Showing posts from category climate change.

-

‘Watch Live: September 2, 2010’ Integrated Analysis for Development and Security: Scarcity and Climate, Population, and Natural Resources

›September 2, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffEnvironmental Change and Security Program

Thursday, September 2, 2010, 12:00 p.m. – 2:00 p.m

Woodrow Wilson Center, Washington DC

Event is invitation only. Please tune into the live webcast, which will begin at approximately 12:10 p.m.

Agenda Webcast

Alex Evans, Head of Program, Climate Change, Resource Scarcity and Multilateralism, Center on International Cooperation, New York University; Writer and Editor, Global Dashboard

Mathew J. Burrows, Counselor and Director, Analysis and Production Staff, National Intelligence Council (NIC)

Geoffrey D. Dabelko (Moderator), Director, Environmental Change and Security Program, Woodrow Wilson Center

Alex Evans thinks energy, climate, food, natural resources, and population trends are mistakenly considered separate challenges with a few shared attributes. He suggests instead that scarcity provides a frame for tying these sectors together and better understanding the collective implications for development and security. As a regular advisor to the United Nations and national governments, Evans will outline practical policy conclusions that flow from a focus on scarcity and integrated analysis.

As counselor and director of the analysis and production staff, Mathew J. Burrows manages a staff of senior analysts and production technicians who guide and shepherd all NIC products from inception to dissemination. He was the principal drafter for the NIC publication, “Global Trends 2025: A Transformed World,” the NIC’s flagship, long-range integrated analysis assessment that prominently featured natural resource, climate, and demographic trends. Burrows will share insights on producing and presenting integrated analysis for practitioners and policymakers.

Note: The live webcast will begin approximately 10 minutes after the posted meeting time and an archived version will be available on the Wilson Center website in the future. You will need Windows Media Player to watch the webcast. To download the free player, please visit: http://www.microsoft.com/windows/windowsmedia/download. -

The Complexities of Decarbonizing China’s Power Sector

›August 27, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffOver the past year, there have been a series of new initiatives on U.S.-China energy cooperation. These initiatives have focused primarily on low-carbon development, and have covered everything from renewables and energy efficiency to clean vehicles and carbon capture and storage. Central to the long-term success of these efforts will be strengthening the U.S.’s incomplete understanding of China’s electricity grid, as all of the above issues are inextricably linked to the power grid itself.

As both the United States and China try to figure out how to decarbonize their power sectors with a mixture of policy reform and infrastructure development, China’s power-sector reforms could present valuable lessons for the United States. At a China Environment Forum meeting earlier this summer, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Chairman Jon Wellinghoff joined power sector experts Jim Williams, Fritz Kahrl, and Ding Jianhua from Energy and Environmental Economics (E3) to address the subject, discussing gaps related to electricity sector analysis and presenting research on decarbonizing China’s electricity sector.

Addressing Shared Challenges

Chairman Wellinghoff kicked off the presentation with an overview of the similarities and differences in the U.S. and Chinese power sectors. Wellinghoff stressed that both countries face common obstacles in expanding renewables, namely that wind- and solar-energy sources are located inland, far away from booming coastal cities where energy demand is highest. He added that market and regulatory incentives to integrate renewables into grids are currently insufficient.

However, Wellinghoff also made the point that each side has comparative advantages. For instance, while China has superior high-voltage grid transmission technologies, the United States has been developing advanced demand-side management practices and markets to spur energy efficiency and renewable integration in the power sector. Wellinghoff argued that mutual understanding of each others’ power sectors is important for trust-building and effective cooperation, and can result in net climate and economic benefits for both sides.

Achieving these benefits will not be easy. E3’s Jim Williams noted that the Chinese power sector is currently in transition, a process that is producing some increasingly complicated policy questions. How these questions are answered has the potential to drastically shift the outlook for China’s carbon emissions. For instance, if the United States can help push China’s power sector to become less carbon-intensive, there could be substantial benefits for lowering global greenhouse gas emissions.

One of the major issues at the moment is assessing the cost-benefit analysis of renewable and low-carbon integration and trying to ascertain what the actual cost of decarbonizing the power sector would be. Due to a lack of “soft technology” — analytical methods, software models, institutional processes, and the like — policymakers in China still do not have a good sense of what level of greenhouse gas reductions could be achieved in the power sector for a given cost.

More Intensive Research Needed

Fritz Kahrl and Ding Jianhua, also from E3, went on to explain that for China, as with the United States, the underlying issues of how to decarbonize the power sector will demand considerable quantitative analysis. The United States has more than three decades of experience with quantitative policy analysis in the power sector, driven in large part by regulatory processes that require cost-benefit analysis. In China, policy analysis in the power sector is still at an early stage, but there is an increasing demand among policymakers for this kind of information.

For instance, over the past five years, China’s government has allocated significant amounts of money and attention to energy efficiency. However, standardized tools to assess the benefits and costs of energy efficiency projects are not widely used in China, which has led to a lack of transparency and accountability in how energy efficiency funds are spent. This problem is increasingly recognized by senior-level decision-makers. Drawing from its own experience, the United States could play an important role in helping Chinese analysts develop quantitative approaches for power sector policy analysis.

Pete Marsters is project assistant with the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: “Coal Power Plant (China),” courtesy of flickr user ishmatt. -

Derek S. Reveron, The New Atlanticist

When National Security Overlaps With Human Security

›August 24, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article appeared on the Atlantic Council’s New Atlanticist blog. By Derek S. Reveron.

For the second time this year, naval forces have been involved in major operations that have little to do with combat at sea. Instead, Sailors and Marines operating from dozens of warships have responded to natural disasters.

Earlier this year in Haiti, traditional warships delivered food, water, and medical supplies. On amphibious ships, the large flight decks designed to move Marines ashore via helicopters proved to be temporary airports for search and rescue teams; medical facilities designed to treat wounded infantry became floating clinics for sick and injured civilians. The use of naval ships as airports, hospitals, or as refugee camps must be temporary, but in a crisis, temporary relief is what is necessary.

Similar uses of militaries are occurring in response to flooding in Pakistan and wildfires in Russia today. NATO is planning and executing responses to alleviate human suffering created by natural disasters, which are certainly non-traditional.

But militaries around the world are being called to serve their people and others in distress. Increasingly, militaries are including humanitarian assistance and disaster relief as a core concept in how they train, equip, and organize. Militaries have reluctantly embraced these new roles because their governments expect them to provide responses to humanitarian crises, support new partners, and reduce underlying conditions that give rise to instability.

At the same time that military aircrews rescue stranded people or military engineers erect temporary housing, critics worry that development is being militarized. But, they miss the larger point that military equipment like helicopters, medical facilities, and logistic hubs are necessary for providing humanitarian assistance during a crisis. Additionally, NGOs increasingly partner with militaries in North America and Europe because militaries have the capacity to reach populations in need where NGOs can deliver their services.

Given the real stress on militaries created by operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, these non-traditional operations are not needed to prove relevance for militaries in a difficult fiscal period. Instead, the inclusion of humanitarian assistance in military doctrine are driven by countries’ national strategies that increasingly link human security and national security. As I wrote in Exporting Security: International Engagement, Security Cooperation, and the Changing Face of the U.S. Military, militaries are being directed to be involved in humanitarian operations.

Far from preparation for major war, humanitarian activities rely on a unique blend of charitable political culture, latent civil-military capacity, and ambitious military officers who see the strategic landscape characterized by challenges to human security, weak states, and transnational actors. Further, changes are informed by international partners that conceive of their militaries as forces for good and not simply combat forces. The United States has been slow to catch up to European governments that see the decline of coercive power and the importance of soft power today.

This change is not only about the state of relations among governments today, but also the priority of human security. Security concerns over the last twenty years have been shifting away from state-focused traditional challenges to human-centered security issues such as disease, poverty, and crime. This is reflected in the diversity of ways by which NATO countries protect their national security. While there are remnants of Cold War conflicts on the Korean Peninsula and in the Persian Gulf region, these are largely the exception. Instead, sub-national and transnational challenges increasingly occupy national security professionals.

Within the United States, the government has embarked on a program to illustrate that its military superpower capabilities can be used for good. The same capability that can accurately drop a bomb on an adversary’s barracks has been used to deliver food aid in the mountains of Afghanistan. The same capability used to disembark Marines from Navy ships to a foreign shore have been used to host NGOs providing fisheries conservation in West Africa. And the same capability to track an enemy’s submarines can detect changes in the migration of fish stocks in response to climate change. To be sure, swords haven’t been beaten into plowshares, but military capabilities once used for confrontation are now used for cooperation.

Derek S. Reveron, an Atlantic Council contributing editor, is a Professor of National Security Affairs and the EMC Informationist Chair at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island.The views expressedare his own and do not reflect those of the Navy or the U.S. government.

Photo Credit: “100304-F-2616H-060” courtesy of flickr user Kenny Holston 21. -

“All Consuming:” U of M’s ‘Momentum’ on Population, Health, Environment, and More

›August 23, 2010 // By Schuyler NullMinnesota’s Institute on the Environment is only in its third year of operation but has already established itself as an emerging forum for population, health, and, environment issues, due in no small part to its excellent thrice-a-year publication, Momentum. The journal is not only chock-full of high production values and impressively nuanced stories on today’s global problems, but is also, amazingly, available for free.

Momentum has so far covered issues ranging from food security, gender equity, demographic change, geoengineering, climate change, life without oil, and sustainable development.

Highlights from the latest issue include: “Girl Empower,” by Emily Sohn; “Bomb Squad,” with Paul Ehrlich, Bjørn Lomborg, and Hans Rosling; and “Population Hero,” on the fiscal realities of stabilizing growth rates.

The lead story featured below, “All Consuming,” by David Biello, focuses on the debate over whether consumption or population growth poses a bigger threat to global sustainability.Two German Shepherds kept as pets in Europe or the U.S. use more resources in a year than the average person living in Bangladesh. The world’s richest 500 million people produce half of global carbon dioxide emissions, while the poorest 3 billion emit just 7 percent. Industrial tree-cutting is now responsible for the majority of the 13 million hectares of forest lost to fire or the blade each year — surpassing the smaller-scale footprints of subsistence farmers who leave behind long, narrow swaths of cleared land, so-called “fish bones.”

Continue reading on Momentum.

In fact, urban population growth and agricultural exports drive deforestation more than overall population growth, according to new research from geographer Ruth DeFries of Columbia University and her colleagues. In other words, the increasing urbanization of the developing world — as well as an ongoing increase in consumption in the developed world for products that have an impact on forests, whether furniture, shoe leather, or chicken fed on soy meal — is driving deforestation, rather than containing it as populations leave rural areas to concentrate in booming megalopolises.

So are the world’s environmental ills really a result of the burgeoning number of humans on the planet — growing by more than 150 people a minute and predicted by the United Nations to reach at least 9 billion people by 2050? Or are they more due to the fact that, while human population doubled in the past 50 years, we increased our use of resources fourfold?

Photo Credit: “All Consuming” courtesy of Momentum. -

Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in the Agricultural Sector

›“Climate Change and China’s Agricultural Sector: An Overview of Impacts, Adaptation and Mitigation” from the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) explores mitigation and adaptation strategies to avoid the worst effects of climate change in China’s farming sector. The authors, Jinxia Wang, Jikun Huang and Scott Rozelle, point out that, although often overlooked in favor of the industrial sector, a disproportionate amount (greater than 15 percent) of China’s greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture. Challenges include over-fertilization, high methane levels, water pollution, and water scarcity. Wang, Huan, and Rozelle predict that trade “can and should be used to help China mitigate the impacts of climate change” and programs promoting better calibration of fertilizer dosages and “conservation tilling” practices will help farmers reduce emissions.

Also from ICTSD comes another study on climate adaptation and mitigation, this time focusing on the developing world. Globally, agriculture accounts for only 4 percent of GDP but according to the IPCC it also accounts for more than 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, making climate adaptation and mitigation in the sector particularly important. “Agricultural Technologies for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Developing Countries: Policy Options for Innovation and Technology Diffusion” by Travis Lybbert and Daniel Sumner examines some of the more promising innovations that may help those countries most vulnerable to climate change to cope with and minimize risk. The authors suggest that most policies that target economic development and poverty reduction will also naturally lead to improvements in agriculture, accordingly most of their recommendations center around improving market efficiency, communication of technologies and best practices, and investment in research and development. -

Floods, Fire, Landslides, and Drought: The Guardian’s “Weather Crisis 2010”

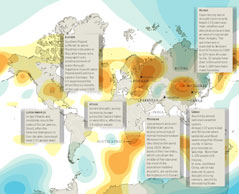

› From the Guardian’s DataBlog comes an excellent overview of some of the extreme weather affecting the globe this summer, from the devastating floods in Pakistan which have inflicted “huge losses” to crops and exacerbated an already tenuous security situation, to the wildfires in Russia which have smothered the capital in dangerous smog and crippled domestic wheat supplies.

From the Guardian’s DataBlog comes an excellent overview of some of the extreme weather affecting the globe this summer, from the devastating floods in Pakistan which have inflicted “huge losses” to crops and exacerbated an already tenuous security situation, to the wildfires in Russia which have smothered the capital in dangerous smog and crippled domestic wheat supplies.

“Global temperatures in the first half of the year were the hottest since records began more than a century ago,” writes author and graphic artist Mark McCormick.

The orange areas of the map represent high pressure systems and the blue, low pressure systems, which as explained by Peter Stott of the Met Office, are important indicators of the rare climatic conditions that caused this summer’s abnormal conditions across Eurasia.

The flooding in Pakistan has garnered the most international attention, having now affected more people than the 2004 tsunami, 2010 Haiti earthquake, and 2005 Kashmir earthquake combined. Other highlighted areas of the map include flooding in Poland and Germany, drought in England, mudslides in Latin and South America, record-breaking drought and hunger in West Africa, and flooding and landslides in China, which recently pushed the world’s largest hydroelectric dam to its limit and have now been blamed for more than 1,000 deaths.

Although it does a good job highlighting the frequency and severity of extreme weather events this summer, it’s important to note that the map only covers events in July and August. That leaves out the “1000-year” floods in Tennessee this May as well as the heavy snowfall seen in the Northeast United States and the winter of “white death” in Mongolia earlier this year, which also severely disrupted local and national infrastructure as well as a great many people’s livelihoods.

Sources: Agence France-Presse, BBC, Guardian, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, New York Times, Telegraph, UN Dispatch.

Image Credit: “Weather Crisis 2010” by Mark McCormick, courtesy of Scribd user smfrogers and The Guardian. -

Interview With Wilson Center’s Maria Ivanova: Engaging Civil Society in Global Environmental Governance

›August 13, 2010 // By Russell SticklorFrom left to right, the five consecutive Executive Directors of the United Nations Environment Programme: Achim Steiner, Klaus Toepfer, Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Mostafa Tolba, and Maurice Strong, at the 2009 Global Environmental Governance Forum in Glion, Switzerland.

In the eyes of much of the world, global environmental governance remains a somewhat abstract concept, lacking a strong international institutional framework to push it forward. Slowly but surely, however, momentum has started to build behind the idea in recent years. One of the main reasons has been the growing involvement of civil society groups, which have demanded a more substantial role in the design and execution of environmental policy—and there are signs that environmental leaders at the international level are listening.

On the heels of the UN Environment Programme’s Governing Council meeting earlier this year in Bali, a call was put out to strengthen the involvement of civil society organizations in the current environmental governance reform process. To that end, UNEP is creating a Civil Society Advisory Group on International Environmental Governance, which will act as an information-sharing intermediary between civil society groups and regional and global environmental policymaking bodies over the next few years. (The application deadline has been extended; applicants interested in joining the Advisory Group should submit their materials via e-mail by Sunday, August 15, 2010—full instructions are listed at the end of this post.)

Maria Ivanova, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and director of the Global Environmental Governance Project, played a key role in ensuring civil society engagement in the contemporary political process on international environmental governance reform. Ivanova recently sat down with the New Security Beat to talk about the future prospects for global environmental governance, the Rio+20 Earth Summit in Brazil in 2012, and how to foster a more open and sustained dialogue between the worlds of environmental policymaking and academia.

New Security Beat: What are the pitfalls of a regional approach to addressing climate change and other environmental issues, as opposed to an international approach?

Maria Ivanova: Global environmental problems cannot be solved by one country or one region alone, and require a collective global response. But they can also not be addressed solely at the global level because they require action by individuals and organizations in particular geographies. The conundrum with climate change is that the countries and regions most affected are the ones least responsible for causing the problem in the first case. We cannot therefore simply substitute a national or regional response for a global action plan, as more often than not, it would be a case of “victim pays” rather than “polluter pays”—the fundamental principle of environmental policy in the United States and most other countries. Importantly, however, our global environmental institutions do not possess the requisite authority and ability to enforce agreements and sanction non-compliance.

NSB: What are some of the inherent difficulties in getting countries to see eye-to-eye and collaborate on the development of institutions for global environmental governance?

MI: The most important difficulty is perhaps the lack of trust and a common ethical paradigm accompanied by a pervasive suspicion about countries’ motives. Secondly, there is a perceived dichotomy between environment and development that has lodged in the consciousness of societies around the world. Thirdly, there’s the inability of current institutions to deliver on existing commitments. The resulting blame game feeds suspicions and restarts the whole cycle again.

NSB: Do you see the 21st century’s various environmental challenges as being a driver of international conflict or cooperation?

MI: After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was expected that global environmental (and other) issues would be a driver for cooperation. A green dividend was expected, and the 1992 Rio Earth Summit fostered much hope. But quite the opposite happened. Global environmental challenges such as climate change, for example, have caused more conflict than cooperation. Other concerns, such as whaling and biodiversity loss, have also triggered conflicts as governments have become fiercely protective of their national sovereignty. On the other hand, civil society groups and even individuals around the world have come together in new coalitions and formed new alliances. So while at a governmental level we observe increased tension, at a civil society level, we witness unprecedented mobilization and collaboration, especially through social media. Obviously, we live in a new world.

NSB: There has been a lot of talk about bridging the gap between the academic and policy worlds—two communities that do not typically have much interaction, but likely have a lot to learn from one another. What steps do you think can be taken regarding environmental governance that might facilitate a sustained dialogue and interaction between the two sides?

MI: Many academics have thought, debated, and written about global environmental governance. Fewer have presented their analysis to policymakers and politicians. At the Global Environmental Governance (GEG) Project that I direct, we seek to bridge that gap and provide a clearinghouse of information, serving as a “brutal analyst,” and acting as an honest broker among various groups working in this field. Moreover, we are in the process of launching a collaborative initiative among the Global Environmental Governance Project, the Center for Law and Global Affairs at Arizona State University, and the Academic Council on the UN System to collect, compile, and communicate academic thinking on options for reform to the ongoing political process on international environmental governance. We are creating a Linked-In group where we hope to engage in discussions with colleagues from universities around the world with the purpose of generating ideas, developing options, and testing them with policymakers. Moreover, we are engaging with civil society beyond academia. The GEG Project is sponsoring five regional events on governance in Argentina, China, Ethiopia, Nepal, and Uganda that are taking place in August and September. Led by young environmental leaders in those countries who attended the 2009 Global Environmental Governance Forum in Glion, Switzerland, these consultations are generating genuine engagement in thought and action on governance. So, new initiatives are certainly emerging and the results could be visible by the Rio+20 conference in May 2012.

NSB: What are your expectations for Rio+20?

MI: Given that governance is a major issue on the agenda for Rio+20, my hope is that the conference will bring about a new model for global governance, which reframes the environment-development dichotomy, cultivates shared values, and fosters leadership. Indeed, I am convinced that leadership is the most important necessary condition for change. We need to encourage more bold, visionary, entrepreneurial behavior rather than conformity.

My hidden hope for Rio+20 is that it will dramatically shift the narrative and move us from sustainable development to sustainability. Sustainability builds on sustainable development but goes further than that. As a concept it allows for new thinking, new actors, and new politics. It avoids the North-South polarization of sustainable development, which is so often equated with development and is therefore understood as what the North has already attained and what the South is aspiring to. By contrast, no one society has reached sustainability, and learning by all is necessary. Moreover, much of the innovative thinking about sustainability is happening in developing countries, which are trying to improve quality of life without jeopardizing the carrying capacity of the environment. Progressive thinking is also taking place on campuses in industrialized countries, which are creating a new sense of community and collaboration. Indeed, young people around the world are engaging in finding new ways of living within the planetary limits in a responsible and fulfilling manner.

Maria Ivanova is director of the Global Environmental Governance Project, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and an assistant professor of global governance at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston.

If you wish to nominate yourself or someone else as a candidate for the Civil Society Advisory Group on IEG, you need to submit materials to civil.society@unep.org by Sunday, August 15, 2010 (please copy info@environmentalgovernance.org). You can find the nomination form and the Terms of Reference for the group at the Global Environmental Governance Project’s website.

Photo Credit: “UNEP Leadership,” courtesy of the Global Environmental Governance Project. -

‘UK Royal Society: Call for Submissions’ “People and the Planet” Study To Examine Population, Environment, Development Links

›August 12, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffBy Marie Rumsby of the Royal Society’s In Verba blog.

In the years that followed the Iranian revolution, when Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile to Tehran and the country went to war against Iraq, the women of Iran were called upon to provide the next generation of soldiers. Following the war the country’s fertility rate fell from an average of over seven children per woman to around 1.7 children per woman – one of the fastest falls in fertility rates recorded over the last 25 years.

Iran is an interesting example but every country has its own story to tell when it comes to population levels and rates of change. The global population is rising and is set to hit 9 billion by 2050. And whilst fertility rates in Ethiopia are on the decline, its total population is projected to double from around 80 million today, to 160 million in 2050.

Earlier this month, the Royal Society announced it is undertaking a new study which will look at the role of global population in sustainable development. “People and the Planet” will investigate how population variables – such as fertility, mortality, ageing, urbanization, and migration – will be affected by economies, environments, societies, and cultures, over the next 40 years and beyond.

The group informing the study is chaired by Nobel Laureate Sir John Sulston FRS, and includes experts from a range of disciplines, from all over the world. With names on the group such as Professor Demissie Habte (President of the Ethiopian Academy of Sciences), Professor Alastair Fitter FRS (Professor Environmental Sciences, University of York) and Professor John Cleland FBA (Professor of Medical Demography, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine), there’s bound to be some lively discussions.

Linked to the announcement of the study, the Society held a PolicyLab with Fred Pearce, environmental journalist, and Jonathon Porritt, co-founder of Forum for the Future, to discuss the significance of population in sustainable development.

Both speakers have been campaigning against over-consumption for many years. Jonathon Porritt has been a keen advocate for fully funded, fully engaged voluntary family planning in every country in the world that wants it.

“In my opinion, that would allow us to stabilize global population at closer to 8 billion, rather than 9 billion. And if we did it seriously for forty years, that is an achievable goal.” Porritt thinks that stabilizing global population at 8 billion rather than 9 billion would save a large number of women’s lives, and suggests “you cannot ignore the gap between 8 billion and 9 billion if you are thinking seriously about climate change.”

Fred Pearce acknowledges that population matters, but stresses that it is consumption (and how we produce what we produce) that we need to focus on. He feels it is too convenient for us to focus on population.

According to Fred, the global average is now 2.6 children per woman – that’s getting close to the global replacement level of 2.3 children per woman.

“It is no longer human numbers that are the main threat……It’s the world’s consumption patterns that we need to fix, not its reproductive habits,” said Pearce.

The Society will be taking a long look at some of these issues, assessing the latest scientific evidence and uncertainty around population levels and rates of change. The “People and the Planet” study is due for publication in early 2012, ahead of the Rio+20 UN Earth Summit. The Society is currently seeking evidence to inform this study from a wide-range of stakeholders.

The deadline for submissions is October 1, 2010. For more information on submissions, please see the Royal Society’s full call for evidence announcement.

Image Credit: “In Verba” courtesy of the Royal Society.