Showing posts from category agriculture.

-

Weekly Reading

›A study in Science warns that climate change “is likely to have more dramatic effects on global agriculture than previously predicted, leaving around half the world’s population facing serious food shortages,” reports SciDev.Net.

In an op-ed for Defense News, Sherri Goodman and David Catarious express hope that President-Elect Barack Obama will take steps to reduce climate change’s security impacts.

“Much of politics is repetitive and unproductive, but sometimes a logjam breaks. In the past two years, most politicians have ceased being in denial about climate change, greenhouse emissions, limits to water, and peak oil. All these crises reflect the deeper underlying problem: our population growth is out of control. Waiting for the population debate to begin is like waiting for the other shoe to drop,” writes Mark O’Connor for the Sydney Morning Herald.

Regional Water Cooperation and Peacebuilding in the Middle East, an Initiative for Peacebuilding paper by Annika Kramer of Adelphi Research, surveys peacebuilding challenges and opportunities around water among Israelis, Palestinians, and Jordanians.

Stephan Faris outlines the global divisions over climate change policy on Global Post, a new online-only international media site. -

Weekly Reading

›“Climate change of that scale [a 5° C increase] will cause enormous resource wars, over water, arable land, and massive population displacements. We’re not talking about ten thousand people. We’re not talking about ten million people, we’re talking about hundreds of millions to billions of people being flooded out, permanently,” said Steven Chu, President-elect Barack Obama’s choice for secretary of energy, at the National Clean Energy Summit this summer.

“As the world focuses on the outcomes of the meeting on climate change that just concluded in Poznan, Poland, I am sitting in a workshop in Nazret, Ethiopia, listening to a panel of farmers talking about the effects of climate change on their lives – less rain, lower crop yields, malaria, no milk for their children,” writes Karen Hardee on Population Action International’s blog. “They are acutely aware that farm sizes shrink with each generation and speak eloquently of the need for access to family planning so they can have fewer children.”

The New York Times reports on the fight for control over uranium deposits in northern Niger, part of its ongoing series on resource conflict.

The current volume of Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations examines global water governance.

On the Carnegie Council’s “Policy Innovations” website, Rebecca Laks reports on efforts to incorporate alternative fuels into refugee camps in order to reduce deforestation in the surrounding environment.

The Center for American Progress has released “Putting Aid and Trade to Work: Fostering Development for Sustainable Security,” along with related documents.

The Sabaot Land Defence Force and the Kenyan army have been fighting over the rights to land in western Kenya for years, and local women are suffering, reports IRIN News. Fighters from both sides often rape women, giving them HIV/AIDS.

“Cleaning the environment has been identified as major tool in waging war against mosquitoes” and malaria in Nigeria, reports the Vanguard. -

Weekly Reading

›The Center for Global Development’s interactive 2008 Commitment to Development Index rates 22 wealthy countries on how much they help poor countries in seven areas: aid, trade, investment, migration, environment, security, and technology.

“Destitution, distortion and deforestation: The impact of conflict on the timber and woodfuel trade in Darfur,” a new report from the UN Environment Programme’s Post-Conflict and Disaster Management Branch, says that saw-mills and wood-fired brick kilns are devastating Darfur’s fragile environment.

“If we are successful in reaching peak population sooner, at a lower number of people, rather than later with more people, we will be much more able to confront the myriad interlocking crises we face — a comparatively less crowded planet is an easier planet on which to build a bright green future,” writes Worldchanging’s Alex Steffen.

“In the case of the South American farms studied in this report, average simulated revenue losses from climate change in 2100 are estimated to range from 12 percent for a mild climate change scenario to 50 percent in a more severe scenario, even after farmers undertake adaptive reactions to minimize the damage,” finds a World Bank report on climate change and Latin America. Foreign Policy’s Passport blog comments.

In A Framework for Achieving Energy Security and Arresting Global Warming, Ken Berlin of the Center for American Progress sets out five sets of issues the federal government will have to address in order to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on foreign oil.

“Ask any environmental organisation what it thinks about birth control; it’ll sidestep the issue, and say it’s not their place to comment. If a commentator says there are too many people on the planet, their words smack of authoritarian dictatorships and human rights violations, and echo traces of unpalatable eugenics. However, the reality is that every time we eat, switch on a light, get in a car, drink a beer, go on holiday or buy something to wear or use, we are adding to our environmental footprint,” writes Joanna Benn in BBC’s Green Room, in an article that generated a lively stream of commentary.

Land Conflicts: A practical guide to dealing with land disputes, a report by GTZ, is available online. -

Food Production Goes Global, Sparking Land Grabs in Developing World

›December 8, 2008 // By Will Rogers As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

From the Persian Gulf to East Asia, governments and international companies alike have been lobbying developing countries in Africa and Asia to produce grain for food and alternative energy. The Guardian reported on November 22nd that Qatar recently leased 40,000 hectares of Kenyan farmland in return for funding a £2.4 billion port on the island of Lamu, a popular tourist site just off the Kenyan coast. The Saudi Binladen Group is said to be finalizing a deal with Indonesia to lease land for basmati rice production, while other Arab investors, including the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, have bought land rights for agricultural production in Sudan and Pakistan. Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has been “courting would-be Saudi investors,” despite his country’s own deplorable food insecurity and chronic malnutrition.

Meanwhile, the Telegraph reported that South Korea’s Daewoo Logistics has been working to secure a 99-year lease for 3.2 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar that it will use to “grow 5 million metric tons of maize a year and 500,000 tons of palm oil” to use as biofuel in South Korea. The company says it expects to pay almost nothing besides infrastructure costs and employment training in return for its use of the land. Despite Madagascar’s rapid population growth and pervasive food insecurity, the deal, if signed, will allow the South Korean company to lease approximately half of the current arable farmland on the island state.

In an effort to combat a freshwater shortage, China has secured an agreement with Laos for a 50-year lease of 1,600 hectares of land in return for funding a new sports complex in Vientiane for the 2009 Southeast Asian Games. And with only 8 percent of the world’s arable land and more than one-fifth of the world’s population to feed, China continues to encourage its businesses to go outside China to produce food, looking to developing countries in Africa and Latin America.

Jacques Diouf, director-general of the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, recently warned that these deals are a “political hot potato” that could prove devastating to the developing world’s own food supply, as several of these states already face severe food insecurity. Diouf has expressed concern that these deals could breed a “neo-colonial” agricultural system that would have the world’s poorest and most malnourished feeding the rich at their own expense.

And with land rights a contentious issue throughout the developing world—including in Haiti, Kenya, and Sudan, for instance—these agreements could spark civil conflict if governments and foreign investors fail to strike equitable deals that also benefit local populations. “Land is an extremely sensitive thing,” warns Steve Wiggins, a rural development expert at the Overseas Development Institute. “This could go horribly wrong if you don’t learn the lessons of history” and attempt to minimize inequality.

As food prices continue to climb, more and more countries are likely to scramble to gain access to the developing world’s arable land. Without land-use agreements that ensure a host country’s domestic food supply is secure before its foreign investor’s, long-term sustainable development could be set back decades, something impoverished developing countries simply cannot afford.

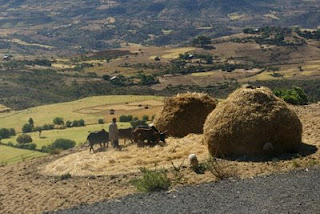

Photo: A man threshing in Ethiopia. Long plagued by acute food insecurity, Ethiopia’s arable land is sought by more-developed countries to ensure the stability of their own food stocks. Courtesy of Flickr user Eileen Delhi. -

Weekly Reading

›Military leaders and climate experts gathered in Paris for a November 3-5 conference on the role of the military in combating climate change. A conference report will include “proven strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while improving military effectiveness.”

The 2008 Africa Population Data Sheet, a joint project of the Population Reference Bureau and the African Population and Health Research Center, reveals significant differences between northern and sub-Saharan Africa. Also from PRB, “Reproductive Health in Sub-Saharan Africa” examines family planning use, family size, maternal mortality, and HIV/AIDS in major subregions of sub-Saharan Africa.

In the October 2008 issue of Humanitarian Exchange Magazine, Alexander Tyler of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees for Somalia argues that longer-term livelihoods projects must be incorporated into emergency humanitarian relief efforts. The authors of the Center for American Progress report The Cost of Reaction: The Long-Term Costs of Short-Term Cures (reviewed on the New Security Beat) would likely agree; they argue that although emergency aid is necessary, “what is true in our own lives is true on the international stage—an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The Dining & Wine section of the New York Times profiles a Quichua community in the Ecuadorian Amazon that has formed a successful chocolate cooperative with the help of a volunteer for a biodiversity foundation. “They wanted to find a way to survive and thrive as they faced pressure from companies that sought to log their hardwood trees, drill on their land for oil and mine for gold,” reports the Times. -

United Nations Observes International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict

›November 6, 2008 // By Rachel Weisshaar Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“impairs ecosystems and natural resources long beyond beyond the period of conflict, and often extends beyond the limits of national territories and the present generation.”

Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“impairs ecosystems and natural resources long beyond beyond the period of conflict, and often extends beyond the limits of national territories and the present generation.”

In a written statement issued today, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon points out that although natural resources are often exploited during war, they are also essential to establishing peace:The environment and natural resources are crucial in consolidating peace within and between war-torn societies. Several countries in the Great Lakes Region of Africa established trans-boundary cooperation to manage their shared natural resources. Lasting peace in Darfur will depend in part on resolving the underlying competition for water and fertile land. And there can be no durable peace in Afghanistan if the natural resources that sustain livelihoods and ecosystems are destroyed.

As the Development Gateway Foundation’s Environment and Development Community emphasizes, “[e]nvironmental security, both for reducing the threats of war, and in successfully rehabilitating a country following conflict, must no longer be viewed as a luxury but needs to be seen as a fundamental part of a long lasting peace policy.”

Some of the United Nations’ most important contributions to illuminating the links between conflict and environmental degradation are the excellent post-conflict environmental assessments that the UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) Disasters and Conflicts Programme has carried out in Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Sudan, among other countries. UNEP is currently preparing to conduct an assessment of Rwanda’s environment.

Photo: A Kuwaiti oil field set afire by retreating Iraqi troops burns in the distance beyond an abandoned Iraqi tank following Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of Flickr user Leitmotiv. -

Prostitution, Agriculture, Development Fuel Human Trafficking in Brazil

›October 28, 2008 // By Ana Janaina NelsonModern-day slavery, also known as human trafficking, is the third most lucrative form of organized crime in the world, after trade in illegal drugs and arms trafficking. Today, 27 million people are enslaved—mostly as a result of debt bondage. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report Trafficking in Persons: Global Patterns found that Brazil is the third-largest source of human trafficking in the Western hemisphere, after Mexico and Colombia. According to the U.S. Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, 250,000-500,000 Brazilian children are currently exploited for prostitution, both domestically and abroad. NGOs estimate that 75,000 Brazilian women and girls—most of them trafficked—work as prostitutes in neighboring South American countries, the United States, and Europe.

In addition, notes the Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, 25,000-100,000 Brazilian men are forced into domestic slave labor. “Approximately half of the nearly 6,000 men freed from slave labor in 2007 were found exploited on plantations growing sugar cane for the production of ethanol, a growing trend,” says the report. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the “agricultural states of the north, like Piaui, Maranhao, Pará and Mato Grosso, are the most problematic.” Agriculture and development have also been linked to sex trafficking. A 2003 study by the Brazilian NGO CECRIA found that in the Amazon, sexual exploitation of children often occurs in brothels that cater to mining settlements. The study also highlighted the prevalence of sex trafficking in regions with major development projects.

In response to growing awareness of the magnitude of this problem, the Brazilian Ministry of Justice has stepped up its efforts to combat human trafficking, adopting the ILO and UNODC’s “three-P” approach: prevention, prosecution, and protection. Prevention measures in Brazil focus on sexual exploitation, the most common type of forced labor for trafficked Brazilians. These measures include educating vulnerable populations about avoiding human trafficking, as well as drawing tourists’ attention to criminal penalties under Brazilian law for patronizing prostitutes.

Prosecution efforts in Brazil are also improving: In 2004, Brazil ratified the Palermo Protocol (pdf), the main international legal instrument for combating human trafficking. A year later, the country adopted a National Plan to Combat Human Trafficking, which aims to train those responsible for prosecuting traffickers and protecting victims—primarily police and judges. In addition, notes the Trafficking in Persons Report 2008:The Ministry of Labor’s anti-slave labor mobile units increased their operations during the year, as the unit’s labor inspectors freed victims, forced those responsible for forced labor to pay often substantial amounts in fines and restitution to the victims, and then moved on to others locations to inspect. Mobile unit inspectors did not, however, seize evidence or attempt to interview witnesses with the goal of developing a criminal investigation or prosecution because inspectors and the labor court prosecutors who accompany them have only civil jurisdiction. Because their exploiters are rarely punished, many of the rescued victims are ultimately re-trafficked.

The U.S. Department of State established a four-tiered assessment system to rate countries’ compliance with international trafficking mandates. In 2006, Brazil was listed on the Tier 2 Special Watch List, the second-worst rating, despite recognition that the government made “significant efforts” to combat human trafficking. Brazil recently moved into the Tier 2 category, however, due to more concerted interagency efforts, as well as greater compliance with international guidelines. Yet one wonders whether Brazil will be able to achieve Tier 1 status any time soon, given the Brazilian government’s focus on biofuel- and agriculture-fueled economic growth and the fact that the global financial crisis is likely to drive people into increasingly desperate economic straits.

By Brazil Institute Intern Ana Janaina Nelson.

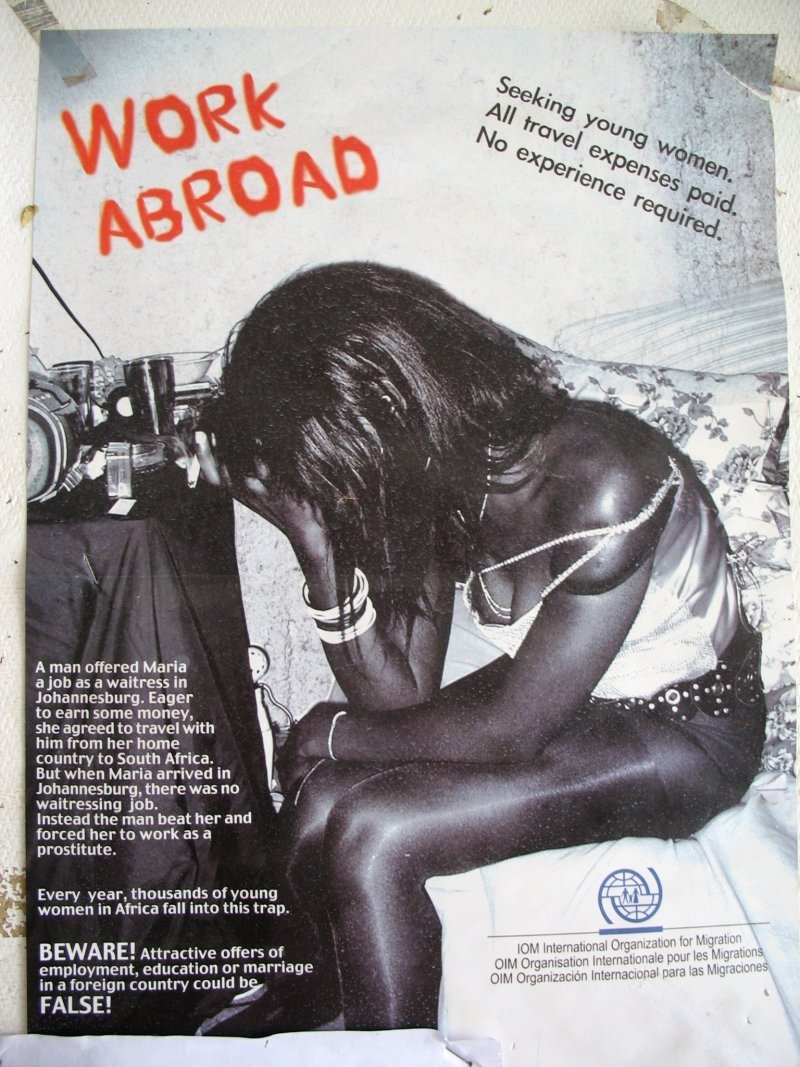

Photo: A poster warns African women of the dangers of human trafficking; Brazilian women are subject to similar dangers. Courtesy of Flickr user mvcorks. -

A Roadmap for Future U.S. International Water Policy

› When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have more than 15 government agencies with capacities to address water and sanitation issues abroad. And yes, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development published a joint strategic framework this year for action on water issues in the developing world.

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have more than 15 government agencies with capacities to address water and sanitation issues abroad. And yes, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development published a joint strategic framework this year for action on water issues in the developing world.

However, the U.S. government (USG) does not yet have an overarching strategy to guide our water programs abroad and maximize synergies among (and within) agencies. Furthermore, the 2005 Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act—which calls for increased water and sanitation assistance to developing countries—has yet to be funded and implemented in a fashion that satisfies lawmakers. In fact, just last week, legislation was introduced in both the House and the Senate to enhance the capacity of the USG to fully implement the Water for the Poor Act.

Why has implementation been so slow? An underlying problem is that water still has no institutional home in the USG, unlike other resources like agriculture and energy, which have entire departments devoted to them. In the current system, interagency water coordination falls on a small, under-resourced (yet incredibly talented and dedicated) team in the State Department comprised of individuals who must juggle competing priorities under the broad portfolio of Oceans, Environment, and Science. In part, it is water’s institutional homelessness that hinders interagency collaboration, as mandates and funding for addressing water issues are not always clearly delineated.

So, what should be done? For the last year and a half, the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Global Strategy Institute has consulted with policy experts, advocates, scientists, and practitioners to answer this million-dollar question. In our report, Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy, we conclude that if we are serious about achieving a range of our strategic national interests, water must be elevated as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. Water is paramount to human health, agricultural and energy production, education, economic development, post-conflict stabilization, and more—therefore, our government’s organizational structure and the resources it commits to water should reflect the strategic importance of this resource.

Studies’ (CSIS) Global Strategy Institute has consulted with policy experts, advocates, scientists, and practitioners to answer this million-dollar question. In our report, Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy, we conclude that if we are serious about achieving a range of our strategic national interests, water must be elevated as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. Water is paramount to human health, agricultural and energy production, education, economic development, post-conflict stabilization, and more—therefore, our government’s organizational structure and the resources it commits to water should reflect the strategic importance of this resource.

We propose the creation of a new bureau or “one-stop shop” for water policy in the State Department to lead in strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation of international water programs; mobilize resources in support of water programming overseas; provide outreach to Congress and important stakeholders; and serve as a research and information clearinghouse. This would require significant support from the highest levels of government, increased funding, and greater collaboration with the private and independent sectors.

The current economic crisis means we are likely to face even greater competition for scarce foreign aid resources. But I would argue—paraphrasing Congressman Earl Blumenauer at our report rollout—that relatively little funding toward water and sanitation can have a significant impact around the world. As we tighten our belts during this period of financial instability, it is even more important that we invest in cross-cutting issues that yield the highest returns across defense, development, and diplomacy. Water is an excellent place to start.

Rachel Posner is a research associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Global Strategy Institute.

Photo: Environmental Change and Security Program Director Geoff Dabelko and Congressman Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) at the launch of Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy. Courtesy of CSIS.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world. Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“

Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have  Studies’ (CSIS)

Studies’ (CSIS)