-

Annie Murphy, International Reporting Project

Mozambique Coal Mine Brings Jobs, Concerns

›May 31, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Annie Murphy appeared on the International Reporting Project and NPR (follow the links for the accompanying audio track as well). Murphy appeared with three other IRP fellows at the Wilson Center on April 28 to talk about their experiences reporting abroad.

As developing countries grow, their need for raw materials grows, too.

This is the case for Brazil, a country that has much in common with the nation of Mozambique: Both have a mix of African and Portuguese influences; both are rich in natural resources; and both fought long and hard to throw off European colonialism.

Today, however, a Brazilian coal mine in Mozambique has some wondering what the energy demands of growing economies like Brazil really mean for African countries like Mozambique.

This coal mine in northwestern Mozambique is owned by the Brazilian company Vale — it’s a gaping, dark gray pit in the middle of a green, windswept savannah. Still under construction, it currently employees about 7,500 people.

Jose Manuel Guilengue, 23, a machine operator, says that he and a friend traveled 1,000 miles from the capital to get there, where they were both hired. That was a year ago. He now makes around $400 a month — which is more than four times the average salary in Mozambique.

According to the general manager overseeing construction, Osvaldo Adachi, this mine will produce about 11 million tons of coal each year, for at least three decades.

Continue reading and listen to the audio at the International Reporting Project.

Annie Murphy reported this story during a fellowship with the International Reporting Project (IRP). To hear more about Murphy and the IRP program, see the event summary for “Reporting on Global Health: A Conversation With the International Reporting Project Fellows.”

Photo Credit: Adapted from Mozambique, courtesy of flickr user F H Mira. -

Environmental Action Plans in Darfur: Improving Resilience, Reducing Vulnerability

›Many villagers in Baaba, a community of 600 in South Darfur, remember a shady forest of mango and guava trees that provided food and a valuable income for the villagers and a pleasant picnic spot for people in Nyala, the nearby state capital. Over the last decade, that forest has degraded into eroded brush dotted by the occasional baobab – a transformation that is unfortunately a familiar sight throughout Darfur.

Most of Baaba’s trees have become firewood and charcoal for the people living in nearby internally displaced persons (IDP) camps. Baaba’s residents, who themselves returned from the camps to try to rebuild their lives at home, struggle to coax enough food from the soil, which has largely eroded away following deforestation. Afraid to venture any further than necessary from home for fear of violence and banditry in the countryside, they farm and graze the same land year after year without fallow periods – further depleting the soil and driving yields ever lower.

Baaba is like hundreds of Darfuri villages, which face a brutal mix of insecurity and environmental decline that leaves them one poor harvest away from being forced into the IDP camps. Baaba, however, is also a pilot participant in a new approach – the Community Environmental Action Plan – that aims to rehabilitate the local environment, enable people to sustainably manage natural resources, and ultimately to make communities more prosperous and resilient.

Most of Darfur has always been marginal land where farming and herding provide a meager livelihood and natural resources are few. Even before war broke out in 2003, soaring population growth (total population has quintupled since the 1970s) was putting intolerable pressure on the land, water, and trees of Darfur. The conflict in Darfur has since heavily disrupted traditional methods for sharing and maintaining natural resources, leading to environmental devastation. The worsening effects of climate change – though hard to separate from local environmental depletion – are also beginning to disrupt weather patterns and farming. The disheartening result is that even where fighting has subsided and displaced persons return home, they often find that the land no longer sustains them.

Traditional humanitarian aid and infrastructure projects are ill-suited to help, since persistent insecurity deprives humanitarian actors of access to communities for weeks or months at a time. Environmental decline didn’t start the humanitarian crisis in Darfur, but it threatens to prolong it and put a sustainable peace out of reach.

Community Environmental Action Plans

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), mandated to work on IDP and return issues in Darfur, aimed to address these challenges with Community Environmental Action Plans (CEAPs) in three pilot villages. CEAPs build comprehensive local capacity, enabling communities to manage natural resources sustainably and address environmental problems themselves without relying on outside support. The ultimate goal is to build the resilience and adaptive capacity of vulnerable communities. IOM worked with Baaba and two other villages to implement CEAPs, in partnership with the Swiss-based environmental NGO ProAct, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the government of South Darfur, and Darfuri environmental organizations. The project, funded by the Government of Japan, ran from early 2009 until mid-2010.

The CEAP process trains communities to understand the connections between a healthy ecosystem and a prosperous community and to promote livelihoods by rehabilitating the environment. Each participating village formed a CEAP governance committee, which was then trained to understand the environment as a single integrated system and to see how damaging one resource like trees can devastate other ecosystem services – such as pollination, groundwater retention, and soil fertility – that enable and promote human livelihoods. The communities then identified essential needs, including reforestation, water harvesting, and improved sanitation, and worked with IOM to develop appropriate responses. These activities were all implemented by the villages themselves, with technical and material support from IOM and its partners.

Building Local Capacity

The communities built low-tech but highly productive tree nurseries, producing and planting over 200,000 seedlings to restore damaged land and provide a sustainable wood supply. Local women learned how to make highly fuel-efficient stoves using locally available materials, cutting their need for firewood and allowing them to sell stoves in the nearby Nyala market. Farmers received extensive training in sustainable agriculture techniques, including water harvesting, composting, agro-forestry, and intercropping (mixing complementary plant species together in the same fields). Volunteers were trained in effective hygiene practices and built latrines for each household. Water committees were trained to repair and maintain the villages’ indispensable but fragile water hand pumps, ensuring a more reliable source of drinking water. Each of these activities was governed by a community committee, including women and youth, trained to manage the projects for the benefit of the entire community and continue the work after the project’s end.

Farmers received extensive training in sustainable agriculture techniques, including water harvesting, composting, agro-forestry, and intercropping (mixing complementary plant species together in the same fields). Volunteers were trained in effective hygiene practices and built latrines for each household. Water committees were trained to repair and maintain the villages’ indispensable but fragile water hand pumps, ensuring a more reliable source of drinking water. Each of these activities was governed by a community committee, including women and youth, trained to manage the projects for the benefit of the entire community and continue the work after the project’s end.

Through this approach, all three villages significantly boosted their livelihoods and agricultural productivity while becoming less dependent on the unsustainable exploitation of their fragile environment. The CEAP approach benefits greatly from focusing on capacity-building and local implementation, which fosters a strong sense of community ownership that persists after the project ends. Equally important, CEAPs attempt to address most or all of a community’s environmental issues simultaneously, reducing the risk that neglected environmental problems – particularly agricultural failure – will critically destabilize and displace a community in the future.

A Replicable Model

CEAPs aren’t a panacea, particularly in the conflict-prone areas where they are most needed. Insecurity, particularly a series of abductions of humanitarian workers from several organizations in 2010, cut off IOM’s access to the communities late in the project. Though the core activities were completed by working through local partners with more reliable access, the security situation left few opportunities for follow-up activities. Longer-term threats, particularly unrestrained population growth – which requires a comprehensive approach that includes addressing unmet need for family planning services – could undo much of the good that CEAPs accomplish.

Though insecurity prevented IOM from continuing the project, other organizations including UNEP are implementing and refining the CEAP approach elsewhere in Darfur and other regions in sub-Saharan Africa. As climate changes intensifies and the potential for related conflicts looms, the CEAP approach should be considered as a powerful and flexible tool to rehabilitate the environment and strengthen vulnerable communities.

Paul Rushton is a consultant for the International Organization for Migration, Sudan, and worked as a Programme Officer managing the CEAP projects in South Darfur from 2009 to 2010.

Sources: International Organization for Migration, UN.

Photo Credit: Camels graze in a destroyed and degraded village in Western Darfur, courtesy of UNEP; and pictures from CEAP sites in Southern Darfur, courtesy of Paul Rushton. -

Meeting Half the World’s Fuel Demands Without Affecting Farmland Joan Melcher, ChinaDialogue

Biofuels: The Grassroots Solution

›May 24, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Joan Melcher, appeared on ChinaDialogue.

The cultivation of biofuels – fuels derived from animal or plant matter – on marginal lands could meet up to half of the world’s current fuel consumption needs without affecting food crops or pastureland, environmental engineering researchers from America’s University of Illinois have concluded following a three-year study. The findings, according to lead author Ximing Cai, have significant implications not only for the production of biofuels but also the environmental quality of degraded lands.The study, the final report of which was published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology late last year, comes at a time of increasing global interest in biomass. The International Energy Agency predicts that biomass energy’s share of global energy supply will treble by 2050, to 30 percent. In March, the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development called on national governments to take a “more sophisticated” approach to the energy source, putting it at the heart of energy strategies and ramping up investment in new technologies and research programs.

The University of Illinois project used cutting-edge land-use data collection methods to try to determine the potential for second-generation biofuels and perennial grasses, which do not compete with food crops and can be grown with less fertilizer and pesticide than conventional biofuels. They are considered to be an alternative to corn ethanol – a “first generation” biofuel – which has been criticized for the high amount of energy required to grow and harvest it, its intensive irrigation needs and the fact that corn used for biofuel now accounts for about 40 percent of the United States entire corn crop.

A critical concept of the study was that it only considered marginal land, defined as abandoned or degraded or of low quality for agricultural uses, Cai, who is civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Illinois in the mid-western United States, told ChinaDialogue.

The team considered cultivation of three crops: switchgrass, miscanthus, and a class of perennial grasses referred to as low-impact high-diversity (LIHD).

Continue reading on ChinaDialogue.

Sources: Sources: International Energy Agency, Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, Reuters, University of Illinois.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Biofuels,” courtesy jurvetson. -

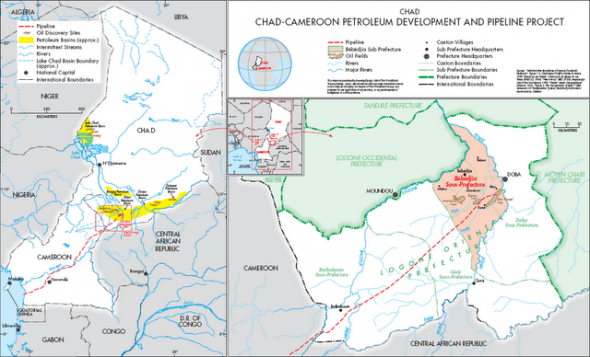

World Bank Pipeline Project in Chad Reveals Development Challenges

›This scholar spotlight was originally featured in the Wilson Center’s Centerpoint, February 2011.

In 2000, the governments of Chad and Cameroon teamed up with a three-company oil consortium, with the help of a World Bank loan, to begin building an oil pipeline. By 2003, oil revenues were flowing. This multi-billion dollar pipeline project, which transports oil from Chad through a 640-mile underground pipeline in neighboring Cameroon, is one of Africa’s largest public-private development projects.“Unfortunately, the project fell short on its social and development-oriented objectives,” said Wilson Center Fellow Lori Leonard.

One of the World Bank’s conditions on granting the loan was compensation for the involuntary resettlement this project would cause. However, Leonard said, the World Bank failed to understand, or take into account, social norms around land use and property relations.

“The compensation plan introduced the idea of private property but there was no institutional or legal framework for it,” she said. “This led to a flood of disputes over land and created breaks in the social safety net and societal fabric in Chad.” Uprooting people led to unprecedented problems, from the loss of land and livelihoods to disputes over compensation payments.

The reality was that in Chad, one of the world’s poorest countries, about a quarter-million people were affected. “People in the oilfield region, like people everywhere, are deeply attached to the place where they live – tied to their land,” Leonard said. Suddenly, their property became monetized. “They were asked to think differently about crops, trees, kitchen gardens, everyday objects,” as everything was given a monetary value.

But all the land was populated so there was nowhere to move to and no other trade or skill to easily adopt. “The pipeline project did not create a local economy, that could absorb people who became land poor,” she said.

The World Bank, which withdrew from the project in 2008 when Chad paid off the loan, accused Chad of misspending oil revenues, but that is just part of the story, said Leonard. The problem is not purely economic. “The economy is not outside of society,” Leonard said. “[This project] put a market value on everyday objects and that reshapes societal relations. And it raises the ethical question: ‘How do I live now?’”

In Chad, a largely agrarian economy, large parcels of land became oil fields, wells, and pumping and collection stations.

“Fields were taken or divided up into small fragments and the people wonder what to do next,” said Leonard. “Fertility rates are high and each successive generation will have to divide up [smaller and smaller amounts of] land. And there is already incredible pressure on the land now. The soil is poor but there is not enough [viable land] to leave land fallow.”

Leonard, who teaches at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, first came to Chad as a Peace Corps volunteer during the post-civil war reconstruction period in the late 1980s.

“From the time of independence, oil was the promise of the future,” she said. “The lessons the World Bank learned do not inspire confidence that it would be different the next time around. We need a fundamental shift in this development model.”

Dana Steinberg is the editor of the Wilson Center’s Centerpoint.

Photo Credit: “Chad-Cameroon Petroleum Pipeline Development Project,” courtesy of the World Bank. -

ASRI’s Integrated Health and Conservation Programming in Borneo

›If you have a fever in the town of Sukadana in Indonesian Borneo, the locals might suggest you go to the ASRI clinic. It’s in a little house whose front yard is crowded with bicycles and motorbikes. In the waiting room, you examine a whiteboard that explains your payment options. ASRI accepts cash. But it looks like you can also pay with labor in the clinic’s organic garden or its reforestation site. If you own a goat, you can bring in its manure and pay with that. You can even pay with durian tree seeds!

Doctoring both humans and the environment is the raison d’etre of Alam Sehat Lestari (“healthy life everlasting” in Bahasa Indonesia, or ASRI for short), an NGO dedicated to the idea that human health is so intertwined with that of the environment that trying to fix one must include trying to fix the other. Located beside Indonesia’s Gunung Palung National Park, ASRI aims to protect the park’s irreplaceable rainforests by offering health care incentives to local people to stop illegal logging. We’re supported by our sister NGO in the United States, Health in Harmony.

For both people and the forest, the task is urgent. The island of Borneo was once famously covered by rainforest. But now only half of that canopy exists, and less than one-third will remain by 2020. Beginning in the mid-20th century, loggers, palm-oil plantation companies, and farmers logged, burned, and clear-cut their way through the island. Horrifyingly, much of this destruction has taken place in “protected” areas like national parks. The relentless loss of forest has devastated biodiversity in Borneo and severely reduced habitats for many organisms, including one of humanity’s closest relatives, the orangutan – as of 2005, there were about 55,000 left, a tenth of which live in Gunung Palung. Some experts predict the orangutan will be extinct within a few decades. Despite their protected status, Gunung Palung’s forests are continually threatened by illegal logging for valuable hardwood, poor implementation of management practices, and forest fires, many of which are started to clear land for new uses. Over 50,000 hectares of the 90,000-hectare national park’s forest cover are damaged or gone.

Contributing is the fact that Borneo’s economy is based largely on extractive industries; there simply aren’t many other job options. An ASRI survey found that in the Gunung Palung area the average cost of an emergency visit to the district or regional hospital was $460 – more than the average annual income. In fact, one-third of interviewees had faced a choice between health care and food. Financial pressures like that are what drive people to illegal logging. A four-meter board can go for R110,000, or about $10 – a little less than the average villager’s monthly income of $13. Working in a rice field, by contrast, pays about a dollar a day.

Sukadana, located so close to Gunung Palung, is a boom town for these industries. It was recently made a seat of the local regency. We watch new buildings go up every week – most of them built using illegal wood chopped straight out of the national park – and workers and money are flowing in.

As forest is converted to plantations, however, pesticides and fertilizers enter the watershed, which damage water and soil quality as well as human health. Watershed destruction from logging and land conversion leads to flooding which makes it harder to raise rice and can increase rates of flood-related diseases. Logging itself is dangerous work, and there are few or no worker protections. As well, seasonal, man-made forest fires, which this ecosystem is not adapted to and which can last for months, devastate both the natural habitat and respiratory health.

Enter ASRI: Our Sukadana clinic offers high-quality, low-cost medical care to all comers, with discounts for people living in villages that do not contribute to illegal logging (which the National Park office determines using air and ground patrols). This incentive system was devised in consultation with local leaders and is intended to take advantage of powerful social ties in this rural area. But given the complexity of the connections between poverty, health, and the environmental degradation here, ASRI also attacks these problems from other angles.

For one, patients and families can pay by eco-friendly, non-cash means – some of which actually end up providing further benefit to the patients. Many choose to do a stint of labor for ASRI in our organic garden. There they learn techniques that they can apply to their own crops. Some farmers have reported making a considerable profit selling their own organic produce with the skills they learned at ASRI, and some have sworn off traditional slash-and-burn agriculture, because as organic farmers they earn more money for less work. Others decide to work at ASRI’s reforestation site, which aims to restore several hectares of burned-over, degraded grassland to its original forested state. Patients can also bring in compost or manure; rainforest seeds and seedlings; or handmade grass mats, which are snapped up by clinic staff and volunteers.

ASRI’s other programs include Goats for Widows, in which impoverished widows receive a goat and give back its organic manure and one kid. Clinic staff teach townspeople and villagers about the links between the environment and health and include information about diseases like tuberculosis during “movie nights,” when they set up a projection screen and show educational videos. Crucially, ASRI also engages in capacity-building through its trained medical volunteers, who serve as consultants for Indonesian staff doctors who are fresh out of medical school.

On the horizon is a new eco-friendly “super-clinic” that will allow us to perform major surgery and house many more inpatients. We hope that as it goes up, people will learn ways to build with less wood, and that by offering even better health care to people living around the national park, we will gain enough leverage to slow or even stop illegal logging. For the community – everyone from the next generation of Sukadanans to the gibbons and durian trees – that would be a healthy change for all.

Jenny Blair, M.D., is a physician, writer, and long-term volunteer at ASRI, along with her husband, Roberto Cipriano, a LEED-accredited professional and architect who is helping to design ASRI’s newest clinic.

Sources: Center for International Forestry Research, Food and Agriculture Organization, Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program, Mongabay.com, Rainforest Action Network, Tropics, World Rainforest Movement, World Wildlife Foundation

Video and Image Credit: “Conservation – Part 1,” courtesy of AlamSehatLestari, and “Ibu Nurdiah,” used with permission, courtesy of Roberto Cipriano. -

Laurie Mazur at SEJ 2010 on ‘A Pivotal Moment: Population, Justice, and the Environmental Challenge’

› “Right now, half the world’s population – some 3 billion people – are under the age of 25,” began Laurie Mazur on the “Population, Climate, and Consumption” panel at the Society for Environmental Journalists 20th Annual Conference. “It’s the largest generation ever that’s coming of age, and the choices that those young men and women make about childbearing will determine whether world population…grows to anywhere between 8 and 11 billion by the middle of this century.”

“Right now, half the world’s population – some 3 billion people – are under the age of 25,” began Laurie Mazur on the “Population, Climate, and Consumption” panel at the Society for Environmental Journalists 20th Annual Conference. “It’s the largest generation ever that’s coming of age, and the choices that those young men and women make about childbearing will determine whether world population…grows to anywhere between 8 and 11 billion by the middle of this century.”

“The good news is that everything we need to do to slow population growth is something we should be doing anyway,” she continued. Mazur is the author of A Pivotal Moment: Population, Justice, and the Environmental Challenge and director of the Population Justice Project.

She was joined on the panel by Brian O’Neill, who spoke about a new study examining the impact of demographics on carbon emissions, and Jack Liu, who spoke about the impact of household size on emissions in China.

The “Pop Audio” series offers brief clips from ECSP’s conversations with experts around the world, sharing analysis and promoting dialogue on population-related issues. Also available on iTunes. -

Tracking the End Game: Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement

›

The next nine months are critical for Sudan. The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) sets January 9, 2011, as the date when southern Sudanese will vote on secession or unity, and the people of disputed Abeyei will vote on whether to be part of North or South Sudan. Between now and July 2011, when the provisions of the CPA come to an end, we could see the birth of the new country of South Sudan—or a return to a North-South war if the referendum is stalled, botched, or disputed. (Few currently expect that a unity vote will create the “New Sudan” envisioned by the late John Garang.)

-

Ethiopian Case Study Illustrates Shortcomings of “Land Grab” Debate

›The lines have been drawn in the “land grab” debate: Will foreign investors displace small, local land-holders, damaging the environment with exploitive practices? Or will a combination of infrastructure investment and employment opportunities lead to a virtuous development cycle?

Recent reports suggest that the former is more likely than the latter (e.g., see the Oakland Institute, GRAIN, and the Food and Agriculture Organization). In each case, the proposed antidote is the typical wish-list: Boost institutional capacity to ensure that agreements are honored, environmental and labor regulations are observed, and local populations are given a stake in the process.

While it incorporates a broader swath of data and country case studies, the recent World Bank report, “Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can It Yield Sustainable and Equitable Results?” largely recycles this tired diagnosis, as noted recently by Michael Kugelman on The New Security Beat.

But the two months we spent in the Amhara and Oromia regions of Ethiopia, surveying smallholders and profiling large-scale commercial farms, left us with a different impression. After completing 1,200 pages of surveys on smallholder livelihood strategies and farm management practices with 120 local farmers, as well as six profiles of private investors’ farms, we identified several key points that these reports missed.

Strong Laws Don’t Always Scare Investors Away

The World Bank report focuses on the belief that countries with weak institutions attract predatory investors, who use lack of oversight to their advantage by exploiting local populations, abusing regulations, etc. Ethiopia, however, has high institutional capacity relative to other African nations, yet still receives enormous land investment.

Every commercial farm we profiled received yearly visits from multiple regional and federal agencies investigating regulatory compliance. Moreover, two of the farms had been sold to their current owners because the previous business ventures failed to observe the terms of their business proposals. These terms included bringing certain amounts of foreign exchange into the country and hitting export targets.

Ethiopia attracts investors for other reasons. Official documents tout the diversity of its micro-climates, but we suspect investors are more likely drawn by a lease rate roughly 100x lower per hectare than the African average.

Given the emphasis on boosting institutional capacity as a means to ensure positive development outcomes, it’s too bad that the World Bank didn’t choose to conduct one of its case studies on Ethiopian commercial farms. Such a study could provide grounds for discussing what investment governed by stronger institutions would look like.

An Incomplete Paradigm

The potential for population displacement (with or without compensation), job creation, and infrastructure development is a well known and well studied paradigm. The World Bank report investigates the occurrence of these phenomena in its case studies, and the results are unsurprising: Sometimes things go OK and sometimes they go badly. This same story emerges in studies of foreign investments of all stripes: logging, oil and natural gas extraction, precious mineral mining, among others.

A more inventive analysis of land grabs could yield meaningful findings, however. Investors and smallholders are engaged in the same activity — farming — and in the case of cereal farms, they are producing the same crops. The resulting overlap allows for a multitude of creative interactions between smallholders and investors that should receive more attention.

Two of the investors we interviewed used these creative interactions to promote their business plans to regional development authorities. One farm sold certified seed to local farmers; another imported an irrigation system new to the region and plans to introduce it to the broader community. They each rented farm equipment to smallholders and held demonstration days to discuss farming techniques and new crop types with community members. One had already introduced new crops to the adjacent village via an “outgrowing” scheme and was exporting smallholder products from the farm, thus diversifying livelihoods for local farming households.

These are, of course, anecdotal accounts. But they suggest a broader point: More attention must be given to “secondary” benefits like technology and knowledge transfers, outgrowing or renting schemes, and informal interactions. Given the unique attributes of large-scale commercial investment in the agricultural sector, which continues to provide most Ethiopians’ livelihoods, these secondary benefits are the mechanism through which livelihoods seem most likely to be transformed. In this case, the preoccupation with displacement, formal compensation, jobs created, and infrastructure development only leads to generalized and ineffective analysis.

Our smallholder surveys and commercial farm profiles point to one conclusion: The commercial farms in our sample that engaged most fully in those creative interactions will generate substantial benefits for local populations over the next 5-10 years (quantitative analysis to be published in our final report this spring). The particular interactions taking place between these smallholders and commercial farms directly alleviate the primary constraints to smallholder livelihoods identified by our survey, such as lack of mechanization, lack of access to inputs, and inability to generate cash through sale of crops.

It’s far from clear that the World Bank analysis would have captured this reality in Ethiopia given its limited focus. Ideas like outgrowing receive scant attention, and are usually only discussed in hypothetical terms or in parentheticals – a trend the World Bank report unfortunately continued.

Incorporate Case Studies and Put Livelihoods First

So while our limited analysis may not enable us to speak broadly about the effects of commercial farming, we can offer two observations.

First, the creative arrangements that accompany the introduction of commercial farming must be front and center of any study. The study should be grounded in an understanding of the livelihood constraints faced by local populations, followed by an analysis of the types of interactions between commercial farms and smallholders that may affect those constraints, including not only traditional effects, such as displacement and employment, but also atypical impacts, such as improved seed distribution and technology demonstration.

Second, since Ethiopia has enough institutional capacity to be selective when choosing commercial investors (and to ensure they adhere to the terms), it embodies a number of principles the promoted by the World Bank report. Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi views large-scale private farms as one piece of a broader commercialization effort to revolutionize smallholder agriculture, as described in the government’s development plan, PASDEP. This effort is in keeping with the report’s basic recommendation that host governments ensure that investment is compatible with domestic needs.

Understanding the phenomenon of large-scale land acquisitions should be at the top of the international research agenda. The effects on livelihood security and food security (in both developed and developing countries), as well as the potential contributions to resource conflicts, place such land deals among the most consequential recent trends in the international arena.

We believe a new framework must be brought to the analysis of land grabs. To effectively implement this framework, important but overlooked cases, such as we found in Ethiopia, should be included in future studies.

Nathan Yaffe and Laura Dismore are students at Carleton College, who just returned from researching commercial farming in Ethiopia. They can be reached at yaffen@carleton.edu and dismorel@carleton.edu.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “P8060261,” courtesy of flickr user Ben Jarman.

Showing posts from category land.