Showing posts from category environment.

-

Consumption and Global Growth: How Much Does Population Contribute to Carbon Emissions?

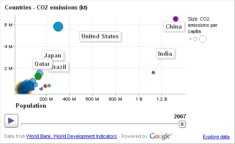

›July 6, 2011 // By Schuyler Null When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

In Prosperity Without Growth, first published by the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission and later by EarthScan as a book, economist Tim Jackson writes that it is “delusional” to rely on capitalism to transition to a “sustainable economy.” Because a capitalist economy is so reliant on consumption and constant growth, he concludes that it is not possible for it to limit greenhouse gas emissions to only 450 parts per million by 2050.

It’s worth noting that the UN has updated its population projections since Jackson’s original article. The medium variant projection for average annual population growth between now and 2050 is now about 0.75 percent (up from 0.70). The high variant projection bumps that growth rate up to 1.08 percent and the low down to 0.40 percent.

Either way, though population may play a major role in the development of certain regions, it plays a much smaller role in global CO2 emissions. In a fairly exhaustive post, Andrew Pendleton from Political Climate breaks down the math of Jackson’s most interesting conclusions and questions, including the role of population. He writes that the larger question is what will happen with consumption levels and technological advances:The argument goes like this. Growth (or decline) in emissions depend by definition on the product of three things: population growth (numbers of people), growth in income per person ($/person), and on the carbon intensity of economic activity (kgCO2/$). This last measure depends crucially on technology, and shows how far growth has been “decoupled” from carbon emissions. If population growth and economic growth are both positive, then carbon intensity must shrink at a faster rate than the other two if we are to slash emissions sufficiently.

Pendleton also brings up the prickly question of global inequity and how that impacts Jackson’s long-term assumptions:

Jackson calculates that to reach the 450 ppm stabilization target, carbon emissions would have to fall from today’s levels at an average rate of 4.9 percent a year every year to 2050. So overall, carbon intensity has to fall enough to get emissions down by that amount and offset population and income growth. Between now and 2050, population is expected to grow at an average of 0.7 percent and Jackson first considers an extrapolation of the rate of global economic growth since 1990 – 1.4 percent a year – into the future. Thus, to reach the target, carbon intensity will have to fall at an average rate of 4.9 + 0.7 + 1.4 = 7.0 percent a year every year between now and 2050. This is about 10 times the historic rate since 1990.

Pause at this stage, and take note that if there were no further economic growth, carbon intensity would still have to fall at a rate of 4.9 + 0.7 = 5.6 percent, or about eight times the rate over the last 20 years. To his credit, Jackson acknowledges this – as he puts it, decoupling is vital, with or without growth. Decoupling will require both huge innovation and investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon energy technologies. One question, to which we’ll return later, is whether and how you can get this if there is no economic growth.But Jackson doesn’t stop there. He goes on to point out that taking historical economic growth as a basis for the future means you accept a very unequal world. If we are serious about fairness, and poor countries catching up with rich countries, then the challenge is much, much bigger. In a scenario where all countries enjoy an income comparable with the European Union average by 2050 (taking into account 2.0 percent annual growth in that average between now and 2050 as well), then the numbers for the required rate of decoupling look like this: 4.9 percent a year cut in carbon emissions + 0.7 percent a year to offset population growth + 5.6 percent a year to offset economic growth = 11.2 percent per year, or about 15 times the historical rate.

To further complicate how population figures into all this, Brian O’Neill’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences article, “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions,” shows that urbanization and aging trends will have differential – and potentially offsetting – impacts on carbon emissions. Aging, particularly in industrialized countries, will reduce carbon emissions by up to 20 percent in the long term. On the other hand, urbanization, particularly in developing countries, could increase emissions by 25 percent.

What do you think? Is infinite growth possible? If so, how do you reconcile that with its effects on “spaceship Earth?” Do you rely on technology to improve efficiency? Do you call it a loss and hope the benefits of growth are worth it?

Sources: Political Climate, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Prosperity Without Growth (Jackson). -

Nepal to East Africa: Population, Health, and Environment Programs Compared

›“Practice, Harvest and Exchange: Exploring and Mapping the Global, Health, Environment (PHE) Network of Practice,” by the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Institute and the USAID-supported BALANCED Project, explores the successes and challenges of their global population, health, and environment (PHE) network (with a heavy presence in East Africa). In order to increase support of the nascent PHE approach, the network seeks to shorten the “collaborative distance” between “PHE champions,” so they can develop a stronger body of evidence for the links between population, health, and the environment. In their analysis, the authors write that the network has facilitated the development of independent, information-sharing relationships between “champions.” However, they also observed shortfalls in the network, such as its limited reach into less technologically advanced yet more biodiverse regions, its bias toward BALANCED meet-up event participants, and its exclusion of those experts unlikely to be included in published works. In “Linking Population, Health, and the Environment: An Overview of Integrated Programs and a Case Study in Nepal” from the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Sigrid Hahn, Natasha Anandaraja, and Leona D’Agnes provide both a broad survey of the structure and content of programs using the PHE method and an in-depth case study of a successful initiative in Nepal. Hahn et al. praise the Nepalese program for simultaneously addressing deforestation from fuel-wood harvesting, indoor air pollution from wood fires, acute respiratory infections related to smoke inhalation, as well as family planning in Nepal’s densely populated forest corridors. “The population, health, and environment approach can be an effective method for achieving sustainable development and meeting both conservation and health objectives,” the authors conclude. In particular, one benefit of cross-sectoral natural resource and development programs is the inclusion of men and adolescent boys typically overlooked by strictly family planning programs.

In “Linking Population, Health, and the Environment: An Overview of Integrated Programs and a Case Study in Nepal” from the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Sigrid Hahn, Natasha Anandaraja, and Leona D’Agnes provide both a broad survey of the structure and content of programs using the PHE method and an in-depth case study of a successful initiative in Nepal. Hahn et al. praise the Nepalese program for simultaneously addressing deforestation from fuel-wood harvesting, indoor air pollution from wood fires, acute respiratory infections related to smoke inhalation, as well as family planning in Nepal’s densely populated forest corridors. “The population, health, and environment approach can be an effective method for achieving sustainable development and meeting both conservation and health objectives,” the authors conclude. In particular, one benefit of cross-sectoral natural resource and development programs is the inclusion of men and adolescent boys typically overlooked by strictly family planning programs. -

Irene Kitzantides

In FOCUS Coffee and Community: Combining Agribusiness and Health in Rwanda

›June 29, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffDownload FOCUS Issue 22: “Coffee and Community: Combining Agribusiness and Health in Rwanda,” from the Wilson Center.

Rwanda, “the land of a thousand hills,” is also the land of 10 million people, making it the most densely populated country in Africa. Rwandans depend on ever-smaller plots of land for their food and livelihoods, leading to poverty, soil infertility, and food insecurity. Could Rwanda’s burgeoning specialty coffee industry hold the key to the country’s rebirth, reconciliation, and sustainable development?

In the latest issue of ESCP’s FOCUS series, author Irene Kitzantides describes the SPREAD Project’s integration of agribusiness development with community health care and education, including family planning. She outlines the project’s successes and challenges in its efforts to simultaneously improve both the lives and livelihoods of coffee farmers and their families. -

Scott Wallace, National Geographic

A Death Foretold

›June 23, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Scott Wallace, appeared on National Geographic News Watch.

Late last month the Brazilian Congress passed a bill that if it becomes law would ease restrictions on rain-forest clearing and make it easier than ever to mow down the Amazon. That same day, 800 miles north of the parliamentary chamber in Brasilia, assailants ambushed and killed a married couple whose opposition to environmental crimes had placed them in the crosshairs of those who most stand to gain from the new legislation.

It’s a nauseatingly familiar story. Over the past 20 years, there have been more than 1,200 murders related to land conflict in Brazil’s Amazon region. Most of the victims, like the married activists Zé Claudio Ribeiro and Maria do Espírito Santo, were defenders of the rain forest – people seeking sustainable alternatives to the plunder-for-profit schemes that characterize much of what passes for “development” in the Amazon.

The state of Pará – where Zé Claudio and Maria were ambushed on their motorbike as they crossed a rickety bridge – holds an especially notorious reputation for environmental destruction and organized violence. Pará is the bloodiest state in Brazil, accounting for nearly half of all land-related deaths in recent decades. It sprawls across an area larger than the states of Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico combined. Picture a tropical version of the Wild West, stripped of the romance, where loggers and ranchers muscle their way onto public land as though they own the place and impose a law of the jungle with their hired thugs. Those who have the nerve to protest soon find themselves the targets of escalating threats. If they persist, they find themselves staring down the gun barrels of those come to make good on the threats.

Continue reading on National Geographic.

Photo Credit: “Toras,” courtesy of flickr user c.alberto. -

Tim Siegenbeek van Heukelom, State-of-Affairs

Food Security in Kenya’s Yala Swamp

›June 21, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Tim Siegenbeek van Heukelom, appeared on State-of-Affairs.

In West Kenya on the Northeastern shore of Lake Victoria, the Yala swamp wetland is one of Kenya’s biodiversity hotspots. The Yala swamp also supports several communities that utilize the wetland’s natural resources to support their families and secure their livelihoods. Even more, many people recognize the swamp’s extraordinary potential as agricultural land to significantly boost Kenya’s food security. These are three widely diverse interests, which may seem to be difficult to reconcile. Yet, with proper management, sufficient investment and effective communication, a differentiated utilization of the Yala swamp can be realized through a system of multiple land use. This will be a difficult but certainly not unrealistic objective.

A Brief History

The most recent development of the Yala swamp was undertaken by Dominion Farms, a subsidiary of a privately held company from the United States investing in agricultural development. The reclamation and development of the swamp, however, is far from a new phenomenon.

The intention of the Kenyan government to transform parts of the Yala swamp into agricultural land for food production goes back as far as the early 1970s. Around that time, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands was consulted extensively by the Kenyan government for technical assistance on reclamation of the swamp and the feasibility of agricultural production.

Throughout the 1980s numerous reports were commissioned by the Kenyan Ministry for Energy and Regional Development and the Lake Basin Development Authority to the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Reports like the “Yala Integrated Development Plan” and the “Yala Swamp Reclamation and Development Project” focused in depth on the potential of the development of the swamp and made recommendations on practical matters, such as drainage and irrigation, soil analysis, agriculture, marketing, environmental aspects, employment opportunities, human settlement, management, and financial planning.

As a result, small-scale reclamation and development of the swamp land was undertaken throughout the 1980s and 1990s under the supervision of the Lake Basin Development Authority. The development of the swamp was partially successful, yet its scale was small and financial benefits were too marginal. Major investment was therefore required to extend the scale of the project.

Then, in 2003, an American investor expressed interest to make significant long-term investments into bringing parts of the swamp into agricultural production. Subsequently, a lease for 45 years was negotiated between Dominion Farms and the Siaya and Bondo County Councils to bring into agricultural production some 7,000 hectares of the Yala swamp. The whole Yala swamp wetland covers 17,500 hectares, which means that Dominion Farms is allowed to reclaim and develop roughly 40 percent of the swamp.

Protracted Conflict

Since the early days of the arrival of the foreign investor in 2004, there has been lingering tension and occasional flares of conflict between the communities surrounding the project site, third parties (i.e. government officials, politicians, NGOs, CBOs, environmentalists), and the investor.

The most commonly touted complaint is that Dominion Farms “grabbed” the communities’ land. While it is hard to trace back the exact procedures and individuals that were involved, there are clear contracts with the Siaya and Bondo County Councils that substantiate the transfer of land-use to Dominion Farms for a period of 45 years. Some claim, however, that the negotiation process for the lease was entrenched in bribery and corruption, yet no one has been able to show this author a single trace of evidence to substantiate these accusations. Similarly, there are complaints by local residents that they were never consulted in the negotiation process – where they should have been, as they rightly point out that the swamp is community trust land. However, the land is held in trust by the relevant county council for the community. The county council should therefore initiate consultations with the local communities and residents to get their approval to lease the land to third parties. So it appears that some of the resentment over the loss of parts of the swamp should not be directed at the foreign investor but rather target the local county council and their procedures.

Continue reading on State-of-Affairs. -

Watch: Richard Matthew at TEDxChange on Natural Resources, Conflict, and Environmental Peacemaking

›“It’s not surprising that about half the time, efforts to try to stabilize countries as they come out of war fail,” said Richard Matthew, associate professor at the University of California at Irvine and founding director of the Center for Unconventional Security Affairs, at a recent TEDxChange event. “Wars today are very destructive. They may not be as big as the wars of the last century, but they do a lot of damage.”

Matthew’s work focuses on the environmental dimensions of conflict and peacebuilding. Conflict can be spurred by competition over natural resources but it also contributes to further scarcity in many cases, creating a feedback loop. The natural resource aspect of conflict is particularly important in areas where livelihoods depend directly on access to land, water, and forests, he said.

In addition to discussing the benefits of including the environment in peacemaking efforts, Matthew also touched on the need for an increased proportion of national security spending to be spent on peace and development rather than defense. “It is in our interest to grow people out of the conditions that foster terrorism and extremism and infectious disease and crisis,” he said.

In particular, Matthew remains confident that an emerging group of leaders will find new and creative ways to support peacebuilding, natural resource management, and adaptation activities in the future: “Social entrepreneurs – people willing to combine their passion to make a better world with sound business tools – are developing truly innovative ways of taking daunting social problems and making them manageable.” -

Enhancing Public Engagement in Climate Change: The 2011 Climate Change Communicators of the Year

›

“Excellence in climate communication has to do with public engagement – communication that expands the portion of the public that is engaged in this issue and enhances their degree of engagement,” said Edward Maibach, director of the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University. “Enhancing Public Engagement in Climate Change: The 2011 Climate Change Communicators of the Year,” was held jointly by the Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) and George Mason University on June 8 to present awards for excellence in climate change communication by Naomi Oreskes and the Alliance for Climate Education.

-

Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

China’s Other Looming Choke Point: Food Production

›The original version of this article, by Keith Schneider, appeared on Circle of Blue.

Even along the middle reaches of the Yellow River, which irrigates 402,000 hectares (993,000 acres) of farmland north of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region’s provincial capital, there is still no mistaking the smell of dry earth and diesel fuel, the abiding scents of a desert province that is also among China’s most efficient grain producers.

Ningxia farmers have relied on the Yellow River since 221 BCE, when Qin Dynasty engineers clawed narrow trenches from the sand, introducing some of the first instances of irrigated agriculture on earth. Despite persistent droughts, in each of the last five years irrigation has made it possible for annual harvests to increase by an average of 100,000 metric tons.

The 2010 harvest of 3.5 million metric tons was nearly double what it was in 1990. The 3.9 million people who live and work on Ningxia’s 1.2 million farms, most no larger than three-quarters of a hectare (1.6 acres), produce the highest yields of rice and corn in the nine-province Yellow River Basin, according to central government crop statistics.

In sum, the farm productivity of this small northern China region – about the same size as West Virginia and located 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) to the west of the Bohai Sea – reflects the major shifts in geography and cultivation practices over the last generation that have made China both self-sufficient in food production and the largest grain grower in the world.

Yet Chinese farm officials here and academic authorities in Beijing are becoming increasingly concerned that China does not have enough water, good land, and energy to sustain its agricultural prowess. As Circle of Blue and the Woodrow Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum have reported in the Choke Point: China series, momentous competing trends – rising energy demand, accelerating modernization, and diminishing freshwater resources – are putting the country’s energy production and security at risk.

The very same trends also threaten China’s farm productivity. Last year, the national farm sector and the coal sector combined used 85 percent of the 599 billion cubic meters (158 trillion gallons) of water used in China.

Continue reading on Circle of Blue.

Keith Schneider is the senior editor of Circle of Blue and was a New York Times national correspondent for over a decade, where he continues to report as a special writer on energy, real estate, business, and technology.

Photo Credit: Used with permission, courtesy of J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue.