

A critical concept of the study was that it only considered marginal land, defined as abandoned or degraded or of low quality for agricultural uses, Cai, who is civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Illinois in the mid-western United States, told ChinaDialogue.

The team considered cultivation of three crops: switchgrass, miscanthus, and a class of perennial grasses referred to as low-impact high-diversity (LIHD).

Continue reading on ChinaDialogue.

Sources: Sources: International Energy Agency, Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, Reuters, University of Illinois.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Biofuels,” courtesy jurvetson. -

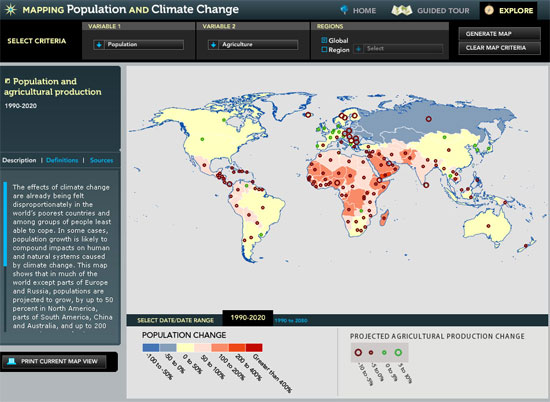

Mapping Population and Climate Change

›Climate change, population growth, unmet family planning needs, water scarcity, and changes in agricultural production are among the global challenges confronting governments and ordinary citizens in the 21st century. With the interactive feature “Mapping Population and Climate Change” from Population Action International, users can generate maps using a variety of variables to see how these challenges relate over time.

Users can choose between variables such as water scarcity or stress, temperature change, soil moisture, population, agriculture, need for family planning, and resilience. Global or regional views are available, as well as different data ranges: contemporary, short-term projections (to the year 2035), and long-term projections (2090).

In the example featured above, the variables of population change and agricultural production change were chosen for the time period 1990-2020. Unfortunately, no country-specific data is given, though descriptions in the side-bar offer some helpful explanations of the selected trends.

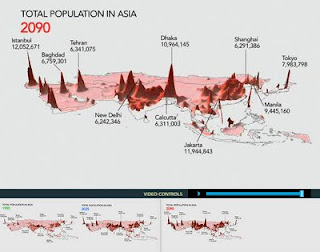

In addition, users can view three-dimensional maps of population growth in Africa and Asia for the years 1990, 2035, and 2090. These maps visually demonstrate the projected dramatic increases in population of these regions by the end of the century. According to the latest UN estimates, most of the world’s population growth will come from Africa and Asia due to persistently high fertility rates.

Image Credit: Population Action International. -

Rosemarie Calvert, Center for a Better Life

Winning Hearts and Minds: An Interview with Chief Naval Officer Admiral Gary Roughead

›May 23, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Rosemarie Calvert, appeared in the Center for a Better Life’s livebetter magazine.

Few people understand “smart” power as well as Chief Naval Officer (CNO) Admiral Gary Roughead. To this ingenious, adept leader of the world’s largest and most powerful navy, it’s not just about military strategy or political science; it’s about heart. It’s about the measure of a man with regard to honor, courage and commitment. And, it’s about appreciation and respect for the natural world. As one of the U.S. Defense Department’s most powerful decision-makers, Roughead has helped mold a new breed of sailor who understands that preventing war is just as important as winning war – that creating partners is more important than creating opponents. Add mission mandates such as humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and environmental stewardship, and it’s clear why Roughead and his brand of smart power are having a profound impact on international peace, national security, and natural security.

Engendering Environmental Advocacy

“You don’t live on the ocean and not love it. My appreciation for the environment came from a very early age – from just loving to be on the water. It’s something that’s had a very strong impact on me,” explains Roughead, who grew up in North Africa where his father worked in the oil business. He and his family lived along an uninhabited area of coastline where his father’s company built a power plant and refinery to process and transport Libya’s huge oil field finds to offshore tankers.

“We were the first people to move there; I was still in grammar school. The beauty in being the first was that the coastline was absolutely pristine. Even before school, I would get up and go skin diving. There were beautiful reefs, and fish were everywhere. The vegetation was just incredible. The company built an offshore loading area a few miles off the beach with 36-inch pipes pumping crude oil out to where these big supertankers would come in. Back then, there wasn’t a high regard for the environment, so when storms would kick-up and ships got underway in a hurry, they would just cast them off and all that oil would go into the ocean.

“Fast forward about five years, and the last time I went skin diving I didn’t see a living thing. The vegetation was dead. At that time I was visiting my folks on summer leave from the Naval Academy. There were periods when I would skin dive and then surface after being down about 35-40 feet, and my lungs would be ready to burst. I’d look up, having moved from my original location, and see this massive oil slick. And, I’d go, ‘Oh gosh…no!’ But, you didn’t have any choice. I would come home and actually have to clean the oil off with kerosene because it was caked on me.

“I saw and experienced environmental devastation, and it had an effect on me. Being at sea all the time – I love going to sea and seeing everything about it – drove me to the views I have. I really do think there’s compatibility between the Navy and the environment. We have things we must accomplish, but we can do them cleanly and responsibly. That’s what we’ve tried to demonstrate to those who have different views – that there has to be compatibility between the two.”

Continue reading on the Center for a Better Life.

Rosemarie Calvert is the publisher and editorial director of livebetter magazine and director of the Center for a Better Life.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “USS Nitze underway with ships from U.S. Navy, Coast Guard and foreign navies,” courtesy of flickr user Official U.S. Navy Imagery. -

Climate Change, Development, and the Law of Mother Earth

Bolivia: A Return to Pachamama?

›May 20, 2011 // By Christina DaggettIn Bolivia, environment-related contradictions abound: shrinking glaciers threaten the water supply of the booming capital city, La Paz, while unusually heavy rainfall triggers deadly landslides. The government is seeking to develop a strategic reserve of metals that could make Bolivia the “Saudi Arabia of lithium,” while politicians promote legal rights for “Mother Earth” and an end to capitalism.

This year has been particularly turbulent. In La Paz, landslides destroyed at least 400 homes and left 5,000 homeless. While the rain has been overwhelming at times, it has also been unreliable – an effect of the alternating climate phenomena La Niña and El Niño, experts say, which have grown more frequent in recent years and cause great variability in weather patterns. Bolivia has endured nine major droughts and 25 floods in the past three decades, a challenge for any country but particularly so for one of the poorest, least developed, and fastest growing (with a total fertility rate over three) in Latin America.

Environmental Justice or Radicalism?

Environmentalism has become a major force in national politics in part as a response to the climatic challenges faced by Bolivia. A new law seeks to grant the environment the same legal rights as citizens, including the right to clean air and water and the right to be free of pollution. (Voters in Ecuador approved a similar measure in 2008.) The law is seen as a return of respect to Pachamama, a much revered spiritual entity (akin to Mother Earth) for Bolivia’s indigenous population, who account for around 62 percent of the total population.

Though groundbreaking in its scope, the new law may prove difficult to enforce, given its lack of precedent and the lucrative business interests at stake (oil, gas, and mineral extraction accounted for 70 percent of Bolivia’s exports in 2010).

On the global stage, President Morales has issued perhaps the most aggressive calls yet for industrial countries to do more about climate change and compensate those countries that are already experiencing the effects. Bolivia refused to sign both the Copenhagen and Cancun climate agreements on grounds that the agreements were too weak. In Cancun, Morales gave a blistering speech:We have two paths: Either capitalism dies or Mother Earth dies. Either capitalism lives or Mother Earth lives. Of course, brothers and sisters, we are here for life, for humanity and for the rights of Mother Earth. Long live the rights of Mother Earth! Death to capitalism!

Bolivia’s stance has alienated potential allies: In 2010, the United States denied Bolivia climate aid funds worth $3 million because of its failure to sign the Copenhagen Accord.

Going… Going… Gone

Bolivia’s Chacaltaya glacier – estimated to be 18,000 years old – is today only a small patch of ice, the victim of rising temperatures from climate change, scientists say. Glaciologists suggest that temperatures have been steadily rising in Bolivia for the past 60 years and will continue to rise perhaps a further 3.5-4˚C over the next century – a change that would turn much of the country into desert.

Other Andean glaciers face a similar fate, according to the World Bank, which estimates that the loss of these glaciers threatens the water supply of some 30 million people and La Paz in particular, which, some experts say, could become one of the world’s first capitals to run out of water. The populations of La Paz and neighboring El Alto have been steadily growing – from less than 900,000 in 1950 to more than 2 million in 2011 – as more and more Bolivians are moving from the countryside to the city, putting pressure on an already dwindling water supply.

If the water scarcity situation continues to worsen, residents of the La Paz metropolitan area may migrate to other areas of the country, most likely eastward toward Bolivia’s largest and most prosperous city, Santa Cruz. Such migration, however, has the potential to inflame existing tensions between the western (indigenous) and eastern (mestizo) portions of the country.

Rising Prices, Rising Tension

The temperature is not the only thing on the rise in Bolivia; the price of food, too, is increasing. According to the World Food Program, since 2010, the price of pinto beans has risen 179 percent; flour, 44 percent; and rice, 33 percent. Shortages of sugar and other basic foodstuffs have been reported as well, leading to protests.

In early February, the BBC reported President Evo Morales was forced to abandon his plans to give a public speech after a group of protestors started throwing dynamite. A week later, nation-wide demonstrations paralyzed several cities, according to AFP, closing schools and disrupting services.

The Saudi Arabia of Lithium?

One way out for Bolivia’s economic woes might be its still nascent mineral extraction sector. Bolivia possesses an estimated 50 percent of the world’s lithium deposits (nine million tons, according to the U.S. Geological Survey), most of which is locked beneath the world’s largest salt flat, Salar de Uyuni. The size of these reserves has prompted some to dub Bolivia a potential “Saudi Arabia of lithium” – a title, it should be noted, that has also been bestowed upon Chile and Afghanistan.

Demand for lithium, which is used most notably in cell phones and electric car batteries, is expected to dramatically increase in the next 10 years as countries seek to lower their dependence on fossil fuels. Yet, some analysts have wondered if Bolivia’s lithium is needed, given the quality and current level of production of lithium from neighboring Chile and Argentina.

Others have questioned whether Bolivia has the necessary infrastructure to industrialize the extraction process or the ability to get its product to market, though Bolivia recently signed an agreement with neighboring Peru for port access. In an extensive report for The New Yorker, Lawrence Wright writes that “before Bolivia can hope to exploit a twenty-first century fuel, it must first develop the rudiments of a twentieth-century economy.” To this end, the Bolivian government last year announced a partnership with Iran to develop its lithium reserves – a surprising move, given Morales’ historical disdain for foreign investment.

Nexus of Climate, Security, Culture, and Development

The Uyuni salt flats are both a potent economic opportunity and one of the country’s most unspoiled natural wonders. How will Bolivia – a country of natural bounty and unique indigenous tradition – balance the need for development with its stated commitment to environmental principles?

Large-scale extraction may be worth the environmental cost, a La Paz economist told The Daily Mail: “We are one of the poorest countries on Earth with appalling life-expectancy rates. This is no time to be hard-headed. Without development our people will suffer. Getting bogged down in principles and politics doesn’t put food in people’s mouths.”

“The process that we are faced with internally is a difficult one. It’s no cup of tea. There are sectors and players at odds in this more environmentalist vision,” said Carlos Fuentes, a Bolivian government official, to The Latin American News Dispatch.

Sources: American University, BBC News, Bloomberg, Change.org, Christian Science Monitor, The Daily Mail, Democracy Now, Green Change, The Guardian, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia, IPS News, Latin America News Dispatch, MercoPress, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Population Reference Bureau, PreventionWeb, Reliefweb, Reuters, SAGE, Tierramerica, USAID, U.S. Geological Survey, UNICEF, Upsidedownworld, Wired UK, The World Bank, Yahoo, Yes! Magazine.

Photo credit: “la paz,” courtesy of flickr user timsnell and “Isla Incahuasi – Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia,” courtesy of flickr user kk+. -

Southern Africa, China, and “Sustainable Access”

The Mineral Security of the United States

›In a report titled “Elements of Security: Mitigating the Risks of U.S. Dependence on Critical Minerals,” author Christine Parthemore from the Center for a New American Security writes, “Growing global demand coupled with the mineral requirements necessary for both managing military supply chains and transitioning to a clean energy future will require not only clearer understanding, but also pragmatic and realistic solutions.” Minerals and rare earth elements such as lithium, gallium, and rhenium are critical elements for many defense technologies (e.g. jet engines, satellites, missiles, etc.) and alternative energy sources (batteries and wind turbines). Parthemore argues that U.S. policy should focus on preventing suppliers from exerting undue leverage (as China did in 2010), mitigating fiscal risk and cost overruns, reducing disruption vulnerability, and ensuring the United States is able to meet its growth goals in clean energy and other high-tech fields. In a report from the U.S. Air War College, author Stephen Burgess writes of the potential for conflict over competition for “strategic minerals” in five southern African states: South Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Namibia. The report, titled “Sustainability of Strategic Minerals in Southern Africa and Potential Conflicts and Partnerships,” states that growing industrial countries like China will compete, potentially aggressively, with the United States for sustainable access to elements such as chromium, manganese, cobalt, uranium, and platinum group metals. Burgess recommends that the United States become more engaged in southern Africa by providing development assistance to mining communities and developing strategic partnerships.

In a report from the U.S. Air War College, author Stephen Burgess writes of the potential for conflict over competition for “strategic minerals” in five southern African states: South Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Namibia. The report, titled “Sustainability of Strategic Minerals in Southern Africa and Potential Conflicts and Partnerships,” states that growing industrial countries like China will compete, potentially aggressively, with the United States for sustainable access to elements such as chromium, manganese, cobalt, uranium, and platinum group metals. Burgess recommends that the United States become more engaged in southern Africa by providing development assistance to mining communities and developing strategic partnerships.