Showing posts from category climate change.

-

John Donnelly, Global Post

Reproductive Health’s Connection to Global Problems

›September 26, 2011 // By Wilson Center Staff The original version of this article, by John Donnelly, appeared on Global Post.

The original version of this article, by John Donnelly, appeared on Global Post.

At a forum at the Rubin Art Museum earlier this week, a group of global leaders, including two top U.S. officials, talked about how reproductive health issues for women were wrongly cast as only a women’s issue.

Instead, they said reproductive health was intimately connected to the world’s population boom, climate change, water and sanitation crises, economic downturns, educational rates, and development overall. And greater reproductive health rights would trigger a brighter future for the 600 million young women in the developing world, including the 10 million girls who are married before they reach the age 18, said the panelists, members of the Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health of Aspen Global Health and Development.

And yet, reproductive health and family planning is generally not a focus on the world stage. In fact, the topic is often avoided.

“If you can help young women feel empowered, where they themselves want to delay pregnancy, they can become the actors in their own lives,” Maria Otero, U.S. Under Secretary of State for Democracy and Global Affairs said at the Rubin Museum of Art. “What this Council allows us to do is think about the issue of reproductive health, one that is interconnected to all other issues” related to development.

Continue reading on Global Post.

Image Credit: “Age at 1st marriage (women),” courtesy of ChartsBin; data courtesy of Gapminder. -

Perfect Storm? Population Pressures, Natural Resource Constraints, and Climate Change in Bangladesh

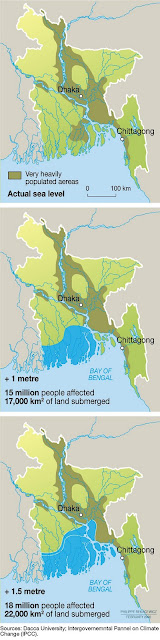

›Few nations are more at risk from climate change’s destructive effects than Bangladesh, a low-lying, lower-riparian, populous, impoverished, and natural disaster-prone nation. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that by 2050, sea levels in Bangladesh will have risen by two to three feet, obliterating a fifth of the country’s landmass and displacing at least 20 million people. On September 19, the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, with assistance from ECSP and the Comparative Urban Studies Project, hosted a conference that examined Bangladesh’s imperiled environmental security.

Climate Change and Population

The first panel focused on manifestations, drivers, and risks. Ali Riaz addressed the threat of climate refugees. Environmental stress, he said, may produce two possible responses: fight (civil conflict or external aggression) or flight (migration). In Bangladesh, the latter is the more likely outcome. Coastal communities, overwhelmed by rising sea levels and flooding, could migrate to Bangladesh’s urban areas or into neighboring India. Both scenarios pose challenges for the state, which already struggles to provide services to its urban masses and has shaky relations with New Delhi.

Mohamed Khalequzzaman examined Bangladesh’s geological vulnerability in the context of climate change. In a deltaic nation like Bangladesh, he explained, sedimentation levels must keep up with rates of sea level rise to prevent the nation from drowning. However, sediment levels now fall below 5 millimeters (mm) per year – short of the 6.5 mm Khalequzzaman calculates are necessary to keep pace with projected sea level rises. He lamented the nation’s tendency to construct large dams and embankments in the Bengal Delta, which “isolate coastal ecosystems from natural sedimentation,” he said, and result in lower land elevations relative to rising sea levels.

Adnan Morshed declared that Bangladesh’s geographic center – not its southern, flood-prone coastal regions – constitutes the nation’s chief climate change threat. Here, Dhaka’s urbanization is “destroying” Bangladesh’s environment, he said. Impelled by immense population growth (2,200 people enter Dhaka each day) and the need for land, people are occupying “vital wetlands” and rivers on the city’s eastern and western peripheries. “Manhattan-style” urban grid patterns now dominate wetlands and several rivers have become converted into land. Exacerbating this urbanization-driven environmental stress are highly polluting wetlands-based brickfields (necessary to satisfy Dhaka’s construction needs) and city vehicular gas emissions.

Adaptation Responses

The second panel considered possible responses to Bangladesh’s environmental security challenges. Roger-Mark De Souza trumpeted the imperative of more gender-inclusive policies. Environmental insecurity affects women and girls disproportionately, he said. When Bangladesh is stricken by floods, females must work harder to secure drinking water and to tend to the ill; they must often take off from school; and they face a heightened risk of sexual exploitation – due, in great part, to the lack of separate facilities for women in cyclone shelters. He reported that such conditions have often led to early forced marriages after cyclones.

Shamarukh Mohiuddin discussed possible U.S. responses. On the whole, American funding for global climate change adaptation programs has lagged and initiatives that are funded often focus more on short-term mitigation (such as emissions reductions) rather than adaptation. She recommended that Washington’s Bangladesh-based adaptation efforts be better coordinated with those of other donors.

Mohiuddin also suggested that to convey a greater sense of urgency, Bangladesh’s climate change threats should be more explicitly linked to national security – and particularly to how America’s strategic ally, India, would be affected by climate refugees fleeing Bangladesh.Philip J. DeCosse highlighted Bangladeshi government success stories in the famed Sundarbans – one of the world’s largest mangrove forests. Officials have banned commercial harvesting in some areas of the forests and shut down a highly polluting paper mill. He also praised civil society and the media for bringing attention to the Sundarban’s environmental vulnerability. As a result of efforts such as these, the Sundarbans are “coming back,” he said, with mangrove species growing anew. Thanks to a range of actors – from the forestry department to civil society – these forests are also now being “governed more than managed,” said DeCosse.

The Sundarbans – click to view larger map.

DeCosse’s fellow panelists identified additional hopeful signs. Morshed shared a photograph of a green, pristine park in Dhaka. De Souza underscored how family planning programs have worked in Bangladesh in the past, with fertility rates declining considerably in recent years, and several speakers spotlighted efforts by civil society and the media to bring greater attention to Bangladesh’s environmental security imperatives.

Nonetheless, major challenges remain, and panelists offered a panoply of recommendations. Khalequzzaman called for a major geological study of soil loss and siltation. De Souza implored Bangladesh to ensure that women’s roles and family planning considerations are featured in climate change negotiations and adaptation policies. Morshed advocated for imposing urban growth boundaries and enhancing public transport in cities. And several speakers spoke of the need to pursue more effective natural-resource-sharing arrangements with India. Ultimately, in the words of De Souza, it may not be possible to eliminate Bangladesh’s “perfect storm” – but much can be done to calm it.

Event ResourcesMichael Kugelman is a program associate with the Wilson Center’s Asia Program.

Sources: UN.

Photo/Image Credit: “Precarious Living, Dhaka,” courtesy of flickr user Michael Foley Photography; “Impact of Sea Level Rise in Bangladesh,” courtesy of UNEP; and the Sundarbans courtesy of Google Maps. -

Redrawing the Map of the World’s International River Basins

›Understanding why conflict over water resources arises between nations begins with a solid understanding of the geography of international river basins. Where are the basins? How big are they? How many people live there? Who are the riparian nations, and what is the significance of each to the basin?

-

IRP and TIME Collaborate on Indonesia’s Palm Oil Dilemma

›“Everything the company does goes against my conscience. But the question remains, who should work from the inside to inform everyone? Who should be pushing that these things are right, these things are acceptable, and these things are not?” says Victor Terran, in this video by Jacob Templin for TIME and the International Reporting Project (IRP). Templin traveled to Indonesia as part of IRP’s Gatekeeper Editor program in May 2011.

Terran is a resident of a village west of Borneo in the Kalimatan province, where he works as a field supervisor for one of the largest palm oil companies in Indonesia. Although the industry has supplied his village with much-needed employment and economic development, he worries that the influx of jobs has come at the expense of the health of the forests, agriculture, and clean rivers that sustain his village. “It’s not just about the money,” he says. “Will they sincerely keep the regulations and be fair to our community?”

An Industry with a Checkered Past

Terran’s skepticism of the industry is justified – palm companies, such as Sinar Mas, have a nasty track record of “abusing local labor and pilfering forests” for what they call “liquid gold,” says Templin.

Greenpeace released a report, “How Sinar Mas is Pulping the Planet,” in 2010 that alleged that Sinar Mas cut down important wildlife preserves, illegally planted on peat lands, and that these actions resulted in the release of considerable amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and loss of critical wildlife habitat.

As a result, the company lost major contracts with Unilever, Kraft, and Nestle. Sinar Mas CEO Franky Widjaya tells Templin that the company is taking definitive steps to prevent such instances from happening again, but that change will not happen overnight.

Akhir bin Man, a manager for another palm oil company, PT Kal, says he does not want to experience a public relations nightmare similar to Sinar Mas, so his company is seeking certification from the internationally recognized Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). The RSPO certification requires PT Kal to conserve nearly half of its land, use safer pesticides, and negotiate profit-sharing agreements with villagers.

Global Benefits

“These are not only vast forest landscapes which are home to species such as orangutans, elephants, and rhinos, but they’re also some of the globally most important reservoirs of carbon,” Adam Tomasek, director of the WWF Heart of Borneo Initiative, tells Templin.

Due to the wide-scale implications of disrupting such a substantial carbon sink, Tomasek and his colleagues see the destruction of these habitats as not just a local problem: “Sustainably managing the forest and carbon stocks that they contain here in Indonesia is not only important locally, not only important regionally, but an extremely important critical in the global approach to dealing with climate change,” he says.

Resisting the Juggernaut

Recognizing the inherent value of their natural resources, some villages are fighting to keep palm companies off of their land. Pak Bastarian is the head of such a village: “In my opinion, [palm] plantations are only owned by certain groups of people, and they don’t necessarily bring prosperity,” he tells Templin.

Bastarian is a reformed environmentalist whose hesitance toward the palm industry is a by-product of his own experiences – in the 1990s he worked for years running a timber company that illegally cut down trees. “I don’t know how many trees I cut down…a countless number.” Now, he uses his elected power to preserve trees like the ones he once cut down.

However, keeping the companies out of his village is an uphill battle, Templin explains. Bastarian says he faces mounting pressure from governmental officials, who make threats, and many villagers, who would rather have the jobs. He tells Templin that he even received bribes from PT Kal (an accusation they deny).

Bastarian’s position may cost him though – with elections right around the corner, he said does not know how much longer he can keep the palm companies out.

“My worry is that if our forests are cleared, our children will not be able to see what protected wood looks like, or what protected animals look like,” he tells Templin. When the palm oil companies first came, he chose to wait and see how the other villages fared before allowing them to come in. “To this day,” he says, “I’ve never changed my mind.”

Video Credit: “Indonesia’s Palm Oil Dilemma: To Cash In or Fight for the Forests?,” courtesy of the International Reporting Project. -

Laurie Mazur, RH Reality Check

Why Women’s Rights Are Key to Thriving in the Age of the “Black Swan”

›August 16, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Laurie Mazur, appeared on the RH Reality Check blog.

Welcome to the age of the “black swan.”

The tornado that nearly leveled the city of Joplin, Missouri in May was a black swan; so was the 9.0 magnitude earthquake and tsunami that rocked Japan in March; and the “hundred-year floods” that now take place every couple of years in the American Midwest.

A black swan is a low-probability, high-impact event that tears at the very fabric of civilization. And they are becoming more common: Weather-related disasters spiked in 2010, killing nearly 300,000 people and costing $130 billion.

Black swan events are proliferating for many reasons – notably climate change and the growing scale and interconnectedness of the human enterprise. World population doubled in the last half-century to just under seven billion people, so there are simply more people living in harm’s way, on geologic faults and along vulnerable coastlines. As the human enterprise has grown, we have reshaped natural systems to meet human needs, weakening resilience of ecosystems, and by extension our own. In effect, we have re-engineered the planet and ushered in a new era of radical instability.

At the same time, the world’s people are increasingly linked by systems of staggering complexity and size: think of electrical grids and financial markets. What were once local disasters now reverberate across the globe.

So what does this have to do with women’s rights, you may ask? A lot, as it turns out. The great challenge of the 21st century is to build societies that can cope with the flock of black swans that are headed our way. Advancing and securing women’s rights, especially reproductive rights, is central to meeting that challenge.

Continue reading on RH Reality Check.

Laurie Mazur is the editor of A Pivotal Moment: Population, Justice & the Environmental Challenge, which received a Global Media Award from the Population Institute in 2010.

Sources: Munich Re.

Photo Credut: “Cygnus atratus (Black Swan),” courtesy flickr user Arthur Chapman. -

International River Basins: Mapping Institutional Resilience to Climate Change

›Institutions that manage river basins must assess their ability to deal with variable water supplies now, said Professor Aaron Wolf of Oregon State University at the July 28 ECSP event, “International River Basins: Mapping Institutional Resilience to Change.” “A lot of the world currently can’t deal with the variability that they have today, and we see climate change as an exacerbation to an already bad situation.”

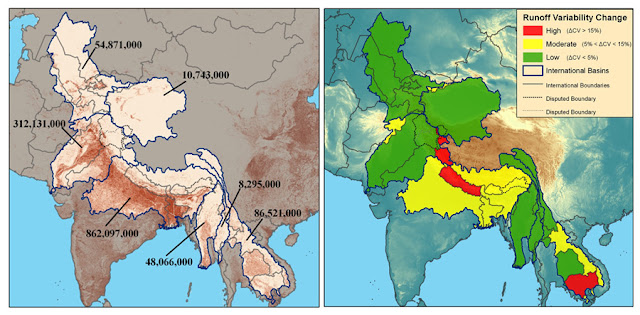

Wolf and his colleagues, Jim Duncan of the World Bank and Matt Zentner of the U.S. Department of Defense, discussed their efforts to map basins at risk for future tensions over water, as identified in their coauthored World Bank report, “Mapping the Resilience of International River Basins to Future Climate Change-Induced Water Variability.” [Video Below]

Floating Past the Rhetoric of “Water Wars”

Currently, there are 276 transnational water basins that cross the boundaries of two or more countries, said Wolf. “Forty percent of the world’s population lives within these waters, and interestingly, 80 percent of the world’s fresh water originates in basins that go through more than one country,” he said. Some of these boundaries are not particularly friendly – those along the Jordan and Indus Rivers, for example – but “to manage the water efficiently, we need to do it cooperatively,” he said.

Wolf and his colleagues found that most of the rhetoric about “water wars” was merely anecdotal, so they systematically documented how countries sharing river basins actually interact in their Basins at Risk project. The findings were surprising and counterintuitive: “Regularly we see that at any scale, two-thirds of the time we do anything over water, it is cooperative,” and actual violent conflict is extremely rare, said Wolf.

Additionally, the regions where they expected to see the most conflict – such as arid areas – were surprisingly the most cooperative. “Aridity leads to institutions to help manage aridity,” Wolf said. “You don’t need cooperation in a humid climate.”

“It’s not just about change in a basin, it’s about the relationship between change and the institutions that are developed to mitigate the impacts of change,” said Wolf. “The likelihood of conflict goes up when the rate of change in a basin exceeds the institutional capacity to absorb the change.”

Expanding the Database for Risk Assessment

Oregon State University’s Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) tracks tabular and spatial information on more than 680 freshwater treaties along 276 transboundary river basins, said Jim Duncan. The team expanded the database to include recent findings on variability, as well as the impacts of climate change on the future variability of those basins. “We have a lot more information that we are able to work with now,” Duncan said.

Analyzing the institutional vulnerability of treaties along with hydrological hazards, they found the risk of tension concentrated in African basins: The Niger, Congo, and Lake Chad basins “popped out,” said Duncan. When predicting future challenges, they found that basins in other areas, such as Southeastern Asia and Central Europe, would also be at risk.

Duncan and his colleagues were able to identify very nuanced deficiencies in institutional resilience. “Over half of the treaties that have ever been signed deal with variability only in terms of flood control, and we’re only seeing about 15 percent that deal with dry season control,” said Duncan. “It’s not the actual variability, but the magnitude of departure from what they’re experiencing now that is going to be really critical.”

Beyond Scarcity

“Generally speaking, it’s not really the water so much that people are willing to fight over, but it’s the issues associated with water that cause people to have disagreements,” said Matt Zentner. Water issues are not high on the national security agendas of most governments; they only link water to national security when it actively affects other sectors of society, such as economic growth, food availability, and electric power, he said. Agricultural production – the world’s largest consumer of water – will be a major concern for governments in the future, he said, especially in developing countries economically dependent on farming.

Some experts think that current international treaties are not enough, said Zentner. Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute has said that “the existing agreements and international principles for sharing water will not adequately handle the strain of future pressures, particularly those caused by climate change.”

How transboundary water treaties fare as the climate and consumption rates change is not as simple as measuring flow; the strength of governing institutions, the parties involved, and other variables all play major roles as well, said Zentner. “When you have flexibility built within [a treaty], it allows it to be a living, breathing, and important part of solving those [water] problems.”

Download the full event transcript here.

Sources: Oregon State University, Pacific Institute.

Photo Credit: “Confluence of the Zanskar and Indus,” courtesy of Flickr user Sanish Suresh. -

Watch: Aaron Wolf on the Himalayan and Other Transboundary Water Basins, Climate Change, and Institutional Resilience

›When Aaron Wolf, professor in the Department of Geoscience at Oregon State University, and his colleagues first looked at the dynamics behind water conflict in their Basins at Risk study, they found that a lot of the issues they’d assumed would lead to conflict, like scarcity or economic growth, didn’t necessarily. Instead they found that “there is a relationship between change in a [water] basin and the institutional capacity to absorb that change,” said Wolf in this interview with ECSP. “The change can be hydrologic: you’ve got floods, droughts, agricultural production growing…or institutions also change: countries kind of disintegrate, or there are new nations along basins.”

However, these changes happen independently. “Whether there is going to be conflict or not depends in a large part to what kind of institutions there are to help mitigate for the impacts of that change,” explained Wolf.

“If you have a drought or economic boom within a basin and you have two friendly countries with a long history of treaties and working together, the likelihood of that spiraling into conflict is fairly low. On the other hand, the same droughts or same economic growth between two countries that don’t have treaties, or there is hostility or concern about the motives of the other, that then could lead to settings that are more conflictive.”

Wolf stressed the importance of understanding hydrologic variability in relation to existing treaties around the world. After carefully examining hundreds of treaties, he and his colleagues created a way of measuring their variability to try to find potential hotspots.

“We know how variable basins are around the world; we know how well treaties can deal with variability. You put them together and you have some areas of concern: You may want to look a little closely to see what is happening as people try to mitigate these impacts,” said Wolf.

“We know that one of the overwhelming impacts of climate change is that the world is going to get more variable: Highs are going to be higher, and lows are going to be lower,” Wolf said.

Wolf used the Himalayan basins to illustrate the importance of overseeing the potential effects of climate change and institutional capacity. “There are a billion and half people who rely on the waters that originate in the Himalayas,” he pointed out. Because of climate change, the Himalayas may experience tremendous flooding, and conversely, extreme drought.

Unfortunately, Wolf said, “the Himalayan basins…do not have any treaty coverage to deal with that variability.” Without treaties, it is difficult for countries to cooperate and setup a framework for mitigating the variability that might arise. -

Backdraft: Minimizing Conflict in Climate Change Responses

›

“What are the conflicts or risks associated with response to climate change?” asked ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko at the Wilson Center on July 18. “How we respond to climate change may or may not contribute to conflict,” he said, but “at the end of the day, we need to do no harm.”