Showing posts from category environment.

-

Eddie Walsh, The Diplomat

Indonesia’s Military and Climate Change

›July 22, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Eddie Walsh, appeared on The Diplomat’s ASEAN Beat blog.

With more than 17,000 islands and 80,000 kilometers of coastline, Indonesia is extremely vulnerable to climate change. Analysts believe that rising temperatures will almost certainly have a negative impact on human security in Indonesia, which in turn will increase the probability of domestic instability and introduce new regional security concerns. With this in mind, it’s important that Indonesia’s armed forces take a range of measures to prioritize environmental security, including procuring new equipment, strengthening bilateral and multilateral relations, and undertaking training for new roles and missions.

Indonesians are expected to experience warmer temperatures, increased precipitation (in the northern islands), decreased precipitation (in the southern islands), and changes in the seasonality of precipitation and the timing of monsoons. These phenomena could increase the risk of either droughts or flooding, depending on the location, and could also reduce biodiversity, lead to more frequent forest fires and other natural disasters, and increase diseases such as malaria and dengue, as well incidences of diarrhea.

The political, economic, and social impact of this will be significant for an archipelago-based country with decentralized governance, poor infrastructure, and a history of separatist and radical conflict. According to a World Bank report, the greatest concern for Indonesia will be decreased food security, with some estimates projecting variance in crop yields of between -22 percent and +28 percent by the end of the century. Rising sea levels also threaten key Indonesian cities, including Jakarta and Surabaya, which could stimulate ‘disruptive internal migration’ and result in serious economic losses. Unsurprisingly, the poor likely will be disproportionately impacted by all of this.

Continue reading on The Diplomat.

Sources: World Bank.

Photo Credit: “Post tsunami wreckage Banda Aceh, Sumatra, Indonesia,” courtesy of flickr user simminch. -

Failed States Index 2011

›“The reasons for state weakness and failure are complex, but not unpredictable,” said J.J. Messner, one of the founders of the Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index, at the launch of the 2011 version of report in Washington last month. The Index is an analytical tool that could aid policymakers and governments seeking to prevent and mitigate state collapse by identifying patterns of underlying drivers of state instability.

The Index ranks 177 countries according to 12 primary social, economic, and political indicators based on analysis of “thousands of news and information sources and millions of documents” and distilled into a form that is meant to be “relevant as well as easily digestible and informative,” according to the creators. “By highlighting pertinent issues in weak and failing states,” they write, the Index “makes political risk assessment and early warning of conflict accessible to policymakers and the public at large.”

Common Threats: Demographic and Natural Resource Pressures

The Index reveals that half of the 10-most fragile states are acutely demographically challenged. The composite “Demographic Pressures” category takes into account population density, growth, and distribution; land and resource competition; water scarcity; food security; the impact of natural disasters; and public health prevention and control. Additional population indices are found in “Massive Movement of Refugees or Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs),” and health indicators, including infant mortality, water, and sanitation, are spread across several categories.

Not surprisingly, some of the most conflict-ridden countries show up at the top of the list. The Index highlights some of the lesser known issues that contribute to their misery: demographic and natural resource stresses in Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen (a list that would include Palestine, if inclusion in the Index were not contingent on UN membership); the DRC’s conflict minerals; and Somalia and Sudan’s myriad of environmental and migration problems, which play major roles in their continued instability.

Haiti, with its poor health and lack of infrastructure and disaster resilience, was deemed the Index’s “most-worsened” state of 2011. The January 2010 earthquake and its ensuing “chaos and humanitarian catastrophe” demonstrated that a single event can trigger the collapse of virtually every other sector of society, causing what Messner termed the “Humpty Dumpty effect” – while a state can deteriorate quickly, it is much harder to put it back together again.

The inclusion of natural resource governance within the social and economic indicators would render the Index a more complete analytical tool. In a 2009 report, the UN Environment Program (UNEP) found that “since 1990, at least eighteen violent conflicts have been fueled by the exploitation of natural resources,” and that effective natural resource management is a necessary component of conflict prevention and peacebuilding operations.

The Elephant in the Room: Predicting the Arab Spring

Why did the Index fail to predict the Arab Spring sweeping the Middle East and North Africa? Many critics assert that the inconsistent ranking of the states, ranging from Yemen (ranked 13th) to Bahrain (ranked 129th), demonstrates that the Index is a poor indicator of state instability. Particularly, critics argue that many of the countries experiencing revolutions were ranked artificially low.

“Of course, the Failed States Index did not predict the Arab Spring, and nor is it intended to predict such upheavals,” said Messner at the launch event. “But by digging down deeper into the specific indicator analysis, it was possible to observe the growing tensions in those countries.” The Index has consistently highlighted specific troubling indicators for the region, such as severe demographic pressures, migration, group grievance, human rights, state legitimacy, and political elitism.

Blake Hounshell, a correspondent with Foreign Policy (long-time collaborators with the Fund for Peace on the Index), wrote that the Index was never meant to be a “crystal ball” – even the best statistical data cannot truly encapsulate the complex realities that lead to inherently unpredictable events, such as revolutions. “It’s thousands of individual decisions, not rows of statistics, that add up to political upheaval,” Hounshell continued.

Demographer Richard Cincotta’s work on Tunisia’s revolution illuminates how the Index’s linear indicators can mask a complex reality. Whereas the Failed States Index simply measures “demographic pressure” as a linear function of how youthful a population is, Cincotta pointed out at a Wilson Center event that it was actually Tunisia’s relative demographic maturity that paved the way for its revolution and gives it a good chance of achieving a liberal democracy. Other countries in the region are much younger than Tunisia (Yemen being the youngest). The Arab Spring demonstrates that static indicators alone often do not have the capacity to predict complex social and political revolutions.

Sources: Foreign Policy, The Fund for Peace, UNEP.

Image Credit: Failed States Index 2011, Foreign Policy. -

Watch: Michael Renner on Creating Peacebuilding Opportunities From Disasters

›Michael Renner is a senior researcher at the Worldwatch Institute working on the intersection between environmental degradation, natural resource issues, and peace and conflict. Recently, Renner has focused on water use and its effects on the Himalayan region. In particular he’s working to find positive opportunities that can turn “what is a tremendous problem, into perhaps an opportunity for collaboration among different communities, among different regions, and perhaps…ultimately across the borders of the region,” he said during this interview with ECSP.

-

Preparing for the Impact of a Changing Climate on U.S. Humanitarian and Disaster Response

›Climate-related disasters could significantly impact military and civilian humanitarian response systems, so “an ounce of prevention now is worth a pound of cure in the future,” said CNA analyst E.D. McGrady at the Wilson Center launch of An Ounce of Preparation: Preparing for the Impact of a Changing Climate on U.S. Humanitarian and Disaster Response. The report, jointly published by CNA and Oxfam America, examines how climate change could affect the risk of natural disasters and U.S. government’s response to humanitarian emergencies. [Video Below]

Connecting the Dots Between Climate Change, Disaster Relief, and Security

The frequency of – and costs associated with – natural disasters are rising in part due to climate change, said McGrady, particularly for complex emergencies with underlying social, economic, or political problems, an overwhelming percentage of which occur in the developing world. In addition to the prospect of more intense storms and changing weather patterns, “economic and social stresses from agricultural disruption and [human] migration” will place an additional burden on already marginalized communities, he said.

Paul O’Brien, vice president for policy and campaigns at Oxfam America said the humanitarian assistance community needs to galvanize the American public and help them “connect the dots” between climate change, disaster relief, and security.

As a “threat multiplier,” climate change will likely exacerbate existing threats to natural and human systems, such as water scarcity, food insecurity, and global health deterioration, said Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, USN (ret.), president of CNA’s Institute for Public Research. Major General Richard Engel, USAF (ret.), of the National Intelligence Council identified shifting disease patterns and infrastructural damage as other potential security threats that could be exacerbated by climate change.

“We must fight disease, fight hunger, and help people overcome the environments which they face,” said Gunn. “Desperation and hopelessness are…the breeding ground for fanaticism.”

U.S. Response: Civilian and Military Efforts

The United States plays a very significant role in global humanitarian assistance, “typically providing 40 to 50 percent of resources in a given year,” said Marc Cohen, senior researcher on humanitarian policy and climate change at Oxfam America.

The civilian sector provides the majority of U.S. humanitarian assistance, said Cohen, including the USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. These organizations provide leadership, funding, and food aid to developing countries in times of crisis, but also beforehand: “The internal rationale [of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance] is to reduce risk and increase the resilience of people to reduce the need for humanitarian assistance in the future,” said Edward Carr, climate change coordinator at USAID’s Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance.

The U.S. military complements and strengthens civilian humanitarian assistance efforts by accessing areas that civilian teams cannot reach. The military can utilize its heavy lift capability, in-theater logistics, and command and control functions when transportation and communications infrastructures are impaired, said McGrady, and if the situation calls for it, they can also provide security. In addition, the military could share lessons learned from its considerable experience planning for complex, unanticipated contingencies with civilian agencies preparing for natural disasters.

“Forgotten Emergencies”

Already under enormous stress, humanitarian assistance and disaster response systems have persistent weaknesses, such as shortfalls in the amount and structure of funding, poor coordination, and lack of political gravitas, said Cohen.

Food-related aid is over-emphasized, said Cohen: “If we break down the shortfalls, we see that appeals for food aid get a better response than the type of response that would build assets and resilience…such as agricultural bolstering and public health measures.” Food aid often does not draw on local resources in developing countries, he said, which does little to improve long-term resilience.

“Assistance is not always based on need…but on short-term political considerations,” said Cohen, asserting that too much aid is supplied to areas such as Afghanistan and Iraq, while “forgotten emergencies,” such as the Niger food crisis, receive far too little. Furthermore, aid distribution needs to be carried out more carefully at the local scale as well: During complex emergencies in fragile states, any perception of unequal assistance has the potential to create “blowback” if the United States is identified with only one side of a conflict.

Engel added that many of the problems associated with humanitarian assistance will be further compounded by increasing urbanization, which concentrates people in areas that do not have adequate or resilient infrastructure for agriculture, water, or energy.

Preparing for Unknown Unknowns

A “whole of government approach” that utilizes the strengths of both the military and civilian humanitarian sectors is necessary to ensure that the United States is prepared for the future effects of climate change on complex emergencies in developing countries, said Engel.

In order to “cut long-term costs and avoid some of the worst outcomes,” the report recommends that the United States:

Cohen singled out “structural budget issues” that pit appropriations for protracted emergencies in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Darfur against unanticipated emergencies, like the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Disaster-risk reduction investments are not a “budgetary trick” to repackage disaster appropriations but a practical way to make more efficient use of current resources, he said: “Studies show that the return on disaster-risk reduction is about seven to one – a pretty good cost-benefit ratio.”- Increase the efficiency of aid delivery by changing the budgetary process;

- Reduce the demand by increasing the resilience of marginal (or close-to-marginal) societies now;

- Be given the legal authority to purchase food aid from local producers in developing countries to bolster delivery efficiency, support economic development, and build agricultural resilience;

- Establish OFDA as the single lead federal agency for disaster preparedness and response, in practice as well as theory;

- Hold an OFDA-led biannual humanitarian planning exercise that is focused in addressing key drivers of climate-related emergencies; and,

- Develop a policy framework on military involvement in humanitarian response.

Edward Carr said that OFDA is already integrating disaster-risk reduction into its other strengths, such as early warning systems, conflict management and mitigation, democracy and governance, and food aid. However, to build truly effective resilience, these efforts must be tied to larger issues, such as economic development and general climate adaptation, he said.

“What worries me most are not actually the things I do know, but the things we cannot predict right now,” said Carr. “These are the biggest challenges we face.”

“Pakistan Floods: thousands of houses destroyed, roads are submerged,” courtesy of flickr user Oxfam International. -

Vik Mohan, Rebecca Hill, and Alasdair Harris

In FOCUS: To Live With the Sea: Reproductive Health Care and Marine Conservation in Madagascar

›July 12, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffDownload FOCUS Issue 23: “To Live With the Sea: Reproductive Health Care and Marine Conservation in Madagascar,” from the Wilson Center.

Christine does not know how old she is. She has 16 children and lives on a remote island off the southwestern coast of Madagascar. She and her children, like other members of the Vezo ethnic group, depend entirely on the ocean for their survival. Her husband, a fisherman, struggles to catch enough to feed his family.

In this isolated area, most girls have their first child before the age of 18, and families with 10 children or more are commonplace. But since the marine conservation NGO Blue Ventures launched a family planning program in 2007, couples and women like Christine are able to make their own reproductive health choices.

Blue Ventures’ Vik Mohan, Rebecca Hill, and Alasdair Harris argue that their integrated approach, which combines reproductive health care and education with conservation and alternative livelihoods, offers these communities – and the marine environment on which they depend – the best possible chances of survival. -

Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

Double Choke Point: Demand for Energy Tests Water Supply and Economic Stability in China and the U.S.

›The original version of this article, by Keith Schneider, appeared on Circle of Blue.

The coal mines of Inner Mongolia, China, and the oil and gas fields of the northern Great Plains in the United States are separated by 11,200 kilometers (7,000 miles) of ocean and 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) of land.

But, in form and function, the two fossil fuel development zones – the newest and largest in both nations – are illustrations of the escalating clash between energy demand and freshwater supplies that confront the stability of the world’s two biggest economies. How each nation responds will profoundly influence energy prices, food production, and economic security not only in their domestic markets, but also across the globe.

Both energy zones require enormous quantities of water – to mine, process, and use coal; to drill, fracture, and release oil and natural gas from deep layers of shale. Both zones also occur in some of the driest regions in China and the United States. And both zones reflect national priorities on fossil fuel production that are causing prodigious damage to the environment and putting enormous upward pressure on energy prices and inflation in China and the United States, say economists and scholars.

“To what degree is China taking into account the rising cost of energy as a factor in rising overall prices in their economy?” David Fridley said in an interview with Circle of Blue. Fridley is a staff scientist in the China Energy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “What level of aggregate energy cost increases can China sustain before they tip over?”

“That’s where China’s next decade is heading – accommodating rising energy costs,” he added. “We’re already there in the United States. In 13 months, we’ll be fully in recession in this country; 9 percent of our GDP is energy costs. That’s higher than it’s been. When energy costs reach eight to nine percent of GDP, as they have in 2011, the economy is pushed into recession within a year.”

Continue reading on Circle of Blue.

Photo Credit: Used with permission, courtesy of J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue. In Ningxia Province, one of China’s largest coal producers, supplies of water to farmers have been cut 30 percent since 2008. -

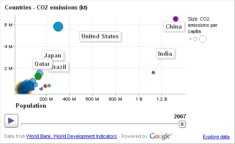

Consumption and Global Growth: How Much Does Population Contribute to Carbon Emissions?

›July 6, 2011 // By Schuyler Null When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

In Prosperity Without Growth, first published by the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission and later by EarthScan as a book, economist Tim Jackson writes that it is “delusional” to rely on capitalism to transition to a “sustainable economy.” Because a capitalist economy is so reliant on consumption and constant growth, he concludes that it is not possible for it to limit greenhouse gas emissions to only 450 parts per million by 2050.

It’s worth noting that the UN has updated its population projections since Jackson’s original article. The medium variant projection for average annual population growth between now and 2050 is now about 0.75 percent (up from 0.70). The high variant projection bumps that growth rate up to 1.08 percent and the low down to 0.40 percent.

Either way, though population may play a major role in the development of certain regions, it plays a much smaller role in global CO2 emissions. In a fairly exhaustive post, Andrew Pendleton from Political Climate breaks down the math of Jackson’s most interesting conclusions and questions, including the role of population. He writes that the larger question is what will happen with consumption levels and technological advances:The argument goes like this. Growth (or decline) in emissions depend by definition on the product of three things: population growth (numbers of people), growth in income per person ($/person), and on the carbon intensity of economic activity (kgCO2/$). This last measure depends crucially on technology, and shows how far growth has been “decoupled” from carbon emissions. If population growth and economic growth are both positive, then carbon intensity must shrink at a faster rate than the other two if we are to slash emissions sufficiently.

Pendleton also brings up the prickly question of global inequity and how that impacts Jackson’s long-term assumptions:

Jackson calculates that to reach the 450 ppm stabilization target, carbon emissions would have to fall from today’s levels at an average rate of 4.9 percent a year every year to 2050. So overall, carbon intensity has to fall enough to get emissions down by that amount and offset population and income growth. Between now and 2050, population is expected to grow at an average of 0.7 percent and Jackson first considers an extrapolation of the rate of global economic growth since 1990 – 1.4 percent a year – into the future. Thus, to reach the target, carbon intensity will have to fall at an average rate of 4.9 + 0.7 + 1.4 = 7.0 percent a year every year between now and 2050. This is about 10 times the historic rate since 1990.

Pause at this stage, and take note that if there were no further economic growth, carbon intensity would still have to fall at a rate of 4.9 + 0.7 = 5.6 percent, or about eight times the rate over the last 20 years. To his credit, Jackson acknowledges this – as he puts it, decoupling is vital, with or without growth. Decoupling will require both huge innovation and investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon energy technologies. One question, to which we’ll return later, is whether and how you can get this if there is no economic growth.But Jackson doesn’t stop there. He goes on to point out that taking historical economic growth as a basis for the future means you accept a very unequal world. If we are serious about fairness, and poor countries catching up with rich countries, then the challenge is much, much bigger. In a scenario where all countries enjoy an income comparable with the European Union average by 2050 (taking into account 2.0 percent annual growth in that average between now and 2050 as well), then the numbers for the required rate of decoupling look like this: 4.9 percent a year cut in carbon emissions + 0.7 percent a year to offset population growth + 5.6 percent a year to offset economic growth = 11.2 percent per year, or about 15 times the historical rate.

To further complicate how population figures into all this, Brian O’Neill’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences article, “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions,” shows that urbanization and aging trends will have differential – and potentially offsetting – impacts on carbon emissions. Aging, particularly in industrialized countries, will reduce carbon emissions by up to 20 percent in the long term. On the other hand, urbanization, particularly in developing countries, could increase emissions by 25 percent.

What do you think? Is infinite growth possible? If so, how do you reconcile that with its effects on “spaceship Earth?” Do you rely on technology to improve efficiency? Do you call it a loss and hope the benefits of growth are worth it?

Sources: Political Climate, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Prosperity Without Growth (Jackson). -

Nepal to East Africa: Population, Health, and Environment Programs Compared

›“Practice, Harvest and Exchange: Exploring and Mapping the Global, Health, Environment (PHE) Network of Practice,” by the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Institute and the USAID-supported BALANCED Project, explores the successes and challenges of their global population, health, and environment (PHE) network (with a heavy presence in East Africa). In order to increase support of the nascent PHE approach, the network seeks to shorten the “collaborative distance” between “PHE champions,” so they can develop a stronger body of evidence for the links between population, health, and the environment. In their analysis, the authors write that the network has facilitated the development of independent, information-sharing relationships between “champions.” However, they also observed shortfalls in the network, such as its limited reach into less technologically advanced yet more biodiverse regions, its bias toward BALANCED meet-up event participants, and its exclusion of those experts unlikely to be included in published works. In “Linking Population, Health, and the Environment: An Overview of Integrated Programs and a Case Study in Nepal” from the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Sigrid Hahn, Natasha Anandaraja, and Leona D’Agnes provide both a broad survey of the structure and content of programs using the PHE method and an in-depth case study of a successful initiative in Nepal. Hahn et al. praise the Nepalese program for simultaneously addressing deforestation from fuel-wood harvesting, indoor air pollution from wood fires, acute respiratory infections related to smoke inhalation, as well as family planning in Nepal’s densely populated forest corridors. “The population, health, and environment approach can be an effective method for achieving sustainable development and meeting both conservation and health objectives,” the authors conclude. In particular, one benefit of cross-sectoral natural resource and development programs is the inclusion of men and adolescent boys typically overlooked by strictly family planning programs.

In “Linking Population, Health, and the Environment: An Overview of Integrated Programs and a Case Study in Nepal” from the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Sigrid Hahn, Natasha Anandaraja, and Leona D’Agnes provide both a broad survey of the structure and content of programs using the PHE method and an in-depth case study of a successful initiative in Nepal. Hahn et al. praise the Nepalese program for simultaneously addressing deforestation from fuel-wood harvesting, indoor air pollution from wood fires, acute respiratory infections related to smoke inhalation, as well as family planning in Nepal’s densely populated forest corridors. “The population, health, and environment approach can be an effective method for achieving sustainable development and meeting both conservation and health objectives,” the authors conclude. In particular, one benefit of cross-sectoral natural resource and development programs is the inclusion of men and adolescent boys typically overlooked by strictly family planning programs.