-

Failed States and Foreign Assistance

›August 28, 2007 // By Sean PeoplesA disorganized, inefficient foreign aid structure can wreak havoc on what the current administration refers to as “transformational diplomacy”—the attempt to build and nurture democratically elected governments. In our post-September 11thworld, failed states (also labeled “precarious states” or “weak states”) have garnered increasing attention as targets for transformational diplomacy. For the U.S., ensuring sustainable and well-governed states depends partially on doling out foreign aid as collateral for reliable partnerships. But nations with limited internal capacity and extreme poverty levels teeter on the edge of uncertainty, and inefficient allocation of aid can further destabilize states that are already vulnerable to becoming havens for nefarious activity.

In cooperation with The Fund for Peace, Foreign Policy magazine recently published its Failed State Index 2007, which ranks countries according to their likelihood of political, social and economic failure. Four out of the five poorest-performing countries—Sudan, Somalia, Zimbabwe, and Chad—are located in Africa. This year’s authors included a valuable section highlighting state stability and its connections to environmental sustainability.

Another excellent Failed State Index-related resource is an analysis by Population Action International (PAI), which drew on the Index to demonstrate that the lowest ranked failing states often had young age structures: “51% of countries with a very young age structure are ranked as critical or in danger by the Failed States Index.”

Many critics view integrating and harmonizing the delivery of aid as crucial to bolstering the stability of these vulnerable states. An excellent brief by the Center for Global Development’s Stewart Patrick critiques the U.S. government’s fragmented approach to engaging failed or failing states. Patrick recommends an “integrated approach that goes well beyond impressive military assets to include major investments in critical civilian capabilities.” Without these critical civilian capabilities, democratic institutions and local capacity cannot take root.

Stephen Browne of the International Trade Centre (ITC) in Geneva also addresses aid coordination in “Aid to Fragile States: Do Donors Help or Hinder?,” which examines Burma, Rwanda, and Zambia as case studies. Ratifying the Paris Declaration—a 2005 international agreement promoting the harmonization and alignment of global aid strategies—was an important step, but developed and developing nations still have much to do, according to Browne:There are agreements by a growing number of bilateral agencies to untie their assistance and mingle it more flexibly with that of others. But to be effective, aid needs to move a radical step beyond the adaptation of individual practices by donors to each other. In each instance, there should be complete alignment with the frameworks and management capacities of recipients. However, the principle of country alignment needs to be reaffirmed, especially in the context of recovery and rehabilitation.

U.S. foreign aid is frequently criticized for not being sensitive enough to recipient countries’ specific needs and on-the-ground conditions. Fortunately, the tools and resources to better understand these conditions are available. Judging from our current foreign aid structure, however, we have underutilized these tools and failed to integrate our knowledge and objectives with the realities of these countries. States fail due to numerous cumulative factors, but responsibly allocating foreign aid may help tip the scales toward improving the odds of success for states on the brink of failure.

Photo: Foreign Policy 2007. -

A New Cold War in the Arctic?

›August 23, 2007 // By Rachel WeisshaarAn environmental security threat is heating up in one of the world’s coldest places: the North Pole. Climate change is causing the polar ice caps to melt, making the Arctic’s vast oil and natural gas reserves more easily accessible. But because this area was previously nearly impossible to access, the rights to the territory are in dispute, with the United States, Canada, Russia, Norway, and Denmark all laying claim to it.

Russia recently initiated a flood of diplomatic posturing when it sent two mini-submarines to plant a rust-proof, titanium Russian flag on the Arctic seabed, four kilometers beneath the polar ice cap. Leaders of the other four countries with claims to the area responded with skepticism and dismay. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper also reiterated Canada’s claim to the fabled Northwest Passage (it previously claimed ownership in 1973)—which the U.S. officially views as an international strait. Ownership of the Arctic was also on the agenda at a previously-scheduled meeting of Bush, Harper, and Mexican President Felipe Calderon earlier this week in Quebec.

One reason why this controversy is so fascinating—and has been getting so much attention in the media—is that it is of interest to so many different communities. There are industry players and observers who want to know how these new fuel reserves will affect businesses; students of national security and politics who are intrigued by the delicate symbolic and rhetorical dance that is unfolding; scientists who are curious as to what the five countries’ new geological exploratory missions will discover; and environmentalists who are concerned about the increased climate change (and localized environmental degradation) that extracting and burning the fossil fuels under the Arctic would likely produce.

Technically, the Arctic ownership debate will be resolved by the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, a group of lawyers and geologists who will rely on the 1994 Law of the Sea Treaty to help determine the validity of ownership claims. But because the stakes are so high—in terms of natural resources as well as political prestige—it seems unlikely that compromise and caution will prevail unless the commission sends a strong message that it will not tolerate Cold War-style intimidation or theatrics. -

The Bewildering Web of U.S. Foreign Assistance

›August 20, 2007 // By Sean Peoples The calls for a more effective U.S. foreign assistance framework have been deafening lately. Although official foreign aid has increased substantially over the last five years, its fragmented organization and lack of clear strategic objectives have been coming under greater fire. More than a year after President Bush announced the new position of Director for Foreign Assistance, a move meant to unify and streamline foreign aid, many prominent voices in the development community argue that substantial reform is still needed to effectively alleviate poverty, strengthen security, and increase trade and investment in developing countries. CARE International’s announcement last week that it would forgo $45 million a year in federal financing is a clear indication that our development strategy is plagued by paralysis on all levels. This post attempts to highlight several different scholars’ innovative approaches to reforming U.S. foreign assistance.

The calls for a more effective U.S. foreign assistance framework have been deafening lately. Although official foreign aid has increased substantially over the last five years, its fragmented organization and lack of clear strategic objectives have been coming under greater fire. More than a year after President Bush announced the new position of Director for Foreign Assistance, a move meant to unify and streamline foreign aid, many prominent voices in the development community argue that substantial reform is still needed to effectively alleviate poverty, strengthen security, and increase trade and investment in developing countries. CARE International’s announcement last week that it would forgo $45 million a year in federal financing is a clear indication that our development strategy is plagued by paralysis on all levels. This post attempts to highlight several different scholars’ innovative approaches to reforming U.S. foreign assistance.

Several critics offer a clear set of reforms, including Raj M. Desai and Stewart Patrick. Desai, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, recommends consolidating the numerous aid agencies and departmental programs into one cabinet-level department for international development. Patrick, a research fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD), advocates a complete overhaul of the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act, given the outmoded law’s lack of clarity.Patrick’s colleagues at CGD analyzed the President’s budget and found that “the U.S. continues to devote a relatively small share of its national wealth to alleviate poverty and promote self-sustaining growth in the developing world.” Moreover, according to Lael Brainard, vice president and director of the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution, aid is not usually distributed purely on the basis of need. “In dollar terms America continues to place far greater emphasis on bribing nondemocratic states than on promoting their democratization.”

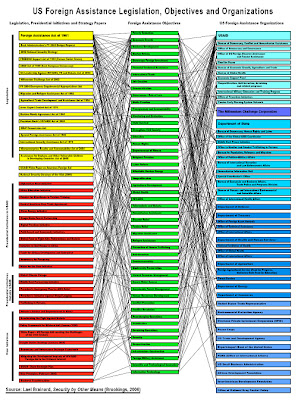

The inefficiency and fragmentation of our current foreign aid structure stems from several cumulative factors, including: numerous competing strategic objectives; conflicting mandates among government and non-governmental organizations; jockeying between the congressional and executive branches for a slice of the pie; and countless organizations overlapping their efforts. Wading through the web of legislation, objectives, and organizations comprising U.S. foreign assistance efforts is a dizzying exercise, as illustrated by the chart above.

Helping us untangle this confusing web is a new book, entitled Security By Other Means: Foreign Assistance, Global Poverty, and American Leadership. The book, edited by Brainard, compiles the findings of the Brookings-CSIS Task Force on Transforming Foreign Assistance in the 21st Century. Not shying away from the nitty-gritty of foreign assistance policy, Security By Other Means delves deep into the current development assistance framework and recommends valuable reforms, which include: integrating strategic security concerns; formulating clear objectives; understanding recipient country capacities; and building effective partnerships that exploit comparative advantages.

Calls for reform have not fallen on deaf ears. Last month, Brookings held a briefing on Capitol Hill discussing foreign aid reform, while the Senate Foreign Relations Committee sponsored a hearing entitled “Foreign Assistance Reform: Successes, Failures, and Next Steps.” The hearing featured testimony from the Acting Administrator for USAID and Acting Director of Foreign Assistance, the Honorable Henrietta H. Fore, as well as three leading experts on foreign assistance: Lael Brainard; Sam Worthington, president and CEO of InterAction; and Steve Radelet, a senior fellow at CGD. Fore committed to “simplifying the process” and integrating the numerous spigots of money flowing outward. However, it was the three NGO experts who presented a more realistic critique and set of recommendations. For these critics, rapid globalization and the inevitable integration of international economies are the impetus for a more unified and harmonized foreign aid structure. A clear consensus emerged from the three experts’ recommendations: promote local capacity and stakeholder ownership; favor long-term sustainability over short-term political goals; and encourage the consolidation and coordination of the disjointed aid structure. While federal aid stagnates, private foundation donations are growing steadily and are poised to overtake official governmental aid. Moreover, private businesses have been steadily expanding the scope of their humanitarian work. Private businesses and foundations have the advantage of being able to avoid much of the bureaucratic red tape involved with governmental aid. Nevertheless, an attempt by business interests, private foundations, and federal foreign assistance to integrate their approaches and build technical capacity could only be a positive step. -

PODCAST – Trade, Aid, and Security

›July 26, 2007 // By Sean PeoplesCurrent approaches to trade and aid often fail to stem poverty, promote stability, or prevent conflict in the developing world. According to Trade, Aid and Security: An agenda for peace and development, existing policies are poorly designed and benefit rich countries, denying developing nations access to vital financial markets. Lifting people out of poverty requires a secure environment and effective trade and aid policies can promote the preconditions for peace and stability. Oli Brown, a project manager and policy researcher at the International Institute for Sustainable Development and one of the editors of Trade, Aid and Security, discusses current development strategies and the conditions for wider political and economic stability.

-

AFRICOM and Environmental Security

›General William E. Ward was recently chosen to lead AFRICOM, the new U.S. military command in Africa currently in its pre-implementation stage. If Ward and AFRICOM are to succeed in promoting peace and stability in Africa, the military must stop viewing security as consisting of conventional, state-to-state relationships and adopt a more flexible “human security” concept. This model views security as “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear,” and includes economic, food, health, personal, community, environmental, and political sub-components. Developing a robust environmental security engagement strategy would be one of the most constructive ways for AFRICOM to implement a human security approach.

The greatest challenge for this nascent command is expanding its tool bag beyond conventional military strategies to include programs that promote the health and security of Africans. Military planners are skilled at determining the number of brigade combat teams, battle carrier groups, and air wings needed for conventional security challenges. But security in Africa depends heavily on non-military factors that fall outside the traditional purview of the armed forces. For AFRICOM to be successful, it must approach security as a mutually beneficial proposition, not a zero-sum game. Most African governments view the Department of Defense’s attempt to adopt a more nuanced approach to security in Africa with guarded optimism. They would certainly welcome environmental partnerships with AFRICOM as a way to promote political and economic stability through sustainable ecological practices, according to discussions held with Amina Salum Ali, the African Union’s ambassador to the U.S.

One of the top security concerns of African leaders—and one that is little-appreciated in U.S. security circles—is the impact of environment on stability and security. The ongoing misery in Darfur, which is partially rooted in conflicts over land and water use, is one tragic example of this link. On a positive note, UN Environment Programme (UNEP) researchers recently discovered water there that may well prove to be a source of resolution. That said, numerous reports—such as the one by the CNA Corporation’s Military Advisory Board—indicate that climate change and environmental catastrophes will continue to be a source of instability in Africa. Unfortunately, the continent most affected by environmental shock is also the least capable of mitigating its effects. AFRICOM must develop an engagement strategy that works with host governments, international membership organizations, NGOs, and other U.S. governmental agencies to find solutions to Africa’s environmental challenges.

The first, and most obvious, advantage of an environmental security strategy is its potential to build nontraditional alliances. Numerous organizations, from UNEP to the World Wildlife Fund, are actively working in Africa in this arena. AFRICOM could benefit significantly from the years of on-the-ground experience that these groups possess. What remains uncertain is the willingness of these civilian organizations to partner with the new command.

A second advantage of an environmental security strategy is that it allows the U.S. military to engage constructively with host governments and regional economic communities. Using AFRICOM to train African militaries on emergency disaster response, for instance, encourages those militaries to work under the mandate of civilian authority and fosters long-term democratic governance.

The idea of environmental security as a military engagement strategy is not new. When General Anthony Zinni was head of Central Command in central Africa, he devoted an entire section to environmental engagement programs, establishing a strong track record of success. Given that environmental concerns are intertwined with a host of other pressing problems in Africa, a coherent environmental security strategy would pay dividends on multiple levels.

Shannon Beebe is a senior Africa analyst at the Department of the Army. The opinions expressed in this article are solely his own and do not reflect the positions of the Department of Defense or the Department of the Army.

-

The “Crime” of Dialogue

›July 19, 2007 // By Geoffrey D. Dabelko My friend and colleague is in jail. Unjustly.

My friend and colleague is in jail. Unjustly.

Her name is Haleh Esfandiari and she is a grandmother. In early May, she was thrust into solitary confinement in Iran’s Evin Prison with a single blanket. She hasn’t been allowed to meet with her friends, family, or lawyers since then. This picture shows Evin Prison nestled within the leafy northern suburbs of Tehran at the foot of snow-capped mountains, but the prison has none of the bucolic qualities that the image suggests. “Notorious” is the ubiquitous descriptor.

Haleh’s “crime” is doing what we do every day here at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.: provide a safe space where scholars, policymakers, and ordinary men and women can learn from one another through open, non-partisan dialogue on today’s most pressing issues. Or at least we thought it was safe.

Haleh’s job is to foster discussion of the many political and social issues at stake in the Middle East, often with a special focus on Iran, one of the two countries she calls home. Haleh is a world-renowned expert on Iran’s rich language, culture, history, and politics. Yet the Iranian Intelligence Ministry has charged her and a handful of other Iranian-Americans with attempting to foment a velvet revolution to overthrow the theocratic regime.

“Nonsense,” says Lee Hamilton, the former congressman who is my and Haleh’s boss at the Wilson Center. As other commentators have pointed out, Haleh is more likely than most in Washington to give those sympathetic to the Ahmadinejad government an opportunity to make their case. She assiduously avoids having financial supporters for her Middle East Program who might compromise her neutrality. She even refuses to go on Voice of America for fear it would associate her with the Bush administration’s strategy of trying to oust regimes rather than change regime behavior.

I serve as a program director at the Wilson Center, just as Haleh does. While her area of expertise is U.S.-Iranian relations, mine is finding ways to use the environment to build trust and confidence between adversaries. Haleh and I have routinely collaborated on environmental and health issues. For instance, in 1999, Haleh and I hosted ten Iranians who headed environmental nongovernmental organizations or were professors of environmental studies. They came to the United States as guests of Search for Common Ground in order to develop new allies in battling environmental challenges in Iran and gain a deeper understanding of Iran’s environmental issues. In both Tehran and Los Angeles, for instance, tall mountains trap pollution over the city, causing poor air quality.

Search also hoped that the Iranian delegation would build civil society links between Iran and the U.S. that could serve as a baby step in a long path to reconciliation between the two countries’ peoples and governments. In this way, environmental dialogue may serve as a “lifeline” for dialogue when a relationship is otherwise stormy. Some of us have called this and similar efforts “environmental peacemaking.”

In May 2005 it was my turn to go to Iran. Whereas Haleh routinely visits Iran because her ailing mother still resides there, it was my first venture. My previous attempts to reciprocate the Iranian delegation’s visit had fallen through because I had been denied a visa. But this time, the Iranian government was doing the inviting. Under the government of President Khatami, “dialogue among civilizations” was a key foreign policy initiative. Massoumeh Ebtekar, Iran’s vice president for environment, partnered with the UN Environment Programme to organize a large international conference entitled “Environment, Peace, and the Dialogue of Civilizations.”

The country’s first female vice president, Madame Ebtekar gained revolutionary street cred as “Mary,” the student spokesperson during the 1979 embassy takeover and hostage crisis. In organizing the conference, she was using environmental issues to engage governments (six ministers of environment attended the conference), UN leaders, and civil society representatives from all over the world. When President Khatami addressed the attendees, it was clear that even the highest levels of the Iranian government supported Ebtekar’s initiative.

Progress made those days in Tehran was hard to measure. For me, the most encouraging signs came not at the conference but on the wide boulevards and tree-lined riverside pathways of Isfahan, where a Norwegian colleague and I ventured as tourists. Looking distinctly non-Iranian, the two of us were repeatedly approached by men, women, and children, who were uniformly welcoming. The short version of each conversation: Don’t you think our country is beautiful? Our governments have their differences, but you shouldn’t mistake those disagreements for Iranian hatred of the American people.

It is this sympathetic view toward Iran that I am sure Haleh wants us to bear in mind as our outrage at her ludicrous detention intensifies. No one has been allowed any in-person contact with her since her May 8th arrest. Monitored minute-long calls to her 93-year-old mother are the only source of information on Haleh’s condition. Naturally, she assures her mother that she is fine, but we have no way of knowing whether or not that is true. And no one is “fine” after being falsely charged with capital crimes and spending more than two months in solitary confinement.

The generous view of Iranians that I gained on my one short trip there is harder and harder to keep in mind. The government changed hands just after I visited in the summer of 2005, and the dramatically more hostile Ahmadinejad regime has jettisoned any efforts toward regular dialogue on even less-contentious issues than nuclear proliferation. President Khatami, Madame Ebtekar, and other government officials seeking dialogue with the West have been sidelined. I am afraid to even email the Iranian colleagues I met during my visit for fear that they would come under suspicion for such an exchange.

Imprisoning Haleh has not done Iran’s government any favors. All the Intelligence Ministry has accomplished by detaining her is silencing one of the most thoughtful, evenhanded voices currently speaking about Iran and the Middle East. Iran’s imprisonment of Haleh is damaging its global image and reducing the international community’s sympathy for its goals. We demand Haleh’s immediate release. It will be to her benefit and to Iran’s.

More information on Haleh’s case is available at http://www.wilsoncenter.org/ and http://www.freehaleh.org./ -

Persian Gulf to the “New Gulf”: New Book Takes New Approach to U.S. Energy Relationships

›May 29, 2007 // By Sean PeoplesAs Americans grow increasingly uneasy with our reliance on oil imports from the Middle East, a new region in Africa—the Gulf of Guinea—is emerging as a pivotal oil exporter. An ambitious new book, Oil and Terrorism in the New Gulf, written by James J. F. Forest and Matthew V. Sousa, focuses on this region of Africa and highlights the U.S. strategic interest in its oil-producing countries: Angola, Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria, and the island nations of Príncipe and São Tomé. This “New Gulf” not only provides the U.S. with a new oil supply, but also affords a chance to reframe our energy relationships.

Oil consumption is on the rise, with the United States leading the pack at nearly 25 percent of aggregate global oil use. Meanwhile, rapid industrialization and economic growth in India and China continues to push demand even higher. The Gulf of Guinea region is vying to meet the demand.

This book asks a critical question: how will the New Gulf cope with growing demand for oil in the face of pervasive poverty, weak governance, and corruption? The crux of the problem: stability in this region is an obstacle. According to the authors, stability is contingent on a calculated foreign policy framework, and the United States’ ability to learn from its mistakes in its quest for Middle East oil:Our continued support for undemocratic regimes, coupled with our willingness to do virtually anything to maintain open and reliable access to the oil resources of the Middle East, has produced increasing animosity throughout the region that will take years of hard work to reverse.

The authors advocate building energy relationships that avoid the Middle East model—a model beset by “shortsighted U.S. interests rather than long-term, fundamental U.S. values.” Instead, they say, America’s energy relationship with the New Gulf should be stable and cooperative, and built off a clear framework that promotes three, integrated priorities:- 1. Human security

- Economic development

- Democratization

-

Saving the World

›What’s wrong with the world today? A whole lot. War in Iraq, poverty in rural America, malaria in Africa, global warming…the list is endless. But the editors of Foreign Policy think they have a way to solve these problems and more. The magazine’s new cover story, “21 Ways to Save the World,” is a collection of short essays on a wide range of global issues by some of the world’s leading thinkers.

Besides the interesting topics and the authors’ engaging styles, I like this series because it forces journalists and scholars—both of whom usually write about problems—to write about solutions. This shift is important because policymakers often get stumped when they hear that issues like high fertility and pollution are concerns of national security—what can they do about these seemingly insurmountable problems?

Most of the dilemmas and solutions presented in the article will be familiar to the informed reader. Amy Myers Jaffe extols the virtues of electricity. Seth Berkeley is optimistic about an AIDS vaccine. Jeffrey Sachs calls for malaria intervention. But some of the proposed solutions will be a tough sell for the policy audience.

For example, as he does elsewhere, Nicholas Eberstadt draws attention to the astonishingly high mortality of Russians—males in particular. He argues that if the United States intervenes, the benefits would be two-fold: humanitarian gains through Russian lives saved, and also political dividends in the form of a strengthened Russian democracy. But increased foreign aid for Russia’s health crisis will likely be a bitter pill for American politicians to swallow for a couple of reasons: First, there are still too many people occupying important government posts who got their first taste of power during the Cold War. For these folks, Russia is still the big bad bear and they may not be too keen on taking action to strengthen the Russian state. And for policymakers who are more humanitarian-minded, Eberstadt’s argument is still a hard sell because there’s simply no room for another needy state. Thanks to relentless campaigning by celebrities like Bono and philanthropists like Bill and Melinda Gates, the U.S. government is finally attempting to gain traction in Africa and see the deplorable conditions there as both a humanitarian and security concern (AFRICOM is the most recent example of the United States trying to get ahead of the problem). Now they have to save Russia, too?

This gets at the larger issue with the collection of essays. While the editors of FP are noble in their aim to tackle all of the world’s troubles, I fear that policymakers will just continue to be overwhelmed by the magnitude of problems and the multitude of solutions—the deer-in-headlights response. Thomas Homer-Dixon is correct when he writes that problems are complex, systems are complex, and solutions must be complex. With so many problems of equal importance—in an environment where everyone has their issue—and so many solutions of equal viability, how are policymakers ever to choose?

Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Government and Politics at the University of Maryland, and a consultant to Policy Planning in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy at the U.S. Department of Defense.

Showing posts from category foreign policy.