-

Urbanization, Climate Change, and Indigenous Populations: Finding USAID’s Comparative Advantage

›May 26, 2010 // By Kayly Ober “Part of the outflow of migrants from rural areas of many Latin American countries has settled in remote rural areas, pushing the agricultural frontier further into the forest,” writes David López-Carr in a recent article in Population & Environment, “The population, agriculture, and environment nexus in Latin America.” In a May 4 presentation at the LAC Economic Growth and Environment Strategic Planning Workshop in Panama City, Panama, he discussed how to integrate family planning and environmental services in rural Latin America.

“Part of the outflow of migrants from rural areas of many Latin American countries has settled in remote rural areas, pushing the agricultural frontier further into the forest,” writes David López-Carr in a recent article in Population & Environment, “The population, agriculture, and environment nexus in Latin America.” In a May 4 presentation at the LAC Economic Growth and Environment Strategic Planning Workshop in Panama City, Panama, he discussed how to integrate family planning and environmental services in rural Latin America.

Latin America is one of the most highly urbanized continents in the world, with an average of 75 percent of the population living in cities. However, “there are two Latin Americas,” said López-Carr at the workshop, which was sponsored by the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and Brazil Institute, as well as the U.S. Agency for International Development. Largely developed countries like Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay are close to 90 percent urbanized, while Guatemala, Ecuador, and Bolivia are about 50 percent. In less urbanized countries, rural-rural migrants in search of agricultural land remain a major driving force behind forest conversion, he said.

Between 1961 and 2001, Central America’s rural population increased by 59 percent, said Lopez-Carr. The increasing density of the rural population had a negative impact on forest reserves: a 15 percent increase in deforestation totaling some 13 million hectares.

“Rural areas of Latin America still have high fertility rates but (unlike much of rural Africa, for example) also have a high unmet demand for contraception, meaning that improved contraceptive availability would likely result in a rapid and cost-effective means to reduce population pressures in priority conservation areas,” he said. Additionally, remote rural areas with high population growth rates tend to be associated with indigenous populations located in close proximity to protected forests.

For example, in Guatemala, communities surrounding Sierra de Lacandon National Park have, since 1990, grown by 10 percent each year, with birthrates averaging eight children per woman. Larger communities and larger households have led to agricultural expansion, which infringes on the park and accelerates deforestation in one of the most biologically diverse biospheres in the world, said López-Carr.

Based on these demographic and environmental trends, López-Carr suggested USAID’s work in the region should focus on rural maternal and child health, and education – especially for girls. Not only does USAID already invest in such programs, but they only cost pennies per capita and could reduce the number of rural poor living in Latin American cities by tens of millions.

Given the strong links between population density and deforestation in Latin America, expanding access to family planning would also be a smart investment in forest conservation and climate mitigation, López-Carr concluded.

Source: Population Reference Bureau.

Photo Credit: Dave Hawxhurst, Woodrow Wilson Center. -

Look Beyond Islamabad To Solve Pakistan’s “Other” Threats

›After years of largely being ignored in Washington policy debates, Pakistan’s “other” threats – energy and water shortages, dismal education and healthcare systems, and rampant food insecurity – have finally moved to the front burner.

For several years, the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Asia Program has sought to bring these problems to the attention of the international donor community. Washington’s new determination to engage with Pakistan on its development challenges – as evidenced by President Obama’s signing of the Kerry-Lugar bill and USAID administrator Raj Shah’s comments on aid to Pakistan – are welcome, but long overdue.

The crux of the current debate on aid to Pakistan is how to maximize its effectiveness – that is, how to ensure that the aid gets to its intended recipients and is used for its intended purposes. Washington will not soon forget former Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf’s admission last year that $10 billion in American aid provided to fight the Taliban and al-Qaeda was instead diverted to strengthen Pakistani defenses against archrival India.

What Pakistani institutions will Washington use to channel its aid monies? In recent months, the U.S. government has considered both Pakistani NGOs and government agencies. It is now clear that Washington prefers to work with the latter, concluding that public institutions in Pakistan are better equipped to manage large infusions of capital and are more sustainable than those in civil society.

This conclusion is flawed. Simply putting all its aid eggs in the Pakistani government basket will not improve U.S. aid delivery to Pakistan, as Islamabad is seriously governance-challenged.

Granted, Islamabad is not hopelessly corrupt. It was not in the bottom 20 percent of Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index (Pakistan ranked 139 out of 180), and enjoyed the highest ranking of any South Asian country in the World Bank’s 2010 Doing Business report.

At the same time, the Pakistani state repeatedly fails to provide basic services to its population – not just in the tribal areas, but also in cities like Karachi, where 30,000 people die each year from consuming unsafe water.

Where basic services are provided, Islamabad favors wealthy, landed, and politically connected interests over those of the most needy – the very people with the most desperate need for international aid. Last year, government authorities established a computerized lottery that was supposed to award thousands of free tractors to randomly selected small farmers across Pakistan. However, among the “winners” were large landowners – including family members of a Pakistani parliamentarian.

Working through Islamabad on aid provision is essential. However, the United States also needs to diversify its aid partners in Pakistan.

For starters, Washington should look within civil society. This rich and vibrant sector is greatly underappreciated in Washington. The Hisaar Foundation, for example, is one of the only organizations in Pakistan focusing on water, food, and livelihood security.

The country’s Islamic charities also play a crucial role. Much of the aid rendered to health facilities and schools in Pakistan comes from Muslim welfare associations. Perhaps the most well-known such charity in Pakistan – the Edhi Foundation – receives tens of millions of dollars each year in unsolicited funds.

Washington should also be targeting venture capital groups. The Acumen Fund is a nonprofit venture fund that seeks to create markets for essential goods and services where they do not exist. The fund has launched an initiative with a Pakistani nonprofit organization to bring water-conserving drip irrigation to 20,000-30,000 Pakistani small farmers in the parched province of Sindh.

Such collaborative investment is a far cry from the opaque, exploitative foreign private investment cropping up in Pakistan these days – particularly in the context of agricultural financing – and deserves a closer look.

With all the talk in Washington about developing a strategic dialogue with Islamabad and ensuring the latter plays a central part in U.S. aid provision to Pakistan, it is easy to forget that Pakistan’s 175 million people have much to offer as well. These ample human resources – and their institutions in civil society – should be embraced and be better integrated into international aid programs.

While Pakistan’s rapidly growing population may be impoverished, it is also tremendously youthful. If the masses can be properly educated and successfully integrated into the labor force, Pakistan could experience a “demographic dividend,” allowing it to defuse what many describe as the country’s population time bomb.

A demographic dividend in Pakistan, the subject of an upcoming Wilson Center conference, has the potential to reduce all of Pakistan’s threats – and to enable the country to move away from its deep, but very necessary, dependence on international aid.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Photo Credit: Water pipes feeding into trash infected waterway in Karachi, courtesy Flickr user NB77. -

Securing Food in Insecure Areas

›May 25, 2010 // By Dan Asin“Of the 1 billion people who are in food-stressed situations today, a significant proportion live in conflict-ridden countries,” said Raymond Gilpin of the U.S. Institute of Peace at last Thursday’s launch of USAID’s Feed the Future initiative. “Most of them live in fear for their lives, in uncertain environments, and without clear hope for a better tomorrow.”

According to data from the World Food Programme and the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Database, of the countries with moderately to very high hunger rates in 2009, nearly a quarter experienced violent conflict in the previous year, and nearly half in the preceding two decades.

Gilpin said those working toward food security need to develop “conflict-sensitive” approaches, because “a lot of fundamentals that underlie this problem have a lot to do with conflict.” He noted several points, from production to purchasing power, at which conflict enters to disrupt the farm to mouth food cycle:- Production: Be it forced or voluntary, internal or external, conflict often results in displacement. Farmers are not exempt, and when they’re not on their land they cannot produce.

- Delivery: “Food security isn’t always an issue of food availability; it’s an issue of accessibility,” he said. “When violent conflict affects a community or a region…it destroys infrastructure and weakens institutions.”

- Market access: In conflict zones, it is solitary or competing armed contingents, rather than the market’s invisible hand, that control access to supplies. “Groups who usually have the monopoly of force, control livelihoods and food and services,” he said.

- Purchasing power: Conflict disrupts economic activity, degrading both incomes and real wealth. Those remaining in the conflict area suffer from fewer opportunities to conduct business, while those choosing to migrate relinquish their assets. In instances where food is available to purchase, conflict reduces the number of individuals who can afford it.

Photo Credit: World Food Programme distribution site in Afghanistan, courtesy Flickr user USAID Afghanistan. -

USAID’s Shah Focuses on Women, Innovation, Integration

›May 20, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffWomen in developing countries are “core to success and failure” of USAID’s plan to fight hunger and poverty, and “we will be focusing on women in everything we do,” said USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah at today’s launch of the “Feed the Future” guide.

But to solve the “tough problem” of how to best serve women farmers, USAID needs to “take risks and be more entrepreneurial,” said Shah, as it implements the Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative.

“A lot of this is going to fail and that’s OK,” Shah said, calling for a “culture of experimentation” at the agency. He welcomed input from the private sector, which was represented at the launch by Des Moines-based Pioneer Hi-Bred.

In one “huge change in our assistance model,” Feed the Future will be “country-led and country-owned,” said Shah, who asked NGOs and USAID implementing partners to “align that expertise behind country priorities” and redirect money away from Washington towards “building real local capacity.” USAID will “work in partnership, not patronage,” with its 20 target countries, he said.

To insure that the administration’s agricultural development efforts are aligned to the same goals, Shah said USAID will collect baseline data from the start on three metrics: women’s incomes, child malnutrition, and agricultural production.

“Whether it is finance, land tenure, public extension, or training efforts, it does not matter whether it is an ‘agricultural development’ category of program,” said Shah. All programs will “provide targeted services to women farmers.”

While Shah briefly mentioned integrating these efforts with the administration’s Global Health Initiative, he only gave one example. Nutrition programs would be tied to health “platforms that already exist at scale” in country, such as HIV, malaria, vaccination, and breastfeeding promotion programs, he said.

Targeting Food Security: The Wilson Center’s Africa Program Takes Aim

If “food supplies in Africa cannot be assured, then Africa’s future remains dismal, no matter how efforts of conflict resolution pan out or how sustained international humanitarian assistance becomes,” says Steve McDonald, director of the Wilson Center’s Africa Program, in the current issue of the Wilson Center’s newsletter, Centerpoint. “It sounds sophomoric, but food is essential to population health and happiness—its very survival—but also to productivity and creativity.”

The May 2010 edition of Centerpoint highlights regional integration, a key focus of U.S. policy, as a mechanism for assuring greater continuity and availability of food supplies. Drawing on proceedings from the Africa Program’s “Promoting Regional Integration and Food Security in Africa” event held in March, Centerpoint accentuates key conclusions on building infrastructure and facilitating trade.

Photo Credit: “USAID Administrator Shah visits a hospital in Haiti” courtesy Flickr user USAID_Images. -

Coffee and Contraception: Combining Agribusiness and Community Health Projects in Rwanda

›“Population pressures and diminishing land holdings – due to high fertility rates, war and genocide, and subsequent migration – have caused a rapid decrease in the forested and protected areas and increased soil infertility and food insecurity” in Rwanda, USAID’s Irene Kitzantides told a Wilson Center audience.

Kitzantides, a population, health, and environment advisor and global health fellow, said “the population is projected to reach over 14 million by 2025” – nearly one-third more than today, due to the country’s high fertility rate of nearly 5.5 children per women–which could continue to negatively impact forests and food supplies.

In response to these challenges, USAID supported the Sustaining Partnerships to Enhance Rural Enterprise and Agribusiness Development (SPREAD) Project. SPREAD uses an integrated population-health-environment (PHE) approach to develop the coffee agribusiness and bring family planning, HIV/AIDS, and reproductive health services to coffee workers.

Combining income generation with health services was thought an effective way to “fulfill the overall SPREAD goal of improving lives and livelihoods,” said Kitzantides.

A SPREADing Mandate: Integrating Health and Agribusiness

SPREAD follows USAID’s PEARL I and II Projects, which focused exclusively on agricultural development. Coffee is still at the center of SPREAD’s activities, with $5 million of the project’s $6 million USAID budget earmarked for agricultural development.

However, a broader mandate to include health services emerged after recognition that greater income alone does not ensure greater quality of life. The additional health funding leverages SPREAD’s already established relationships with farming cooperatives to bring health services to traditionally underserved rural communities.

“We really tried to build on the existing assets of the cooperative,” said Kitzantides. “We also really tried to complement local and national public health policy and partners.”

The integration of health with agricultural goals, and the use of already established in-country health programs, has made SPREAD extremely cost-effective, with HIV/AIDS prevention education costing less than $2 per person.

Examples of SPREAD’s integrated work include:Combined health and agricultural lessons: Kitzantides and her colleagues trained nearly 400 animateurs de café, cooperative employees running the agricultural education programs, to incorporate public health objectives into their activities. Combining health and agricultural education into one session takes advantage of workers already trained during previous USAID programs. The combination also attracts more male participants, who traditionally shunned HIV/AIDS, family planning, and reproductive health campaigns and services.

Radio programming: SPREAD worked with the agricultural radio program Imbere Heza (“Bright Future”) to incorporate health messaging at the end of each program.

Mobile clinics: SPREAD works with cooperatives and local health centers to bring convenient services to farmers when they gather at sales or processing stations during harvests.

Mobile clinics: SPREAD works with cooperatives and local health centers to bring convenient services to farmers when they gather at sales or processing stations during harvests.Community theater: SPREAD hires local theater groups to perform skits on health. The farming communities “really love community theater and always ask for it,” said Kitzantides.

In its relatively short existence, SPREAD’s health activities have reached over 120,000 people with HIV/AIDS prevention messages; nearly 90,000 with messages discussing family planning/reproductive health; and almost 40,000 about maternal and child health. The project counts 347 women as new users of family planning services.

Lessons learned – which will be examined in more detail in an upcoming issue of Focus – include the importance of using community-based approaches to overcome perceived social barriers; the advantages of integrating cross-cutting activities at the outset of a program; and the need for strong monitoring and evaluation systems to measure the effort’s outcomes. Jason Bremner of the Population Research Bureau said PHE projects such as SPREAD go “beyond what the health sector itself can do and find new ways of reaching underserved remote populations.” He presented a soon-to-be-released PRB map plotting the location of more than 40 PHE projects in Africa.

Jason Bremner of the Population Research Bureau said PHE projects such as SPREAD go “beyond what the health sector itself can do and find new ways of reaching underserved remote populations.” He presented a soon-to-be-released PRB map plotting the location of more than 40 PHE projects in Africa.

The success of SPREAD and similar projects demonstrates the potential for PHE approaches to bring reproductive health and family planning services to rural areas, Bremner noted, but there is still much work to be done to scale up this integrated approach – and to document its successes.

Sustaining SPREAD

Kitzantides said it took several years to integrate health activities with the already established agricultural programs. Since USAID funding for the program is scheduled to end in 2011, she is uncertain that the time remaining will be enough for SPREAD’s health partners to develop the logistical and financial capacities to become self-sustaining. But SPREAD has changed attitudes and beliefs, two key objectives that do not require sustained funding.

“We used to talk about growing coffee, making money, buying material things like bikes – not about problems like malaria, HIV/AIDS, etc.,” said one SPREAD agricultural business manager during the program’s evaluation. “Someone could have 5 million Rwandan francs in the house but could suffer from malaria where medicine costs 500 Rwandan francs, due to ignorance. You have to teach people about production, you have to also think of their health to improve their lives.”

Photo Credits: Irene Kitzantides, courtesy David Hawxhurst; condom demonstration, courtesy Nick Fraser; community theater group, courtesy SPREAD Health Program; Jason Bremner, courtesy David Hawxhurst. -

As Somalia Sinks, Neighbors Face a Fight to Stay Afloat

›May 14, 2010 // By Schuyler NullThe week before the international Istanbul conference on aid to Somalia, the UN’s embattled envoy to the country, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, warned the Security Council that if the global community “did not take the right action in Somalia now, the situation will, sooner or later, force us to act and at a much higher price.”

The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) also issued strong warnings this week. Deputy High Commissioner Alexander Aleinikoff said in Geneva, “The displacement crisis is worsening with the deterioration of the situation inside Somalia and we need to prepare fast for new and possibly large-scale displacement.”

But the danger is not limited to Somalia. The war-torn country’s cascading set of problems – criminal, health, humanitarian, food, and environmental – threaten to spill over into neighboring countries.

A Horrendous Humanitarian Crisis

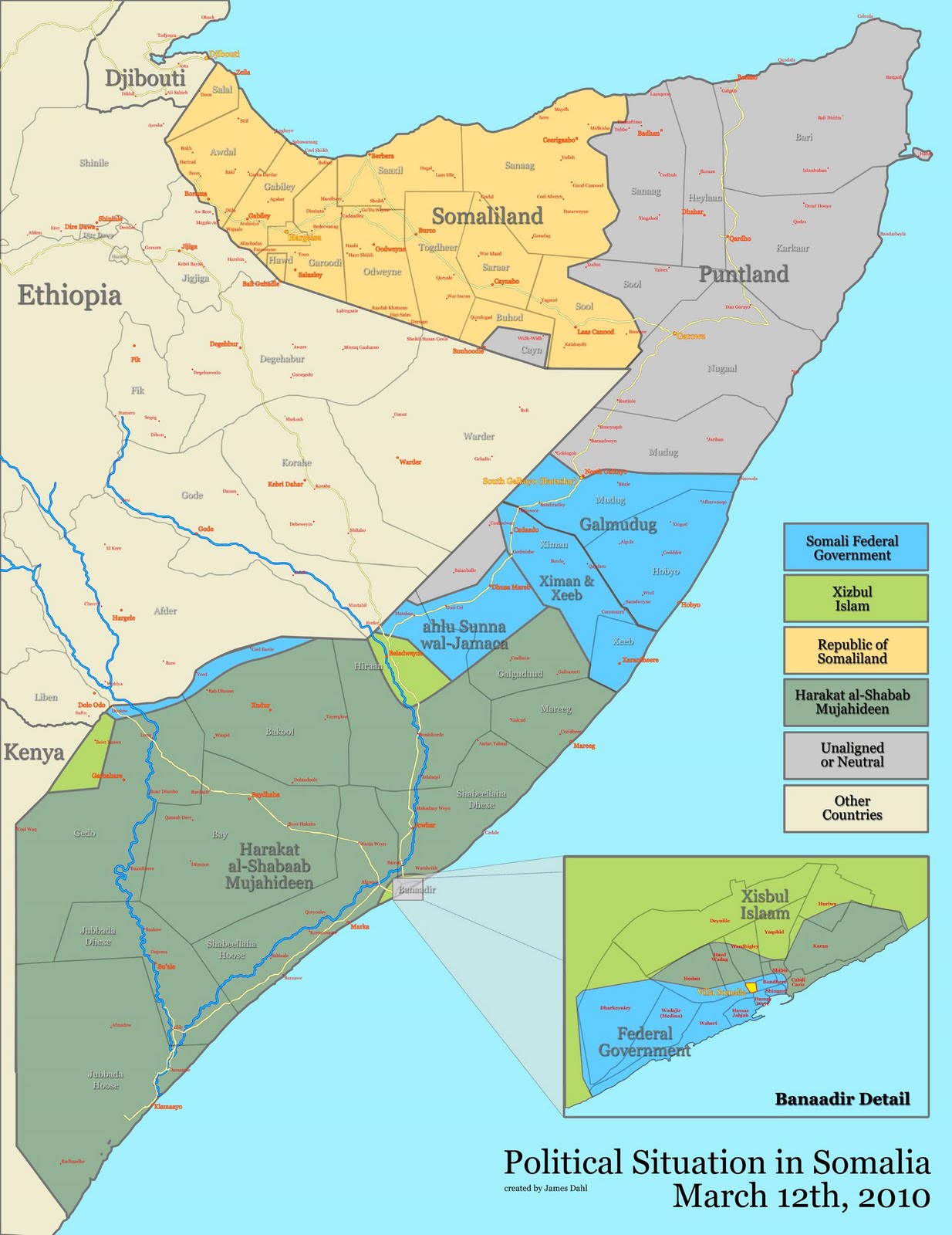

The UN- and U.S.-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) controls only parts of Mogadishu and small portions of central Somalia, while insurgent group Al Shabab controls nearly the entire south. The northern area is divided into semi-autonomous Somaliland and Puntland, which also fall outside of the transitional government’s control.

But the civil war is only one part of what Ould-Abdallah called a “horrendous” humanitarian crisis.

According to the UN, 3.2 million Somalis rely on foreign assistance for food – 43 percent of the population – and 1.4 million have been internally displaced by war. Another UN-backed study finds that approximately 50 percent of women and 60 percent of children under five are anemic. Most distressing, the UN Security Council reported in March that up to half of all food aid sent to Somalia is diverted from people in need by militants and corrupt officials, including UN and government employees.

Because of the country’s large youth bulge – 45 percent of Somalia’s population is under the age of 15 – food and health conditions are expected to get much worse before they get better. In the 2009 Failed States Index, Somalia ranks as the least stable state in the world and, along with Zimbabwe, has the highest demographic pressures.

Islamic Militants and the Battle for the High Seas

Yet the West continues to focus on the sensational pirate attacks on Somalia’s coast. The root cause of these attacks is not simply lawlessness say Somali officials, instead, they began partly as desperate attempts to stop foreign commercial fleets from depleting Somalia’s tuna-rich, lawless shores. A 2006 High Seas Task Force reported that at any given time, “some 700 foreign-owned vessels are engaged in unlicensed and unregulated fishing in Somali waters, exploiting high value species such as tuna, shark, lobster and deep-water shrimp.”

The transitional government opposes the fishermen-turned-pirates, but can do little to stop them. Al Shabab has thus far allowed pirates to operate freely in their territory. Their tacit approval may be tied to reports that the group has received portions of ransoms in the past.

Another hardline Islamist group, Hizbul Islam, recently took over the pirate safe haven of Haradhere, allegedly in response to local pleas for better security, but the move may simply have been part of an ongoing struggle with Al Shabab for control of pirate ransoms and port taxes – one of the few sectors of the economy that has remained lucrative.

“I can say to you, they are not different from pirates — they also want money,” Yusuf Mohamed Siad, defense minister with Somalia’s TFG, told Time Magazine.

A Toxic ThreatInitially the pirates claimed one of their goals was to ward off “mysterious European ships” that were allegedly dumping barrels of toxic waste offshore. UN envoy Ould-Abdallah told Johann Hari of The Independent in 2009 that “somebody is dumping nuclear material here. There is also lead, and heavy metals such as cadmium and mercury – you name it.” After the 2005 tsunami, “hundreds of the dumped and leaking barrels washed up on shore. People began to suffer from radiation sickness, and more than 300 died,” Hari reports.

Finnish Minister of Parliament Pekka Haavisto, speaking to ECSP last year, urged UN investigation of the claims. “If there are rumors, we should go check them out,” said the former head of the UN Environment Program’s Post-Conflict Assessment Unit:I think it is possible to send an international scientific assessment team in to take samples and find out whether there are environmental contamination and health threats. Residents of these communities, including the pirate villages, want to know if they are being poisoned, just like any other community would.

To date, there has been no action to address these claims.

Drought, Deforestation, and Migration

While foreign entities may have been exploiting Somalia’s oceans, the climate has played havoc with the rest of the country. Reuters and IRIN report that the worst drought in a decade has stricken some parts of the interior, while others parts of the country face heavy flooding from rainfall further upstream in Ethiopia.

Land management has also broken down. A 2006 Academy for Peace and Development study estimated that the province of Somaliland alone consumes up 2.5 million trees each year for charcoal, which is used as a cheaper alternative to gas for cooking and heating. A 2004 Somaliland ministry study on charcoal called the issue of deforestation for charcoal production “the most critical issue that might lead to a national environmental disaster.”

West of Mogadishu, Al Shabab has begun playing the role of environmental steward, instituting a strict ban on all tree-cutting – a remarkable decree from a group best known for their brutal application of Sharia law rather than sound governance.

The result of this turmoil is an ever-increasing flow of displaced people – nearly 170,000 alone so far this year, according to the Washington Post – driven by war, poverty, and environmental problems. The burden is beginning to weigh on Somalia’s neighbors, says the UNHCR.

The Neighborhood Effect

One of the largest flows of displaced Somalis is into the Arabian peninsula country of Yemen – itself a failing state, with 3.4 million in need of food aid, 35 percent unemployment, a massive youth bulge, dwindling water and oil resources, and a burgeoning Al Qaeda presence.

In testimony on Yemen earlier this year, Assistant Secretary of State Jeffrey Feltman said that the country’s demographics were simply unsustainable:Water resources are fast being depleted. With over half of its people living in poverty and the population growing at an unsustainable 3.2 percent per year, economic conditions threaten to worsen and further tax the government’s already limited capacity to ensure basic levels of support and opportunity for its citizens.

Other neighboring countries face similar crises of drought, food shortage, and overpopulation – Ethiopia has 12 million short of food, Kenya, 3.5 million, says Reuters. UNHCR reports that in Djibouti, a common first choice for fleeing Somalis, the number of new arrivals has more than doubled since last year, and the country’s main refugee camp is facing a serious water crisis.

A Case Study in Collapse

The ballooning crises of Somalia encompass a worst-case scenario for the intersection of environmental, demographic, and conventional security concerns. Civil war, rapid population growth, drought, and resource depletion have not only contributed to the complete collapse of a sovereign state, but could also lead to similar problems for Somalia’s neighbors – threatening a domino effect of destabilization that no military force alone will be able to prevent.

Speaking at a naval conference in Abu Dhabi this week, Australian Vice Admiral Russell Crane told ASD News that, “The symptoms (piracy) we’re seeing now off Somalia, in the Gulf of Aden, are clearly an outcome of what’s going on on the ground there. As sailors, we’re really just treating the symptoms.”

Sources: Academy for Peace and Development, AP, ASD News, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, High Seas Task Force, Independent, IRIN, New York Times, Population Action, Population Reference Bureau, Reuters, Telegraph, Time, UN, US State Department, War is Boring, Washington Post.

Photo Credits: “Don’t Swim in Somalia (It’s Toxic)” courtesy of Flickr user craynol and “Somalia map states regions districts” courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. -

The Food Security Debate: From Malthus to Seinfeld

›Charles Kenny’s latest article, “Bomb Scare: The World Has a Lot of Problems; an Exploding Population Isn’t One of Them” reminds me of a late-night episode of Seinfeld: a re-run played for those who missed the original broadcast. Kenny does a nice job of filling Julian Simon’s shoes. What’s next? Will Jeffrey Sachs do a Paul Ehrlich impersonation? Oh, Lord, help me; I hope not.

I’ve already seen the finale. Not the one where Jerry, George, and Kramer go to jail — the denouement of the original “Simon and Ehrlich” show. After the public figured out that each successive argument (they never met to debate) over Malthus’s worldview was simply a rehash of the first — a statement of ideology, rather than policy — they flipped the channel.

Foreign Policy could avoid recycling this weary and irrelevant 200-year-old debate by instead exploring food security from the state-centric perspective with which policymakers are accustomed. While economists might hope for a seamless global grain production and food distribution system, it exists only on their graphs.

Cropland, water, farms, and markets are still part and parcel of the political economy of the nations in which they reside. Therefore they are subject to each state’s strategic interests, political considerations, local and regional economic forces, and historical and institutional inefficiencies.

From this realistic perspective, it is much less important that world population will soon surpass 7 billion people, and more relevant that nearly two dozen countries have dropped below established benchmarks of agricultural resource scarcity (less than 0.07 hectares of cropland per person, and/or less than 1000 cubic meters of renewable fresh water per person).

Today, 21 countries—with some 600 million people—have lost, for the foreseeable future (and perhaps forever), the potential to sustainably nourish most of their citizens using their own agricultural resources and reasonably affordable technological and energy inputs. Instead, these states must rely on trade with–and food aid from–a dwindling handful of surplus grain producers.

By 2025, another 15 countries will have joined their ranks as a result of population growth alone (according to the UN medium variant projection). By then, about 1.4 billion people will live in those 36 states—with or without climate change.

For the foreseeable future, poor countries will be dependent on an international grain market that has recently experienced unprecedented swings in volume and speculation-driven price volatility; or the incentive-numbing effects of food aid. As demand rises, the poorest states spend down foreign currency reserves to import staples, instead of using it to import technology and expertise to support their own economic development.

Meanwhile, wealthier countries finding themselves short of water and land either heavily subsidize local agriculture (e.g., Japan, Israel, and much of Europe) or invest in cropland elsewhere (e.g., China, India, and Saudi Arabia). And some grain exporters—like Thailand—decided it might be safer to hold onto some of their own grain to shield themselves from a future downturn in their own harvest. All of this is quite a bit more complex than either Malthus could have imagined or Kenny cares to relate.

It hardly matters why food prices spiked and remained relatively high—whether it is failed harvests, growing demand for grain-fed meat, biofuels, profit-taking by speculators, or climate change. Like it or not, each has become an input into those wiggly lines called grain price trends, and neither individual states nor the international system appears able or willing to do much about any of them.

From the state-centric perspective, hunger is sustained by:1. The state’s inability or lack of desire to maintain a secure environment for production and commerce within its borders;

In some countries, aspects of population age structure or population density could possibly affect all three. In others, population may have little effect at all.

2. Its incapacity to provide an economic and trade policy environment that keeps farming profitable, food markets adequately stocked and prices reasonably affordable (whether produce comes from domestic or foreign sources); and

3. Its unwillingness or inability to supplement the diets of its poor.

What bugs me most about Kenny’s re-run is its disconnect with current state-centric food policy concerns, research, and debates (even as the U.S. administration and Congress are focusing on food security, with a specific emphasis on improving the lives of women.—Ed.).

Another critique of Malthus’s 200-year-old thesis hardly informs serious policy discussions. Isn’t Foreign Policy supposed to be about today’s foreign policy?

Richard Cincotta is a consultant with the Environmental Change and Security Program and the demographer-in-residence at the H.L. Stimson Center in Washington, DC.

Photo Credit “The Bombay Armada” courtesy of Flickr user lecercle. -

DOD Measures Up On Climate Change, Energy

›May 5, 2010 // By Schuyler Null“As Congress deliberates its role, DOD is moving ahead steadily on a broad range of energy and climate initiatives,” says former Senator John Warner in a recent Pew report, Reenergizing America’s Defense: How the Armed Forces Are Stepping Forward to Combat Climate Change and Improve the U.S. Energy Posture.

The military as a leader and catalyst for renewable energy was a key focus of the recently released Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), which for the first time included consideration of the effects of climate change and excessive energy consumption on military planning:Assessments conducted by the intelligence community indicate that climate change could have significant geopolitical impacts around the world, contributing to poverty, environmental degradation, and the further weakening of fragile governments. Climate change will contribute to food and water scarcity, will increase the spread of disease and may spur or exacerbate mass migration.

According to the Pew report, the Department of Defense has set a goal of producing or procuring at least 25 percent of its non-tactical electric energy needs from renewable sources by 2025. Highlights of the service’s efforts include:

The Pew report offers a generally favorable appraisal of the military’s response to the “twin threats of energy dependence and climate change” and the progress made towards reaching federal energy mandates. However, the authors let slide that the overwhelming amount of DOD energy usage is tied to tactical consumption, which has been given inadequate attention thus far (consider that the senior Pentagon official overseeing tactical energy planning was only just appointed, although the position has existed since October 2008).- The U.S. Navy’s “Great Green Fleet” carrier strike group, which will run entirely on alternative fuels and nuclear power by 2016;

- The construction of a 500-megawatt solar facility in Fort Irwin, California by the U.S. Army which will help the base reach ‘net-zero plus’ status;

- The goal of acquiring 50 percent of the U.S. Air Force’s aviation fuels from biofuel blends by 2016;

- The U.S. Marine Corps’ 10×10 campaign to develop a comprehensive energy strategy and meet ten goals aimed at reducing energy and water intensity and increasing the use of renewable electric energy by the end of 2010.

Interest in this field has grown quickly, as evidenced by the more than 400 people gathered at the launch of the latest report from the Center for New American Security (CNAS), Broadening Horizons: Climate Change and the U.S. Armed Forces – a big increase from the 50 or so at CNAS’ first natural security event in June 2008.

The CNAS study, much like the Pew report, breaks down the military’s efforts by service, but the study’s authors – including U.S. Navy Commander Herbert E. Carmen – thankfully provide more specific recommendations for what could be done better.

Based on research, interviews, and site visits, the study offers geographically specific recommendations for each of the Unified Commands, as well as seven broad recommendations for DOD as a whole:

“While we believe there is still much work ahead, there is a growing commitment to addressing energy and climate change within the DOD,” said USN Commander Carmen in the report:- In light of its implications for the global commons, ensure that DOD is included in the emerging debate over geoengineering.

- Urge U.S. ratification of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in order to provide global leadership and protect U.S. and DOD interests, especially in the context of an opening Arctic sea.

- Eliminate the divided command over the Arctic and assign U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) as the supported commander.

- The U.S. government should make an informed decision about constructing nuclear reactors on military bases and provide clear policy guidelines to DOD.

- Congress and DOD should move away from the “cost avoidance” structure of current renewable energy, conservation, and efficiency practices in order to reward proactive commanders and encourage further investment.

- All of the services should improve their understanding of how climate change will effect their missions and capabilities; e.g. migration and water issues may impact Army missions, a melting Arctic, the Navy.

- The Air Force should fully integrate planning for both energy security and climate change into a single effort.

Indeed, in our conversation with officials in the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy, it was clear that, in developing the climate change and energy section of the 2010 QDR, the Department of Defense has developed a nascent, intellectual infrastructure of civilian and military professionals who will continue to study the national security implications of climate change, and, we hope, will continue to reevaluate climate change risks and opportunities as the science continues to evolve.

A holistic view of national security that includes energy and environment, as well as demographic and development inputs, continues to gain traction as an important driver in DOD policy and planning.

Photo Credit: “Refueling at FOB Wright” courtesy of Flickr user The U.S. Army.

Showing posts from category development.