Showing posts from category global health.

-

After the Disaster: Rebuilding Communities

›Recent history has shown that no country, developed or developing, is immune to the effects of a natural disaster. The catastrophic tsunami that struck Indonesia in 2004, the earthquake and subsequent tsunami that struck Japan in 2011, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and Hurricane Katrina in the United States in 2005, are all reminders of the deep and long-lasting impacts that disasters can have from the local neighborhood all the way up to the national level. Each of these disasters also garnered international attention and response, showing that globalization is a game-changer in the worldwide response to community or regional-level crises.

And yet, as evidenced by the continued challenges faced by each of the places above, the disaster response community still struggles with how to contribute most effectively to local level recovery. Recognizing this, the Wilson Center’s Comparative Urban Studies Project and Environmental Change and Security Program, and the Fetzer Institute recently brought together an international group of practitioners, policymakers, community leaders, and scholars to identify best practices and policy in disaster response that are based on community engagement. A subsequent publication, After the Disaster: Rebuilding Communities, highlights the complex nature of disaster response and explores ways to overcome the inherent tension between those responding to disasters and the local community.

Voice, Space, Safety, and Time

A key theme that emerged during the workshop was the importance of identifying the strengths of the post-disaster community and building responses based on those. So how can one identify the strengths of a community? In a previous Wilson Center/Fetzer Institute workshop on community resilience, participants emphasized the importance of civil society voice; the creation of space, both physical and political; and the assurance of safety and time.

Not surprisingly, all of these aspects of resilience emerged in the post-disaster response discussion as avenues to access the strengths of a community. Finding and listening to the voices of the community, identifying the physical spaces or “centers of gravity” around which the community operates (often spiritual and cultural activities, or gatherings that bring women together), and providing safe and sustained support for healing, are necessary steps to engage with and meet the needs of communities.

Having a voice means that people “feel that they have some way to participate meaningfully in decisions that are being made about their lives…[that] they have access, points of influence, and conversation,” explained John Paul Lederach, professor of international peacebuilding at the University of Notre Dame.

Key to listening to the voices of the local community is acknowledging them as first responders. “An involvement and control of the relief and rehabilitation process empowers communities,” wrote Arif Hasan, founder and chairperson of the Urban Resource Centre in Karachi, Pakistan. “It improves their relationship with each other, makes it more equitable with state organizations, and highlights aspects of injustice and deprivation that have been invisible.”

Technology is playing a growing role in giving local communities voice and helping relief workers to identify those centers of gravity. “Whether in conflict or even post-conflict reconstruction, technology gives us a possibility of having a collective history but also collective memory,” noted Philip Thigo, a program associate at Social Development Network in Nairobi. “I spoke in a conference where communities were able to map what was important for them and bring it to the public domain: This is who we are and what we are saying, therefore you, the government, have to interact with us within this space. In that sense technology begins to enable communities to say we exist.”

Connecting to Community Points of Power

At the same time, new technology isn’t paramount to connecting with a community, and just having the technology is not sufficient. Leonard Doyle, country spokesperson for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), shared the story of a simple but effective effort to encourage a national conversation in Haiti by enabling “a flow of information between affected communities, humanitarian actors, and local service providers.”

IOM set up more than 140 information booths, complete with suggestion boxes, among the 1,300 camps where more than 1.5 million homeless people were housed after the 2010 earthquake. There was some doubt that the suggestion boxes would attract letters in a country with just a 50 percent literacy rate, but it didn’t take long for the letterboxes to fill up. In just three days, 900 letters were dropped into a booth in one of the poorest communities, Cité Soleil.

“Amid the flotsam of emails and text messages that dominate modern life,” wrote Doyle, “these poignant letters had an authenticity that is hard to ignore….Urgent cases received a quick response; others became part of a ‘crowd-voicing’ effort to listen to those who had been displaced by the earthquake.”

In the end, “the problem is when we NGOs [or other outside bodies] try to create new systems,” observed Thigo. “We do not look at what exists in the community as knowledge. We do not see how to plug our formal thinking into a structure that we may not understand but that we could perhaps simply try to enhance, to provide better services. We think power doesn’t exist in those communities. But there’s a structure of power. It could be leadership that is not necessarily within the formal context that we understand. The fundamental point is: How can we, even during disasters, connect to these points of power?”

Download After the Disaster: Rebuilding Communities from the Wilson Center. -

Reproductive Health an Essential Part of Climate Compatible Development

›April 11, 2012 // By Sandeep BathalaECSP was at London’s 2012 Planet Under Pressure conference following all of the most pertinent population, health, and security events.

At a panel on “climate compatible development” at this year’s Planet Under Pressure global change conference, Population Action International’s Roger-Mark De Souza was the lone voice to speak about demographics. He presented a detailed analysis of population trends, based on collaboration with the Kenya-based African Institute for Development Policy.

“The link between population dynamics and sustainable development is strong and inseparable – as is the link between population dynamics, reproductive health, and gender equality,” said De Souza. These linkages were emphasized by the UN at the International Conference on Population and Development, held in Cairo in 1994, as well as during the original Rio Conference on Environment and Development in 1992.

“Climate compatible development” is a novel development paradigm being developed by the Climate and Development Knowledge Network and defined as “development that minimizes the harm caused by climate impacts, while maximizing the many human development opportunities presented by a low emissions more resilient future.”

The key tenet of this development framework is an emphasis on climate strategies that embrace development goals and integrate opportunities alongside the threats of a changing climate. In this respect, climate compatible development is seen as moving beyond the traditional separation of adaptation, mitigation, and development strategies. It challenges policymakers to consider “triple win” strategies that result in lower emissions, better resilience, and development – simultaneously.

Although developed nations are historically the major contributors of greenhouse gases due to comparatively high levels of consumption, developing countries are the most vulnerable to consequences of climate change. Emerging evidence shows that rapid population growth in developing countries exacerbates this vulnerability and undermines resilience to the effects of climate change, said De Souza. Socioeconomic improvement will also increase the levels of consumption and emissions from developing countries.

“Meeting women and their partners’ needs for family planning can yield the ‘triple win’ strategy envisaged in the climate development framework,” De Souza said. “Meeting unmet family planning needs would help build resilience and strengthen household and community resilience to climate change; slow the growth of greenhouse gases; and enhance development outcomes by improving and expanding health, schooling, and economic opportunities.”

Decision makers engaged in climate change policy planning and implementation at local, national, and international levels should have access to evidence on population trends and their implications on efforts to adapt to climate change as well as the overall development process, De Souza said.

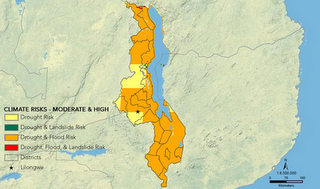

He presented new maps and analysis for Africa, particularly Malawi and Kenya, developed by PAI, building on earlier mapping work which identified 26 global population and climate change hotspots – countries that are experiencing rapid population growth, low resilience to climate change, and high projected declines in agricultural production.

“PAI’s work is a clear demonstration of how better decision making can be informed by the right analysis, in the right format, at the right time,” said Natasha Grist, head of research at the Climate Knowledge and Development Network.

“Most of the hotspot countries have high levels of fertility partly because of the inability of women and their partners to access and use contraception,” said De Souza. He continued:Investing in voluntary health programs that meet family planning needs could, therefore, slow population growth and reduce vulnerability to climate change impacts. This is especially important because women, especially those who live in poverty, are likely to be most affected by the negative effects of climate change and also bear the disproportionate burden of having unplanned children due to lack of contraception.

In conclusion, said De Souza, “global institutions and frameworks that support and promote climate compatible development can enhance the impact of their work by recognizing and incorporating population dynamics and reproductive health in their adaptation and development strategies.”

For full population-related coverage from the conference, see our “Planet 2012 tag.” Pictures from the event are available on our Facebook and Flickr pages, and you can join the conversation on Twitter (#Planet2012).

Sources: Climate and Development Knowledge Network, IPCC, Population Action International.

Photo Credit: Sean Peoples/Wilson Center; Maps: Population Action International. -

Mia Foreman, Behind the Numbers

Serving the Reproductive Health Needs of Urban Communities in Nairobi

›The original version of this article, by Mia Foreman, appeared on the Population Reference Bureau’s Behind the Numbers blog.

Kenya’s population is growing rapidly, more than tripling from 10.9 million people in 1969 to 38.6 million in 2009. According to the United Nations, the annual population growth rate between 2010 and 2015 is 2.7 percent with 22.5 percent of the population residing in urban areas in 2011.

One area that has seen tremendous growth is Nairobi’s largest slum, Kibera. While experts have given estimates ranging from 270,000 to 2,000,000 residents, Kibera is a large area of informal settlements plagued by challenges such as the lack of electricity, job opportunities, and high levels of violence.

While it may be easier to focus on what is lacking in Kibera, there are also many services being provided in the community including affordable and quality reproductive health care by organizations such as Marie Stopes Kenya.

Marie Stopes Kenya was established in Kenya in 1985 as a locally registered nongovernmental organization. It is Kenya’s largest and most specialized sexual reproductive health and family planning organization and is known for providing a wide range of high-quality, affordable, and client-centered services to men, women, and youth throughout Kenya. In 1997, Marie Stopes Kenya opened its first clinic in Kibera and began offering reproductive health services at an affordable rate for residents.

Continue reading on Behind the Numbers.

Sources: UN Population Division.

Photo Credit: “The Kibera ‘river’,” courtesy of Dara Lipton and flickr user The Advocacy Project. -

PBS ‘NewsHour’ and Pulitzer Center Examine Water Shortage and Health Issues in Ghana and Nigeria

› The PBS NewsHour continued its collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting on international reporting last week with an episode on water infrastructure in Ghana and Nigeria. The coverage is especially apropos on World Water Day.

The PBS NewsHour continued its collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting on international reporting last week with an episode on water infrastructure in Ghana and Nigeria. The coverage is especially apropos on World Water Day.

Correspondent Steve Sapienza spoke to reporters in Ghana and Nigeria to highlight long-running access and sanitation issues in both countries caused by poor infrastructure that has not kept up with growth.

Ameto Akpe is a local reporter for Nigeria’s BusinessDay, where her stories “target the contradiction of a country with immense oil wealth and great water resources that are not reaching their citizens.” In the city of Makurdi, capital of the north-central Benue State, she reports on the hundreds of thousands of people who rely on either high-priced water delivery or untreated water drawn straight from the Benue River.

“The previous attempt to build a water treatment plant ended in scandal in 2008,” says Sapienza, “with an unfinished treatment facility and city officials unable to account for $6 million.”

“Unfortunately, the waterworks is only half of the solution to Makurdi’s water problem,” writes Akpe on the Pulitzer Center. “The other half is a system of pipes to deliver the water to the people – and that project is just a twinkle in the eye of a handful of contractors and bureaucrats.”

In Ghana, metro TV reporter Samuel Agyemang explains similar access and sanitation issues in the capitol of Accra and its suburb of Teshie, where some residents have waited decades for piped water, despite substantial foreign investments.

The Pulitzer Center’s Peter Sawyer explains in a companion piece that “the population of Accra has grown enormously in the past several decades. But the water supply system has not grown with it.” As a result, the Ghana Water Company is constantly playing catch-up to provide water to communities, many of whom do not understand how to demand accountability from their officials, says Agyemang.

According to UN estimates, Ghana’s population has increased by more than 10 million people since 1990. Nigeria is one of the fastest growing countries in the world, with 158 million people currently and the UN medium projection estimating a possible 389 million by mid-century.

Reporter Ameto Akpe will be speaking about Nigeria’s water and sanitation problems at an upcoming all-day event on Nigeria at the Wilson Center, scheduled for April 25.

Sources: PBS NewsHour, Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, UN Population Division. -

Hotspots: Population Growth in Areas of High Biodiversity

›More than one-fifth of the world’s population lives in biodiversity hotspots – “areas that are particularly rich in biodiversity and endemic species,” said John Williams of the University of California, Davis, at the Wilson Center on February 29. And those populations are growing faster than the global average. Add to that the fact that “biodiversity continues to decline globally, despite increasing investments in conservation,” said David Lopez-Carr of the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the need for new approaches to conservation becomes evident. [Video Below]

Williams and Lopez-Carr were joined by Dr. Vik Mohan, director of the sexual and reproductive health program for Blue Ventures, a London-based conservation nongovernment organization that works with communities on the remote western coast of Madagascar.

To respond to the demands of the communities and to better protect biodiversity hotspots, the speakers argued that conservation efforts need to incorporate health and livelihood services directed at the growing populations living nearby.

A Complex Relationship

“The relationship between population and biodiversity loss or conservation is a pretty complex relationship,” said Williams.

He offered Latin America and the Caribbean as an example of the multiple factors that can affect how population and biodiversity interact. Population growth in the region has slowed, and agricultural expansion is driving habitat loss as the population ages and urbanizes and as increasing per capita GDP contributes to higher levels of consumption.

In the Indo-Pacific region, stretching from East Asia to Australia, high population growth coupled with economic growth has coincided with an increase in the exploitation of rare species for illegal trade, according to Williams. And in Africa, where the population is growing quickly but without comparable economic growth and amid high levels of instability, subsistence drives ecological exploitation.

Biodiversity and Family Planning in Madagascar

“People who live in the biodiversity hotspots are typically poorer, typically have poorer access to healthcare than their counterparts in the cities or in the world at large, and typically have poorer health than those counterparts,” said Mohan.

Blue Ventures has been working in Madagascar since 2003. The island is one of the most biodiverse areas in the world; 80 percent of its plant and animal life is endemic, meaning it exists there and nowhere else, said Mohan. At the same time, Madagascar is one of sub-Saharan Africa’s fastest growing countries, with a population growth rate of 2.9 percent and an average total fertility rate of 4.6 children per woman.

Blue Ventures initially came to the country to improve conservation in the island’s coastal villages, where residents survive largely on subsistence fishing. But once there, the group quickly found that the population was “growing so rapidly that in spite of our best conservation efforts, the demand for those finite coastal resources [was] outstripping supply,” said Mohan.

“The number of people who are going out to catch fish to feed their to feed their families is going up exponentially, and those fisherman are having to work harder and harder to catch smaller fish that are farther and farther down the food web.”

Realizing that trend, Mohan said that “just by asking a few very basic questions, we unearthed a huge unmet need for healthcare and a huge unmet need for family planning in particular.”

In response, Mohan and his colleagues opened up a family planning clinic in Andavadoaka, one of the villages Blue Ventures serves. On the clinic’s first day, Mohan said, “20 percent of all women of reproductive age came asking for contraception.” Following that opening, they “rapidly found [that] this unmet need was mirrored in every single village along the coast that we worked in,” he said. Since then, modern contraceptive prevalence, initially about seven percent, has increased four-fold, while birth rates have fallen by about one-third. All in all, Mohan said, the population of the Velondriake region, where Blue Ventures operates, is five percent smaller now than it would have been without the group’s family planning services.

Rural Areas Driving Population Growth

Across the developing world, Lopez-Carr said that unmet need for family planning “remains significantly higher” in biodiversity hotspots. Given that high unmet need, especially in Africa, it is easy to infer that “conservation may be less sustainable…if it does not consider health,” he said.

In his ongoing research on population and biodiversity, Lopez-Carr looks at how fertility rates compare in and out of hotspot areas and between regional and local levels. At the country and province level, “high-value conservation areas do not have unusually high total fertility rates (TFRs),” he said. But at more localized levels, “in the most remote rural areas, TFRs remain high, and in many cases, in the most remote rural areas, the demand for family planning is still very low,” indicating that these areas are still in the early stages of their demographic transitions.

The fact that the sub-state picture can look so different from the state-level picture means that there is more work for researchers to do, said Lopez-Carr. “Where the fertility rates are highest is where we have the least data,” he said, and that has significant implications for understanding future population growth.

Looking at UN population projections, the world’s net population gains will be in its poorest cities, he said, but “virtually all this growth is going to be from migration, fueled by remaining high fertility in rural areas.” And “virtually all of that growth will be predicated upon the timing, magnitude, [and] pace of the fertility transition in rural areas.”

Better understanding the demographic picture in rural areas is therefore critical – not just to improving health and preserving biodiversity in the world’s hotspots, but to honing down more accurate global population projections as well.

Event ResourcesPhoto Credit: “Fisherman Carries Day’s Catch,” courtesy of United Nations Photo. -

Food Security in a Climate-Altered Future, Part Two: Population Projections Are Not Destiny

›March 20, 2012 // By Kathleen MogelgaardRead part one, on the food-population-climate vulnerability dynamics of Malawi and other “hotspots,” here.

Too often, discussions about future food security make only a passing reference to population growth. It is frequently framed as an inevitable force, a foregone conclusion – and a single future number is reported as gospel: nine billion people in 2050. But adhering to a single path of future population growth misses the opportunity to think more holistically about food security challenges and solutions. Several recent food security reports illustrate this oft-overlooked issue.

Accounting for Population a Challenge

Oxfam International’s Growing a Better Future: Food Justice in a Resource-Constrained World is a thorough and fascinating examination of failures in our current food system and future challenges related to production, equity, and resilience. It reports newly-commissioned research, carried out by modelers at the Institute of Development Studies, to assess future agricultural productivity and food prices given the anticipated impacts of climate change.

But both the modeling work and the report text utilize a single projection for population growth: the UN’s 2008 medium variant projection of 9.1 billion by 2050 (which has since been revised by the UN up to 9.3 billion). Early on, the report does recognize some degree of uncertainty about this number: “Greater investment in solutions that increase women’s empowerment and security – by improving access to education and health care in particular – will slow population growth and achieve stabilization at a lower level.” But such investments do not appear in the report’s overall recommendations or Oxfam’s food security agenda. This is perhaps a missed opportunity, since the range of possibilities for future population growth is wide: the UN’s low variant for 2050 is 8.1 billion, and the high variant is 10.6 billion.

Food Security, Farming, and Climate Change to 2050: Scenarios, Results, and Policy Options is another frequently-cited report published by the International Food Policy Research Institute in 2010. In recognizing that economic growth and demographic change have important implications for future food security, IFPRI researchers modeled multiple scenarios for the future: an “optimistic” scenario which embodies high GDP growth and low population growth, a “pessimistic” scenario with low GDP growth and high population growth, and a “baseline” scenario which incorporates moderate GDP growth and the UN’s medium population projection. Each of these scenarios was then combined with five different climate change scenarios to better understand a range of possible futures.

Using different socioeconomic scenarios enabled researchers to better understand the significance of socioeconomic variables for future food security outcomes. The first key message from the report is that “broad-based economic development is central to improvements in human well-being, including sustainable food security and resilience to climate change.” This focus on economic development is based in part on the “optimistic scenario,” which counts on high GDP and low population growth (translating to high rates of per capita GDP growth).

Unfortunately, the socioeconomic scenario construction for this analysis doesn’t allow for an independent assessment of the significance of slower population growth, since high population growth is paired only with low GDP and lower population growth is paired only with high GDP. Therefore, none of the report’s recommendations includes reference to reproductive health, women’s empowerment, or other interventions that would contribute directly to a slower population growth path.

Expanding the Conversation to Better Inform Policy

Without a more nuanced treatment of population projections in technical analysis and popular reporting on food security, decision-makers in the realm of food security may not be exposed to the idea that population growth, a factor so critical in many areas where food security is already a challenge, is a phenomenon that is responsive to policy and programmatic interventions – interventions that are based on human rights and connected to well-established and accepted development goals.

There are some positive signs that this conversation is evolving. A new climate change, food security, and population model developed by the Futures Group enables policymakers and program managers to quickly and easily assess the impact of slower population growth on a country’s future food requirements and rates of childhood malnutrition. In the case of Ethiopia, for example, the model demonstrates that by 2050, a slower population growth path would make up for the caloric shortfall that is likely to arise from the impact of climate change on agriculture and would cut in half the number of underweight children.

And recently, we’ve begun to see some of this more nuanced treatment of population, family planning, and food security linkages in a riveting, year-long reporting series (though perhaps unfortunately named), Food for 9 Billion, a collaboration between American Public Media’s Marketplace, Homelands Productions, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and PBS NewsHour.

In January, reporter Sam Eaton highlighted the success of integrated population-health-environment programs in the Philippines, such as those initiated by PATH Foundation Philippines, that are seeing great success in delivering community-based programs that promote food security through a combination of fisheries management and family planning service delivery. Reporting from the Philippines in an in-depth piece for PBS NewsHour, Eaton concluded:So maybe solving the world’s food problem isn’t just about solving the world’s food problem. It’s also about giving women the tools they want, so they can make the decisions they want – here in the world’s poorest places.

Making clear connections of this nature between population issues and the most pressing challenges of our day may be the missing link that will help to mobilize the political will and financial resources to finally fully meet women’s needs for family planning around the world – an effort that, if started today, can have ongoing benefits that will become only more significant over time. Integrating reproductive health services into food security programs and strategies is an important start.

Back in Malawi, just before we turned off the highway to the Lilongwe airport, I asked the taxi driver to pull over in front of a big billboard. We both smiled as we looked at the huge government-sponsored image of a woman embracing an infant. The billboard proclaimed: “No woman should die while giving life. Everyone has a role to play.” Exactly. The reproductive health services that save women’s lives are the same services that can slow population growth and bring food security within closer reach. -

Food Security in a Climate-Altered Future, Part One: “Hotspots” Suggest Food Insecurity More Than a Supply Problem

›March 20, 2012 // By Kathleen MogelgaardSmall talk about the weather with my Malawian taxi driver became serious very quickly. “We no longer know when the rains are coming,” he said as we bumped along the road toward the Lilongwe airport last November. “It is very difficult, because we don’t know when to plant.”

These days, he is grateful for his job driving a taxi. His extended family and friends are among the 85 percent of Malawians employed in agriculture, much of which is small-holder, rain-fed subsistence farming. Weather-related farming challenges contribute to ongoing food insecurity in Malawi, where one in five children is undernourished.

His observations of the recent changes in climate match forecasts for the region: In East Africa, climate change is expected to reduce the productivity of maize – Malawi’s main subsistence crop – by more than 20 percent by 2030, according to a recent analysis by Oxfam International.

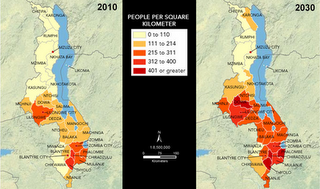

I looked out the window at dusty fields and tried to imagine what Malawi might look like in 2030. For one thing, it will be more crowded. A lot more crowded. According to UN population projections, by 2030, Malawi’s population will have grown from about 15 million today to somewhere between 26.9 and 28.4 million. With climate change dampening agricultural productivity and population growth increasing food demand, how will Malawians – many of whom don’t have enough to eat now – have enough to eat in the future?

It gets quiet in the taxi as the driver and I both ponder this question. Malawi is not alone in being a climate-vulnerable country with a rapidly growing population dependent on rain-fed agriculture. Population Action International’s Mapping Population and Climate Change tool shows us that many “hotspot” countries – scattered across Latin America, Africa, and Asia – face the triple challenge of low climate change resilience, projected decline in agricultural productivity, and rapid population growth.

Agricultural trade, government safety net programs, and foreign assistance will no doubt continue to play an important role in the quest for food security in Malawi and other “hotspot” countries in the future. And climate change adaptation projects will, hopefully, reshape agricultural practices and technologies in ways that can boost yields and enable crops to better withstand temperature and precipitation fluctuations.

These interventions will be critical in addressing the supply side of future food security challenges. But what about growing demand?

Malthus Revisited?

Juxtaposing population growth with food production does, of course, bring us back to Thomas Robert Malthus’ original (and by now somewhat infamous) dire warning: that population growth would eventually outrun food supply. But seeing the scale of the challenges in Malawi firsthand, I must admit that my inner Malthus sat up and took notice.

It is true that technological advances have enabled astounding growth in agricultural yields that have enabled us to feed the world in ways the doom-filled Malthus could never have imagined in the early 19th century. But it is also true that the agricultural productivity gains that helped us keep pace with population growth for so long are beginning to slow: According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, aggregate agricultural yields averaged 2.0 percent growth annually between 1970 and 1990, but that growth in yields declined to 1.1 percent between 1990 and 2007, and is projected to decline to less than 1.0 percent in the years to come.

This comes at a time when the Food and Agriculture Organization reports that food production will need to increase by 70 percent by 2050 in order to adequately feed a larger, wealthier, and more urbanized population.

To dismiss any talk of population growth as outmoded Malthusian hand-wringing misses an opportunity to embrace interventions that can contribute significantly to prospects for future food security – namely, empowering women with information and services that enable them to determine the timing and spacing of their children.

In Malawi and many of the “hotspot” countries around the world, high proportions of women remain disempowered in this regard. Meaningful access to family planning and reproductive health services results in smaller, healthier families that will be better equipped to cope with the food security challenges that are headed their way.

Not only does a smaller family mean that limited household resources go further, but access to family planning and reproductive health services is connected to other important education and economic outcomes.

A new Population Reference Bureau policy brief, for example, highlights how improving women’s reproductive health will not only lead to declining fertility and slower population growth in sub-Saharan Africa, but can also contribute to balancing a woman’s many roles (agricultural producer, worker, mother, caregiver, etc.) in ways that support greater food security for her family. And research by the International Food Policy Research Institute shows that in developing countries, women’s education and per capita food availability are the most important underlying determinants of child malnutrition – with women’s education having the strongest beneficial impact. Access to family planning paves the way for these outcomes – and by slowing population growth, can help to slow the growth in food demand.

Women’s Needs and Future Food Demand

The scale of potential benefits of meeting women’s family planning needs is significant when thinking about future food demand, both globally and especially in food insecure, climate-vulnerable countries. As we have seen in Malawi, there is a range of possible future population sizes and that range grows even wider when the projections are extended to 2050: According to the UN, Malawi’s 15 million today will grow to somewhere between 45 million and 55 million by 2050.

That span of 10 million people embodies assumptions about declining fertility in Malawi. To reach 55 million, the average number of children per woman would need to drop from 5.7 today to 4.5 by 2050. If fertility drops further, to 3.5 children per woman, Malawi’s population would grow to (only) 45 million. Where Malawi ends up in that 10-million-person population spread will have deep implications for per capita food availability, not to mention other important development outcomes.

Fertility declines of this kind do not require coercion or “population control.” As we have seen time and again, when women are empowered with information and services that enable them to determine the timing and spacing of their children, smaller, healthier families are the inevitable result.

Meeting women’s needs for reproductive health and family planning services is not – and never should be – about reducing population size. Universal access to reproductive health is recognized as a basic human right and central development goal (embodied in Millennium Development Goal 5) because of its vital connections to women’s and children’s health, education and employment opportunities, and poverty alleviation. And yet, too many women remain without the ability to effectively plan their families. In Malawi, one in four married women would like to delay their next birth or end child-bearing all together but aren’t using contraception; globally, 215 million have this unmet need.

As global efforts ramp up to address interlinked challenges of food security and climate change adaptation, assessing the role of population growth is more important than ever. And in designing strategies to address these challenges – strategies like the U.S. Government’s Feed the Future Initiative and UN-supported National Adaptation Plans – we should not pass over opportunities to incorporate interventions to close the remaining gap in universal access to family planning, especially in places like Malawi and other “hotspot” countries (such as Haiti, Nigeria, and Nepal), where women’s unmet family planning needs are high and population growth is rapid.

Continue reading with part two on the often under-examined role of population projections in food security assessments here.

Sources: Food and Agriculture Organization, Guttmacher Institute, International Food Policy Research Institute, International Institute for Environment and Development, MEASURE DHS, Oxfam International, Population Action International, Population Reference Bureau, The Lancet, U.S. Department of Agriculture, UN Population Division.

Photo Credit: Women in a village near Lake Malawi make cornbread while caring for small children, used with permission courtesy of Jessica Brunacini. -

John Williams: Helping People and Preserving Biodiversity Hotspots

›March 16, 2012 // By Schuyler Null“Both humans and the number of species in the world are not evenly distributed across the globe,” said John Williams of the University of California, Davis, who recently spoke at the Wilson Center about his contribution to Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas. “In particular we find that species diversity is concentrated in what’s called the biodiversity ‘hotspots.’”

Largely in the tropics, Mediterranean climates, and along mountain chains, biodiversity hotspots are “where there’s a real concentration in number of species and also unique species – plants and animals that exist nowhere else on Earth,” he said.

“It’s a very complex relationship between biodiversity and human population, because it’s not necessarily [true] that places of high human population are a threat to biodiversity,” said Williams. Many different factors play a role, “like education, like consumption, like economic development, different cultures – how people interface with the natural world – all these things create nuances as far as what that relationship is between biodiversity and where people live.”

“There are some basic things we can do that are going to be good for human welfare, as well as biodiversity,” he continued. A few are addressing lack of education, especially among girls, in areas of high biodiversity; providing basic health services, including family planning, where rural growth rates are highest; and improving physical access to rural areas to promote economic development.

“We see there’s a direct correlation between each additional year of schooling a girl has and their fertility during their lifetime,” Williams said. “As people climb out of poverty, they also choose to have smaller, healthier families.”