-

Book Review: ‘Global Warring: How Environmental, Economic, and Political Crises Will Redraw the World Map’ by Cleo Paskal

›April 9, 2010 // By Rachel Posner As record-breaking snowstorms blanketed Washington, D.C. this winter, I took advantage of the citywide freeze to read Cleo Paskal’s new book, Global Warring: How Environmental, Economic, and Political Crises Will Redraw the World Map. In it, Paskal makes a compelling case for why the West should care about the geopolitical shifts—already underway—that will be exacerbated by climate change.

As record-breaking snowstorms blanketed Washington, D.C. this winter, I took advantage of the citywide freeze to read Cleo Paskal’s new book, Global Warring: How Environmental, Economic, and Political Crises Will Redraw the World Map. In it, Paskal makes a compelling case for why the West should care about the geopolitical shifts—already underway—that will be exacerbated by climate change.

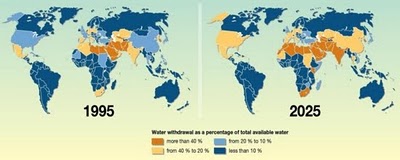

Paskal eloquently explains the science behind climate change in layman’s terms, breaking down incredibly complex issues and drawing connections across seemingly disparate challenges, such as rising food prices, degrading energy infrastructure, and growing water scarcity. She is a skilled storyteller, using memorable vignettes (and at times even humor) to effectively illustrate these climate-related complexities.

But what truly sets Paskal’s book apart from a number of recent works on this topic is her ability to elucidate the major power shifts that are directly related to today’s climate and resource stresses. “Environmental change is the wild card in the current high-stakes game of geopolitics,” she writes (p. 249). Such natural resource stresses will only become more pronounced in the future.

Global Warring highlights a number of key challenges and opportunities that could take the United States and other Western nations by surprise if they don’t change policies now to secure their positions as major global powers.

Impacts of Environmental Change: Like the developing world, the United States and other Western nations will suffer from extreme weather events and the broader effects of environmental change. However, the United States has “institutional, regulatory, political, and social” weaknesses that affect its “ability to absorb the stress of repeated, costly, and traumatic crises,” including its expensive, aging infrastructure, writes Paskal (p. 40). For example, while the country will face more Hurricane Katrinas, the U.S. military is still not adequately prepared to address such domestic environmental disasters.

Transportation Routes and Trade: The Northwest Passage—the sea route that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through North American waterways—is a highly coveted trade route that will become all the more valuable as Arctic ice continues to melt in the years ahead. Already the United States, Canada, Russia, China, and even the European Union are engaged in a geopolitical chess game for control of the Arctic. Each is staking a claim to the natural resources below the surface, new shipping routes, and strategic chokepoints. According to Paskal, if the West wants to remain “a major force in the twenty-first century,” the United States and the EU should help Canada secure its claim to the Northwest Passage. This way, Canada could protect its borders and “talk to other countries, including Russia, on a more equal basis about creating and jointly using facilities like search, rescue, and toll stations, and on methods of speeding legitimate, safe shipping and exploration in the northern waters,” she writes (p. 125).

New Power Dynamics and Partnerships for China, India, and the West: China and India are two of the world’s fastest growing economies and each are taking on new roles in Asia and beyond. But could climate change and environmental challenges stem their growth, or will these “powerhouse” countries prove resilient? As the global power balance begins to shift toward Asia, Paskal sees India as the “swing vote” that might shape the future of geopolitics for the next long while” by aligning itself with Russia and China and potentially marginalizing the West (p. 185). Alternatively, the West could finally acknowledge India as an equal partner—for example, by strengthening civilian nuclear cooperation—and thus help foster stability over the long term. Stresses on natural resources, now and in the future, will only increase the importance of strong alliances and geopolitical partnerships.

Rising Sea Levels in the Pacific Ocean: Most Americans and other Westerners are not terribly concerned about the welfare of the small-island nations in the Pacific whose entire existence is threatened by sea-level rise. Paskal rightfully draws our attention to the ambiguous state of the international law of the sea, which leaves much of this region up for grabs when sea levels rise and coastlines change. “At stake is access to fisheries, sea-lanes in relatively calm waters, control over regional security, unknown underwater resources, geostrategic advantage, and geopolitical political leverage,” she writes (p. 214). China has already gone to great lengths to secure its control over the Pacific, and if it continues to be successful, the United States will risk losing influence in the region.

Throughout all of these cases, Paskal weaves in a discussion of the growing and strategically significant practice of “nationalistic capitalism.” For example, she describes how China’s state-owned companies work with their government to “advance national strategic interests,” often signing bilateral deals that “cut out the open market and overtly link much-needed resources to wide-ranging agreements on other goods and services, including military equipment” (p. 94-5). As China and other nationalistic capitalist countries expand their reach into the resource-rich regions of Africa and Latin America, fewer resources (like food and fuel) will be available in the open market. For the United States and other “free market” nations, this practice could lead to higher prices and increased competition for business and political alliances.

Overall, Global Warring is an excellent read that I would recommend to friends and colleagues, especially those tracking long-range global trends and promoting farsighted policies. I appreciated Paskal’s recurring call for abandoning short-term expediency in U.S. decision-making in favor of a longer-term approach. Paskal shows how over time the United States’ short-term interests are creating major vulnerabilities that will be worsened by environmental stresses in the future.

The book’s only notable shortcoming is its skewed geographic scope. Paskal focuses heavily on North America and Asia, particularly China and India, and only briefly mentions Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Australia. Obviously, a book about the shift of major world powers would concentrate on the most influential players, but these other regions are worthy of greater consideration given their critical natural resources, demographic trends, and ongoing climate adaptation efforts.

Regardless of how the climate changes, the environmental trends described in Global Warring are already manifesting as geopolitical realities that will dramatically affect the United States. As Paskal says, “Countries that want internal stability, influence over allies, control over sea-lanes, and access to critically important resources better start planning now (p. 235).

Rachel Posner is a fellow in the Energy and National Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Previously, she has served as the assistant director of the CSIS Global Water Futures Project; research associate with the CSIS Global Strategy Institute; and Brent Scowcroft Award Fellow with the Aspen Strategy Group. -

Canada Flip-Flops on Family Planning, Will the G-8 Follow?

›April 5, 2010 // By Laura Pedro “The Canadian government should refrain from advancing the failed right-wing ideologies previously imposed by the George W. Bush administration in the United States, which made humanitarian assistance conditional upon a ‘global gag rule’ that required all non-governmental organizations receiving federal funding to refrain from promoting medically-sound family planning,” said the Canadian Liberal Party about the country’s Conservative government in a Parliamentary motion last week.

“The Canadian government should refrain from advancing the failed right-wing ideologies previously imposed by the George W. Bush administration in the United States, which made humanitarian assistance conditional upon a ‘global gag rule’ that required all non-governmental organizations receiving federal funding to refrain from promoting medically-sound family planning,” said the Canadian Liberal Party about the country’s Conservative government in a Parliamentary motion last week.

Though Prime Minister Stephen Harper had pledged to include a voluntary family planning initiative in Canada’s foreign aid plan at last year’s G8 meeting in Italy, the Conservative government recently said that the initiative will not be part of its G8 plan at the upcoming meeting in Canada this June.

This move has surprised both Canadians and Americans. U.S. President Obama overturned the Mexico City policy last year, and has fully supported the inclusion of family planning methods as part of foreign aid.

Harper’s government has maintained that maternal and child health services, such as vaccinations and nutrition, will be a priority, but various components of family planning, including birth control and abortion, will not be included in the Canadian initiative.

The Tories, as along with three Liberal MPs, voted down the Liberal motion 138-144, which requested clarification of Harper’s maternal health initiative and pushed for the inclusion of the full range of family planning options. The Tories focused solely on what they called “anti-American rhetoric” in the motion, which drew attention away from the divisive issue of abortion.

The issue has got caught up in domestic Canadian politics, with opposition Liberals trying to equate the Conservatives with the George W. Bush administration and the Conservatives trying to avoid discussion of intra-party debates on the contentious issue of abortion.

Now it seems likely like that Harper will go to the G8 summit in Ontario with a foreign aid plan for maternal health that makes no reference to issues of contraception. According to Canada’s International Co-operation Minister Bev Oda, “saving lives” of women and children is a higher priority than family planning.

But most international maternal health advocates don’t agree. “Maternal mortality rates are high among women who do not have access to family planning services. Contraception can reduce the number of unplanned pregnancies,” said Calyn Ostrowski, program associate for the Wilson Center’s Global Health Initiative. “For example, at a recent event on our Maternal Health series, Harriet Birugni of the Population Council in Kenya described how integrating reproductive health services such as family planning can reduce maternal mortality rates, particularly for poor young women who have the least access to contraception.”

In response to Canada’s announcement, U.S. Secretary of State Hilary Clinton said that the United States will be promoting global health funding, including access to contraception and abortion, at the G8. “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health,” she said during a news conference with other G8 ministers. Britain has also agreed with this position, which has led Canadian Liberal Party Leader Michael Ignatieff to say that Canada’s G8 position goes against the international consensus.

Laura Pedro is the program assistant for the Canada Institute, and a graduate of the University of Vermont.

Photo.: Prime Minister Stephen Harper, courtesy Flickr user Kashmera -

Tapping In: ‘Secretary Clinton on World Water Day’

›March 23, 2010 // By Julien Katchinoff “It’s not every day you find an issue where effective diplomacy and development will allow you to save millions of lives, feed the hungry, empower women, advance our national security interests, protect the environment, and demonstrate to billions of people that the United States cares. Water is that issue,” declared Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at a World Water Day event hosted by the National Geographic Society and Water Advocates.

“It’s not every day you find an issue where effective diplomacy and development will allow you to save millions of lives, feed the hungry, empower women, advance our national security interests, protect the environment, and demonstrate to billions of people that the United States cares. Water is that issue,” declared Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at a World Water Day event hosted by the National Geographic Society and Water Advocates.Alongside speeches by representatives from government and the non-profit sector, Secretary Clinton repeatedly emphasized America’s support for water issues. “As we face this challenge, one thing that will endure is the United States’ commitment to water issues,” she asserted. “We’re in this for the long haul.” Beyond simply highlighting the importance of the issue, Secretary Clinton also affirmed commitment to new programmatic, cross-cutting initiatives that will target water as a keystone for development and peace.

ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko, who attended the event, noted that Secretary Clinton’s speech ran counter to the much publicized notion that water scarcity is an unavoidable catalyst for conflict.

She came down squarely on the side of inclusion by identifying water as both a ‘human security’ and ‘national security’ issue. At the same time, she did not fall prey to the common pitfall of arm-waving about water wars. She flagged conflict and stability concerns, but also raised solutions through meeting needs associated with water and development. She went out of her way to emphasize water’s potential for peace and confidence-building, reflecting a commitment to capturing opportunities rather than merely identifying threats.

Secretary Clinton highlighted five crucial areas that comprise the United States’ whole-of-government approach to water issues:

1. Building capacity:

Through efforts with international partners, the United States hopes to strengthen the abilities of water-stressed nations to manage vital water resources. Agencies such as the Millennium Challenge Corporation and USAID are implementing initiatives that will enhance national ministries and encourage regional management cooperatives.2. Elevating diplomatic efforts:

A lack of coordination between the numerous UN agencies, governments, and multilateral funding organizations hinders global water progress. By bringing this work together, the United States can act as a leader, demonstrating a positive diplomatic precedent for fragile and water-stressed nations.3. Mobilizing financial support:

Relatively small grants have achieved large impacts. Work by the United States to strengthen capital markets in the water sector shows that it is possible to earn large returns on water investments. Successful examples range from educational and awareness-building programs, to desalinization and wastewater treatment plants.4. Harnessing the power of science and technology:

Although there is no silver technological bullet to solve the global water crisis, simple solutions, such as ceramic filters and chlorine disinfection systems, do help. Additionally, sharing government-accumulated technological knowledge can have significant impacts, as demonstrated in a recent NASA-USAID project establishing an Earth-observation monitoring and visualization system in the Himalayas.5. Broadening the scope of global partnerships:

By encouraging partnerships and elevating water in its global partnership initiatives with NGOs, non-profits, and the private sector—all of which are increasingly engaged in water issues—the Department of State hopes to maximize the effectiveness of its efforts.The holistic approach advocated by Secretary Clinton reflects a distinct evolution of American diplomacy within this area, which is strongly supported by the water community. “The policy directions outlined in the speech, the five streams, represent a victory for those in and outside of government who have argued for a broad, rather than narrow, view of water’s dimensions,” said Dabelko. “The diversified strategy focuses on long-term and sustainable interventions that respond to immediate needs in ways most likely to make a lasting difference.”

In her concluding remarks, Secretary Clinton sounded a positive note, noting that for all of the press and attention devoted to the dangers of the global water crisis and the possible dark and violent future, dire predictions may be avoided through a smart, coordinated approach. “I’m convinced that if we empower communities and countries to meet their own challenges, expand our diplomatic efforts, make sound investments, foster innovation, and build effective partnerships, we can make real progress together, and seize this historic opportunity.”

Photo Credits: State Department Official Portrait; UNEP.

-

Video—Ken Conca: ‘Green Planet Blues: Four Decades of Global Environmental Politics’

›February 19, 2010 // By Julia Griffin“Much of the conversation about the global environment, frankly, is an elite conversation,” says Ken Conca, professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland. “But at the same time there are community-level voices, there are voices of indigenous people, there are voices of the powerless, as well as the powerful…. I think it’s important to capture them and not just limit [the conversation] to the most easily accessible voices.”

Conca and co-editor Geoff Dabelko include these oft-muted voices in the newly released 4th edition of Green Planet Blues: Four Decades of Global Environmental Politics. “One of the things we were really trying to achieve was to give people a sense of the history,” said Conca. To fully understand the origins of today’s debates, students must go back to the beginning of the last four decades of international environmental politics.

Three key paradigms—sustainability, environmental security, and ecological justice—frame the debates in Green Planet Blues. “Ideas do matter,” says Conca. “They really do change the world, and one of the premises of our work and of the book is to try to understand what sorts of ideas people bring to the table when they think of global environmental problems.” -

Climate Combat? Security Impacts of Climate Change Discussed in Copenhagen

› Leaders from the African Union,the European Union, NATO, and the United Nations have agreed unanimously that climate change threatens international peace and security, and urged that the time for action is now.

Leaders from the African Union,the European Union, NATO, and the United Nations have agreed unanimously that climate change threatens international peace and security, and urged that the time for action is now.

In Copenhagen Tuesday, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary-general of NATO; Jean Ping, the chairperson of the Commission of the African Union; and Helen Clark, the administrator of the UN Development Programme, were joined by Carl Bildt and Per Stig Møller, foreign ministers of Sweden and Denmark respectively, to take part in a remarkable public panel discussion organized by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The leaders agreed climate change could hold serious implications for international security, both as a “threat multiplier” of existing problems and as the cause of conflict, under certain conditions.

Møller suggested there is evidence that higher temperatures in Africa could be directly linked to increases in conflict. Ping emphasized that African emissions make up only 3.8 per cent of the climate problem, though Africa will likely suffer some of its most serious impacts. Fogh Rasmussen warned of the dangers of territorial disputes over the Arctic as the sea ice recedes. “We need to stop the worst from happening,” said Clark.

While there was broad agreement on the seriousness of the challenge, the participants differed on what should be done. Responding to a question from the audience, Bildt argued that Europe should not necessarily throw open its doors to climate migrants, but that the bloc needed to help countries deal with climate change so people can stay at home. Clark argued that enlightened migration policy could meet two sets of needs: reversing declining populations in the North while providing a destination for unemployed workers from the South.

Fogh Rasmussen said militaries can do much to reduce their use of fossil fuels. He noted that 170 casualties in Afghanistan in 2009 have been associated with the delivery of fuel. There is no contradiction, he argued, between military efficiency and energy efficiency.

However, the real significance of the climate-security event lay not in what these leaders said, but that they were there to say it at all. Not many issues can gather the heads of the AU, NATO, and the UNDP on the same platform, alongside the foreign ministers of Sweden and Denmark. This event proved that climate change has become a core concern of international policymakers.

The only way to tackle global problems, as Ping argued, is to find global solutions. And a clear understanding of the potentially devastating security implications of climate change might be one way to bring about those global solutions.

“We are all in the same ship, and if that ship sinks, we will all drown,” said Ping.

Oli Brown is senior researcher and program manager at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Read more of IISD’s postings on its blog.

Photo: Courtesy United Nations Photo. -

Development Seeking its Place Among the Three “Ds”

›December 15, 2009 // By Dan Asin“By one count, there are now over 140 goals and priorities for U.S. foreign assistance,” Senator John Kerry said during the nomination hearing for USAID Administrator-designate Rajiv Shah. If Shah is confirmed, his principal tasks will be moving development out from the shadow of defense and diplomacy and bringing definition to USAID’s mission.

“USAID needs to have a strong capacity to develop and place and deploy our civilian expertise in national security areas,” Shah said at his nomination hearing. USAID “has a responsibility to step up and offer very clear, visible, and understood strategic leadership,” as well as clarify “the goals and objectives of resources that are more oriented around stability goals than long-term development goals.”

A difficult task—and whether Shah wants it or not, he’ll get plenty of help from State, the Obama Administration, and Congress.

State Department Reviews Diplomacy and Development

The State Department’s Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR)—launched in July by Shah’s impending boss, Secretary of State Hilary Clinton—will certainly inform his USAID vision. Modeled after the Defense Department’s Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), the QDDR is designed to enhance coordination between USAID and State.

Anne-Marie Slaughter, director of policy planning at the State Department and co-leader of the review process, laid out the QDDR’s specific goals at a recent event hosted by the Center for American Progress:- Greater capacity for, and emphasis on, developing bilateral relationships with emerging nations, working within multilateral institutions, and working with non-state actors

- Capability to lead “whole-of-government” solutions to international challenges

- More effective coordination between top-down (diplomatic) and bottom-up (development) strategies for strengthening societies

- Greater capacity to launch on-the-ground civilian responses to prevent and respond to crises

- Flexible human resource policies regarding the hiring and deployment of contractors, foreign service officers, and development professionals

Obama Administration, Congress Also Join In

Details on the Presidential Study Directive (PSD) on Global Development Policy—outside its broad mandate for a government-wide review of U.S. development policy—are similarly sparse. The directive’s fuzzy parameters leave open the potential for its intrusion into the QDDR’s stated objectives.

But from what little is available, both the QDDR and PSD appear to be part of complementary efforts by the Obama administration to elevate development’s role in U.S. foreign policy, using whole-of-government approaches.

Lest Congress be left out, each chamber is working on its own development legislation. Senators John Kerry and Richard Lugar’s Foreign Assistance Revitalization and Accountability Act of 2009 (S. 1524) seeks “to strengthen the capacity, transparency, and accountability of United States foreign assistance programs to effectively adapt and respond to new challenges.” The act would reinforce USAID by naming a new Assistant Administrator for Policy and Strategic Planning, granting it greater oversight over global U.S. government assistance efforts, and strengthening its control over hiring and other human resource systems.

Congressmen Howard Berman and Mark Kirk’s Initiating Foreign Assistance Reform Act of 2009 (H.R.2139) would require the president to create and implement a comprehensive global development strategy and bring greater monitoring and transparency to U.S. foreign assistance programs.

Successful legislation in the Senate and House could pave the way for the reformulation of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, whose message has been rendered complicated and sometimes contradictory by decades of amendments.

And all these ambitious efforts are complicated by the involvement of 25 independent government agencies in U.S. foreign assistance—a formidable challenge to any administrator.

Photo: Courtesy of the USDA. -

U.S. Policy on Post-Conflict Health Reconstruction

›December 8, 2009 // By Calyn Ostrowski Stabilizing and rebuilding state infrastructure in post-conflict settings has been increasingly recognized as critical to aiding the population and preventing renewed conflict. The United States has increasingly invested in rebuilding health systems, and in some cases assisting in the delivery of health services for the first time.

Stabilizing and rebuilding state infrastructure in post-conflict settings has been increasingly recognized as critical to aiding the population and preventing renewed conflict. The United States has increasingly invested in rebuilding health systems, and in some cases assisting in the delivery of health services for the first time.

While global health concerns have recently received significant attention, as witnessed by President Obama’s Global Health Initiative, the importance of health system reconstruction to stabilization efforts remains unevenly recognized. On November 10, 2009, experts met at the Global Health Council’s Humanitarian Health Caucus to discuss investing in health services in the wake of war and the challenges of funding this investment.

“Deconstruction from violence extends beyond the time of war and often leads to severe damage of health infrastructure, decreased health workers, food shortages, and diseases…resulting in increased morbidity and mortality from causes that are not directly related to combat,” shared Leonard Rubenstein, a visiting scholar at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. Rubenstein argued that while relieving suffering in post-conflict settings should be a sufficient reason to include health reconstruction in U.S. foreign policy, policymakers narrowly define rationales for engagement based on claims that investments increase peace and improve the image of the U.S. government.

Investing in Health Systems Builds State Legitimacy

The evidence for investing in health systems to deter future conflict is limited and this approach is dangerous, according to Rubenstein, because it distorts spending decisions and fails to consider comprehensive capacity development strategies. Additionally, the Department of Defense’s approach of “winning the hearts and minds” is too short-term and neither linked to “system-building activities that are effective and sustainable…nor consistent with advancing the health of the population,” he said.

Instead, Rubenstein recommended that the United States invest in health systems after conflict because it advances state legitimacy. Although additional evidence is necessary, Rubenstein maintains that the promotion of state legitimacy enhances the perception that the government is responding to their long-term needs and encourages local ownership and accountability. Developing health systems in post-conflict settings is complex and cannot be done quickly, he noted, and thus increased financial and human resource capacities will be essential.

Coordination and Transition Funding

“We need to recognize that the U.S. is not the only funder, as there are many stakeholders involved,” argued Stephen Commins, strategy manager for fragile states at the International Medical Corps. Commins argued that there is a “desperate need to coordinate donor funding … both within and across government systems, as well as an increased need for transparent donor tracking systems.”

As countries come out of conflict and start to gain government legitimacy, they need increased support to stabilize conflict and avoid collapse. Transition funding for health systems needs to support both short and long-term efforts, maintained Commins, but unfortunately the donors driving these timelines are often driven by self-interest, not the rights of the individual living in conflict.

Without a transparent donor tracking system, it is hard to demonstrate actual monetary disbursements versus commitments, so Commins called for a system that tracks allocations and spending in real time. These are not our countries, he argued, and responding to health systems in post-conflict settings should be tailored to the country’s needs, not the donor’s. He also called for increased research that describes, over time, the costs for rebuilding and transitioning from international NGO-driven systems to self-sustained governments.

Rebuilding Health Systems in Sudan

George Kijana, health coordinator in southern Sudan for the International Rescue Committee, discussed reasons for why Sudan’s health system remains poor five years after conflict. According to Kijana, the government in Southern Sudan has not been held accountable by its donors, leading to a breakdown in infrastructure and a lower quality of health workers.

Additionally, a majority of the available health data comes from non-state actors that are not easily accessible. Kijana shared that in order for Sudan to move forward, more research and data are needed to help target long-term capacity building projects, as well as short-term interventions that address infant and maternal mortality. While progress is slow, he pointed out encouraging signs of progress, as the Ministry of Health now recognizes their weaknesses and positively engages with its development partners such as the United Nations.

Photo: Romanian Patrol administers medical treatment to Afghan communities, courtesy of Flickr user lafrancevi.

-

Start With A Girl: A New Agenda For Global Health

›November 16, 2009 // By Calyn OstrowskiThe Center for Global Development’s latest report, Start With A Girl: A New Agenda For Global Health, sheds light on the risks of ignoring the health of adolescent girls. Like other reports in the Girls Count series, it links broad social outcomes with adolescent health. “Adolescence is a critical juncture for girls. What happens to a girl’s health during adolescence determines her future–and that of her family, community, and country,” state coauthors Miriam Temin and Ruth Levine.

Between childhood and pregnancy, adolescent girls are largely ignored by the public health sector. At the same time, programs and policies aimed at youth do not necessarily meet the specific needs of girls. Understanding the social forces that shape girls’ lives is imperative to improving their health.

Like recent books by Michelle Goldberg and Nicholas Kristof, the report argues for increased investment in girls’ education to break down the social and economic barriers that prevent adolescent girls from reaching their full potential. Improving adolescent girls’ health will require addressing gender inequality, discrimination, poverty, and gender-based violence.

“For many girls in developing countries, well-being is compromised by poor education, violence, and abuse,” say Temin and Levin. “Girls must overcome a panoply of barriers, from restrictions of their movement to taboos about discussion of sexuality to lack of autonomy.” The report points to innovative government and NGO programs that have successfully changed negative social norms, such as female genital cutting and child marriage. However, the authors urge researchers to examine the cost-effectiveness and scalability of these programs.

In the last five years, the international community has become increasingly aware of the importance of youth to social and economic development. Some new programs are focused on investing in adolescent girls, such as the World Bank’s Adolescent Girls Initiative and the White House Council on Women and Girls, but significant additional investment and support is needed.

“Big changes for girls’ health require big actions by national governments supported by bilateral and multilateral donor partners, international NGOs…civil society and committed leaders in the private sector,” maintain Temin and Levin. They offer eight recommendations:

1. Implement a comprehensive health agenda for adolescent girls in at least three countries by working with countries that demonstrate national leadership on adolescent girls.

2. Eliminate marriage for girls younger than 18.

3. Place adolescent girls at the center of international and national action and investment on maternal health.

4. Focus HIV prevention on adolescent girls.

5. Make health-systems strengthening and monitoring work for girls.

6. Make secondary school completion a priority for adolescent girls.

7. Create an innovation fund for girls’ health.

8. Increase donor support for adolescent girls’ health.

“We estimate that a complete set of interventions, including health services and community and school-based efforts, would cost about $1 per day,” say the authors of Start With a Girl. There is no doubt in my mind that this small investment would indeed have a high return for the entire global community.

Showing posts from category foreign policy.

“It’s not every day you find an issue where effective diplomacy and development will allow you to save millions of lives, feed the hungry, empower women, advance our national security interests, protect the environment, and demonstrate to billions of people that the United States cares. Water is that issue,” declared Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at a

“It’s not every day you find an issue where effective diplomacy and development will allow you to save millions of lives, feed the hungry, empower women, advance our national security interests, protect the environment, and demonstrate to billions of people that the United States cares. Water is that issue,” declared Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at a

Leaders from the African Union,

Leaders from the African Union,

Stabilizing and rebuilding state infrastructure in post-conflict settings has been increasingly recognized as critical to aiding the population and preventing renewed conflict. The United States has increasingly invested in rebuilding health systems, and in some cases assisting in the delivery of health services for the first time.

Stabilizing and rebuilding state infrastructure in post-conflict settings has been increasingly recognized as critical to aiding the population and preventing renewed conflict. The United States has increasingly invested in rebuilding health systems, and in some cases assisting in the delivery of health services for the first time.