-

Kavita Ramdas: Why Educating Girls Is Not Enough

› “I’m a big proponent of girl’s education. I believe that it’s a very important and a very valuable human rights obligation that all countries should be meeting,” said Kavita Ramdas, executive director for programs on social entrepreneurship at Stanford University, at the Wilson Center. However, “in the past seven to eight years we have found ourselves in a situation where there’s kind of an enchantment with girl’s education, as though it were the new microenterprise magic bullet to solve everything from poverty, to malnourishment, to inequality.”

“I’m a big proponent of girl’s education. I believe that it’s a very important and a very valuable human rights obligation that all countries should be meeting,” said Kavita Ramdas, executive director for programs on social entrepreneurship at Stanford University, at the Wilson Center. However, “in the past seven to eight years we have found ourselves in a situation where there’s kind of an enchantment with girl’s education, as though it were the new microenterprise magic bullet to solve everything from poverty, to malnourishment, to inequality.”

“The outcomes that we ascribe to girl’s education…are not anything that I would argue with,” she said, yet, this enchantment “has happened simultaneously with a significant drop in both funding and support for strategies that give girls and women access to reproductive health and choices, particularly family planning.”

This is a problem, said Ramdas, because we cannot rely on education alone to do all the heavy lifting required to empower women.

“I think it’s important for us to recognize that there are societies where girls and women have achieved significantly high levels of education in which gender inequality remains,” she said, “for example, places like Japan and Saudi Arabia, where you have high per capita income, high levels of education, and yet…where women and girls are still marginalized and on the edges in terms of decision making.”

“I don’t think we have to wait for one to be able to do the other,” she said. “As we support programs for girls’ education, we also need to demand that those programs be buttressed by strong programs in adolescent health, strong programs in sex education, strong programs that actually provide girls and women with access to family planning and contraception.” -

Women’s Health: Key to Climate Adaptation Strategies

›

The discussion about family planning and reproductive rights “needs to be in a place where we can talk thoughtfully about the fact that yes, more people on this planet – and we’ve just crossed seven billion – does actually put pressure on the planet. And no, it is not just black women or brown women or Chinese women who create that problem,” said Kavita Ramdas, executive director for programs on social entrepreneurship at Stanford University. [Video Below]

-

International Research Institute for Climate and Society

Ethiopia Provides Model for Improving Climate, Other Data Services in Africa

›The original version of this article appeared on the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI).

In developed countries, we are accustomed to having access to long and detailed records on weather and climate conditions, demographics, disease incidence, and many other types of data. Decisionmakers use this information for a variety of societal benefits: they spot trends, fine-tune public health systems, and optimize crop yields, for example. Researchers use it to test hypotheses, make forecasts, and tweak projections from computer models. What’s more, much of these data are just a mouse click away, for anyone to access for free (see examples for climate and health).

Across much of Africa, however, it’s a different story. By most measures, Africa is the most “data poor” region in the world. Wars and revolutions, natural and manmade disasters, extreme poverty, and unmaintained infrastructure, have left massive gaps in socioeconomic and environmental data sets. Reliable records of temperature, rainfall, and other climate variables are scarce or nonexistent. If they do exist, they’re usually deemed as proprietary and users must pay to get access. This is not an inconsequential matter. Without readily available, reliable data, policy makers’ ability to make smart, well-informed decisions is hobbled.

The problem of data access persisted even in Ethiopia, regarded as having one of the better meteorological services on the continent. Thanks to the recent efforts of Tufa Dinku, a climate scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, the situation has improved considerably.

Continue reading on IRI.

Video Credit: Overview of Ethiopia Climate Maprooms, courtesy of IRI. -

Reaching Out to Environmentalists About Population Growth and Family Planning

›“Promoting women’s empowerment is an effective strategy for looking at climate and the environment but also is important in its own right,” said the Sierra Club’s Kim Lovell at the Wilson Center on February 22. “Increasing access to family planning for women around the world is a climate adaptation and climate mitigation solution.” [Video Below] Drawing on research by Brian O’Neill (National Center for Atmospheric Research) and others Lovell explained that meeting the unmet need for family planning around the world could provide up to 16 to 29 percent of the emissions reductions required by 2050 in order to avoid more than two degrees of warming (the target set by nations to prevent the most damaging effects of climate change).

Drawing on research by Brian O’Neill (National Center for Atmospheric Research) and others Lovell explained that meeting the unmet need for family planning around the world could provide up to 16 to 29 percent of the emissions reductions required by 2050 in order to avoid more than two degrees of warming (the target set by nations to prevent the most damaging effects of climate change).

For environmentalists and those concerned with climate change, “sometimes the idea has been that population is toxic, that we can’t talk about population growth,” said Nancy Belden of Belden Russonello and Stewart Consulting, but the results of a recent survey and several focus groups conducted in association with Americans for UNFPA demonstrate that there is great potential for engaging the environmental community in such a discussion.

Belden and Lovell were joined by Kate Sheppard from Mother Jones to discuss how the population and environment communities can come together in the lead-up to the Rio+20 UN sustainable development conference.

Besides providing a basic health commodity, empowering women through access to family planning also improves adaptation outcomes, said Lovell. “Climate change is already happening and women and families around the world are suffering from the effects of water scarcity [and] of erratic weather patterns,” she said. But “when women have the ability to plan their family size and have more choices about their families and about their reproductive health and rights, that makes it easier to adapt to those climate change effects that are already taking place.”

Resonating With Environmental Priorities

“The people who really care about the environment are generally the same people who care about access to contraception and birth control and family planning…they’re a ready audience to hear about these connections and they’re a ready audience to take action about them,” said Kate Sheppard. Reproductive rights issues are something that people can really connect with, she said; “most women, most men too…understand why it’s an important issue and they’ve understood it in their own life and they have [a] very strong response to it.”

When we approach the linkages between environment and population, said Sheppard, it is important to recognize the role of empowering language – language about access to services, education, and resources for women.

The aim of the Americans for UNFPA survey was to find out whether environmentalists can be engaged in discussions of population issues such as family planning and international voluntary contraception, and if so, how?

The results show that “environmentalists are ready to talk about population, they’re ready to listen – it’s not toxic,” said Belden. She outlined three key findings:

First, environmentalists prioritize the environment but they also give a high priority to empowering women, said Belden. “Population pressures are seen as an environmental problem…they don’t dismiss it,” yet the “strongest framework that we could come up with…for engaging people on the issues around voluntary family planning and contraception focuses on women.”

Second, the environmental community is relatively optimistic about the potential outcomes of family planning programs and of foreign aid in general. When queried, half of the environmentalists strongly supported the idea of U.S. contributions to UN programs that provide voluntary access to contraception in developing countries, said Belden.

When asked to mark their top priority among a list of possible outcomes of providing voluntary access to contraception, 47 percent of the environmentalists selected either “improving living conditions for women and their families” or “ensuring women have options and can make reproductive decisions” as their top priority. While a significant number are also concerned about stalling population growth, this integrative focus on improving the lives of women and their families is heartening, said Belden.

In the Run-Up to Rio+20, More Than Pop

One point that all three speakers stressed is the need to integrate consumption into the integrated population message. In her survey work, Belden found that “if you don’t talk about consumption in the same breath, [environmentalists] start wanting to put it in there because otherwise…this is someone blaming others.”

Lovell similarly highlighted that “if we’re working to ensure a sustainable planet for future generations to come, we have to think about consumption and population.” For instance, “the United States makes up five percent of the world’s population but consumes 25 percent of the world’s resources,” she said.

Said Sheppard: “It’s not simply a problem that the numbers of people here on the Earth are going up, it’s a problem of how people, especially here in the U.S., live.”

It is imperative – especially from a sustainable development standpoint – that while working towards integrating environment and population we remain focused on a message that includes “using less but still having a high quality of life” here at home, said Sheppard.

Event ResourcesSources: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Photo Credit: “Timorese Traditional Home,” courtesy of United Nations Photo. -

Elizabeth Grossman, Yale Environment 360

How a Gold Mining Boom Is Killing Children in Nigeria

›March 5, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Elizabeth Grossman, appeared on Yale Environment 360.

In early 2010, while working in the impoverished rural region of Zamfara in northwestern Nigeria, the group Médecins Sans Frontières – Doctors Without Borders – encountered many young children suffering from fevers, seizures, and convulsions. An unusually high number of very young children, many under age five, were dying, and there were many fresh graves.

The doctors initially suspected malaria, meningitis, or typhoid, all common in the region. But when the sick children didn’t respond to anti-malarial drugs or other antibiotics, one of the physicians began to wonder if local mining activity might be implicated. Historically an agricultural area, Zamfara had been experiencing a small-scale gold rush, thanks to rapidly rising gold prices that encouraged the pursuit of even the most marginal sources of ore. Mining work was taking place in and around the villages and within many of the mud-walled compounds where families were using flour mills to pulverize lead-laden rocks to extract gold.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) doctors sent children’s blood samples for testing and the results revealed acute lead poisoning. Many of the children had blood lead levels dozens, even hundreds, of times higher than international safety standards. Within a week, an emergency medical and environmental remediation team arrived and began to grapple with an epidemic of childhood lead poisoning that is being called unprecedented in modern times. In the past two years, more than 400 children have died in Zamfara, more than 2,000 have been treated with chelation therapy, and thousands more have been – and continue to be – severely poisoned by exposure to pervasive lead dust.

Continue reading on Yale Environment 360.

Photo Credit: “Conflict minerals 1,” courtesy of the ENOUGH Project/Sasha Lezhnev. -

USAID’s New Climate Strategy Outlines Adaptation, Mitigation Priorities, Places Heavy Emphasis on Integration

›February 29, 2012 // By Kathleen MogelgaardIn January, the U.S. Agency for International Development released its long-awaited climate change strategy. Climate Change & Development: Clean Resilient Growth provides a blueprint for addressing climate change through development assistance programs and operations. In addition to objectives around mitigation and adaptation, the strategy also outlines a third objective: improving overall operational integration.

The five-year strategy has a clear, succinct goal: “to enable countries to accelerate their transition to climate-resilient low emission sustainable economic development.” Developed by a USAID task force with input from multiple U.S. agencies and NGOs, the document paints a picture of the threats climate change poses for development – calling it “among the greatest global challenges of our generation” – and commits the agency to addressing both the causes of climate change and the impacts it will have on communities in countries around the world.

These statements are noteworthy in a fiscal climate that has put development assistance under renewed scrutiny and in a political environment where progress on climate change legislation seems unlikely.

Not Just Challenges, But Opportunities

To make the case for prioritizing action on climate change, the strategy cites climate change’s likely impact on agricultural productivity and fisheries, which will threaten USAID’s food security goals. It also illustrates the ways in which climate change could exacerbate humanitarian crises and notes work done by the U.S. military and intelligence community in identifying climate change as a “threat multiplier” (or “accelerant of instability” as the Quadrennial Defense Review puts it) with implications for national security.

Targeted efforts to address climate change, though, could consolidate development gains and result in technology “leap-frogging” that will support broader development goals. And, noting that aggregate emissions from developing countries are now larger than those from developed countries, the strategy asserts that assisting the development and deployment of clean technologies “greatly expands opportunities to export U.S. technology and creates ‘green jobs.’”

In addition to providing a rationale for action, the strategy provides new insights on how USAID will prioritize its efforts on climate change mitigation and adaptation. It provides a clear directive for the integration of climate change into the agency’s broader development work in areas such as food security, good governance, and global health– a strong and encouraging signal for those interested in cross-sectoral planning and programs.

Priorities Outlined, Tough Choices Ahead

President Obama’s Global Climate Change Initiative, revealed in 2010, focuses efforts around three pillars: clean energy, sustainable landscapes, and adaptation. USAID’s climate strategy fleshes out these three areas, identifying “intermediate results” and indicators of success – such as the development of Low Emission Development Strategies in 20 partner countries, greenhouse gas sequestration through improved ecosystem management, and increasing the number of institutions capable of adaptation planning and response.

In laying out ambitious objectives, however, the authors of the strategy acknowledge constrained fiscal realities. The strategy stops short of identifying an ideal budget to support the activities it describes, though it does refer to the U.S. pledge to join other developed countries in providing $30 billion in “fast start financing” in the period of 2010 to 2012 and, for those USAID country missions that will be receiving adaptation and mitigation funding, establishes “floors” of $3 million and $5 million, respectively.

The final section of the strategy lists over thirty countries and regions that have already been prioritized for programs, including Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Malawi, and Peru. But “we are unable to work in every country at risk from climate change impacts or with the potential for low carbon sustainable growth,” the strategy asserts. An annex includes selection criteria to guide further funding decisions, including emission reduction potential, high exposure to physical climate change impacts, a suitable enabling environment, coordination with other donors, and diplomatic and geographic considerations.

“Integration” Central to Strategy

The concept of integration figures prominently throughout the 27-page document. For those of us working in the large and growing space where the global challenges of climate change, food security, health, livelihoods, and governance overlap, this attention is heartening. While it may sometimes seem simply fashionable to pay lip service to the idea of “breaking out of stovepipes,” the strategy identifies concrete ways to incentivize integration.

“Integration of climate change into USAID’s development portfolio will not happen organically,” the strategy says. “Rather, it requires leadership, knowledge and incentives to encourage agency employees to seek innovative ways to integrate climate change into programs with other goals and to become more flexible in use of funding streams and administrative processes.”

To this end, USAID plans to launch a group of pilot activities. USAID missions must submit pilot program proposals, and selected programs will emphasize integration of top priorities within the agency’s development portfolio (including Feed the Future and the Global Health Initiative). Among other criteria, pilots must demonstrate buy-in from multiple levels of leadership, and will be selected based on their potential to generate integration lessons and tools over the next several years.

This kind of integration – the blending of key priorities from multiple sectors, the value of documented lessons and tools, the important role of champions in fostering an enabling environment – mirrors work carried out by USAID’s own population, health, and environment (PHE) portfolio. To date, USAID’s PHE programs have not been designed to address climate challenges specifically, and perhaps not surprisingly they aren’t named specifically in the strategy. But those preparing and evaluating integration pilot proposals may gain useful insights on cross-sectoral integration from a closer look at the accumulated knowledge of more than 10 years of PHE experience.

Population Dynamics Recognized, But Opportunities Not Considered

Though not a focus of the strategy, population growth is acknowledged as a stressor – alongside unplanned urbanization, environmental degradation, resource depletion, and poverty – that exacerbates growing challenges in disaster risk reduction and efforts to secure a safe and sufficient water supply.

Research has shown that different global population growth scenarios will have significant implications for emissions growth. New analysis indicates that the fastest growing populations are among the most vulnerable to climate change and that in these areas, there is frequently high unmet need for family planning. And we have also clearly seen that in many parts of the world, women’s health and well-being are increasingly intertwined with the effects of changing climate and access to reproductive health services.

In its limited mention of population as a challenge, however, the strategy misses the chance to identify it also as an opportunity. Addressing the linked challenges of population growth and climate change offers an opportunity to recommit the resources required to assist of the hundreds of millions of women around the world with ongoing unmet need for family planning.

The strategy’s emphasis on integration would seem to be an open door to such opportunities.

Integrated, cross-sectoral collaboration that truly fosters a transition to climate-resilient, low-emission sustainable economic development will acknowledge both the challenge presented by rapid population growth and the opportunities that can emerge from expanding family planning access to women worldwide. But for this to happen, cross-sectoral communication will need to become more commonplace. Demographers and reproductive health specialists will need to engage in dialogues on climate change, and climate specialists will need both opportunities and incentives to listen. USAID’s new climate change integration pilots could provide a new platform for this rare but powerful cross-sectoral action.

Kathleen Mogelgaard is a writer and analyst on population and the environment, and a consultant for the Environmental Change and Security Program.

Sources: FastStartFinance.org, International Energy Agency, Maplecroft, Population Action International, The White House, U.S. Department of Defense, USAID.

Photo Credit: “Displaced Darfuris Farm in Rainy Season,” courtesy of United Nations Photo. -

Afghanistan and Pakistan: Demographic Siblings? [Part Two]

›February 15, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy MadsenLate last year, Afghanistan’s first-ever nationally representative survey of demographic and health issues was published, providing estimates of indicators that had previously been modeled or inferred from smaller samples. My first post on the survey focused on the methodology and results, which found that Afghanistan is not as much of a demographic outlier as many observers had assumed. But perhaps the most surprising finding is how the results compare to those of Afghanistan’s neighbor, Pakistan.

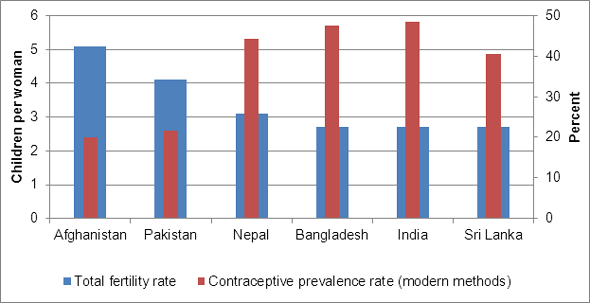

The political future of each country depends largely on the other and, with Afghanistan making progress on reproductive health issues that remain stalled in Pakistan, their demographic trajectories are heading toward closer synchronization as well. In one key measure – use of contraception among married women – Afghanistan is almost identical to Pakistan. The modern contraceptive prevalence rate is 19.9 percent, slightly lower than the rate of 21.7 percent in Pakistan.

While Pakistan faces its own serious political instability, it is widely regarded as more developed than its neighbor. Afghanistan is included in the UN’s grouping of least developed countries, and Pakistan is not. Pakistan’s GDP per capita is almost twice as high. On the surface, this should suggest lower fertility. There is a general negative relationship between economic development and fertility, though demographers are quick to point out its complexities, and David Shapiro and colleagues have found that countries with larger increases in GDP actually experience slower fertility declines.

Pakistan’s fertility rate of 4.1 children per woman is in fact 20 percent lower than Afghanistan’s, but the similarities in contraceptive use, which is one of the direct determinants of fertility, suggest that this gap could be shrinking. If Afghanistan’s median age at marriage (18 compared to 20 in Pakistan) was higher and more women were educated (76 percent of women have never been to school compared to 65 percent in Pakistan), the two fertility rates might be closer.

Pakistan’s Entrenched Challenge

Why are these indicators closer than might be expected? Relative to the other countries in South Asia, Pakistan has had considerably less success in promoting family planning use. Bangladesh has a per capita income about half that of India and one-quarter that of Sri Lanka, yet the three countries’ fertility rates are identical. Nepal has the lowest income in the region – even slightly below Afghanistan – yet more than 40 percent of married women use modern contraception and fertility is three children per woman. And then there is Pakistan. Despite a per capita income 90 percent that of India, only 22 percent of married women use modern contraception and fertility remains persistently high at over four children per woman.

The weaknesses of Pakistan’s family planning program have been well-documented. Government commitment has been lacking and cultural expectations and gender inequities are a powerful force to promote large family size. The country’s most recent DHS report cited disengagement with the program among local agencies, low levels of outreach into communities, and weak health sector support as likely causes for the stagnation of contraceptive use. In summer 2011, the Pakistani government abolished the federal Ministry of Health and empowered provincial governments with all responsibilities for health services. This transfer of authority could pay dividends by increasing local ownership of health care, but some in and outside Pakistan have raised concerns about the loss of regulatory oversight and information sharing entailed in total decentralization.

Compared to the Afghanistan survey, the most recent Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey provides more detail on women’s motivations and preferences regarding fertility and family planning. Overall, 55 percent of married women in Pakistan have a “demand” for family planning; that is, they wish to avoid pregnancy or report that their most recent pregnancy or birth was mistimed or unwanted. More than half of these women are using family planning, while the remaining 25 percent of married women have an “unmet need.”

Unintended pregnancies and births play a major role in shaping Pakistan’s demographic trajectory. The DHS survey finds that 24 percent of births occur earlier than women would like or were not wanted at all. If unwanted births were prevented, Pakistan’s fertility rate would be 3.1 children per woman rather than 4.1. Yet 30 percent of married women are using no contraceptive method and do not intend to in the future. The most common reasons for not intending to use family planning are that fertility is “up to God” and that the woman or her husband is opposed to it.

Linked Destinies

Just as Afghanistan and Pakistan’s political circumstances have become more entwined, their demographic paths are more closely in parallel than we might have expected. For Afghanistan, given the myriad challenges in the socioeconomic, political, cultural, and geographic environments, this is good news; for Pakistan, where efforts to meet family planning needs have fallen short of capacity, it is not. While Afghanistan is doing better than expected, Pakistan should be doing better.

Regardless, both countries are at an important juncture. With very young age structures and the attendant pressures on employment and government stability, each government must reduce unmet need for family planning or face mounting difficulties to providing for their populations in the future. In addition to rolling out health services, turning the share of women without education from a majority into zero would be an excellent way to start.

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and senior technical advisor at Futures Group.

Sources: Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health, Bongaarts (2008, 1978), Cincotta (2009), Embassy of Afghanistan, Haub (2009), International Monetary Fund, MEASURE DHS, Nishtar (2011), Population Action International, Savedoff (2011), Shapiro et al. (2011), UN-OHRLLS, UN Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau, The Washington Post.

Image Credit: Chart arranged by Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, data from MEASURE DHS. -

Afghanistan’s First Demographic and Health Survey Reveals Surprises [Part One]

›February 14, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy Madsen

Late last year, Afghanistan’s first-ever nationally representative survey of demographic and health issues was published, providing estimates of indicators that had previously been modeled or inferred from smaller samples. It shows that Afghan women have an average of five children each, lower than most experts had anticipated, and that their rate of modern contraceptive use is just slightly lower than that of women in neighboring Pakistan.

Showing posts from category global health.