Showing posts from category *Blog Columns.

-

Local Case Studies of Population-Environment Connections

›“The role of intergenerational transfers, land, and education in fertility transition in rural Kenya: the case of Nyeri district” in Population & Environment by Karina M. Shreffler and F. Nii-Amoo Dodoo, explores the reasons for a dramatic and unexpected decline in fertility in rural Kenya. In one province, total fertility rate (TFR) declined from 8.4 to 3.7, from 1978 to 1998. The study found numerous contributing factors for this decline, which occurred more quickly and earlier than demographers expected, but land productivity seemed to be the primary motivator. A growing population and the tradition of dividing family land among sons made continuing to have large families unrealistic for these Kenyan families. “Family planning is, therefore, not the primary causal explanation for limiting the number of children, but rather serves to help families attain their ideal family sizes,” the authors conclude. Also in Population & Environment, “Impacts of population change on vulnerability and the capacity to adapt to climate change and variability: a typology based on lessons from ‘a hard country,’” by Robert McLeman, explores the potential for human communities to adapt to climate change. The article centers on a region in Ontario that is experiencing changes in both local climatic conditions and demographics. The study finds that demographic change can have both an adverse and positive effect on the ability of a community to successfully adapt to climate change and highlights the importance of social networks and social capital to a community’s resilience or vulnerability. McLeman also presents a new typology that he hopes will “serve the purpose of drawing greater attention to the degree to which adaptive capacity is responsive to population and demographic change.”

Also in Population & Environment, “Impacts of population change on vulnerability and the capacity to adapt to climate change and variability: a typology based on lessons from ‘a hard country,’” by Robert McLeman, explores the potential for human communities to adapt to climate change. The article centers on a region in Ontario that is experiencing changes in both local climatic conditions and demographics. The study finds that demographic change can have both an adverse and positive effect on the ability of a community to successfully adapt to climate change and highlights the importance of social networks and social capital to a community’s resilience or vulnerability. McLeman also presents a new typology that he hopes will “serve the purpose of drawing greater attention to the degree to which adaptive capacity is responsive to population and demographic change.”

SpringerLink offers free access to both these articles through August 15. -

‘Dialogue Television’ Interviews Paul Collier

›Watch below or on MHz Worldview

According to last week’s guest on Dialogue, restoring environmental order and eradicating global poverty have become the two defining challenges of our era. The environmental horror unfolding in the Gulf of Mexico illustrates just how difficult it is to balance economic progress and protection of the planet. It provides an alarming example of how the search for resources and profit can lead to the plunder of nature. Host John Milewski speaks with Oxford University economist Paul Collier on his latest book, The Plundered Planet: Why We Must and How We Can Manage Nature for Global Prosperity. Scheduled for broadcast starting June 30th, 2010 on MHz Worldview channel.

Paul Collier is professor of economics and director of the Center for the Study of African Economies at Oxford University. Formerly, he served as director of development research at the World Bank. He is the author of several books, including the award-winning The Bottom Billion.

Note: A QuickTime plug-in may be required to launch the video. -

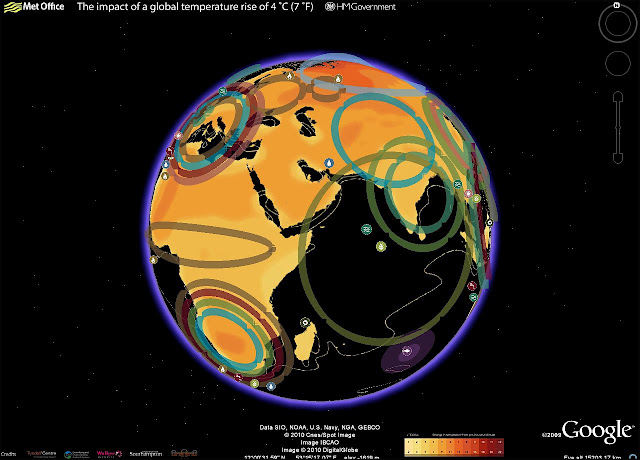

Rear Admiral Morisetti Launches the UK’s “4 Degree Map” on Google Earth

›Having had such success with the original “4 Degree Map” that the United Kingdom launched last October, my colleagues in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office have been working on a Google Earth version, which users can now download from the Foreign Office website.

This interactive map shows some of the possible impacts of a global temperature rise of 4 degrees Celsius (7° F). It underlines why the UK government and other countries believe we must keep global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial times; beyond that, the impacts will be increasingly disruptive to our global prosperity and security.

In my role as the UK’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy I have spoken to many colleagues in the international defense and security community about the threat climate change poses to our security. We need to understand how the impacts, as described in this map, will interact with other drivers of instability and global trends. Once we have this understanding we can then plan what needs to be done to mitigate the risks.

The map includes videos from the contributing scientists, who are led by the Met Office Hadley Centre. For example, if you click on the impact icon showing an increase in extreme weather events in the Gulf of Mexico region, up pops a video clip of the contributing scientist Dr Joanne Camp, talking about her research. It also includes examples of what the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and British Council are doing to increase people’s awareness of the risks climate change poses to our national security and prosperity, thus illustrating the FCO’s ongoing work on climate change and the low-carbon transition.

Rear Admiral Neil Morisetti is the United Kingdom’s Climate and Energy Security Envoy. -

New Film Looks at Sub-Saharan Africa’s Unmet Need for Family Planning

›A new documentary film released recently by Population Action International brings attention to the plight of women across sub-Saharan Africa who lack access to basic reproductive health supplies, such as condoms and contraceptives. Funded with the support of the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition, “Empty Handed” documents the unmet need for family planning services in the region, which has some of the world’s highest fertility rates.

PAI filmmaker Nathan Golon shot the film in Uganda earlier this year. The film’s focus on Ugandan women’s struggles in particular is with good reason, as the country has a well-documented history of providing insufficient family planning services. According to the CIA’s World Factbook, Uganda has the world’s second highest total fertility rate at 6.73 children per woman.

“Empty Handed” examines how a lack of family planning tools and services can lead to a slippery slope of unintended consequences, from unplanned pregnancies to the rampant spread of sexually transmitted diseases. The film revolves around interviews conducted with women who share common hardships as they try to access family planning from under-resourced local healthcare clinics, often traveling long distances only to find upon arrival that no contraceptives or condoms are available.

In addition to identifying past and current issues with reproductive healthcare access in sub-Saharan Africa, “Empty Handed” also puts forward some ideas for better meeting family planning needs of the more than 200 million women throughout the world without access to even basic contraception.

To watch the full film online, visit the “Empty Handed” website.

Sources: C.I.A., FHI, Population Action International, Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition -

Rough Waters Ahead: Our Changing Ocean

›From the ocean-themed June issue of Science comes “Sea-Level Rise and Its Impact on Coastal Zones“, by Robert J. Nicholls and Anny Cazenave. While sea-level rise will “almost certainly accelerate through the 21st century and beyond because of global warming,” Nicholls and Cazenave state that its magnitude remains uncertain. Small islands as well as the coasts of Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and China are identified as vulnerable areas because of their “dense populations, low elevations, appreciable rates of subsidence, and/or inadequate adaptive capacity.” Nicholls and Cazenave call for more research and analysis into adaptation, which “remains a major uncertainty.” “Ocean Acidification: Unprecedented, Unsettling,” by Richard A. Kerr, also appears in the June issue of Science. “Humans are caught up in a grand planetary experiment of lowering the ocean’s pH, with a potentially devastating toll on marine life,” begins Kerr, who aims to convince climate change-focused readers to also look at the world’s oceans. Rising pH levels, caused by ocean waters absorbing higher levels of carbon dioxide, are damaging shelled creatures, coral, and the organisms that rely on them for sustenance (which includes people, especially coastal populations dependent on the oceans for protein). An Australian survey recently found that calcification in the Great Barrier Reef had declined 14.2 percent since 1990 – a severe decline that has not been matched in the last 400 years. Kerr claims that “aside from the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact, the world has probably never seen the likes of what’s brewing in today’s oceans.”

“Ocean Acidification: Unprecedented, Unsettling,” by Richard A. Kerr, also appears in the June issue of Science. “Humans are caught up in a grand planetary experiment of lowering the ocean’s pH, with a potentially devastating toll on marine life,” begins Kerr, who aims to convince climate change-focused readers to also look at the world’s oceans. Rising pH levels, caused by ocean waters absorbing higher levels of carbon dioxide, are damaging shelled creatures, coral, and the organisms that rely on them for sustenance (which includes people, especially coastal populations dependent on the oceans for protein). An Australian survey recently found that calcification in the Great Barrier Reef had declined 14.2 percent since 1990 – a severe decline that has not been matched in the last 400 years. Kerr claims that “aside from the dinosaur-killing asteroid impact, the world has probably never seen the likes of what’s brewing in today’s oceans.” -

Top 10 Posts for June 2010

›Women Deliver and conflict minerals top the Beat this month:

1. Dot Mom: Women Deliver in Climate Change Debate

2. Copper in Afghanistan: Chinese Investments in Aynak

3. Rare Earth: A New Roadblock for Sustainable Energy?

4. Guest Contributor Caitlyn L Antrim, Rule of Law Committee for the Oceans: Trillions of Dollars of Minerals? Misuing Geology and Economics to the Detriment of Policy

5. Guest Contributor Michael Kugelman, Wilson Center: Look Beyond Islamabad To Solve Pakistan’s “Other” Threats

6. Afghanistan’s Mineral Wealth: Gold Mine, Curse, or Illusion?

7. Backdraft: The Conflict Potential of Climate Mitigation

8. VIDEO: Peter Gleick on Peak Water

9. The Plundered Planet: A Discussion With Paul Collier

10. Eye on Environmental Security: Natural Resource Frontiers at Sea -

U.S. Navy Task Force on Implications of Climate Change

›What about climate change will impact us? That’s the question the Navy’s Task Force Climate Change is trying to answer. Rear Admiral David Titley explains the task force’s objectives in this interview by the American Geophysical Union (AGU) at their recent “Climate Change and National Security” event on the Hill.

The task force is part of the military’s recent efforts to try to better understand what climate change will mean for the armed forces, from rising sea levels and ocean acidification to changing precipitation patterns. In the interview, Admiral Titley points out that for the Navy in particular, it is important to understand and anticipate what changes may occur since so many affect the maritime environment.

The Navy’s biggest near-term concern is the Arctic, where Admiral Titley says they expect to face significant periods of almost completely open ocean during the next two to three decades. “That has huge implications,” says Titley, “since as we all know the Arctic is in fact an ocean and we are the United States Navy. So that will be an ocean that we will be called upon to be present in that right now we’re not.”

Longer term, the admiral points to resource scarcity and access issues and sea level rise (potentially 1-2 meters) as the most important contributing factors to instability, particularly in places like Asia, where even small changes can have huge impacts on the stability of certain countries. The sum of these parts plus population growth, an intersection we examine here at The New Security Beat, is something that deserves more attention, according to Titley. “The combination of climate, water, demographics, natural resources – the interplay of all those – I think needs to be looked at,” he says.

Check out the AGU site for more information, including an interview with Jeffrey Mazo – whose book Climate Conflict we recently reviewed – discussing climate change winners and losers and the developing world (hint: the developing world are the losers).

Sources: American Geophysical Union, New York Times.

Video Credit: “What does Climate Change mean for the US Navy?” courtesy of YouTube user AGUvideos. -

U.S.-Mexico Cooperation on Renewable Energy: Building a Green Agenda

›Could joint green-energy development help improve relations between the United States and Mexico? Speakers at this spring’s launch of “Environment, Development and Growth: U.S.-Mexico Cooperation in Renewable Energies,” a report released by the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute, agreed that cooperating on renewable energy is a positive step. However, the panelists asserted that cooperation could be maximized by better harnessing Mexico’s renewable resources and by leveraging the economic complementarities that exist among the border states.

Mexico’s Green Energy Potential

Mexico has large untapped areas of geothermal, wind, and solar potential, according to Duncan Wood, author of the Wilson Center report and chair of the Department of International Relations at the Instituto Tecnologico Autonomo de Mexico (ITAM). Already, the country is the world’s third-largest producer of geothermal energy, and has large geothermal deposits in Baja California near major U.S. markets, such as San Diego and Los Angeles.

Mexico also offers great promise in wind power, with an estimated potential output of 1,800 to 2,400 megawatts for Baja California and 5,000 megawatts for southern Oaxaca state. Though Oaxaca is far from the U.S. border, it will soon be able to export electricity to U.S. markets, once Mexico’s mainland electrical grid is connected to the United States.

Wood also pointed out that Mexico is rich in solar energy, which could be marketed to the United States—particularly from the Baja California peninsula, which is the only part of the Mexican grid currently connected the United States. In biomass, he added, little investment has been made so far.

Opening New Avenues for Collaboration

With Mexico’s oil fields experiencing long-term and, in some cases, precipitous declines, the country is plotting a “future as a green nation,” shifting its policy focus toward alternative energy development, said Wood. In addition, Mexico’s renewable sector does have not the blanket prohibitions on private ventures that exist in the hydrocarbons sector, and regulatory adjustments over the past few administrations have enabled a more robust private stake in electricity generation and transmission.

A U.S.-Mexico taskforce on renewables was recently formed—an announcement timed to coincide with President Felipe Calderon’s April 2010 state visit to Washington—and there has been high-level engagement on the issue by both administrations. Collaboration between Mexico and U.S. government agencies through the Mexico Renewable Energy Program has enabled richer development of Mexico’s renewable resources while promoting the electrification and economic development of parts of rural Mexico. Joe Dukert, an independent energy analyst affiliated with the Center for Strategic & International Studies, pointed out that U.S.-Mexico collaboration on renewables is a little-acknowledged area of bilateral cooperation, and stressed the economic complementarities that exist between the two countries on the issue. He noted, for example, that Mexico was well-positioned to furnish power to help California meet its Renewables Portfolio Standard (RPS) by 2020.

Joe Dukert, an independent energy analyst affiliated with the Center for Strategic & International Studies, pointed out that U.S.-Mexico collaboration on renewables is a little-acknowledged area of bilateral cooperation, and stressed the economic complementarities that exist between the two countries on the issue. He noted, for example, that Mexico was well-positioned to furnish power to help California meet its Renewables Portfolio Standard (RPS) by 2020.

“Mexico can help them reach these [renewable energy] targets,” Dukert said. Yet at the same time, he said that Mexico needs to do more to enhance its profile as a renewable-energy supplier, and specifically suggested that energy attaches be assigned to the embassy and consulates.

Johanna Mendelson Forman, a senior associate with the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, emphasized the linkages connecting climate change, energy, and economic development. Forman warned that Mexico’s inadequate energy stocks are a problem for the United States, adding that “energy poverty is a real issue in Mexico.” Energy development and climate change—which are perceived as less polemical than other issues—are good entry points for a broader U.S.-Mexico dialogue, she remarked.

Robert Donnelly is a program associate with the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: “Wind Mill Farm (Mexico),” courtesy of flickr user Cedric’s pics. Speaker photos by David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center.