-

Population and Sustainability in an Unequal World

›August 13, 2012 // By Laurie MazurJune’s Rio + 20 Conference on Sustainable Development left environmentalists little to cheer about. Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace International, called the meeting “a failure of epic proportions.” And Washington Post reporter Juliet Eilperin said the conference “may produce one lasting legacy: convincing people it’s not worth holding global summits.”

-

Iran’s Surprising and Shortsighted Shift on Family Planning

›August 8, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy Madsen

In late July, Iran’s government announced that it would no longer fund family planning programs, a dramatic reversal following 20 years of support. The change is especially abrupt for a country that has been lauded as a family planning success story, with thorough rural health services and an educated female population contributing to one of the swiftest demographic transitions in history.

-

A Roundup of the ‘Global Trends 2030’ Series on Population Aging

›

The National Intelligence Council is trying something new for this year’s Global Trends report: keeping a blog. So far, there have been postings from analysts and contributors on everything from migration and urbanization to international banking and precision strike capabilities, but over the past week, one of the most extensive series yet went up on demography. Though youth bulge theories have often dominated population-related security discussions, 11 posts highlight the newest and least understood of all demographic conditions: advanced population aging.

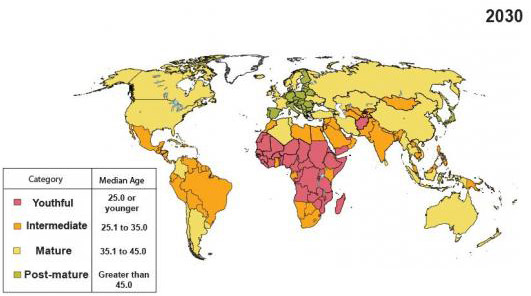

In parts of the world, mainly Europe and several countries in East Asia, populations are set to become “extremely mature” because of sustained declines in average fertility to very low levels and steady increases in lifespan. Demographers measure maturity by a population’s median age – the age of the person for whom precisely half of the population is younger and half older. Japan and Germany currently have the most mature populations; both are reported to have a median age slightly over 45 years. By 2030, UN Population Division and U.S. Census Bureau projections suggest that there may be between 19 and 29 countries that pass this benchmark. In Japan, the median age is projected to be 51.

If 5 out of 10 people in a country over 50 years old sounds unprecedented, that’s because it is. In this series, titled “Population Aging to 2030,” a group of political demographers, economic demographers, political scientists, and historians discuss the implications of this never-before-experienced set of age structures.

In his introductory essay, “Population Aging: A Demographic and Geographic Overview” (cross-posted here on New Security Beat), Richard Cincotta outlines the upcoming demographic trend, identifying the particulars of these novel age structures and indicating the regions that are expected to mature into economically and politically advantageous and disadvantageous demographic profiles.

In “Population Aging – More Security or Less?,” Jack Goldstone examines the effects on the U.S. military of a maturing developed world. With the United States and their traditional allies having proportionally fewer young people, will this impact limit their ability to put “boots on the ground?” Can new partnerships be developed in order to make up for this shortfall in man power?

In “China: the Problem of Premature Aging,” Richard Jackson focuses on China’s unique set of aging issues. Due to strict immigration laws and the one-child policy, China is experiencing the most rapid aging of the major powers. The favorable age structure which has enabled huge economic growth will soon shift to being a major burden on a relatively smaller working-age population, having potential political and societal consequences beyond that.

“The Sun Has Yet to Set on China” provides a different interpretation of the challenges China faces. Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba argues that although there will be changes in age structure, the problems may be overstated and the United States may still face a challenge to its status as sole global superpower.

In “Population Aging and the Welfare State in Europe,” Ronald Lee and Andrew Mason emphasize the stresses aging will exert on the extensive social welfare programs of many European states. The combination of longer life expectancy and declining fertility rates has led to a large and increasing funding gap in the welfare system, leaving questions as to the future viability of these programs.

In “Population Aging and the Future of NATO,” Mark Haas foresees that the welfare funding gap could have far-reaching international security consequences. With European governments diverting more and more resources away from military spending to fund welfare programs, the current U.S. irritation with NATO is likely to continue, as European allies “free ride” on the back of U.S. military supremacy in order to cut their defense budgets.

In “The Beginning of History: Advanced Aging and the Liberalness of Democracies,” Richard Cincotta examines the future of the liberal democratic political systems across aging countries. With increasing pressure on resources and a large disparity likely between the native born and migrant populations, it may become challenging for these states to remain liberal and democratic.

For Toshi Yoshihara, author of “The Strategic Implications of Japan’s Demographic Decline,” the aging process will pose a question of priorities for the leaders of Japan. The decreasing number of personnel available to the military, the effects of which were highlighted by the recent tsunami, will force a strategic decision between a defense force that is prepared primarily to address immediate and local security threats or one that is trained primarily for broader humanitarian interests.

“A Demographic Sketch of a Reunified Korea” provides interesting insights into the hypothetical demography of a single, unified Korea. Putting aside the two very distinct social paths that evolved during the past 60 year, Elizabeth Hervey Stephen uses demographic projections to envisage the challenges and opportunities that could arise from reunification.

David Coleman points to immigration as a possibly-mitigating force to aging in the developed world. In “The Impact of Immigration on the Populations of the Developed World and Their Ethnic Composition,” Coleman concludes that the developed world is likely to become “super diverse” by 2030. But this trend can be volatile. International migration is subject to many political and economic factors, bringing into question whether the developed world can rely on migration to supplement their native growth rates.

In “The Ethnic Future of Western Europe to 2030,” which wraps up the series, Eric Kaufmann examines the ethnic make-up of Western Europe in the coming decades. While the size of ethnic minority populations may be smaller than in the United States, the speed of growth in these minorities is likely to be much more rapid in Western Europe. This unprecedented increase in migrant populations could exacerbate ethnic social tensions, particularly in urban areas.

The broad nature of these essays suggests that advanced population aging will emerge within the context of many types of policy debates in the coming decades. While these 11 brief essays only scratch the surface of their respective areas of research, they provide a broad introduction to the politics of advanced population aging.

Jonathan Potton is a student at the University of Aberdeen and currently interning at the Stimson Center for demographer Richard Cincotta.

Sources: UN Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau.

Image Credit: Courtesy of Richard Cincotta. Data from U.S. Census Bureau’s international database. -

From Youth Bulge to Food and Family Planning, Los Angeles Times’ ‘Beyond 7 Billion’ Series Synthesizes Population Challenges

›Over the next 40 years, the world is set to add 2.3 billion people. Millions more will join the middle class, pushing consumption upwards and further straining the world’s natural resources. Variables like climate change and political instability will exacerbate that strain and complicate efforts to bolster peaceful and stable development. Los Angeles Times correspondent Kenneth Weiss and photographer Rick Loomis examine these numerous and interconnected challenges in a five-part series on population growth and consumption dynamics.

Speaking to demographic and health experts (including a number of New Security Beat regulars, like Richard Cincotta, Jon Foley, and Dr. Joan Castro), Weiss provides a thorough, astute, and compelling assessment of population dynamics in a rapidly changing world. The series starts with a basic introduction to population, climate, and consumption dynamics and progresses through to discuss political demography, global food security, and detailed looks at two important case studies, China and the Philippines.

Part One: A Population Primer

Population growth alone poses a number of challenges as cities become more crowded and demand for basic resources like water and food outpaces supply. Climate change and the unpredictable and sometimes extreme weather that is its hallmark “will make all of these challenges more daunting,” writes Weiss. And “population will rise most rapidly in places least able to handle it.” Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, already expected to bear the brunt of climate change with rising sea levels, shorter growing seasons, and increasingly variable weather patterns, will also have to support the bulk of the world’s population growth by mid-century. Populations in Europe, North America, and East Asia are expected to stay stable or decline in numbers.

The magnitude of growth in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, however, is uncertain. What happens from here “hinges on the cumulative decisions of hundreds of millions of young people around the globe,” Weiss writes. And yet, “population growth has all but vanished from public discourse.” Family planning in particular remains hamstrung by “erratic funding and unpredictable crosscurrents.” The result, he writes, is that even “under the best conditions, it’s hard to get contraceptives into the hands of impoverished women who want them.”

Part Two: The Arc of Instability

Drawing on work from demographer Richard Cincotta, George Mason University’s Jack Goldstone, Population Action International, and others, part two of Weiss’ series examines youth bulges and the so-called “arc of instability,” stretching across the disproportionately youthful countries of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

When a large youth population is mixed with other societal conditions, like “religious and ethnic friction, political rivalries, economic disparities, or food shortages,” youth can be “the kindling” for a spark that ignites simmering tensions, writes Weiss. Afghanistan is a case in point, where unemployed young men are often turning to the Taliban not out of extremist fervor, but out of a desperate need to support themselves and their families. “It’s too hard to employ this many people and too easy to recruit them into violence,” Cincotta told Weiss.

And Afghanistan is just the beginning, according to Goldstone. “We are literally going to see one billion young people come into the populations in the arc of instability over the next two decades,” he said. “We can’t fight them. We have to figure a better way to help them.”

Part Three: Feeding a Growing Population

As the world’s population continues to grow, and as more families join the middle class, world food production will have to double by mid-century in order to meet future demand. “What that actually means,” says World Wildlife Fund’s Jason Clay, an agriculture specialist, “is that in the next 40 years we need to produce as much food as we have in the last 8,000.”Jon Foley on how to feed nine billion and keep the planet

Weiss presents the Horn of Africa and Punjab as microcosms of the problems facing global food production in the 21st century. Desertification and urbanization are eating away at potential cropland, while harmful farming techniques leech essential nutrients from soil, rendering it useless for future use. Insufficient infrastructure means that food spoils as it’s shipped from where it’s produced to where it’s needed, while extreme and widespread poverty means that those most in need can’t afford enough to feed their families.

Stuck between growing demand and restricted supply, the University of Minnesota’s Jonathan Foley said the challenge of the century is straightforward: “How will we feed nine billion people without destroying the planet?”

Part Four: Population and Consumption in China

China has “a greater collective appetite – and a greater ecological impact – than any other country,” writes Weiss, making it a prime example of “how rising consumption and even modest rates of population growth magnify each other’s impact on the planet.”

The country’s one-child policy slowed population growth rapidly, cutting fertility almost in half in less than a decade. Over time, a large working-age cohort with few dependents emerged, and helped China reap a demographic dividend. The resulting economic prosperity has come at a cost, however, as rising incomes and increasing consumption, spread across 1.3 billion people, have wreaked havoc on the country’s environment on a scale not seen anywhere else in the world.

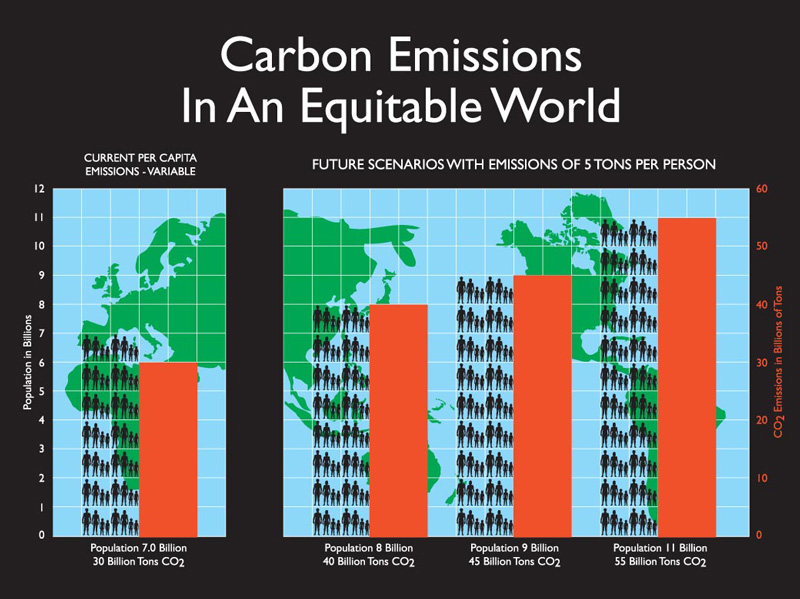

Because of that scale, what happens in China will have global repercussions. Climate scientists “say that in order to avoid a potentially catastrophic rise in global temperatures, worldwide carbon dioxide emissions must be cut in half by 2050,” Weiss writes. “For that to happen, China’s emissions would have to peak by 2020” – 15 years earlier than official government projections. The government remains opposed to further limits on emissions, arguing that such limits would “cripple” economic growth – an unfair impediment considering that developed countries were able to “pollute their way to prosperity, their argument goes.”

Part Five: Family Planning in the Philippines

Weiss ends the series with an in-depth look at family planning in the Philippines – a country at the forefront of the global debate over access to contraception. Lawmakers in the 80-percent-Catholic country have steadfastly refused to fund family planning services, while support from the international community all but vanished when USAID, “the major donor of contraceptives to the Philippines,” said in 2008 that it would end its contraceptive program.

Today, half of all pregnancies in the Philippines are unintended. Lawmakers are considering a “reproductive health bill…call[ing] for public education about contraceptives and government subsidies to make them available to everyone,” but a powerful opposition, including Church leadership, has stalled the bill for 14 years, Weiss writes.Joan Castro on population-environment programing in the Philippines

Public officials, including the former Manila mayor who ended the city’s contraceptive program 12 years ago, portray unbridled population growth as an economic asset, saying that “when you have more people, you have a bigger labor force.” For the millions of Filipinos who live in poverty, however, the lack of affordable family planning services leaves them with little control over family size and puts the Philippines on track to grow from 96.4 million people today to 154.9 million by mid-century. At that rate, the Philippines would be Asia’s third fastest growing country, behind Timor Leste and Afghanistan.

Not everything in the series is dire – there are side columns highlighting population, health, and environment programming in Uganda, Iran’s successful family planning program, and Dr. Joan Castro’s family planning and marine conservation work in the Philippines. But Weiss is not naïve about the challenges ahead. Under any of the United Nation’s population projections, “living conditions are likely to be bleak for much of humanity,” he writes. “Water, food, and arable land will be more scarce, cities more crowded, and hunger more widespread.”

“Even under optimistic assumptions, the toll on people and the planet will be severe.”

But while the population challenges facing the world are many, Weiss, like many before him, makes one argument clear: providing family planning services to the 222 million women who want to control the number of children they have but cannot would go a long way towards minimizing future strain.

Be sure to check out the photo and video features accompanying the “Beyond 7 Billion” series on the feature site.

Note: The sentence beginning with “When a large youth population…” was corrected.

Sources: Los Angeles Times, UN Population Division.

Video Credit: “The Challenge Ahead,” used with permission courtesy of the Los Angeles Times; Photo: “Dharavi,” used with permission courtesy of Rick Loomis/Los Angeles Times; Jon Foley video: TEDx. -

PBS ‘NewsHour’ Reports on Reasons for Optimism Amid Niger’s Cyclical Food Crises

›Set in the middle of the arid region between the Sahara desert and the equatorial savannas of Africa known as the Sahel, Niger is no stranger to drought. In recent years, however, droughts have hit more often, started earlier in the season, and lasted longer, creating a cycle of food insecurity that is becoming more difficult to break.

-

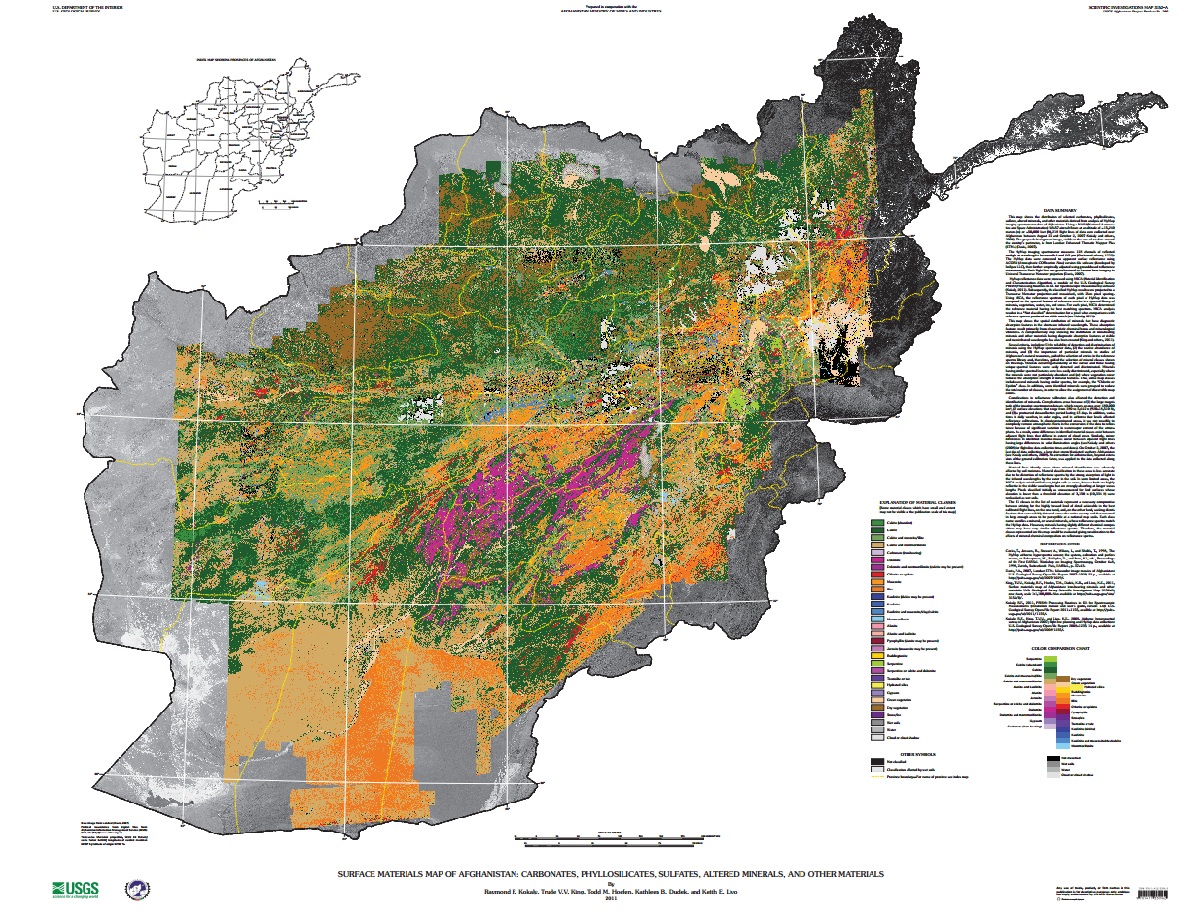

New USGS Report and Maps Highlight Afghanistan’s Mineral Potential, But Obstacles Remain

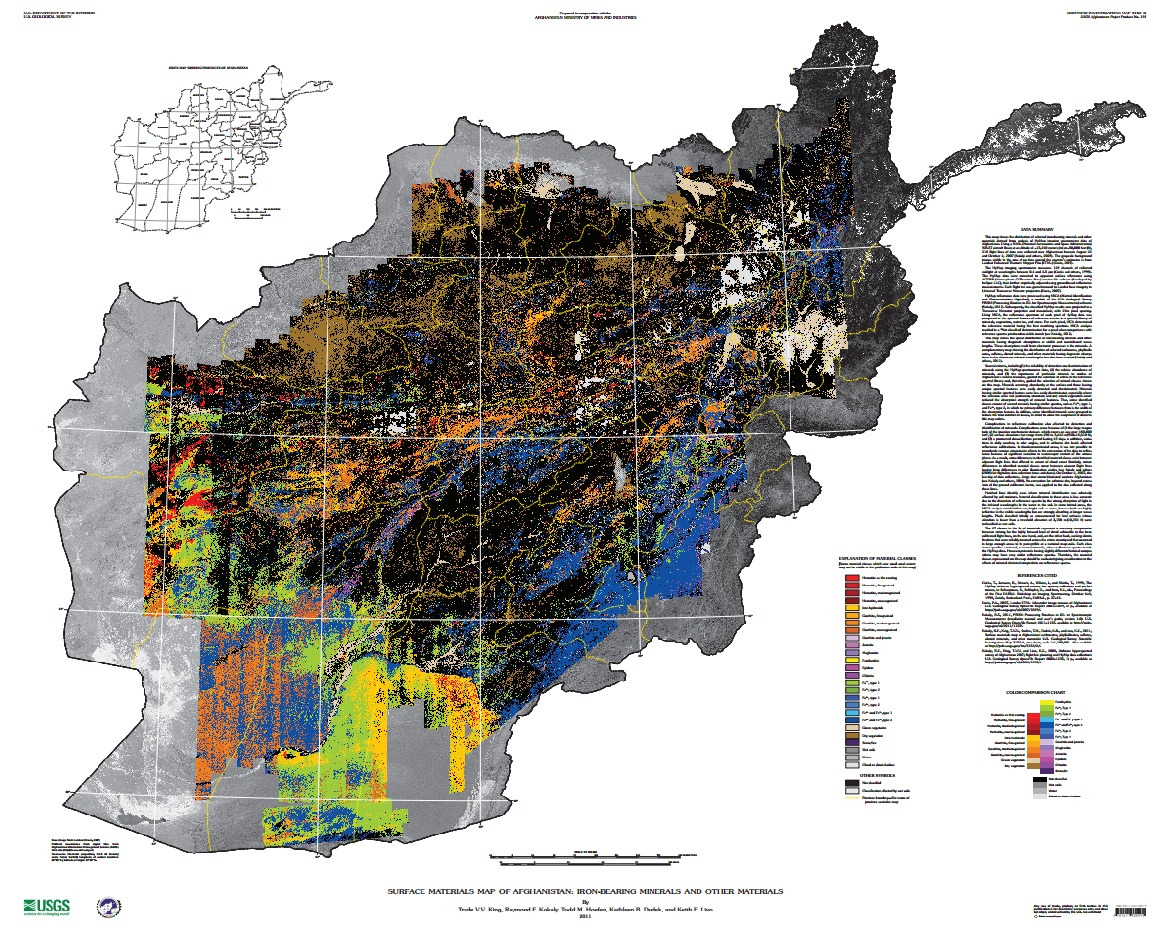

›Two maps released to the public for the first time this month illustrate the vast wealth of mineral deposits in the war-torn nation of Afghanistan. The maps, created through a joint effort from the U.S. Geological Survey and Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations, are the first of their kind to provide large-scale coverage of a country using a technology called hyperspectral imaging, which measures the reflectance of material on the Earth’s surface simultaneously across a continuous band of wavelengths broken up into 10 to 20 nanometer intervals. More than 800 million individual pixels of data were collected during a period of 43 days in 2007 by a NASA aircraft. Each data point was then “compared to reference spectrum entries in a spectral library of minerals, vegetation, water, ice, and snow in order to characterize surface materials across the Afghan landscape.”

Two maps released to the public for the first time this month illustrate the vast wealth of mineral deposits in the war-torn nation of Afghanistan. The maps, created through a joint effort from the U.S. Geological Survey and Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations, are the first of their kind to provide large-scale coverage of a country using a technology called hyperspectral imaging, which measures the reflectance of material on the Earth’s surface simultaneously across a continuous band of wavelengths broken up into 10 to 20 nanometer intervals. More than 800 million individual pixels of data were collected during a period of 43 days in 2007 by a NASA aircraft. Each data point was then “compared to reference spectrum entries in a spectral library of minerals, vegetation, water, ice, and snow in order to characterize surface materials across the Afghan landscape.”

Accompanying the release of the maps is a USGS study, completed in September of 2011, that largely confirms earlier reports from the DOD and USGS on the size of Afghanistan’s untapped mineral resources. The first reports received widespread media coverage last year, and updated estimates indicate that upwards of $900 billion worth of mineral reserves are present in a number of different forms including copper, iron, gold, and, most notably, more than one million metric tons of rare earth elements.

Scientists involved with the project believe that there may be even more reserves awaiting discovery. “I fully expect that our estimates are conservative,” said Robert Tucker from the USGS in an interview with Scientific American. “With more time, and with more people doing proper exploration, it could become a major, major discovery.”

Over the course of the study, scientists from the USGS and Afghan Geological Survey combined the newly-created spectral data with existing maps to identify 24 areas of interest (AOIs) that warranted hands-on investigation.

The two hyperspectral maps illustrate different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Shortwave infrared wavelengths reveal carbonates, phyllosilicates, and sulfates, while visible and near-infrared wavelengths show iron-bearing minerals, which yield products ranging from copper to rare earth elements and uranium. Each map classifies 31 different types of materials by color.

Although the hyperspectral maps only show mineral deposits on the surface, geologists were able to estimate what lies beneath by combining new data with samples previously taken from trenches, drill holes, or underground workings at the AOIs by Soviet and Afghan scientists. According to the USGS, “A number of the AOIs were field checked by USGS and DOD geologists between 2009 and 2011, and the previous geologic interpretations and concepts were confirmed.”

Actual Extraction: Not Easy

Afghanistan has been “scouring the globe for investors to develop its mines in an attempt to lift one of the world’s poorest nations out of misery through investment,” according to The Wall Street Journal. Contracts have already been awarded to China and India to develop copper and iron mines, respectively, and another round of bidding is currently in progress for four unexploited sites that are being closely eyed by countries such as the United States, Australia, and Turkey.

But significant hurdles remain in the quest to turn Afghanistan’s buried minerals into a steady source of income for the government and the Afghan people. Security is still a major concern and United States will pull out a vast majority of its combat troops by 2014. The government has established a Mines Protection Unit to guard sites where ground has already been broken, and plans to increase the size of the unit as necessary to provide security for all mining projects nationwide. For now the Afghan Ministry of Mines is only taking bids for projects in the more secure northern part of the country, where deposits of copper and gold are located. As the nation develops and stabilizes, massive resources of rare earth elements located in the notoriously volatile Helmand Province will open for bids.

Security isn’t the only factor affecting the country’s mining prospects. “If you want to do mineral resource development, there are two things you need to pay attention to: water and energy resources. Where is the power going to come from? You can’t develop these large mineral deposits without energy,” said director of the USGS program in Afghanistan, Jack Medlin, in an interview with EARTH magazine.

There are also the traditional pitfalls of developing extractive industries, especially in poor and conflict-prone countries, including corruption, inequity, land disputes, and environmental degradation. And the fact that Afghanistan is landlocked, making supply lines in an out of the country difficult (as the United States has discovered).

Despite the many hurdles, there is plenty of optimism for an Afghan future brightened by mineral wealth. The new data shows that previous reports of substantial resources were not far off, and the Afghan economy, which for years has relied on opium as its biggest export, could certainly use the help. “The prognosis is extremely encouraging and could play a significant role in recovery from decades of war,” USAID advisor Wayne Pennington told EARTH.

For the full resolution versions of the hyperspectral imaging maps (~90MB each) see here and here.

Keenan Dillard is a cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point and an intern with the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program.

Sources: Afghan Geological Survey, Afghan Ministry of Mines, Christian Science Monitor, U.S. Department of Defense, EARTH, The New York Times, Scientific American, U.S. Geological Survey, The Wall Street Journal, World Bank.

Image Credit: USGS.

-

Bringing Environment and Climate to the 2012 Population Association of America Annual Meeting

›June 5, 2012 // By Sandeep BathalaOver 2,100 participants attended the 2012 Population Association of America (PAA) annual meeting in San Francisco this May. PAA was established in 1930 to research issues related to human population. This year, for the first time, the meeting featured a notable contingent of demographers, sociologists, and public health professionals working on environmental connections.

I followed as many of the environment-population discussions on newly published or prospective research papers as possible (about 20 in total). I found four papers particularly noteworthy for the connections made to women, family planning, and climate change adaptation.

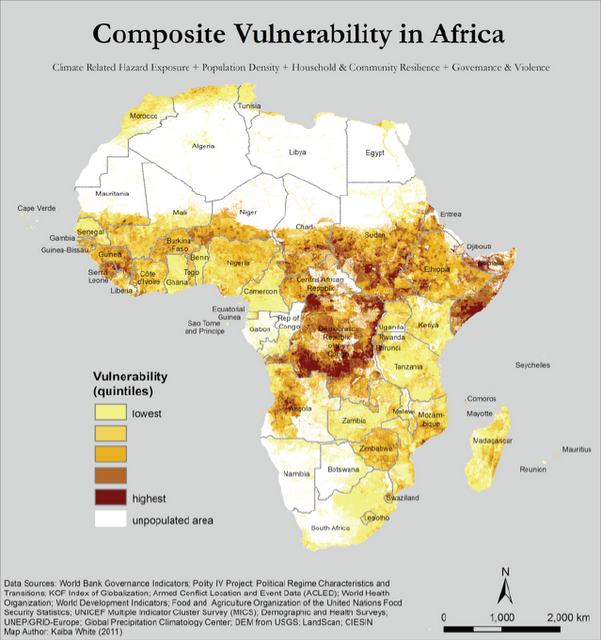

Samuel Codjoe of the University of Ghana spoke about adaptation to climate extremes in the Afram Plains during one of the population, health, and environment (PHE) panels organized by Population Action International. Although developed nations are historically the major contributors of greenhouse gases due to comparatively high levels of consumptions, developing countries are the most vulnerable to the consequences of climate change – in part because of continued population growth. As a result, adaptation strategies in countries like Ghana are particularly important; and given women’s often-outsized role in water and natural resource issues, a focus on gender-specific adaptation even more so.

Codjoe presented an analysis of preferred adaptation strategies to flood and drought, broken down by gender and three common occupations – farming, fishing, and charcoal production). He said he hopes his assessment – part of a collaborative research effort with Lucy K.A. Adzoyi-Atidoh of Lincoln University – will aid in the selection and implementation of successful adaptation options for communities and households in the future.

“Understanding differences in the priorities that women place on adaptation may prove to be important in the effectiveness of climate change adaptation – and the sustainability of communities,” he said.

David López-Carr of the University of California, Santa Barbara, speaking on behalf of a group of researchers with World Wildlife Fund, teased out the gender dynamic further when he presented on ways to help the conservation sector determine next steps for existing PHE projects. Practitioners from seven of the eight PHE projects currently implemented by conservation organizations (defined by having been involved for at least three years in bringing family planning to local communities) recently said the links to women’s empowerment were among the most important aspects of successful projects.

López-Carr therefore emphasized the need for additional research on how PHE projects can support and empower women, both economically and socially. He also noted, like Codjoe, the potential impact women often have on the management of their community’s natural resources, saying this was another area where research on the empowering effect of PHE programs can provide further backing for integrated programs.

Karen Hardee of Futures Group spoke about how the experiences of integrated PHE projects, despite most not being designed to respond to climate change specifically, have lessons to offer climate change efforts. Her work was done in partnership with the Population Reference Bureau, Population Action International, and U.S. Agency for International Development. She concluded that community-based adaptation approaches should consider population dynamics in vulnerability assessments. Meeting unmet need for family planning, she said, can assist communities adapting to climate change by building resilience. And as result, “PHE approaches should be able to qualify for funding under community-based adaptation programs.”

Shah Md. Atiqul Haq of the City University of Hong Kong presented research he conducted in Bangladesh that found that women tended to feel that a large family size was not advantageous during floods. This, he said, was indicative of their increased understanding of vulnerability and an endorsement of providing knowledge and access to family planning services as part of climate change adaptation strategies.

The inclusion of more environment, and particularly PHE, related presentations at this year’s conference was good to see – perhaps a sign that demography is becoming a more complex and comprehensive field, with a focus more on population structure and its interactions with other issues, rather than a singular fascination with growth.

In particular, panelists showed that the nexus between demography, gender equity, and climate change continues to grow in importance, both in the research and practitioner communities.

Photo Credit: Tribal women and children in Kerala state, India, courtesy of flickr user Eileen Delhi. -

New Research on Climate and Conflict Links Shows Challenges for the Field

›

“We know that there will be more conflicts in the future as a result of climate change than there would have been in a hypothetic world without climate change,” said Marc Levy, deputy director of the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, although existing data and methodologies cannot predict how many additional conflicts there will be, or which causal factors will matter most. [Video Below]

Showing posts from category featured.